No creoles?

« previous post | next post »

Damián Blasi, Susanne Michaelis and Martin Haspelmath, "Grammars are robustly transmitted even during the emergence of creole languages", Nature Human Behaviour 2017:

[W]e analyse 48 creole languages and 111 non-creole languages from all continents and conclude that the similarities (and differences) between creoles can be explained by genealogical and contact processes, as with non-creole languages, with the difference that creoles have more than one language in their ancestry. While a creole profile can be detected statistically, this stems from an over-representation of Western European and West African languages in their context of emergence. Our findings call into question the existence of a pidgin stage in creole development and of creole-specific innovations. In general, given their extreme conditions of emergence, they lend support to the idea that language learning and transmission are remarkably resilient processes.

Email from Damián Blasi puts it more bluntly:

The basic conclusions are that 1) creoles clearly continue the linguistic structure of the languages that preceded them, 2) we don't have any evidence for a pidgin stage preceding creoles and 3) no evidence for purely creole features (like SVO) whatsoever.

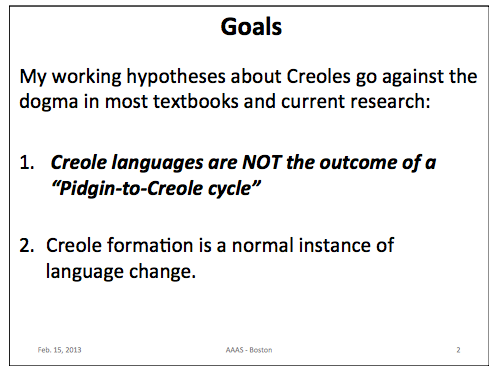

This is striking vindication of a position that Michel DeGraff has been arguing for many years. In "Ayiti Pare" 5/2/2013, I linked to the slides of his presentation in the AAAS 2013 symposium on Historical Syntax, "A Null Theory of Creole Formation", and quoted his abstract:

Creole languages have traditionally been excluded from the scope of the Comparative Method in historical linguistics. To date, the most persistent and popular theories of Creole formation claim that Creole languages constitute an exceptional “Creole typology” whose members lie outside well-established language-family trees. Furthermore Creole languages are often claimed as the least complex human languages. Another view takes Creoles as relexified versions of their substrates. Our ongoing work suggests that these claims are all mistaken. We’ve argued that Creoles duly fall in the scope of the Comparative Method as languages genealogically affiliated with their lexifiers. Here we offer the bases of a framework for a null theory of Creole formation, a theory that we believe is empirically more adequate than the popular exceptionalist claims. This null theory does away with any sui generis stipulation that applies to Creole languages only. Instead it is rooted in basic assumptions and findings about Universal Grammar—assumptions and findings that apply to all languages. In this approach, the creation of new languages, whether or not they are labeled “Creole,” sheds lights on the interplay of first- and second-language acquisition as new grammars are built from complex and variable input. The effects of this interplay are similar across familiar cases of Creole formation as in the creation of Haitian Creole and familiar cases of language change as in the history of French or English. Such null theory undermines various traditional claims about “Creole simplicity” and “Creole typology” whereby Creoles are considered exceptional languages of lowest complexity. This approach also makes for a better integration of Creole phenomena to our general understanding of the cognitive bases for language change.

Or, more succinctly and in larger type, the first slide from Michel's presentation:

See also Enoch Aboh and Michel DeGraff, "A Null Theory of Creole Formation Based on Universal Grammar", Oxford Handbook of Universal Grammar 2016.

One difference: DeGraff argues that "Creoles duly fall in the scope of the Comparative Method as languages genealogically affiliated with their lexifiers", whereas Blasi et al. suggest that "creoles can be explained by genealogical and contact processes, as with non-creole languages, with the difference that creoles have more than one language in their ancestry". My impression, from the outside of the discussion, is that this is a difference of emphasis.

It should go without saying that not everyone will agree with either position, and some will instead insist on the "pidgin stage" hypothesis.

mg said,

September 4, 2017 @ 4:38 pm

"creoles can be explained by genealogical and contact processes, as with non-creole languages, with the difference that creoles have more than one language in their ancestry"

Seems to me that describes English as the epitome of a creole that has just been around longer than the languages we currently refer to as creoles. Anyone trying to spell English words or conjugate verbs sees the vestiges of the various parent languages incorporated over centuries of conquest.

chris said,

September 4, 2017 @ 5:59 pm

@mg: Not just conquest, either — the Greeks never conquered England. The Romans did, but I don't think it's directly relevant to the presence of Latin-origin words in English (of course, the Roman Empire's geopolitical influence *in general* was largely responsible for its enduring cultural influence and use as a prestige language).

Are there any languages that actually have only one language in their ancestry? How do you distinguish between "ancestry" and "influence"? ISTM that the metaphor of languages having ancestors is seriously misleading; language lacks a genotype/phenotype division, so its "evolution" is promiscuously Lamarckian.

Andrew Usher said,

September 4, 2017 @ 7:04 pm

Well, at least he's going right ahead and admitting that he's starting with the conclusion (which, it's not hard to guess, is motivated by a certain political idea) and then fitting the data to it. And, yes, by his muddled kind of definition, English could be called a creole – but it isn't, because we can trace its grammatical evolution from Old English and see that it's not different in kind from the other Germanic languages.

