"Dog" in Japanese: "inu" and "ken"

« previous post | next post »

This post intends to take a deep look at the words for "dog" in Japanese, "inu" and "ken", both written with the same kanji (sinogram; Chinese character): 犬.

I will begin with some basic phonological and etymological information, then move to an elaboration of the immediate cause for the writing of this post, observations from colleagues, and a brief conclusion.

For those who are unfamiliar with Japanese, most kanji (Sinograms) have at least two quite different pronunciations, an on['yomi] 音[読み] (Sino-Japanese reading) and a kun['yomi] 訓[読み] (native reading). In the case of 犬 ("dog"), the former is ken and the latter is inu. They both mean "dog". The underlying question that prompted me to write this post is when to use which. And that came in the form of a long message from Nathan Hopson, which I quote here:

In recent years, Japanese television has embraced a role as cheerleader for “Cool Japan,” producing a mess of self-congratulatory paeans to Japan in the form of shows about:

a) Japanese people, culture, and businesses succeeding in the world, or

b) how much foreigners (especially, but not exclusively Westerners, i.e. gaijin) love those same Japanese people, culture, and businesses

The segment I saw recently on TV Aichi’s どうぶつピース!! (Dōbutsu Pīsu!!) about Japanese dogs shows how far this goes. Yes, the dogs of war have become the dogs of culture wars. And the dogs of failed international political manipulation, according to this BBC article about Japan’s attempt to ingratiate itself with Putin by giving him a second dog ahead of his visit and talks about finally signing a peace treaty and the Japanese pipe dream of getting Russia to “return” four northern islands.

Before going any further, it’s worth noting that, in English, the title, “Animal peace!!” would be properly punctuated, “Animals, ‘Peace!’” In other words, it’s basically, “Hey animals, say ‘Cheese!’” The subtitle is “Super-cute images one after another!” Television is learning, and plagiarizing, from YouTube.

Anyway, the segment in question was one of several on the program that’s a story rather than a glorified YouTube video. It appears to be part of a longer series of stories about the popularity of Japanese dogs in the world. Television would have its captive audiences believe that Akitas and Shibas are growing popular in the world, and there’s an implicit link to Japan’s “Gross National Cool” and the whole “Cool Japan” phenomenon. This is emphasized by the Japanese names that Western owners choose for their dogs, their stories of falling in love with Japan and/or Japanese culture (usually manga and anime), etc. This is precisely the sort of thing that’s driven me to ignore Japanese TV as much as possible recently.

But my interest was piqued when my wife mentioned that she was rather suddenly bothered by something that had been nagging at me for a while now.

When I learned Japanese twenty years ago, Akitas (秋田犬) and Shibas (しば犬) were most definitely “Akita ken” and “Shiba ken,” both using the sinicized reading (on yomi) for the character for dog (犬). But in recent years, I’ve been hearing broadcasters use the “nativized” reading (kun yomi), “inu” for both.

So when my wife mentioned that she was feeling the same uneasiness about “Akita inu,” I decided to figure out what’s going on here.

First, the English sources.

In English, things are relatively simple for the Akita, because the breed name doesn’t include either inu or ken.

The American Kennel Club, which describes the breed as “Dignified, courageous, and profoundly loyal,” officially recognized the Akita in 1972, though breed standards in Japan date to the 1930s. The AKC website adds, “The ‘inu’ that is sometimes added to the name simply means ‘dog.’” There is no mention of the “ken” reading.

As far as I can tell, The Akita Club of America does not take a stand on the issue.

One important tidbit that both of these organizations (and Wikipedia) note is that, as the Akita Club puts it, “The Akita is one of Seven Breeds designated as a National Monument in his native country of Japan.”

So on to the Japanese sources.

The Agency for Cultural Affairs, which manages such designations, is unambiguous: the reading in the Agency database (Japanese only) for Akitas is あきたいぬ (Akita inu), and “ken” is nowhere to be found. So officially, inu it is.

The website of Odate City, the dog’s ancestral home (it was previously referred to as the Odate dog and added to the list of National Monuments as the Akita in 1931), is also firm on this point.

What of other Japanese native dogs?

The Shiba is another Japanese dog popular outside Japan, and it is also referred to in the media using inu rather than ken. The Agency for Cultural Affairs agrees, though I have to admit this weirds me out a bit, too.

