(South) Korea bashing

« previous post | next post »

Following up on these two recent posts:

- "Hate" (3/8/17)

- "No Japanese, South Koreans, or dogs" (3/8/17)

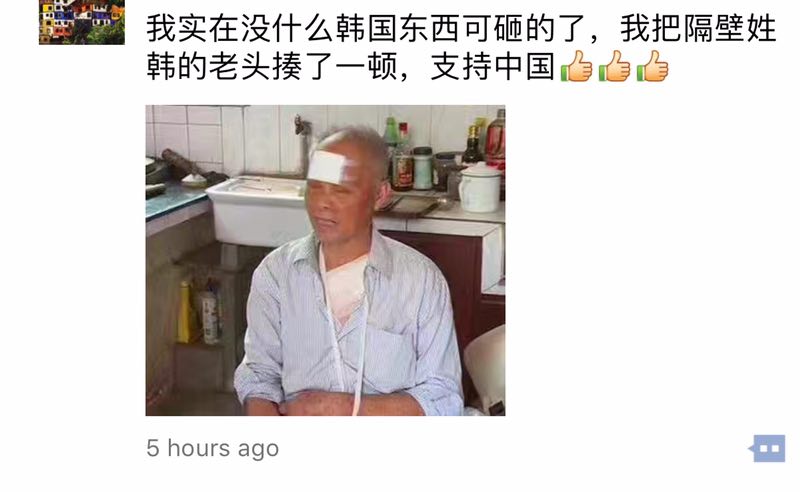

The Chinese characters above the photograph say:

Wǒ shízài méi shénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de le, wǒ bǎ gébì xìng Hán de lǎotóu zòule yī dùn, zhīchí Zhōngguó

我实在没什么韩国东西可砸的了,我把隔壁姓韩的老头揍了一顿,

"I really didn't have any (South) Korean things left to smash, so I gave the old guy surnamed Han* next door a beating to support China".

*[VHM: Hán 韩 was the name of an ancient state which existed from 403 to 230 BC in what is now Shanxi and Henan; it also forms part of the name of the modern country of (South) Korea — Hánguó 韩国.]

As explained in the earlier posts, Hánguó 韩国, in current parlance, refers specifically to South Korea. Hán 韩 is also an ethnic Hàn 汉 surname (don't get confused — different tones, different characters).

Of course, the above microblog post constitutes a kind of black humor, but South Koreans in China are receiving genuine threats and feeling concerned about their safety. The following is from one of China's most "authoritative" newspapers:

"South Koreans in China fearful as rumors about safety spread, ties worsen" (Global Times, 3/9/17)

Grammatical Notes

When I initially transcribed the long Chinese sentence above, I made a typo on the penultimate character of the first clause, mistyping 的 as 得. That's very easy to do, because they are both pronounced "de", are both very high frequency characters, and are both grammatical particles that properly occur in that position (between a verb and the clause / sentence final particle le / liao 了). But substituting de 得 for de 的 makes a world of subtle difference in the clause.

In fact, both clauses can roughly be translated as "I don't have anything Korean that I can smash". However, because of the different de 得/ de 的 and the different pronunciation and usage of le / liao 了, there is a significant disparity in the implications depending on whether de 得 or de 的 is used.

In "Wǒ shízài méi shénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de liǎo 我实在没什么韩国东西可砸得了, it means there is nothing Korean that I am able to smash, but the reason is unknown. Maybe all the Korean things the speaker owns are so important or so expensive that he / she cannot or dare not smash them. Or maybe all the Korean things the speaker owns are so huge and solid that he / she wouldn't be able to destroy them even if he / she tried to do so. In any case, "V de liǎo 得了" indicates that the subject of the sentence has the ability to carry out the action (verb). So, ”méi shénme 没什么 noun kě 可 V de liǎo 得了“ means "there is nothing the subject can verb". In this case, the speaker simply doesn't have anything South Korean around or left that he / she thinks he / she can smash, and we don't know the reason.

However, "Wǒ shízài méi shénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de le 我实在没什么韩国东西可砸的了, with de 的 instead of de 得, the clause means that I have smashed every South Korean thing at my disposal, so there's nothing South Korean left for me to smash. This pattern "méi shénme 没什么 noun kě 可 verb de le 的了" indicates "there's nothing left for the subject to verb".

Here are some example sentences employing the kě 可 plus Verb plus de 的 (kě 可 Verb de 的) construction, which is similar to the English expression "have something to do", or "doable", or "be worth doing".