His point that 'Creole formation is a normal instance of language change' is empty. Of course it's 'normal', since we observe it occurring in the real world. But lumping all forms of language change into a basket called 'normal' isn't useful, interesting, or scientific. A scientist should want to classify things further, and that's exactly what the traditional category of 'creole' does. Any theory of course could be wrong, but I won't be persuaded by someone obviously practising ideology and not science.

postageincluded said,

September 4, 2017 @ 7:47 pm

@Andrew Usher

Being just an interested layman I'd be interested in what you mean by "political" there. Could it be the mention of "Universal Grammar"?

David Marjanović said,

September 4, 2017 @ 8:09 pm

Slide 19 of DeGraff's presentation suddenly switches from the modern definition of "creole" (descendant of a pidgin) to an older one (language with vocabulary of mixed origin)! Of course English fits the older definition better than Haitian Creole does! That's part of why the newer definition was adopted in the first place, isn't it?

And why a is translated as "the" on slide 32 is beyond me. Southern German, too, has such a particle that means "in accordance with my hopes or sarcastic expectations".

The conclusion (slide 41) comes as a great surprise, seeing as the preceding 40 slides said nothing about "the interplay of first- and second-language acquisition" or "complex and variable input"; it should have been called "prospects for future research" or suchlike.

David Marjanović said,

September 4, 2017 @ 8:16 pm

I have institutional access to several Nature journals, so I'll find out tomorrow if that includes Nature Human Behaviour…

In the meantime, back to DeGraff's presentation: slide 21 (among others) aims to show that the grammar of Haitian Creole developed straight from the French one, but the TMA markers it starts with aren't TMA markers in French, they're lexical words with pretty different meanings that were radically reinterpreted and grammaticalized in Haitian Creole. AFAIK, that's rather rare in ordinary language evolution.

Andrew Usher said,

September 4, 2017 @ 10:02 pm

postageincluded:

Of course not, 'Universal Grammar' is a legitimate linguistic theory. The real political point is that he clearly sees the usual belief about creoles to be marking them as inferior languages or not real languages (a gross simplification at best), and of course wants to remedy that great injustice.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

David D ROBERTSON said,

September 4, 2017 @ 11:29 pm

Some creoles demonstrably have pidgin ancestors. Grand Ronde Reservation creole Chinuk Wawa. South Pacific English-based creoles. But yes, creoles need not develop from pidgins as far as the evidence shows. But no, pidgins can be presumed to possess all the characteristics of human language–whatever those characteristics may turn out to be.

Rubrick said,

September 4, 2017 @ 11:34 pm

I personally subscribe to the unorthodox theory that creoles, like comments sections, are actually formed by the interactions between straw men.

boynamedsue said,

September 5, 2017 @ 12:55 am

I don't think anyone in modern linguistics would describe Creoles as the "simplest languages". Their grammars are very efficient in terms of morphology, in that they communicate information about tense and aspect in very regular ways using markers, which means they are objectively easier to learn than highly inflected languages with different verb and noun types and tonnes of irregular forms. But "simple" isn't an adjective that can be usefully applied to a natural language, given they all seem to be capable of doing the same job where the speaker understands the concept they are attempting to communicate.

If no pidgin stage exists, then surely there can be no useful definition of what a Creole is? The debate about whether English is a creole would make no sense at all in this case, and the answer which is currently generally "no" would have to be changed to "sure, why not?". The languages we call creoles now tend to share certain features, grammaticalised markers, absence of nominal cases (except sometimes in number) and verbal complexity which for me must reflect not just an extent of language contact but something different occurring.

Jason said,

September 5, 2017 @ 1:03 am

I've been saying this for years. Bickerton's pidgen-creole pathway has to be considered thoroughly discredited at this stage. John McWhorter has been carving away at the foundations of the bioprogram hypothesis for years, for example showing substrate origins for all of Bickerton's allegedly bioprogrammatic features of Saramaccan without quite rejecting Bickerton in his entirety.

There are no pidgins in the Bickerton sense. We need a new theory of interlanguage to explain how languages change and alter under close, intensive cultural contact (or dominance) by another language. This needs to take into account such influences as code-shifting and L2 acquisition fossilization as major drivers in the evolution of new interlanguages with no intermediate "pidgin" stage.

Jason said,

September 5, 2017 @ 1:16 am

@boynamedsue

[i]I don't think anyone in modern linguistics would describe Creoles as the "

"simplest languages"[/i]

John McWhorter has been arguing precisely this, in, for example, "Language Interrupted" and his paper "The World's Simplest Languages are Creole Grammars". There's no need to equate "simple" with "simpleminded" or "inarticulate." The efficient morphology, extremely regular grammar etc. are precisely what makes them "simple" in the relevant sense.

As for the definition of creole, I submit the following: A creole is a fully functioning natural language that looks to its speakers of its lexifier/superstrate an awful lot like imperfectly acquired L2 interlanguage. This explains a lot of the enduring stigma these languages attract.