So what about the other five dogs registered as National Monuments? (And what about the word “monument” here…?) Well, I just about threw my hands up and walked away when I put the database results into a list:

Inu

秋田犬 (あきたいぬ) Akita

柴犬 (しばいぬ)Shiba

越の犬 (こしのいぬ) Koshi or Koshino (extinct)

Ken

甲斐犬 (かいけん) Kai

紀州犬 (きしゅうけん)Kishu (Kishū)

土佐犬 (とさけん)Tosa (distinct from the Tosa fighting dog, apparently)

北海道犬 (ほっかいどうけん)Hokkaido

FWIW, the Japanese dog fan community site nihonken.org (note “ken!!”) lists:

Akita (秋田犬)

Hokkaido Inu (北海道犬)

Shiba Inu (柴犬)

Kai Ken (甲斐犬)

Kishu Ken (紀州犬)

Shikoku Ken (四国犬)

Well, as you might expect, it turns out that my wife and I are not the only Japanese speakers bothered by this. A quick Google search yields dozens of questions like this one (in Japanese) in online Q&A informational forums like Yahoo! Japan’s Chiebukuro (“Adviser”) alluding to confusion or frustration with this choice.

So why is it that the government agency in charge of cultural affairs and the media persist with the inu pronunciation?

Turns out, NHK has an answer. And yes, it’s an answer to a perplexed viewer’s question. And yes, I felt vindicated by this. But then I saw the date: 2001. So this has apparently been “a thing” for much longer than I realized. Feelings of vindication melted away….

Japan’s public broadcaster keeps a manual (ことばのハンドブック, Kotoba no handobukku) for just such questions of linguistic usage. So when a viewer / listener asked about NHK’s policy on the discrepant readings of 犬, the handbook came to the rescue with a general non-answer:

“The readings are decided based on consideration of both concerned organizations (such as local preservation societies) and customary common usage.”

But the specifics are actually quite interesting:

“For instance, in its home region, 秋田犬 is traditionally referred to as ‘Akita inu’ … However, a February 1990 poll of Tokyo male and female residents sixteen years old and older revealed that 95% pronounced this name ‘Akita ken.’ For this reason, NHK decided to add ‘Akita ken’ to the traditional ‘Akita inu’ as acceptable for use in broadcasting.”

The answer continues with a list of NHK’s accepted pronunciations, which differs from the Agency for Cultural Affairs:

Inu

しば犬 [×柴犬] Shiba

(Note that the “x” means that NHK does not accept the kanji 柴 for the dog breed, though it is used both commonly and by the Agency for Cultural Affairs)

Ken

甲斐犬 Kai

紀州犬 Kishu

北海道犬 Hokkaido

カラフト犬 Karafuto

Either

秋田犬 Akita

土佐犬 Tosa

This left me wondering about how and why “Akita ken,” and for that matter “Shiba ken,” had become so commonplace. My assumption is that it’s because of parsing issues. When treated as a suffix for the preceding word, “-ken” as in Nihonken (Japanese dog/s), it’s treated as one character of a longer Sinitic compound. When treated as a separate word, as in “Akita + dog,” then inu makes sense. However, that’s a harder sell given normal Japanese parsing patterns.

Any insights? And what about analogous examples in other languages?

Nathan's observations might very well stand as a substantial Language Log guest post on their own, and indeed they are, but I'm adding a few things below to supplement all the good information that he has provided.

The pronunciation of 犬 (犭when used as a radical on the left side of a character) in MSM is quǎn, in Cantonese is hyun2, in Hakka is khién / khián, in Southern Min is khián, in Wu is qyoe2, in Middle Sinitic is /kʰwenX/, and in Old Sinitic is /*[k]ʷʰˤ[e][n]ʔ (Baxter-Sagart) or /*kʰʷeːnʔ/ (Zhengzhang).

(There's a quite different word for "dog" in Chinese, viz., gǒu 狗, but I will leave that for another occasion, just as I will not discuss the two main words for dog in English, "dog" [PIE root unknown] and "hound" [has a PIE root], though others may wish to say something about the Chinese and English pairs in the comments.)

Thus we know very well where the character 犬 and the pronunciation "ken" come from, but where does "inu" come from? I have the same sort of question about all Japanese pairs of on and kun readings, so it will be a treat for me to look intensively at this one particular case.

