Ayiti Pare

« previous post | next post »

"MIT and Haiti sign agreement to promote Kreyòl-language STEM education", MIT News Office 4/17/2013:

MIT and Haiti signed a new joint initiative today to promote Kreyòl-language education in the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) disciplines, part of an effort to help Haitians learn in the language most of them speak at home. […]

The idea that more Haitian education should occur in Kreyòl is a longtime belief of MIT linguistics professor Michel DeGraff, a native of Haiti, who has contended that Kreyòl has been improperly marginalized in the Haitian classroom. DeGraff’s extensive research on public perceptions of Kreyòl, and on the language itself, has led him to assert that its perception as a kind of exceptionally simplified hybrid tongue, in comparison to English or French, unfairly diminishes the language.

The initiative is meant not to replace French, DeGraff added, but to help Kreyòl-speaking students “build a solid foundation in their own language.”

The technology-based open education resources, he noted, are meant to promote “active learning,” as opposed to drill-based rote learning techniques.

The initiative is being funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and by MIT.

According to this video, "Ayiti Pare":

[Full disclosure: as an undergraduate, Michel DeGraff was an intern in my department at Bell Labs in 1985, and he got his PhD from Penn in 1992 — in computer science.]

Update — The comments below about the nature of "Creole languages" represent a standard view, which Michel has argued is spectacularly wrong. For a clear presentation of his arguments, see the slides from his presentation in the AAAS 2013 symposium on Historical Syntax, "A Null Theory of Creole Formation". The abstract:

Creole languages have traditionally been excluded from the scope of the Comparative Method in historical linguistics. To date, the most persistent and popular theories of Creole formation claim that Creole languages constitute an exceptional “Creole typology” whose members lie outside well-established language-family trees. Furthermore Creole languages are often claimed as the least complex human languages. Another view takes Creoles as relexified versions of their substrates. Our ongoing work suggests that these claims are all mistaken. We’ve argued that Creoles duly fall in the scope of the Comparative Method as languages genealogically affiliated with their lexifiers. Here we offer the bases of a framework for a null theory of Creole formation, a theory that we believe is empirically more adequate than the popular exceptionalist claims. This null theory does away with any sui generis stipulation that applies to Creole languages only. Instead it is rooted in basic assumptions and findings about Universal Grammar—assumptions and findings that apply to all languages. In this approach, the creation of new languages, whether or not they are labeled “Creole,” sheds lights on the interplay of first- and second-language acquisition as new grammars are built from complex and variable input. The effects of this interplay are similar across familiar cases of Creole formation as in the creation of Haitian Creole and familiar cases of language change as in the history of French or English. Such null theory undermines various traditional claims about “Creole simplicity” and “Creole typology” whereby Creoles are considered exceptional languages of lowest complexity. This approach also makes for a better integration of Creole phenomena to our general understanding of the cognitive bases for language change.

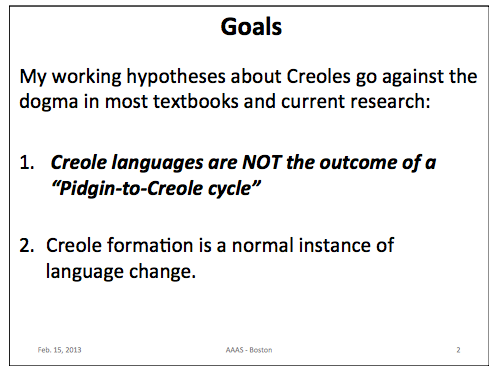

Or, more succinctly and in larger type, the first slide from Michel's presentation:

As you can see from Sally Thomason's comment, aspects of this view remain controversial — but if you're interested in such things, and have uncritically accepted the recently-standard wisdom on the subject, I recommend that you read through Michel's slides to learn more about the issues.

Jason said,

May 2, 2013 @ 11:03 pm

The idea that more Haitian education should occur in Kreyòl is a longtime belief of MIT linguistics professor Michel DeGraff, a native of Haiti, who has contended that Kreyòl has been improperly marginalized in the Haitian classroom. DeGraff’s extensive research on public perceptions of Kreyòl, and on the language itself, has led him to assert that its perception as a kind of exceptionally simplified hybrid tongue, in comparison to English or French, unfairly diminishes the language.

I haven't studied Kreyòl, but if it's anything like the creoles I have studied, that's precisely what it is! An exceptionally simplified hybrid tongue. But that's precisely the appeal of creoles — they are utterly, relentlessly logical, regular, simple and consistent, from their genesis in pidgins learned only as a second language. I can learn Bislama at roughly five times the pace I learned French. Computer scientists are impressed by the simplicity and elegance of languages like Lisp. Well Bislama is the Lisp of natural languages. So Eurocentric to assume that a roccoco array of arbitrary genders, a plenitude of popolysemous prepositions and an array of inexplicable inconsistencies are the measure of a "real language." Why does the writer portray a language as inferior because it lacks unnecessary complexity?

It's good to see a creole getting some respect.

Catharine Cellier-Smart said,

May 2, 2013 @ 11:36 pm

Well said Jason!