JPL said,

September 5, 2017 @ 1:49 am

I'm not able to comment further right now, but what about Thomason and Kaufman, Language Contact, Creolization and Genetic Linguistics, 1988, but basically worked out in 1975: "… the history of a language is a function of the history of its speakers, and not an independent phenomenon that can be thoroughly studied without reference to the social context in which it is embedded." Also, what about mixed languages, such as Michif, among other things?

boynamedsue said,

September 5, 2017 @ 2:24 am

@Jason

Thanks for the info! I'll read up on that. If McWhorter's literally saying "simplicity" I'd say the criticisms in the powerpoint are fair.

However, I wouldn't say that simplicity is required for creoles to be descended from pidgins, it is not sufficient to point to aspects of complexity in Haitian Creole and say "this can't be descended from a pidgin". Haitian has had an existence of at least 350 years since its pidgin stage, the creolization process itself would give rise to complexity, as would its subsequent evolution. It's particularly strange to say that pidgins have not been documented to evolve into creoles, what about Tok Piksin? The process has been documented in great detail.

ajay said,

September 5, 2017 @ 3:31 am

Southern German, too, has such a particle that means "in accordance with my hopes or sarcastic expectations".

What an absolutely terrific linguistic feature. Almost as good as the Sumerian (I think) character which signifies "the word which follows refers to a duck".

David said,

September 5, 2017 @ 5:14 am

Calling analytical languages "less complex" is a simplification. The fact is that a language must be used by a stable population for a long period of time to develop features like the super-synthetic nature of native american languages. Why? Because in synthetic grammars, the representation is even further abstracted from the represented. Word order can contain ordinal information in an iconic way that complex morphology can't. So it is only natural to use these methods to communicate between two speakers who don't share much of the same language.

David said,

September 5, 2017 @ 5:18 am

It's an information theory problem at that point. Yes, colonizers are oppressive and that is morally bad. But that doesn't make information travel any faster across a noisy channel of a given bandwidth.

John McWhorter said,

September 5, 2017 @ 5:34 am

This article vindicates nothing. The idea that grammatical continuities from the lexifier and the substrate disconfirm that creoles emerged from pidgins is inaccurate: pidgins often have plenty of substrate influence. The question is what kind, and this study leaves intact the claim that creoles are the product of a break in transmission. This by no means requires that this was a jelled, long-established pidgin variety like Chinook Jargon – the issue is transmission. The nut of the issue is this: as many commenters note, it is undeniable that some creoles, like Tok Pisin, emerged from pidgins. The DeGraffian idea is that we must suppose that this wasn't true of Haitian and other plantation creoles, despite that they differ from their source languages in the exact same way as Chinook Jargon creole, Tok Pisin, etc. have. However, there is no logical or empirical reason to suppose so, as I have argued in many articles now, and this Nature piece's argumentation is inapplicable to that of my work and that of others who agree with me. Beware also the grand old challenge that "no one has identified any exclusively creole features" – my point, at least, has been that creolization can create a diagnostic trio of ABSENCES (my Prototype proposal). One often reads that this has been refuted by counterexamples, but I have shown the error in all of those propositions in various sources (Soninke, Old Chinese, Mandarin, Magoua French), unacknowledged for almost 20 years now by those committed to the "no pidgin" idea. Quite simply, no one actually has presented a viable exception to the Prototype proposal, and anyone who supposes that my argumentation on the issue is circular will likely find that surmise disconfirmed upon consulting the relevant articles. The approach of this Nature piece simply does not, and cannot, address the finer-grained approach I have suggested in trying to characterize what a creole language is. I recommend my DEFINING CREOLE and LANGUAGE SIMPLICITY AND COMPLEXITY for basic argumentation on these points; stay tuned also for my upcoming monograph aimed precisely at linguists beyond creole studies under the impression that it has been somehow proven that "creoles don't come from pidgins." I understand the attraction of that claim, but it is empirically false.

Sally Thomason said,

September 5, 2017 @ 6:49 am

"[W]e analyse 48 creole languages and 111 non-creole languages from all continents and conclude that the similarities (and differences) between creoles can be explained by genealogical and contact processes, as with non-creole languages, with the difference that creoles have more than one language in their ancestry":

It's not clear what's new here, except that having "more than one language in their ancestry" looks like an attempt to shoehorn creoles into the family tree as conceptualized by historical linguists. As some other commenters have said, all languages have some mixture = influence from other languages. What sets creoles apart is the huge discrepancy between the origins of the lexicon (typically overwhelmingly from a single superstrate language) and the origins of the grammar (typically not many features that can confidently be identified as coming from the lexifier language). Of course (e.g.) Haitian Creole could be seen as a changed later form of French — but only if you allow a very long time for erosion of inherited structural features, whereas the lexicon must be considered to be a very recent inheritance from French. What happens in the history of the vast majority of the world's languages, by contrast, is inheritance by daughter languages of both lexicon and grammar from parent languages, with incremental changes from generation to generation. This is the norm even when quite intense contact situations have led to a lot of structural and/or lexical transfer from other languages. (English clearly belongs with non-creoles! There is no gap between the origins of its *basic* vocabulary of English and its grammar: both are derived in a straightforward way from its West Germanic parent. The basic vocabulary of English has only about 14% loanwords, roughly half of these from Norse and half from French and/or Latin.)