Wǒ méiyǒu shénme dōngxi kě chī de 我没有什么东西可吃的

(“I have nothing to eat” or "I do not have anything that is eatable")

Zhèlǐ méishénme kě mǎi de 这里没什么可买的

("There is nothing to buy here" or "Nothing here is worth purchasing")

Wǒ xiànzài méishénme kě zuò de 我现在没什么可做的

(“I have nothing to do now”)

Thus, "kě 可 Verb de 的" actually makes the verb function either as a noun or an adjectival component in the whole clause / sentence. It is grammatically correct to say "Wǒ méiyǒu shénme kě chī de dōngxi 我没有什么可吃的东西" ("I don't have anything to eat"). The post-position of this adjectival component is for emphasis (something like "I don't have anything at all to eat" or "I really don't have anything to eat" or "I truly don't have anything that is eatable / worth eating").

So it's just as well that I made that typo (de 得 for de 的), since it has prompted me to expatiate upon the subtle nuances of the "kě 可 Verb de 的" construction, which is something I might not have done otherwise.

Speaking of subtle nuances, I have to account for one more part of the first clause of the original long sentence from the microblog post cited above, viz., le 了. That's called "change of state le 了". This is something I learned very early in First-year Mandarin, and it has stuck with me indelibly ever since. This "change of state le 了" implies that there is a new situation that is different from the one that existed before. Hence,

Wǒ shízài méishénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de 我实在没什么韩国东西可砸的

(“I really do not have any South Korean things to smash”)

BUT

Wǒ shízài méishénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de le 我实在没什么韩国东西可砸的了

(“I really do not have any more South Korean things to smash”)

These tiny, little grammatical particles in Sinitic languages exert an enormous influence in conveying the overall meaning of clauses and sentences that is disproportionate to their size. I will discuss their role in Cantonese, where they are even more numerous than in Mandarin, at greater length in a separate, forthcoming post.

[Thanks to Melvin Lee, Fangyi Cheng, Jing Wen, and Yixue Yang]

AntC said,

March 12, 2017 @ 4:01 pm

Thank you Victor. I made a typo on the penultimate character of the first clause, mistyping 的 as 得. That's very easy to do, because they are both pronounced "de", are both very high frequency characters, and are both grammatical particles that properly occur in that position …

Are these two pronounced exactly the same? And could either appear in exactly that context? Then can you be sure whoever originally wrote that microblog used the 'right' character?

Given the 'character amnesia' you write of so often, (and the ease with which even you can slip up), is it possible you're reading more subtlety into the message than was intended? Could it be more a sort of malapropism? (Or perhaps 'benapropism'.)

David Morris said,

March 12, 2017 @ 6:40 pm

So was the man Korean or Chinese, or isn't that the point? Is 'Han' a more common surname among Koreans in China than it is among Koreans in Korea? Even it if is, they must still be outnumbered by the Chinese 'Han's (the surname, that is, not the Han Chinese, obviously).

Anonymous Coward said,

March 12, 2017 @ 7:50 pm

David Morris: Good question! Han's are 0.86% among Han Chinese in Mainland China and 1.52% among citizens of South Korea, which stands as proxy for Korean-Chinese. So both of your hypotheses are absolutely correct. Note, however, that Han is not notably more common among ethnic Koreans than Han Chinese, so it doesn't carry any image of being particularly "Korean", unlike Kim/Jin (21.6% ROK, 0.31% Han PRC), Park/Piao (8.5% ROK, ~0% Han PRC), Choe/Cui (4.7% ROK, 0.28% Han PRC).

Anonymous Coward said,

March 12, 2017 @ 8:13 pm

A further caveat is that around 70% of Korean-Chinese originate from Hamgyŏng-do and Pyŏngan-do, both securely in DPRK territory, making the use of ROK citizens as proxy for family name frequency of Korean-Chinese somewhat inaccurate.

hanmeng said,

March 12, 2017 @ 9:10 pm

Re "change of state le 了": sad to say, I have heard both non-native learners of Mandarin but also even native speakers of Mandarin claim that le 了 marks the past tense.

Victor Mair said,

March 12, 2017 @ 10:24 pm

When I started studying Mandarin, we learned at least six or seven different functions of le 了. I think that teachers have now boiled them down and combined them into only two or at most three. Good teachers don't talk about a "past tense le 了". It is more accurate to refer to a "completion le 了". And that is different from the "change of state le 了".

Victor Mair said,

March 12, 2017 @ 11:42 pm

AntC posed some good questions about de 得 and de 的.

Yes, they are pronounced the same, but their functions are completely different. De 得 is a particle for marking verbal complements (resultative, degree) and de 的, by far the highest frequency morpheme in Mandarin, marks subordination, nominalization, and adjectivalization. Depending upon what the speaker wants to say, they will be thinking either of one or the other of these two "de" particles. Actually there is a third high frequency "de" particle, and that is 地, which some of my teachers, and consequently I myself, used to pronounce as "di", but now I think that almost everybody pronounces it as "de". This de 地 is used to form adverbs.