Aaron Toivo said,

May 2, 2013 @ 11:57 pm

Jason: While I also am happy to see Kreyol get some respect, you seem to be overblowing the "relentless logic" of creoles somewhat. They are well known to have more simplicity and regularity than regular languages (if we can ever finally settle on what those notions should even quite mean), but they are still languages as highly adapted for human expressivity as any other. Give any of them enough centuries in which to develop and you'll see it grow rife with irregular verbs, or discontinuous morphemes, or asymmetric half-fusional person-number paradigms, or long lists of irregularly-gendered case-marking postpositions that double as typologically rare pragmatic status particles, or some other big headache for the learner. Languages do strange things. Creoles are no exception, they just haven't had enough time to collect a full set yet.

Meanwhile, if you find such languages as English or French to be terribly irregular and illogical, you should study syntax. Especially if you like Lisp, you'll love syntax. You may learn just how relentlessly, frighteningly logical you never noticed your own language is.

NW said,

May 3, 2013 @ 3:47 am

Although I'm sure Bislama is logical, European-speakers might be surprised at calling it simple when they find it has dual, trial and plural pronouns, as well as inclusive and exclusive first singular, as the local native languages have.

Barbara Partee said,

May 3, 2013 @ 4:48 am

Michel DeGraff would argue with all three of you:

From Michel DeGraff, ‘Linguists’ most dangerous myth: The fallacy of Creole Exceptionalism’ Language in Society 34:4 (2005). http://web.mit.edu/linguistics/people/faculty/degraff/degraff2005fallacy_of_creole_exceptionalism.pdf

… Worse yet, neo-colonial and exceptionalist creolistics, especially within Creole communities, eventually infringes on the human rights of Creole speakers. … The most powerful tool of domination, both actual and symbolic, is the school system, which in much of the Caribbean still devalues Creole languages – even in Haiti, where the vast majority of Haitians speak only HC [Haitian Creole], where all Haitians speak HC, and where HC is an official language on a par with French. The nonuse or limited use of HC in Haitian schools violates the pedagogically sound principle that “education is best carried on through the mother tongue of the pupil” (UNESCO 1953:6, 47). Such de facto stigmatization and/or exclusion of HC in the schools and in other formal spheres effectively makes monolingual HC speakers second-class citizens. …

[How to rectify the problems?:] On the practical and pedagogical side, Universal Grammar (UG) leaves no room for the fantastic and fatalistic, but still widely believed, orthodoxy according to which Creole languages constitute a “handicap” for Creole speakers and cannot be used as viable media for, and objects of, instruction. So, in principle, a creolistics that is informed by Cartesian-Uniformitarian linguistics may help provide Creole languages and their speakers with, among other things, “capital” that is both symbolic, in Bourdieu’s 1982 sense, and real, in the sense of economics.

(pp 577-78)

Avinor said,

May 3, 2013 @ 5:02 am

If you want to make the point that it is a full language of its own, why not simply call it "Haitian" instead?

Sarah Thomason said,

May 3, 2013 @ 6:39 am

DeGraff is wrong to link claims of creole simplicity with claims that creoles don't fit into family trees. He's also wrong, I'd say, to claim that creoles are "traditionally" viewed as falling outside the reach of the Comparative Method — well, depending on what you mean by "traditionally". At least until the publication of Thomason & Kaufman 1988 (Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics), and maybe still today, most specialists viewed creoles as descendants of their lexifier languages. On that view, Haitian Creole is a descendant of French, Jamaican Creole is a descendant of English, and so forth. Kaufman and I argued that that's a mistake: the Comparative Method requires systematic correspondences in grammar as well as lexicon, and in Haitian Creole, Jamaican Creole, Tok Pisin (Papua New Guinea), etc., the gap between lexical and grammatical correspondences is enormous: up to 90% lexical matches between creole and lexifier, few if any systematic grammatical correspondences between creole and lexifier. That's not how the vast majority of languages change, as evidenced by dozens of well-established language families all over the world, whose members show systematic correspondences throughout the lexicon and the grammatical structures. A creole cannot reasonably be viewed as primarily a changed later form of a single parent language; and only languages that can be viewed as descended primarily from a single parent language can be placed in a family tree, because they are not amenable, as whole languages, to classification and reconstruction by means of the Comparative Method, the only reliable method we have for genealogical classification. (Most current computational methods of classifying languages do not take grammar into account, so they'll have no trouble classifying creoles with non-creoles into language families. That's a major reason why most historical linguists remain skeptical about those methods.)

I agree with DeGraff on the question of maximum simplicity and creole typology, though. And I agree with him at a deeper level on the issue of processes of change: I don't think speakers' strategies of language creation differ all that much from their strategies in other kinds of language learning; it's only the result that's strikingly different. DeGraff is more optimistic than I am about the role of Universal Grammar — I think social factors (e.g. lack of a true target language for shifting adult speakers, and/or lack of access to the lexifier language) are much more important in creole genesis — but, like him, I don't think the processes of change and creation, in the form of speakers' behavior, differ profoundly between language change and creole genesis. The time scales do differ dramatically: creoles emerge in something between one generation and several; ordinary language change (as opposed to new language creation) is a *lot* slower. That's why modern English speakers can still read Shakespeare, for instance.