There are borderline cases, and they serve in part to highlight the difference between "deep creoles" and non-creoles. Reunionese, for instance, has quite a lot of French grammar, so that the gap between French-origin vocabulary and French-origin grammar is not so extreme; it is best described as a semi-creole. In Mauritian Creole and Haitian Creole, by contrast, there is a huge gap between the French-origin vocabulary (overwhelming) and French-origin grammar (little). Borderline cases like Reunionese also serve to highlight the

fact that creoles did not all arise in the same way: social and linguistic conditions differed from creole to creole. Pidgin/creole specialists have known this for a long time. Typological comparisons like the one these authors apparently relied on, while interesting and often instructive, therefore can't substitute for careful historical analysis. Typologically similar structures can arise from a variety of sources — including convergence toward a prestigious lexifier language from an originally more different creole.

The fact that creoles have structural similarities and differences that are explained by contributions from lexifier/superstrate and substrate languages is utterly unsurprising and has been known to creolists for decades.

And if the authors really make their claim a universal one — NO pidgins in the past of ANY creoles — then they're just flat wrong. As other commenters have pointed out, some creoles have documented histories that include prior well-developed pidgins: Chinook Jargon, Tok Pisin, and others.

Monte Davis said,

September 5, 2017 @ 9:00 am

Long ago I did some research on narratives (archeological, ethnographic/ anthropological, would-be historical) of the transition from hunter-gatherers to settled agricultural and pastoral life… and how they were embedded in metanarratives of progress or, conversely, of decline from the "noble savage." It was hard enough to find primary scholarship that was conscious/cautious of the pull of those metanarratives. And it was almost impossible to find such awareness or caution in what filtered through to social-studies textbooks and journalism about, e.g., the latest "undiscovered" tribe in New Guinea or the Amazon.

I know little about Creoles and pidgins (if any), but I'd be surprised if the same weren't true in this domain. Given (1) how deeply their study is interwoven with [post-]imperial and colonial history, and (2) how readily people draw value-laden conclusions about fine points of their own language (see Language Log on prescriptive usage Nazism, _passim_), it's going to take a long time for the neutrality and nuance of, say, "simplicity/complexity" as used here to make it out to the layman. If only because we all see (and have been) infants learning to speak, and students learning to Speak and Write Right, it's very hard to separate the idea of languages _in statu nascendi_ from "primitive," "immature," "incomplete," etc.

Jonathan Smith said,

September 5, 2017 @ 10:01 am

As an outsider it isn't hard to imagine that there are both respects in which creoles transparently continue pidgin predecessors and respects in which they are arguably categorically different than (and could reflect structural aspects of super/substrate languages more richly than) those predecessors, with this debate being mostly a matter of points of emphasis. Not sure where discussion of Nicaraguan Sign Language stands at present…

David Gil said,

September 5, 2017 @ 10:15 am

Sorry, but I find myself in agreement with both "sides" of McWhorter vs. Blasi et al, and hence don't quite see what the argument is about.

If I understand Blasi et al correctly, they're saying that everything that's in, say, Haitian Creole, comes either from French or from Fongbe, but not from pidgins or from a Bickertonian bioprogram. Now McWhorter seems to think that this assertion runs counter to his view that creoles are simpler than non-creoles. But it doesn't. It could easily be the case that every single feature of Haitian Creole looks at Fongbe, looks at French, and then, in those cases where one option is simpler than the other, chooses the simpler of the two options. In which case creoles would indeed be simpler than non creoles, as per McWhorter, but at the same time Blasi et al would be right about creoles not coming from either pidgins or a bioprogram.

It appears me that McWhorter has a stronger point when he points to clear historically-attested cases where a creole is known to have come from a pidgin, such as Tok Pisin.

Mikael Parkvall said,

September 5, 2017 @ 12:34 pm

David is of course right in theory – a creole could be both simpler than its input languages, and yet derive all its features from them. Yet, in quite a few cases, creoles lack features found in all or virtually all languages contributing to their birth (these are of course, by definition, things that you can live happily without): Genders/noun classes pretty much never make it into creoles, even when found in both the lexifier and the substrates. Ditto for overt copulas, and most inflexion. Even when things are indicated by free morphemes, such as non-core syntactic functions in Japanese and Atayal, the resulting creole does not have such markers.

So – David’s scenario is theoretically possible, but elegant though it is, it doesn’t correspond very well to the actual state of affairs.

John Roth said,

September 5, 2017 @ 12:51 pm

I have to put myself firmly in Bickerton's camp. I understand that to be a rather simple narrative: a number of people from different linguistic groups that are mutually incomprehensible are placed in a situation where they have to communicate and don't have a local prestige language that they have access to learning.

The result is a language of convenience, that is a pidgin. The next generation evolves this into a creole by incorporating some kind of inherent grammatical knowledge. I'd suppose that some parts of the parent's disparate and mutually incomprehensible languages get incorporated (both vocabulary and grammar) – in fact I'd find it difficult to understand why it wouldn't work that way.

Now to beat the horse a bit more: Natural Semantic Metalanguage is a great candidate for that inherent grammatical knowledge. The 65 or so semantic primitives (primes) and their allowed combinatorial possibilities (grammar) are exactly what is needed. If this research holds up (and it's held up through detailed examination of several dozen major and local languages so far) it fills in the missing piece.

David Gil said,

September 5, 2017 @ 1:24 pm

Mikael Parkvall is quite right that my scenario cannot account for all of the simplicity evinced by creoles (as in fact John McWhorter has already pointed out to me in a personal communication).