I'm the proud owner of Yamanaka Jōta 山中襄太, Kokugo gogen jiten 国語語源辞典 (Etymological Dictionary of the National Language) (Tokyo: Azekura Shobō 校倉書房, 1976, 1993 [4th ed.]). On p. 78a, the author lists the following words for "dog" in Tungusic topolects of Manchuria: ina, inau, inai, inaki, inda, and nenda.

I cannot help but think that these Tungusic words and Japanese "inu" are somehow related. Roy Andrew Miller famously believed that Japanese and Korean were members of the Altaic language group. The consensus view of professional linguists, however, is that there's not even a well-established Altaic language group, much less one that includes Korean and Japanese. See J. Marshall Unger, "Summary report of the Altaic panel", in Philip Baldi, ed., Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology (Berlin: Mouten de Gruyter, 1990), pp. 479-482.

The Manchu word for "dog" is "indahun". I have a hunch that "hun" is some sort of suffix. See the remarks of Juha Janhunen and Jichang Lulu below.

Comments by historical linguists and philologists

Linda Chance:

At first I thought that this should be an easy answer: in compounds in which the character 犬 follows a name, it should generally be properly inu, since names would tend to be kunyomi-based, but readers tend to find it difficult to decide whether a reading of a name is kunyomi (calling for the kunyomi inu) or onyomi (calling for the onyomi ken). The Nihon kokugo daijiten from Shôgakukan lists only Shibainu for 柴犬. It favors Akitainu, although it also lists Akitaken as an alternate for 秋田犬. For 日本犬, Nihonken is the main entry, although Nipponinu is an alternate (I'm glad we're not touching on Nihon vs. Nippon). I wasn't really aware of a chronology for the bifurcation, but it would seem to be recent.

NHK has an answer to the query 'is it inu or ken?' online. They say that in their practice of the moment, some compounds are only read XXinu (e.g. Shibainu), some are only read XXken (e.g. Kaiken, Kishûken, Hokkaidôken, Karafutoken), and some are read either way (e.g., Akitainu/Akitaken, Tosainu/Tosaken). They explain that the official name of the Akita breed is Akitainu, according to the locally-based preservation society (Akitainu hozonkai), but a 1990 survey of males and females over sixteen in Tokyo found that 95% say "Akitaken." So the choice depends on the context. https://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/summary/kotoba/gimon/079.html

I have heard that the Nihonken hozon-kai 日本犬保存会 (Japan Dog Preservation Society) changed its reading from inu to ken twenty-five years ago, but I cannot confirm. If I had to guess, I would place the change about then.

John Whitman:

On the face of it, it seems like a typical on/kun division of labor to me. Yamato words are not good for compounding with proper names, so parallel to koinu 子犬 ("puppy") vs. Akita-ken 秋田犬 you get koushi 子牛 but Wagyū 和牛.

Alexander Vovin:

In Modern Japanese the normal word is native Japanese inu. Sino-Japanese ken occurs mostly in idiomatic expressions like ken-en no naka 犬猿の仲: the relationship between a dog and a monkey, which is an idiom for the relationship between irreconcilable enemies.

Jim Unger:

Well, ken is the usual Sino-J reading for 犬 and inu is its usual J gloss. Both denote 'dog', but the connotations of inu used as a free noun differ from its use in compounds (inu by itself can mean 'spy' too). Ken cannot be used as a free noun; it only occurs in compounds.

Juha Janhunen:

Sino-Japanese ken is today normally used in the sense of dog breed, e.g. ainu ken 'Ainu dog' or akita ken 'Akita dog'. Inu is the regular word when used alone, or also in some fixed expressions like koma inu 'Korean dog' = the Chinese mythical dog-lion hybrid. The word inu has no generally accepted etymology but has been compared with Tungusic nginakin 'dog'. It can hardly be connected with the Eurasian kyon-kywen > ken-quan 犬 etymon, which is also present in Korean gae and Ghilyak kan/ng. [VHM: Korean gae reminds me of Sinitic gǒu 狗.] Manchu indahun corresponds exactly to Ewenki nginakin. The Proto-Tungusic shape would have been *ngïnda-kun, with *-kun (> Ewenki -kin) apparently as a suffix but with no specifically identifiable meaning – perhaps diminutive.