I also disagree with DeGraff in his apparent belief that the pidgin-to-creole cycle is bogus. Some creoles, quite possibly Haitian Creole included, may well have had no stable pidgin stage. But others did. Tok Pisin is a prime example: it existed as a stable pidgin for maybe a hundred years, expanding into new societal domains and creolizing (acquiring native speakers) quite late.

In any case, I do believe in creole exceptionalism, to use DeGraff's term — but only in the historical sense. That is, in my opinion creoles differ from non-creole languages only in the timing and manner of their emergence. The bursts of creativity that produced creoles (and pidgins as well) are a testament to the human capacity for responding effectively to challenging linguistic circumstances.

nominalize said,

May 3, 2013 @ 7:17 am

If we untethered the definition of creole from coming from a pidgin, then the Modern Hebrew that arose in Israel would probably qualify; the words are largely borrowed from a lexifier (ancient Hebrew), but the grammar quickly became very different (and many would say simplified) through natural acquisition processes.

Coby Lubliner said,

May 3, 2013 @ 10:22 am

@ nominalize: It's very likely that in 19th-century Jerusalem a kind of pidgin Hebew was spoken among the various Jewish communities, whose home languages may have been Yiddish, Judaeo-Arabic, Judaeo-Spanish etc., but in which most people had a least a smattering of Hebrew. (A. B. Yehoshua has commented on this.)

Also, there is a very good change that most Romance dialects (including those that "grew up" to be "languages," such as French) began life as creoles. Speakers of various Celtic and other languages probably used pidgin Latin to communicate with one another and with Roman soldiers (most of whom were not native Latin-speakers either), and then the usual creolization process took place.

Something similar can probably be said about English.

There appears to be a political motivation behind Michel DeGraff's stance, which I don't really grasp. What's wrong with pidgin-to-creole, anyway?

J.W. Brewer said,

May 3, 2013 @ 10:33 am

Do any of the current academic proponents of the hitherto standard view Prof DeGraff is contesting (i.e. that creoles are unusually regular or non-complex) believe that this is a reason they should not be used as languages of instruction in general or for STEM subjects in particular, or is this a strawman argument? I would be surprised if very many currently-tenured creolists had made such a claim (not least because the same features than can be described as showing lack of complexity can also be spun the other way as showing logic and regularity), and the linkage of the issues makes me skeptical about his larger project. Perhaps the truth shall set you free, but claiming (as in the 2005 piece linked above) that the self-esteem and political/social status of creole-speakers depends on which side in a fairly abstract scholarly controversy is right (or, perhaps, which side is believed to be right by non-specialists, which is not exactly the same thing . . .) seems not only implausible (although perhaps a typical case of academic nerdview overvaluing the importance of ones own obscure specialty in the grander scheme of things) but actually imho undermines Prof. DeGraff's own credibility a bit. Academic discussions as to the ancestrally hybrid or possibly even creolized nature of English (Romance relexification? traces of Celtic substrate?) do not undermine the self-esteem or political/cultural status of Anglophones, do they? Similarly, the relative prominence of say Afrikaans and Xhosa in the educational systems of apartheid South Africa had nothing to do with their relative "complexity," since if anything it's Afrikaans that has a bit of stereotypical creole simplicity. Indeed (if one is willing to swallow the irony and take lessons from that quarter . . ,), the historical/political processes by which Afrikaaners decided to stop using standard literary Dutch for various formal public purposes and instead use the language they actually spoke and be proud of it rather than thinking of it as inferior could be an interesting role model for Haitian Kreyol.

The points made in the 2013 slides linked in the original post as well as the criticisms of them in the thread are quite interesting, but I think that controversy would be better pursued by isolating it from (imho dubious) claims about the secondary real-world consequences of one view or another being adopted.

Dan Lufkin said,

May 3, 2013 @ 1:56 pm

I back-translate a lot of patient information documents, informed-consent forms, and the like from Afrikaans. Afrikaans has a quality that I think of as "spit it out in daddy's hand." It just gets the job of communicating done with a minimum of fluff. I know perfectly well that you can obfuscate and bloviate in Afrikaans, but the everyday use of the language has a great no-nonsense feel to it.

I like Papiamentu, too. Very economical with verbs.

Sybil said,

May 3, 2013 @ 2:06 pm

I realize this is kind of implicit in some of the comments above, but…

The issues of whether the "Pidgin to Creole" cycle is a valid model (or whether Creoles are "true" languages, or whatever) , and whether or not to teach in Haitian Creole, are separate issues, I think.

I've had to deal with the analogous issue with respect to various forms of Latin American Spanish, which (I think) no one doubts is (are?) a language.

Not weighing in on one side or the other of the issue, just sayin'…

(The discussion about Creoles is very interesting though. Carry on!)