My point remains, however, that the Blasi et al paper need not necessarily be interpreted as being in conflict with the notion of creole exceptionality.

Etienne said,

September 5, 2017 @ 5:13 pm

All-

The issue of creole distinctiveness has already been brought up here at the log:

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=4600

and

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=4814

and I believe my comments on both threads should answer most non-linguist readers' questions. My offer (on both threads) to supply interested readers with references stands.

To my fellow linguists:

The core problem with the paper is that it pays no attention whatsoever to the known history of creoles. Let us take the lack of French tense- and person-marking bound morphemes in Haitian Creole: the authors ascribe this to Fongbe. PRIMA FACIE this might seem possible, and if I understand David Gil correctly he sees the authors' explanation (language contact without pidginization) as being at least as plausible as the pidgin-to-creole model.

The problem, however (as McWhorter & Parkvall have already pointed out in print) is that the invariable verb of Haitian creole derives, historically, from the infinitival form of the French verb. This is a problem because, while use of the infinitival form is typical of French pidgins, it is utterly alien to any known variety of L1 or L2 French. The (indisputable) fact that (as a rule) Haitian verbs derive from a French infinitival form would remain utterly inexplicable if the authors' model were accepted. It is is quite explicable, indeed expected, if the pidgin-to-creole model is accepted.

And, unfortunately for the authors' model, the above objection does not apply to Haitian only: it applies to most Romance and French creoles as well.

It gets worse. The authors never seem to account for the fact that non-creole contact settings somehow fail to consistently yield the results which creole contact settings consistently yield.

Let us take grammatical gender and its loss in Haitian and other Romance creoles: this is explained as being due to lack of grammatical gender in West African languages. Very well. Several Romance varieties have been in contact with Basque and Hungarian, two languages which also lack grammatical gender. Why is it, then, that the total number of Romance L1 varieties which, through language contact with these two languages, have shed grammatical gender is zero? The contrast with Romance creoles, indeed with creoles in general (where grammatical gender is lost as a rule), is rather remarkable.

This contrast is inexplicable to believers of the authors' model. The pidgin-to-creole model, of course, accounts for this difference. It also accounts for the many instances of creole languages which have lost grammatical gender even if all languages in contact possessed grammatical gender.

David Marjanović said,

September 5, 2017 @ 6:10 pm

I'm less tired now than yesterday (thanks for the editing!) and have read the paper (in Nature Human Behavior, not in Nature, BTW). I find that what the authors really argue against, successfully, is the idea that all creoles have features – Universal Grammar? – in common that cannot be explained by their ancestries and therefore have to be ascribed to the way the brain works. (That seems to be Bickerton's bioprogram idea; my knowledge of the literature is insufficient.) The authors find that there are no such features. The idea that creoles instead have a lack of features in common is not addressed or mentioned.

Then, in the last paragraph, they tell us this shows there are no pidgins in the ancestry of creoles. That simply doesn't follow.

I think it would be very interesting to do such an analysis of pidgins: do they have such universal features in common? I expect not; I predict their grammars, too, can be entirely explained from those of the input languages plus some kind of abstract simplicity (which may derive partly from resorting to the lowest common denominator of the input languages, partly from insufficient input). A stunning case in point may be the fact that Mobilian "Jargon", a Muskogean pidgin, had OsV word order (subject optional): the fact that most creoles have SVO isn't due to a human universal, but to the fact that most creoles are descended from SVO languages, while OsV (absent from all attested languages of the region) is reconstructed for Proto-Muskogean.

Andrew Usher said,

September 5, 2017 @ 7:02 pm

I'll take Jason's definition as the best contribution here: even more succinctly, a creole appears to be an imperfectly learned version of the lexifier language (which is more or less what it historically is). Whether an identifiable 'pidgin stage' existed – and I'm sure it varies – is not really important to the overall picture. Given that a creole, by his and everyone's definition, is now a naturally learned L1, one can't have a negative judgement about its speakers even if one has a negative judgement about creole languages. And again any moral judgements about the status of languages are non-linguistic anyway.

And I note the opposite is true also: I often see the point implied that linguistics has shown that 'all [natural] languages are equal'. Even if that has any assignable meaning it is simply a category mistake to assert that linguistics can prove it; it's just like saying that mathematics shows that people use the word 'infinite' incorrectly.

I am gratified that others here have explained and criticised them on the facts, though I myself saw no need to do that – not because I'm lazy but because I could be sure they were in error from my general knowledge of this type of political argument. Even given that, knowing exactly how they are wrong is of independent interest.

Yuval said,

September 5, 2017 @ 11:05 pm

I read the lexifier geneology comment as a complementary contrast to the earlier-mentioned claim that Creoles are descended only from the substrate (and relexified).

I.e. they're geneology descended from both.

Norval Smith said,

September 6, 2017 @ 1:27 am

I wrote the following as a reaction to a reply by John McWhorter to a simultaneous posting on the Language Log and on Facebook by David Gil.

John McWhorter: "I have argued that creoles like Jamaican and Haitian were born when slaves learned a European language incompletely and built what they learned back up into a regular language. Other linguists say that creoles were born simply when languages mixed together, with no early stage of incomplete learning. "

A weak point in this thesis is the fact that it assumes that slaves would be unable to learn the languages of slave-owners quickly. There would be a high premium on them doing precisely that. It would in fact be a matter of life and death importance to be able to do so.