Jichang Lulu:

Indahūn (from older indahon; Jurchen maybe *indahu) is Manchu for 'dog', and the -hV(n) part would look like some sort of suffix since elsewhere in Tungusic there are dog words without it (Oroch inda). But also with something resembling it (something like ninakin in Evenki), meaning the suffix isn't necessarily exclusive to Manchu. The elephant in the room is of course the Japanese and there have been attempts to link these Tungusic dog words to it.

Pamela Kyle Crossley:

Manchu for dog is “indahûn”. Vaguely like Japanese inu, huh? As for other Tungusic languages, I don’t know. Manchu is certainly not borrowed from Turkic or Mongolian, which have words like “ köpek” and "nokhoi" for dog. Daniel Kane (Kitan language and script) thought Kitan might have been ni.qo (Liáo shǐ guóyǔ jiě 遼史國語解 ["Explanation of the National Language in the Official Dynastic History of the Liao Dynasty]) gives the Chinese transcription as niehe) or something close, and gives “it” as Old Turkic.

Daniel Kane (responding to Pamela Crossley's note on ni.go being the Kitan word for "dog"):

Yes, more or less, but like most Kitan words, there is a sort of fuzziness as one tries to balance the Kitan script version, the Chinese transcription (Liaoshi [official history of the Liao Dynasty] usually) and various forms of Mongol. In this case we are lucky we have several sources, but still they do not jell exactly. I think ni-qo is as good as any – about 70% likely = which in Kitan is pretty high!

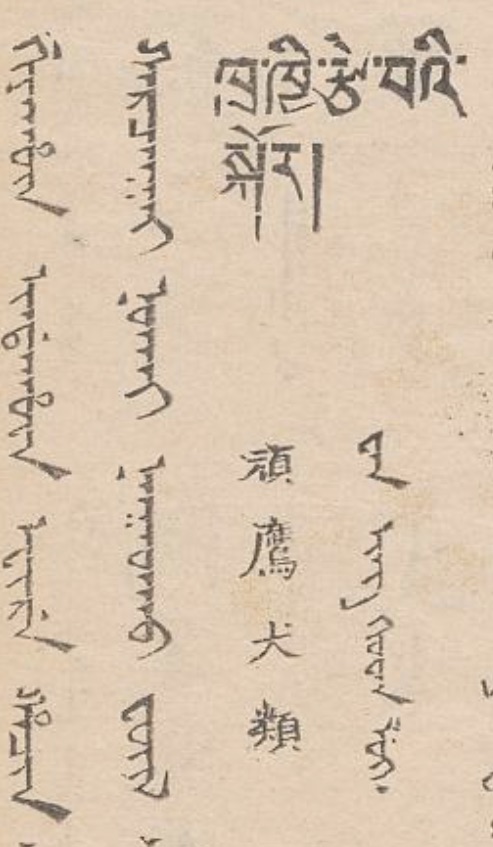

Here is a group of entries from the Sìtǐ hébì wénjiàn 四體合壁文鑒 (Four-script combined textual mirror printed during the Qing / Manchu Dynasty (provided courtesy of Pamela Crossley):

The entries in this section all mean what the Chinese means:

Chinese: wán yīng quǎn lèi 頑鷹犬類 ("playing with falcons / eagles and dogs"), where wán 頑 ("obstinate: stubborn; recalcitrant") = 玩 ("play; enjoy; have fun")

Tibetan: khra khyi rtse ba'i skor ("about / concerning / pertaining to the play / games / enjoyment of hawks and dogs") — hunting with falcons and dogs

khra=hawk, khyi=dog, rtse ( or brtse)=play/game, skor= about/around

Manchu: giyahvn indahvn efire hacin ("the category of sporting with falcons and dogs")

Mongolian: qarcaghai noqai naghadqu jüil ("section / part [about] playing [with] hawks [and] dogs")

The Manchu to the right of the Chinese gives Manchu phonetic glosses for the Chinese phrase.

Two final notes on the history of the word quǎn / inu / ken 犬 ("dog") in East Asia:

- I could not find this kanji / hanzi in John R. Bentley, ABC Dictionary of Ancient Chinese Phonograms (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2016).