Ken Brown said,

May 3, 2013 @ 5:05 pm

As Avinor implied – why not just call it Haitian? – doesn't this boil down to a claim that Haitian is not in fact a creole in the theoretical sense, that is a highly elaborated descendent of a pidgin, but rather it is a normal language produced by normal processes, a new member of the Latin family tree ?

Whether or not any such "true" creoles exist is a different question.

Eric Vinyl said,

May 4, 2013 @ 5:10 am

@nominalize

You may want to check out Ghilʾad Zuckerman’s work on “Israeli.” In fact, there are those who assert that Modern Hebrew is just Semitically lexified Yiddish.

Also, I’ve been thinking about Afrikaans and Afrikaners’ status vis-à-vis Hawaiian Pidgin lately. And Papiamentu

Jason said,

May 4, 2013 @ 10:55 am

@NW

Although I'm sure Bislama is logical, European-speakers might be surprised at calling it simple when they find it has dual, trial and plural pronouns, as well as inclusive and exclusive first singular, as the local native languages have.

I will take that over grammatical gender and irregular verbs any day of the week. (I think there are around 10 irregular verbs in Bislama, all of which are merely verbs which should have a transitivity marker, -em, but don't.) All tense/aspect/modality is done with separate, orthogonal particles.

Compare this with the conjugation of french être!

I'm simply saying the neo-melanesian creoles have very little unnecessary complexity, mindless grammar such as gender agreement, irregular verbs or complex conjugation paradigms, that bedevil European languages. The single/dual/trial distinction is part of the semantics of Bislama, not its ceremony, as are the often difficult serial verbs. (Again, nearly always consistent – the serial verb complement "… i go long…" in "mi wokabaot i go long stoa" (I walk to the store) for example, consistently indicates the direction of action of the main verb. Unlike the dilemmas of, say, en or à in French.)

Peter Erwin said,

May 4, 2013 @ 11:13 am

Coby Lubliner:

… and then the usual creolization process took place.

Something similar can probably be said about English.

The articles I've read on the topic would suggest that's not the case. It turns out that a number of what look like dramatic changes between Old and Middle English — and which some people have ascribed to an Angle-Saxon/Norman-French "creolization" process — were already underway in some Old English dialects prior to the Norman Conquest, and some of the same simplifications (e.g., erosion of the grammatical gender system) have also taken place in Dutch, albeit more slowly and not quite as thoroughly.

(Given that, I'd be pretty skeptical about Latin-to-Romance-Language change as "creolization" as well. For one thing, we know that a lot of the change was pretty gradual: you can see progressions from Classical Latin to Vulgar Latin to Late Latin to early Medieval forms of French, etc.)

Jason said,

May 4, 2013 @ 11:17 am

@Barbara Partee

Well, having read your quoted article, Michael DeGraff seems to have delivered quite the post-colonial rant, worthy of Edward Said himself, but he definitely caricatures McWhorter, for one, and Locke, who may well have been a hypocrite but who never made any argument even similar to the "degeneracy theory" that DeGraff claims he did. Like Said, you can prove the irredeemable bias of Western scholarship by cherry-picking dated pre-20th century writers and claiming it's all of a piece with modern scholarship, but his long fantasy screed of victimization is highly selective of modern writing — for example, Francis Mihalic's writings on Tok Pisin in the 1950s, which are nothing if not complementary of the language's expressive power. (Mihalic's enthusiastic admiration of the language and his choice of it for the newspaper "Wantok" may even be a factor in why Tok Pisin won over Police/Hiri Motu in becoming the lingua franca of PNG.)

The old stereotype of the creole as the "simple, rudimentary, clumsy jargon incapable of expressing abstract thought" hasn't been true of linguistic science since the fifties, and the debate about whether creoles have a characteristic syntactic simplicity is not an extension of this stereotype, but an orthogonal debate. As JW Brewer has argued above thread, "simplicity" itself can be valanced in multiple ways — for most computer scientists "simplicity", "elegance" and "power" are things to strive for in a language.

OTOH, I have been convinced from my own reading that Bickerton is close to being discredited at this point and the dominant Bickertonian thesis of the pidgin-creole cycle and the bioprogram hypothesis probably is badly wrong, so I agree with DeGraff on that point — but can't one be wrong without being implicated in some alleged indissoluble racism characteristic of (and only of) the west?

Jake Nelson said,

May 4, 2013 @ 5:50 pm

The linked DeGraff piece comes off as incredibly defensive to the point of petulance, and that's despite my largely agreeing the points it's trying to make.

As a note, non-linguist acquaintances I talk to about language sometimes associate "Creole" with "Creole cooking" and "Creole people" (referring to Louisiana Creole), and sometimes Haitian Creole, but "creole languages" seems weird to them. As such, they (and now I) tend to say "hybrid languages", which I think is an excellent term for a number of reasons, and generally a positive one.

I also find DeGraff's example of genetic vs. creole using English as genetic and Haitian Creole as a creole to make an odd conclusion. Yes, English is "more of a creole" than Haitian Creole in many ways- that doesn't necessarily make Haitian Creole "genetic" instead of "creole" if one accepts that distinction and those terms, it could also mean they're both creoles, which I think is more accurate.