In the social context of an early Surinam-style colony the proportion of Afrcans to Europeans was such that there would be sufficient exposure to English to make this possible.

Another important human need is to communicate as a group. THe problem for the first slaves was that they spoke different languages. I don't see that there's evidence of incomplete learning, rather of language-mixing of various kinds, with the precise function of self-defence, if you like. As a matter of self-defence, the new (creole) language would be created alongside the various African languages, AND the English they had acquired.

They did then create new languages, but not because they could not learn English. English became the common denominator, the language they shared, so that in Surinam for example, English formed the basis for Sranan, which was created as a means of self-defence, to help them survive.

Of course, in time, slave-owners were able to learn whatever creole languages were spoken in their various colonies, as long as sufficient direct contact was maintained with the slave community, at least. In cases where the colonial languages remained the same as that of the original colonizers their languages also had very significant influences on various linguistic aspects of the creoles.

This is what makes Surinam such an interesting case. The colonial langage was removed fairly quickly, so that we have a much better idea of what the original creole looked like.

It's not possible to summarize the argumentation in Muysken & Smith "Surviving the Middle Passage" in a few paragraphs, but this my thesis at least.

DB said,

September 6, 2017 @ 2:24 am

David Marjanović dixit: The authors find that there are no such features. The idea that creoles instead have a lack of features in common is not addressed or mentioned.

John McWhorter: my point, at least, has been that creolization can create a diagnostic trio of ABSENCES

A feature is not presence only: e.g. having case would be a feature, not having case would be a feature as well. For instance in table 2 there is clearly a creole-related feature that is "no applicative constructions". So if creoles were systematically missing something this would also be part of their cluster.

Also, for the points on morphology (p. 5):

This does not necessarily preclude the existence of other features that are indeed the result of creolization, perhaps in areas not well covered by our data such as morphology. However, our findings indicate that for the overwhelming majority of features analysed there is always a way of showing that they vary with ancestry, that both ancestry and creoles overwhelmingly share one particular feature value (for example, prepositions) or that the ancestral groups are too diverse for our test to yield any definitive conclusion. Thus, the majority of creole grammars have been transmitted—as in any other natural language—from their ancestry, either from their lexifiers and substrates or through later contact (since some of the creoles have coexisted with some of their ancestral languages; for example, Korlai).

So the authors cannot rule out "real" creole features in variables they do not have access to, but that is not the point they make.

boynamedsue said,

September 6, 2017 @ 2:41 am

@Norval Smith

The flaw in your thesis that slaves would have learned the accrolects of their masters as a matter of survival is that it makes assumptions about the nature of contact.

First of all it is far from clear that masters used the accrolect with slaves, there were and are well documented pidgins in use in West Africa, they would have been in use on slave ships and in slave markets on both sides of the Atlantic. It also assumes the ability to correctly learn a language from mere exposure as an adult, this is far from common. There is also doubt as to the level of exposure, plantation creoles are found in areas where the majority of the population were slaves, like Jamaica and Suriname, not places where they were a minority, like black variants of Dutch in NJ/NY or Bermudan English. Field slaves would rarely hear standard English.

Mikael Parkvall said,

September 6, 2017 @ 5:22 am

@David Marjanović: ”I think it would be very interesting to do such an analysis of pidgins: do they have such universal features in common? I expect not; I predict their grammars, too, can be entirely explained from those of the input languages plus some kind of abstract simplicity (which may derive partly from resorting to the lowest common denominator of the input languages, partly from insufficient input)”.

As one of very few people on this planet who has paid special attention to pidgins, and who has consumed pretty much all the available literatue on the subject, I feel I am in a reasonably good position to confirm your hunch. Indeed, pidgins, like creoles share no positively defined features, but are rather characterised by containing only a subset of what any of the input langauges offered – ”simplicity” if you will. (The difference being, of course, that creoles, upon vernacularisation, have by various means expanded their repertoire). To fine-tune your comment, however, it’s not always a question of ”lowest common denominator”, because pidgins rather often lack material shared by both the lexifier and the substrates. (And I dislike the phrase ”insufficient input”, because to my ears, that presupposes that pidgin creotors _wanted_ to learn the lexifier as such, which I doubt, but that is admittedly another subject)

I also agree that the article’s conclusion that creoles don’t develop from pidgins doesn’t follow. For one thing, several of the features can be questioned: some are lexical, for instance, and that creole lexica are derived from their lexifiers has of course never been controversial. Many of the features deal with word order, and as a langauge cannot avoid putting the constituents in some kind of order, that’s a feature that doesn’t stand a chance to be eschewed altogether — and there is no reason to assume that creole creators would depart from the order that the input languages offered just for fun. More interesting features, therefore, would be of the sort that I used in the paper of mine that this article is referring to: gender, evidentiality, suppletion, politeness distinctions, clusivity, articles, alienability are some among many things that no langue _needs_ – as opposed to word order, you cat get by perfectly well without having it. And when considering those, sure enough, creoles do stand out from non-creoles.