In the construction discussed above, "kě 可 V de 的 / 得 le / liǎo 了“, if the speaker is thinking of de 的, then the 了 that follows will be pronounced "le". If the speaker is thinking of de 得, then complementarity kicks in and the 了 that follows will be pronounced "liǎo".

As for whether the speaker / writer of the long, three clause sentence that began this post might not actually have intended de 得 instead of de 的, I asked several native speakers of Mandarin and they all said that, given the context, de 的 was clearly intended, and that it forms an attributive phrase. That is my instinct as well.

Simon P said,

March 13, 2017 @ 3:33 am

Regarding the 地 particle, I find this is very often written with a 的 in informal texts. Not sure about the frequency, but my impression is that it's slowly falling out of use.

flow said,

March 13, 2017 @ 4:56 am

Not sure I'm fully buying into the analysis of '…kědele' 可的了 vs '…kědeliǎo' 可得了. After all, it is the part written as 了 that is different in pronunciation between the two constructions, while the part written as 的 and 得 remains constant.

So on the face of it, shouldn't one postulate that there are two morphemes 'le' and 'liǎo' that happen to be written with the same character 了, and another, also quite multifunctional, morpheme 'de' that has the distinction of being writeable with two distinct characters 的 and 得 (or only one, 的, or indeed three, 的得地, according to who you ask)?

A comparable thing happens in German 'das' vs 'dass' (formerly 'daß'). A lot of discussion surrounds this ubiquitous word; the short story is that when 'das' is used as an article ('the') or as a relative pronoun, then it must be written 'das', but when used as a conjunction, it must be written as 'dass'. This is easy to get wrong, and although I have experience as a proof reader, I always double-check my dasses for fear of getting them wrong (and I certainly do, as—TIL—Goethe did).

Now my hunch is that, to a native speaker/listener/reader/writer, 'das' and 'dass' are psychologically the same entity, simply because they sound the same and can be used in very similar phrasal environments. Yes, I know you can easily test and show they're different: if you can substitute 'dieses/jenes/welches' into a sentence to replace 'das/dass', then it's the former, else the latter. This much is easy to demonstrate, but still: doesn't the presence of litmus testify to the distinction not being a natural, obvious one? Both Wiktionary and Paul's "Deutsches Wörterbuch" (p125: "'dass' … identisch mit 'das' … erst seit Mitte 16Jh [getrennt]") tend to emphasize the superficiality (i.e. mere-written-language-ness and historical recency) of the distinction. Is there a more principled stance of linguistics to this kind of situation? 'One' 'word' or 'two' 'words'?

Back to Chinese, from what I know the urge to separate older 的 into three distinct 的, 得, 地 would appear to be a 20th-century-grammarian's itch that is no older than that, but I may be wrong. But it's hilarious to observe how a language with thousands of distinct characters at their users' command ends up recommending a spelling that recycles 地 for an atonal particle (I always found that usage gross) instead of finding a more independant symbol for that role, while at the sime time writing 了 for both 'le' and 'liǎo', where alternatives like 瞭 for the latter can be and have been used.

In short, why not better write 可的了 vs 可的瞭, 可得瞭 and put the distinction where the distinction is?

John said,

March 13, 2017 @ 5:11 am

The three 'de's are pronounced differently in Cantonese, so there's no danger of them falling out of use or being written wrongly by someone who thinks in Cantonese, even if they are writing Mandarin or 'formal Cantonese'.

In informal or pure Cantonese 的 is replaced with ge, which I can't type as I have forgotten the pinyin, don't have CPIME or handwriting here, and can't be bothered to google for the character.

'deliao' is usually just 'duck' (dak1) in Cantonese.

@David Morris, it's like a white supremacist saying "I ran out of black people to lynch, so I beat up my neighbor, Mr. Black."

Victor Mair said,

March 13, 2017 @ 8:25 am

There are actually four particles pronounced de in Mandarin: 的得地底. There are many reasons why they cannot possibly all represent the same Sinitic morpheme. Here I will list the more salient points:

1. As is true of many particles in Sinitic languages, they are usually derived through a process of bleaching, and the traces of their original semantic content may often be seen, however dimly, in their earliest occurrences (e.g., dé 得 ["attain; obtain; get"]).

2. All four of these MSM de appeared — with multiple, though usually related, functions — in vernacular texts dating to the Song, Jin, and Yuan periods (i.e., Late Medieval [or Early Modern, depending on your historiographical and theoretical politico-economic outlook]), and in some cases already by the Tang period (squarely in Medieval times).