Overall, I'm often impressed by how nearly identical the struggles of linguists and biologists with regard to family trees are. Biologists have a lot of issues right now with regard to both "classic" hybrid animals (like the question of the red wolf's status, which affects its position as an endangered animal or not) and the ever-growing implications of lateral gene transfer (which has shown that not only is a traditional family tree largely meaningless for bacteria, but that many multicellar organisms can be said to inherit a large portion of their genes from sources other than their traditionally-considered "ancestors"). It has a strong "fall of Platonism" feel, like the Uncertainty Principle devastating the classical physical notion that with the right instruments, we could deduce all of existence mechanically.

Mind you, I've always felt the effort to describe languages as singular entities rather bizarre. To me, a "dialect" is a mutually intelligible intersection of idiolects, and "language" is polysemous: either a governmentally-established "standard language" (the old "dialect with an army and a navy") or a "dialect family" (a mutually-intelligible intersection of dialects).

David Marjanović said,

May 4, 2013 @ 7:24 pm

Uh, that's a feature of the datasets that have been used so far, not the methods. Nothing stops you from using grammatical features as characters in a data matrix for phylogenetic analysis.

Etienne said,

May 4, 2013 @ 9:29 pm

As a dabbler in issues relating to creoles and language contact I thought I might as well jump in…

1-J.W. Brewer: not a single present-day proponent of the pidgin-to-creole model of creole genesis, to my knowledge, has ever claimed that creoles are thereby structurally inadequate or should not be used as official languages or languages of education. Sybil: you are of course correct, these are two wholly separate issues. It should be added that of the world's 6000 languages, *most* are excluded from prestigious functions (medium of education, official written documents…), so that any attempt at establishing a connection between theories of creoles as "special" languages on the one hand and their being excluded from prestigious functions seems doomed to fail.

2-Jason: You have pretty much hit the nail on the head. YES, *of course* Bislama is simpler than French or German!

And this is a fact, not some bias due to hegemonic eurocentric bla bla bla [INSERT FASHIONABLE SEMANTICALLY EMPTY BUZZWORDS HERE]: after all, Bislama, like Haitian, is the dominant vernacular of a nation-state, unlike languags such as Occitan, Gaelic or Frisian, yet oddly enough Occitan, Gaelic or Frisian do not appear simpler than Haitian or Bislama.

Hmm, could race be the issue? Well, there are plenty of languages spoken by non-whites that are not the dominant vernacular of a nation-state either: Navaho, Cree, Saami, Yakut, Fulani…okay, Bislama and Haitian are obviously simpler than any of them, so their being called simple might be due to…err…maybe to the fact (keep your voices down! Hush! Send the kids away!) that they ARE simpler?

3-Sarah Thomsason: unlike you I believe creoles are nativized pidgins, and unlike you I also believe that creoles such as Haitian or Sranan can be considered to be members of the Romance and Germanic families, respectively.

But my reasons for believing these two things are separate.

I believe Haitian is a nativized pidgin because Haitian is to French what Bislama (the latter indubitably a pidgin acquiring native speakers) is to English: that is, a language with (a subset of) French/English vocabulary but with no French/English inflectional morphology. Because non-pidgin, non-creole varieties of French or English do not exhibit such heavy lexical or total inflectional loss, even varieties which have otherwise undergone very similar external histories (Francitan, Western Canadian Metis French, Houma French, Hiberno-English, Lumbee English, AAVE all come to mind), and because we can observe pidgin languages nativizing today, it is only natural to assume that languages such as creoles, which share features with pidgins to the exclusion of all non-pidgin varieties of French/English (Actually, Romance and Germanic, if you broaden the scope of inquiry), are themselves, historically, nativized pidgins.

As for my belief that creoles are unproblematic for a family tree model: this is because the presence or absence of shared grammatical features between languages is wholly irrelevant to the isssue as to whether or not the languages are related. A family tree describes a historical reality, not a synchronic one: read Antoine Meillet's work on the subject (I would be happy to give anyone here some references downthread, should it be requested), he makes this point far more clearly and lucidly than I ever could.

4-From a practical point of view the fact that English or the Romance languages have been suspected of having been themselves creolized to a degree makes the exclusion of creoles from a family tree classification problematic: if the suspicions of a creole past for English or Romance are shown to be true, would we have to claim Romance languages and English are non-Indo-European?

Moreover, what of the various mesolectal forms of speech spoken in countries such as Trinidad or Jamaica, which are neither "pure" creole nor standard English, yet partake of both, linguistic features-wise? How are they to be classified? Well, I think all are Germanic, but I would like to know where scholars such as Sarah Thomason would draw the line in these and similar such cases.