A third point is that the method used here fails to detect the continuity of specific morphemes (admittedly true for my method as well). If an input language and a creole share a feature, it is implied that there is some kind of contituity. English creoles (most of which are related) typically have definite and indefinite articles, just like their lexifier. It’s just that these articles aren’t derived from ”a” and ”the”, but from ”one” and ”that” (incidentally, of course, the etyma of the English items themselves). The simplest explanation for Creole WAN ~ DAT vs English A ~ THE is not that the creole in question represents a continuation of the English system, but rather, in my view, that the English system was lost in pidginisation, and later reconstituted in creolisation.

DB said,

September 6, 2017 @ 6:33 am

@Mikael Parkvall

First,

"and there is no reason to assume that creole creators would depart from the order that the input languages offered just for fun"

Actually, in the cognitive sciences there is the wide belief that (e.g.) SVO is a creole feature that comes as the result of creolization (and not from ancestry.)

"More interesting features, therefore, would be of the sort that I used in the paper of mine that this article is referring to: gender, evidentiality, suppletion, politeness distinctions, clusivity, articles, alienability are some among many things that no langue _needs_ – as opposed to word order, you cat get by perfectly well without having it. And when considering those, sure enough, creoles do stand out from non-creoles."

Morphology is not well represented in the data used in the paper (hence my previous comment.) However, some of those features are present and they do turn out to show some association with the ancestral languages (e.g. number, definite and indefinite articles, some gender agreement, etc.) Which takes me to the second point

"A third point is that the method used here fails to detect the continuity of specific morphemes (admittedly true for my method as well). If an input language and a creole share a feature, it is implied that there is some kind of contituity. English creoles (most of which are related) typically have definite and indefinite articles, just like their lexifier. "

This is not the argument made in the paper – in fact, there are no statements about which specific languages were ancestral to the creoles (which is a big issue in the field.) If it is found that there is a systematic, statistically-detectable association between the coarse ancestral groups (e.g. Romance/Germanic/Other) and the feature values of the variables analyzed, then one should explain why independently most languages lexified by Romance languages prefer X whereas languages lexified by Germanic languages prefer Y.

Also, I think one of the main points of discussion here has to do with the very definition of what a pidgin is (as suggested by Gil.) If you define "pidgin" as a fully-functional **language** that simply lacks some specific pieces of (seemingly not necessary) morphology, then I don't see any conflict with the message of the paper. Instead, if you adopt the definition that a pidgin is a restricted communication code with limited productivity, then you'll need to explain how is that the creoles that supposedly emerge from them tend to exhibit features present in their ancestral languages while they were not present in the pidgin. Independent innovation or loss of structure will be at odds with the patterning along the lines of the ancestry.

That said – it would be certainly interesting to see what happens with pidgins in a similar evaluation (perhaps with more morphological coding.)

Mikael Parkvall said,

September 6, 2017 @ 7:09 am

DB: Actually, in the cognitive sciences there is the wide belief that (e.g.) SVO is a creole feature that comes as the result of creolization (and not from ancestry.)

MP: True – I tend to forget that, but that is a point where I am in complete agreement with you. There is no specific SVO preference in creoles.

DB: Morphology is not well represented in the data used in the paper (hence my previous comment.) However, some of those features are present and they do turn out to show some association with the ancestral languages (e.g. number, definite and indefinite articles, some gender agreement, etc.)

MP: It doesn’t have to be morphology in the traditional sense of bound morphemes. In fact my article (and that’s a point many have missed about it) tried to avoid it. As opposed to many others, I explicitly excluded boundedness from my definition of complexity.

If, however, you use ”morphology” in the more liberal sense of ”any use of grammatical morphemes”, then I think there should be more talk about it, because that’s pretty much what creolisation (and pidginisation) is all about.

DB: This is not the argument made in the paper – in fact, there are no statements about which specific languages were ancestral to the creoles (which is a big issue in the field.) If it is found that there is a systematic, statistically-detectable association between the coarse ancestral groups (e.g. Romance/Germanic/Other) and the feature values of the variables analyzed, then one should explain why independently most languages lexified by Romance languages prefer X whereas languages lexified by Germanic languages prefer Y.

MP: That’s why I wrote ”implied”, but maybe that was an overstatement as well – I’ll re-read the paper. But many (not all, though) of the features are such that you have to go with either option X or option Y, and so the pidgin I believe preceeded the creole had to choose one, and it is not extraordinaily surprising that the creators got ”inspiration” from languages they already spoke.

Just to be clear: a pidgin is not devoid of grammar (though that is the sense in which Bickerton has used the word), nor is it devoid of grammar traceable to the input languages. The crux of the matter here is that I suggest creoles were preceeded by a stage in which _most_ of the grammar from the input langauges was lost, whereas you seem to claim that _most_ was retained. This obviously has to do with us working with differnt datasets, and thereby it turns into a question of which one best represents ”most” of language.

DB: Also, I think one of the main points of discussion here has to do with the very definition of what a pidgin is (as suggested by Gil.) If you define "pidgin" as a fully-functional **language** that simply lacks some specific pieces of (seemingly not necessary) morphology, then I don't see any conflict with the message of the paper. Instead, if you adopt the definition that a pidgin is a restricted communication code with limited productivity, then you'll need to explain how is that the creoles that supposedly emerge from them tend to exhibit features present in their ancestral languages while they were not present in the pidgin. Independent innovation or loss of structure will be at odds with the patterning along the lines of the ancestry.