3. In Middle Sinitic, they all had different pronunciations, which are reflected in their Cantonese pronunciation (John was so right to mention that, and I am grateful to him for having done so). In Middle Sinitic, 的 was pronounced dek (cf. MSM dì) and originally meant "target" and a few other things. During the course of the last thousand years, it developed as many as fifteen different, identifiable functions as a particle, for which see Hànyǔ dà cídiǎn 汉语大词典 (Unabridged Dictionary of Sinitic), 8.251ab.

Given just this highly abbreviated account of the meanings, sounds, and functions of 的得地底, it would be a travesty of historical linguistics if we were to assert that there is only a single MSM de morpheme.

Similarly, although multiple grammatical functions are represented by the character 了, the very fact that it is still read in two distinct ways (le and liǎo), even in Mandarin with its reduced inventory of sounds, is a sure indication that a variety of different sources have collapsed into this one character. Many articles and dissertations have been written on the historical background of 了. It would be an even more formidable task to straighten out the historical background of Mandarin de.

flow said,

March 13, 2017 @ 9:08 am

@VHM thanks for the clarification. So I was wrong about 的得地(底) being a more recent distinction.

Still, I feel that adducing evidence from another (related) language (Cantonese) and historical usage does not quite answer the question whether for 'average' native speakers with no knowledge of historical linguistics these words are same or different. Which is why I brought up the subject of G das/dass; I'm perfectly fine with saying those are two are "different words", and I can suggest some reasons for that, yet the fact that the different spellings keep being reliable sources for misspellings taints that picture somewhat (likewise, we could demand that e.g. 'um' should be spelled differently in "um drei Uhr" (at), "um zwei Stunden" (about), and "um es zu genießen" (in order to); that no-one quibbles over *these three* seems to be more related to present orthography rather than grammar or history).

"it would be a travesty of historical linguistics if we were to assert that there is only a single MSM de morpheme"—right, but what about today? I'd imagine that, for example, the possibility to read 可的了, but not 可得了 as di (with some tone) strongly suggests the existence of two distinct morphemes. BTW, all of 的地底 can be read as dì/dǐ, while 得 is on record (zdic.net) with dé, děi, de. Are there people who actually say 他走得很快 with di (I'd guess not)? Lastly, I share Simon P's impression that "地 […] is very often written with a 的 in informal texts". At what point of merger is there only one left? Does that question even make sense?

liuyao said,

March 13, 2017 @ 12:42 pm

As native speakers, such grammatical issues don't come across our minds. I'd think the sentence was intended to say "de le 的了", and if I were to mean "de liao 得了" I could/would say "我实在没什么韩国东西可砸得了的了" (a little awkward to read, but natural to one's ear if said with the right cadence.)

It feels like 的了 is more a compound word, whatever it means.

Simon P said,

March 15, 2017 @ 1:30 am

@flow: Regarding my impression of the conflation of 地 and 的, this is only true of Mandarin speakers. A Cantonese speaker would never conflate the two, and as long as written standard Chinese is used by people speaking both Mandarin and Cantonese, we cannot say that the two have merged. It's a written distinction, and the written language can be read in Cantonese.

flow said,

March 15, 2017 @ 5:48 am

@Simon P—aren't you mixing up *several* levels here? Sure there are people speaking other languages than Mandarin that keep similar / related morphemes separate, sure they can read or write a written idiom that purportedly bridges the differences between the vernaculars—but how does that affect the state of affairs in Mandarin?

flow said,

March 16, 2017 @ 5:59 am

(probably nobody is watching this thread anymore, but for what it's worth): Today there happened to pop up a question on Chinese Stackexchange (http://chinese.stackexchange.com/questions/23092/in-these-2-sentences-does-%E5%BE%97-have-the-same-function) entitled "In these 2 sentences does 得 have the same function?".

There's a novice user 'hao.li' who offers some insight. Now, pls bear with me and this user: their answer is not really to the point of that discussion and their English isn't the best. The insight offered ("I don't need grammar (for Mandarin) because I (just) have to think (of something and out comes) every sentence") probably shows that the speaker has not concerned themselves much with language studies in a formal context. OTOH it seems to be candid when they say:

"i know this forum today,so i sign up a account and learn english instead, fo me , i thinks chinese grammar is stanger, because, for us, i need not any grammar, so i think every sentence, i noly use "的" is ok, because, i never use "得 地" for a long time"

So here's a practical example for what I suggested earlier: Just an average language user who states that in their usage, 的 has come to stand in for 得 地 as well. The reasoning is logically circular ("I only use 的 because I haven't been using 得 地 at all for a long time"), but the sentiment is there and valid.