5-Pidginization and creolization differs from other types of language contact inasmuch as pidgins/creoles undergo massive losses, which are quite similar world-wide. Other types of language contact involve losses as well as gains. Take the contact which took place between French and Cree in the Canadian West: it yielded the birth of new dialects of French and Cree spoken by the Metis, and of a mixed language, Mitchif. Tellingly, nowhere do we find a pidgin- or creole-like pattern of total inflectional loss: what we do find is a pattern of exchange of morphemes, vocabulary and phonology, which often yields new structures which are more complex than those of either original donor language(s).

For this reason I believe calling creoles linguistic hybrids is inadequate: Mitchif is a linguistic hybrid, but it is radically unlike Haitian or Bislama.

Eric Vinyl said,

May 5, 2013 @ 4:29 am

Mr. Erwin:

A minor clarification: Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin were contemporaneous; Classical Latin was a formalized, prestige register, it did not “devolve” into Vulgar Latin.

Mr Punch said,

May 6, 2013 @ 9:13 am

The reality is that it's much more valuable to know a language used by hundreds of millions of people, some of them very prosperous, than one spoken by a few million people, almost all poor. So there's that.

Spanish and Portuguese exist is variant forms in different countries, though I don't know how differentiated they are compared to French/Kreyol; and Arabic, I believe, varies more. The issues around these languages do not seem as prominent however.

J.W. Brewer said,

May 6, 2013 @ 10:36 am

Mr. Punch: sure, but no one begrudges the right of e.g. Estonian high school students to study physics and calculus in Estonian (unless possibly such instruction is being forcibly imposed on the Russophone minority, which is a different issue . . .). One assumes they remain sufficiently motivated to learn one or more non-Estonian languages that will be of economic benefit to them. I do expect that if one were to rank all of the ways Haiti's numerous and interrelated structural problems and poverty might be ameliorated, promoting Kreyol-language STEM instruction is not going to be one of the first 10 or 20 or 50 initiatives in which one would get the most bang for ones marginal buck (or marginal several million bucks). But it's only an affirmatively bad thing (from the POV of Haitian well-being) if it will cause relevant resources to be diverted from something more worthwhile, which is possible but certainly not inevitable.

Salikoko S. Mufwene said,

May 9, 2013 @ 5:11 pm

Let me respond globally to some of the preceding postings with just some brief remarks.

We have been reopening the books about the emergence of creoles because some of the claims do not jive with the history of trade colonization in Africa and settlement colonization in both the New World and the Indian Ocean. The slave trade was a very well organized industry involving powerful indigenous middlemen in Africa who were invested in learning the language of the European traders and often sent their children or relatives to Europe to learn the relevant European language. More and more history books mention the important role played by interpreters during this trade, suggesting that pidgins may have emerged just about the same time creoles did in the New World or perhaps even later. No Africa-based pidgins could have served as antecedents of creoles in the New World of the Indian Ocean. The contact conditions in the New World's and Indian Ocean's homesteads and, later, the plantations were not conducive the emergence of pidgins, which have typically been associated with sporadic contacts. The creoles we have been talking about are the ones often characterized as "classic creoles" in creolistics, those lexified by European languages and typically found in the New World, especially the Caribbean, and in the Indian Ocean. Varieties such as Tok Pisin (comparable to Nigerian Pidgin English!) have been identified as "expanded pidgins." The contact settings associated with the latter are not of the same kind as those associated with the "classic creoles." Using a dangerous analogy, creoles are like half-empty bottles whereas expanded pidgins are like half-full bottles. That difference in history is a significant one. So Tok Pisin is hardly counter-evidence to the hypothesis that creoles have not evolved from antecedent pidgins.

Regarding the genetic classification of creoles, I think Hugo Schuchardt was the first to claim creoles had a mixed ancestry, but then Louis Hjelmslev went as far as claiming, in a 1938 article, that Indo-European languages (or was it all modern languages?) too have mixed ancestries. In the 1970s, some scholars (Charles Bailey and Brigitte Schlieben-Lange in particular) suggested that even English and the Romance languages can be called creoles. All these scholars were pointing out the embarrassing issue of ignoring the role of language contact in language speciation/diversification in some cases and invoking it to bear so heavily in some others. As far as I know, nobody has applied the comparative method (systematically) to creoles and most studies are misinformed because the few comparisons that have generated a lot of literature have compared creoles with standard varieties of the European languages, not with the nonstandard varieties that the African slaves were exposed too. Could the received position on the exceptionality of the emergence of creoles reflect forgone a forgone conclusion inherited from the 19th century?

The above background is important to understand the empirical weakness of creole exceptionalism. Did the enslavement of Africans affect the language-learning capacity of slaves in the homesteads and plantations of the New World and Indian Ocean? Was there really a break in the transmission of the lexifier? Does this suggest that only Europeans (including those who learned the lexifier in the colonies) could transmit the European language? What about the Creole children who were born during the homestead phase and spoke the colonial variety of the relevant European language as fluently as the European colonists? If there was a break in the transmission of the lexifier how did creoles manage to retain over 90% of their vocabularies from the lexifier? Is it really true that the bulk creoles' grammars are not from the lexifier? Where is the comparative evidence involving the relevant data that supports the conclusion? The work of Robert Chaudenson, that many Anglophone scholars have not read, tells us a whole lot about all this, although it does not answer all the questions. At present, we have many more open questions than definitive answers. I am shocked by the extent to which many/most linguists have remained wedded to 19th-century assumptions about the emergence of creoles and pidgins (my choice of this order is intentional), when the logic would be to continue reopening the books in the face new facts, especially regarding the history/histories of the contacts!