MP: There is of course an annoying continuum here. An early pidgin is ”fully functional” in restricted domains, but apparently not (hence creolisation, which, let us not forget it _has_ been directly observed in ome places) enough for people in all walks of life. This then gradually develops into a creole, which in terms of expressivity of course is as ”functional” as any human language. This did not apply overnight, but presumably in the same pace as the new language took over more and more domain.

As for the carryovers from input languages – some of them were there all along (since pidgins do contain stuff beyond the lexicon that is derived from the input lgs), but others are likely to have been introduced in the expansion phase. For most (though not all) creoles, both the lexifier and the substrates were still around, and could provide more ”inspiration”.

Etienne said,

September 6, 2017 @ 2:28 pm

@Norval Smith : you wrote, on McWhorter's thesis:

"A weak point in this thesis is the fact that it assumes that slaves would be unable to learn the languages of slave-owners quickly. There would be a high premium on them doing precisely that. It would in fact be a matter of life and death importance to be able to do so.

In the social context of an early Surinam-style colony the proportion of Afrcans to Europeans was such that there would be sufficient exposure to English to make this possible."

Learning English (or whatever the dominant language was) was indeed possible, but not inevitable. What was a matter of life and death importance to slaves was the ability to communicate, with slave-owners and fellow slaves alike: and for adult learners learning a pidgin is much easier than learning the lexifier (As Philip Baker pointed out, pidgins should be regarded as optimal solutions to immediate problems of inter-ethnic communication, rather than as the outcome of failed acquisition of a language).

What the demographic ratio (of Blacks to Whites) of early creole-speaking societies indicates was that pidgin speakers did not heavily outnumber speakers of the lexifier: meaning that (as Mikael Parkvall points out, in answer to DB) the latter could and did heavily influence the former.

@DB: I'd like to amplify my point above on the contrast between creole and non-creole contact outcomes. Because it seems to me that, even if you could account for creole structure solely on the basis of the typological traits of the languages in contact (which I do not believe is the case: cf. my point upthread on the French/Romance infinitive as the basic form in creoles), you would still need to account for the uniformity of the linguistic outcome in creoles, which stands in remarkable contrast to the observed outcome of language contact between typologically dissimilar languages yielding non-creole contact languages.

I gave the example of grammatical gender above, which seems, in creole genesis, to be eliminated quite consistently in a way that is not observed in non-creole instances of contact involving a language with and another without grammatical gender. Another instance involves number agreement within the NP, which is well-nigh absent in creoles, even those which make use of a bound morpheme marking the plural (cf. Cape Verdean and Guinea-Bissau Portuguese Creole, for example). Now, your model would explain this loss as being due to the impact upon European languages of West African languages lacking such agreement. Let us grant this. This brings up the question: why would a West African substrate always systematically eliminate this feature, time and time again, in the history of every creole?

The question is all the more legitimate if we consider that, in Europe, the Fennic branch of Uralic, which does display agreement (in case and number) across the NP, has been argued to owe this innovation to contact with its Indo-European neighbors (Germanic, Baltic or Slavic): conversely, much of East Slavic has expanded at the expense of various Uralic languages over the past thousand years or so. The number of Uralic-influenced East Slavic L1 varieties which, through Uralic influence, have lost grammatical gender and/or agreement within the NP is, to my knowledge, zero.

Do you (or indeed does anyone on this thread) have any thoughts on how this startling difference between the outcome of language contact yielding creoles and of language contact yielding non-creoles might be accounted for?

David Marjanović said,

September 8, 2017 @ 1:15 pm

No, that's what an early pidgin is. Creoles have elaborated on that. (And so, most likely, have pidgins that were in wide use for centuries but didn't acquire native speakers.)

Of course not! What would be of such importance was the ability to understand commands. That's pretty much it.

Comparable early pidgins formed on construction sites throughout Germany and Austria in the late 20th century, where most of the workers came from then-Yugoslavia and Turkey. What happened? German words, loss of gender (gender-indicating endings being used at random or becoming part of the word), a small subset of the German word order rules, a subset of the German sound system, loss of tenses and conjugation in favor of the infinitive = dictionary form of the verb, loss of articles… loss of all the stuff that isn't usually critical to understanding in a limited set of situations.

The foremen contributed to this: to make sure their instructions were understood, they left the extraneous stuff out. Add a few cycles of mutual imitation, and you get to the stereotypical formula for firing someone, which I'll gloss:

Nix Problem, Kollega – anderes Baustelle!

Nix is a widespread dialectal form of nichts, meaning "nothing". Ungrammatical here in all natively spoken kinds of German, but why bother distinguishing several negations? The intent is clear.

Problem is straight-up Standard German.

The -a on kolega is not German (Kollege), but of course shared by a lot of surrounding languages, including at least one of the common native languages of "guest workers".

anderes "other" is neuter, not agreeing with the feminine Baustelle "construction site". It appears, grammaticaly, in the common phrase (et)was Anderes "something else", and may have spread from there.

What can I say, stuff got built, so it seems to have worked.

Sure. The situations you mention involved slowly learning a whole language and trying to sound like a native speaker in one's whole daily life, not quickly learning just enough for just one or two narrow purposes.