Since Sally Thomason relies so much on the comparative method, can it alone prove genetic kinship? If it does, why do we have to worry about convergence areas? Also, did creoles emerge faster than other languages? Isn't Haitian Creole as old modern French is, or Gullah as old as other American English varieties? Did it really take the ancestors of the Romance languages much longer to speciate from Latin? Cicero used to complain about how poorly Latin was spoken in the provinces!

Eric Vinyl said,

May 10, 2013 @ 4:29 am

@Jason

I'd love to know more about the usurpation of Police Motu by New Guinea Pidgin. I've been intrigued by Hiri Motu for some time, which, despite being an official language of PNG, seems essentially moribund. It was my understanding this had more to do with the role of Australia and English vis-à-vis PNG post-WWII, increased intermarriage, the shift of governmental administration and national identity following independence, etc.

Etienne said,

May 10, 2013 @ 2:50 pm

@Eric Vinyl:

Actually, it seems clear that Vulgar Latin is an outgrowth of Classical Latin. The Polish scholer Witold Manczak has repeatedly pointed out that there are no linguistic features in Vulgar Latin that require researchers to postulate some common "Old Latin" ancestor of Vulgar and Classical Latin. Rather, all Vulgar Latin features (leaving aside perhaps some items of vocabulary) appear to go back to Classical Latin.

@Salikoko Mufwene–

You speak of the "empirical weakness of creole exceptionalism", but without presenting linguistic facts or data. Very well. Indulge me here: I've a hypothetical and data-free scenario I wish to present to you.

Suppose a linguist showed that Tok Pisin shared features with English-based creoles. Suppose, furthermore, that said linguist also showed that *no other* variety of English, or indeed any Germanic language, living or extinct, shared these features.

Suppose, finally, that this linguist showed that this *same* set of features marked off pidgins and creoles from *all* other members of their "language families": that is to say, that this set of features is shared by (for example) Tok Pisin and Haitian, to the total exclusion of *all* non-pidgin, non-creole Romance and Germanic languages.

Would you -hypothetically speaking, of course- then accept that creoles cannot be anything other than nativized pidgins?

Salikoko S. Mufwene said,

May 12, 2013 @ 12:36 am

Etienne, you are being hypothetical. Those unsubstantiated hypothetical structural features that set creoles as a group apart from other languages, I don't know them. If you find one from the literature, bring it up and we'll discuss it. I could also imagine hypothetically that there is a population of humans that are particularly acrobatic and prefer to "walk" on their hands rather than their feet. While such a population might conceivably exist, especially in my fantasy, it has not been identified yet.

You say that I 'speak of the "empirical weakness of creole exceptionalism", but without presenting linguistic facts or data.' If you reread my posting, I ask several specific questions related to the socio-historical contact settings in which creoles emerged. If you answer most, if not all, of them affirmatively, then you have empirical evidence (provided by the actual history of the relevant population contacts) for creole exceptionalism. Otherwise, you are engaged in hypothetical historical/genetic linguistics.

Your comment about Vulgar vs. Classical Latin does not factor in variation in the Roman population. It's like every Roman spoke like Cicero or Julius Caesar. Ditto for the legionaries in the Roman army. I suppose one might also claim some day that nonstandard Englishes are outgrowths of standard English!

Etienne said,

May 12, 2013 @ 1:24 pm

Professor Mufwene–

Very well, allow me to give you a concrete example. To repeat a question I asked Michel DeGraff once (and to which he gave no answer: I am hoping you will): Haitian, and indeed all Romance creoles, lacks grammatical (as opposed to derivational) gender.

Romance languages, standard and non-standard alike, have grammatical gender. In fact, the *only* non-creole Romance varieties which lack grammatical gender are…Romance pidgins.

So: Since A- Romance pidgins and creoles share this feature, to the *total* exclusion of any non-pidgin, non-creole Romance variety, and since B-Pidgins can nativize, as the example of Tok Pisin makes plain, I conclude C-That Romance creoles are nativized pidgins.

My question (to DeGraff, and now to you) is the following: what other conclusion can be drawn from the *linguistic* evidence?

You mention socio-cultural settings. Well, to misquote a STAR TREK character: Dammit, Jim, I'm a linguist, not a historical sociologist!

That is to say, if the linguistic data unequivocally point to a pidgin past, as I believe is the case (see above), then it is up to non-linguists to adjust to what we linguists have discovered. Not the reverse.

It is for this reason that I cannot take the work of Robert Chaudenson seriously. On the basis of his *interpretation of the historical evidence, as opposed to the linguistic data* he concludes there cannot have been a pidgin when creole-speaking societies were founded, therefore French creoles cannot be nativized pidgins. QED.

Finally, on Classical versus Vulgar Latin: if indeed there was so much variation that the latter cannot descend from the former, would you mind giving me an example of a *linguistic* feature of Vulgar Latin which *cannot* go back to Classical Latin and *must* go back to some earlier ancestor?

Salikoko S. Mufwene said,

May 15, 2013 @ 4:23 pm

Etienne:

Just because Romance creoles (and I am glad you consider French creoles and the like from Portuguese to be Romance languages!) are alone in not having grammatical gender does not mean that they evolved exceptionally. The Romance languages themselves don't express grammatical gender the way Latin did, relying primarily on the ending of the noun within in declension class. I would not say this evolution makes the Romance languages exceptional or singular. As you must remember, creoles are not the only languages that lack grammatical gender.

You got it terribly wrong in wanting to be just a (historical) linguist and not a historical sociologist. The point is that you won't understand what is going on if you ignore the other relevant aspects of the subject matter. Also, your comment about Robert Chaudenson suggests to me that you are not familiar with his work or just did not understand it. He does not overlook the linguistic data but rather interprets it in light of the socioeconomic history that underlies the way things evolved. You must have missed or failed to understand my allusion to the relevance of history to determining whether a bottle is half-empty or half-full. The evolutionary interpretation of creole and pidgin data is far from being unequivocal. Please read some of our publications carefully about this issue. "Our" includes Robert Chaudenson, Michel DeGraff, Enoch Aboh, and myself (among a few others) on this. If you read colonial history carefully, you will find out that they leave very little room, if any, for the pidgin-to-creole evolutionary trajectory. Perhaps in a couple of years I will be reopening the books on this, in print, with specific documentation against this deeply entrenched myth.

At this point, I also feel that you and I may be talking past each other. I won't get to the Classical/Vulgar Latin question, because my time is limited. So, I'll say "mi taak don" (in an approximation of Caribbean English Creole). Thank you.

Etienne said,

May 16, 2013 @ 5:34 pm

Professor Mufwene–

So you know, because of your examination of the socio-historical evidence, that creoles cannot be nativized pidgins. Just as you know that Vulgar Latin cannot be a later, changed form of Classical Latin. This knowledge allows you to ignore all data which point to creoles being nativized pidgins or to Vulgar Latin indeed being an outgrowth of Classical Latin. How convenient.

The problem is this (you might want to sit down before continuing): as an interpreter of pre-modern socio-historical dynamics it is possible that you are wrong. Inasmuch as the linguistic evidence wholly contradicts your claims, I will trust said linguistic evidence and assume your claims are untrue.

I trust you won't take it personally: I assure you I have quite regularly ignored my own hunches and intuitions whenever they conflicted with observed facts.

The same criticism applies, incidentally, to the authors you have listed. None of them, to my knowledge, has presented any convincing *linguistic* evidence that the pidgin-to-creole scenario must be wrong.

All, indeed, are guilty of the same sort of PETITIO PRINCIPII which lies at the root of your own oeuvre. Namely, they assume the truth of the desired conclusion (that creoles are not nativized pidgins) and thereafter ignore contrary factual evidence.

The very fact that you did not know that Romance pidgins and creoles share a feature (loss of grammatical gender) which is wholly alien to all known non-pidgin, non-Romance varieties, is to my mind very telling. I could list a great many other such features. But it is obvious that all of them together would not change your mind. You already know the Truth: creoles cannot be nativized pidgins. Facts are irrelevant.

I will, instead of listing more linguistic features which point to creoles being nativized pidgins, encourage you to ponder Steven J. Gould's words: "Unbeatable systems are dogmas, not science".

You're welcome.

John M. said,

November 1, 2013 @ 7:08 pm

The educational system in Haiti has numerous problems, but the use of French, in and of itself, as a problem may be overstated (if it is even a problem).

Many countries around the world use a medium of instruction that is not the home language of students, and this ultimately does not seem to pose problems – the students simply become bilingual through immersion. This is the case in much of West Africa, where French is now very widely spoken, almost entirely due to public education. Compared to their West African counterparts, Haitians moreover have the built-in advantage of already possessing most of the vocabulary of French due to their knowledge of Haitian Creole. To say that "most Haitians only speak Creole," as is often repeated, is misleading due to this common vocabulary.

In any event, from what I understand, most Haitians who do graduate high school are bilingual in French/Creole. The problem is that most can't afford to go to school that long. Haiti's foremost educational problem is a lack of resources; most public schools in the country require students to pay tuition, because the government lacks the money to pay for schools itself. As Haiti is extremely poor, paying for education all the way to the end of high school is very difficult for many. This is the most essential issue to be resolved.

John M. said,

November 1, 2013 @ 7:14 pm

To continue, while educating students in Creole is not necessarily a bad initiative in the abstract, I have concerns that meeting the costs of translation and finding enough qualified, willing teachers (which is already a problem in Haiti, even with French, a more widely spoken language, as the language of instruction) are only going to further strain a system that already simply lacks basic resources. Haiti's first educational priority should be to ensure that every student can attend a public school; all other issues pale in comparison to that.