- Axel Schuessler, in his ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007), p. 437, notes that this word survives in Min topolects, but has been replaced by gǒu 狗 in most of the others.

[Thanks to Steve Wadley, Leonard W.J. van der Kuijp, Douglas Duckworth, Elliot Sperling, Matthew Kapstein, Nathan Hill, Gray Tuttle, Bob Ramsey, and David Prager Branner]

Mara K said,

December 18, 2016 @ 12:15 am

I don't think I knew that "inu" meant "dog." When I see pictures of Shibas online (usually in the form of "doge" image macros), English-speaking posters call the breed "shiba inu," which is I guess like saying "corgi dog."

Then again, English kind of has that, or used to. "You ain't nothin' but a hound dog," anybody?

J.W. Brewer said,

December 18, 2016 @ 12:38 am

If you look at this lengthy list of (English) names of dog breeds officially recognized by the AKC, you will see that some do, in fact, have "dog" or "hound" (or compounds including -hound) as part of their names. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_dog_breeds_recognized_by_the_American_Kennel_Club

The vogue in some Western/gaijin quarters for akitas is not a particularly recent phenomenon. Lou Reed's 1983 song "High in the City" (about the Manhattan of that era) includes the lyric "Let's not walk down Sutton Place / You know everybody there's got an Akita."

Jim Breen said,

December 18, 2016 @ 1:34 am

I was going to comment that "ken" can't be used as a free-standing noun for "dog", but I see Jim Unger has already pointed that out.

The Japanese dictionaries are all over the place as to whether 秋田犬 is "akitaken" or "akitainu". For the major Japanese domestic dictionaries we see:

– 広辞苑 (Kõjien): akitaken is the main entry and akitainu is an entry cross-referenced to it.

– 大辞林 (Daijirin): only has akitainu.

– 大辞泉 (Daijisen): also only has akitainu.

For the Japanese-English dictionaries:

– Kenkyusha New JED (online supplement): akitainu is the main entry, and akitaken cross-references

– ルミナス (Luminous): akitaken is the main entry and akitainu cross-refererences.

And so it goes. FWIW あきたけん (akitaken) is about 5 times more common on the WWW than あきたいぬ (akitainu).

David Morris said,

December 18, 2016 @ 1:58 am

Nathan was certainly dogged in his research.

Maude Vuille said,

December 18, 2016 @ 3:27 am

I lived over three years on Awaji Shima in the early 90s, いなか at its best, and adopted with my roommate a stray, white Shiba-inu. -ken wasn't used conversationally, and everyone asked about our "Shiba-inu", or Inu-chan, as we named him. As I spoke Japanese and my roommate didn't, I was horribly embarrassed by its name, and would have jumped on the opportunity to call him Ken-kun had Shibaken been commonly used.

We call them Shiba-inu in French as well.

The elephant in the room is the quality of televised mainstream entertainment in Japan as represented by variety shows and certain types of "documentaries". That hasn't changed apparently. I feel for Mr Hopson.

Cool Japan has been a niche for decades, and 25 years ago オタク (otaku) were isolated youths who had not gotten out of their bedrooms in months/years. What a mix of social evolution and marketing!

One thing hasn't changed: the above show would never be called どうぶつ平和 (doubutsu heiwa).

Chas Belov said,

December 18, 2016 @ 4:48 am

@Mara K: There's Bassett hound.

AG said,

December 18, 2016 @ 7:25 am

I just lived in Japan for 5 years & as an English speaker with linguistic curiosity but no training in Japanese, & who had a mostly English-speaking workplace – I never even heard any dog-related words pronounced "ken". Only "inu". Dogs are inu. Puppies are ko-inu. Obviously there must have been a lot of "ken" floating around but it never registered with me. Just an observation on how predominantly inu-centric the foreigner's experience in Japan can be.

David Marjanović said,

December 18, 2016 @ 8:12 am

Ah, but that's 26 years old! A lot has happened since then…

…though we're no closer to a consensus than we used to be. I'll only mention An Etymological Dictionary of Altaic languages by S. Starostin, A. Dybo & O. Mudrak, Brill 2003, total of 2096 pages; despite its recent date, a few of its sources are already outdated, and it's very controversial for a variety of reasons.

ouen said,

December 18, 2016 @ 9:21 am

does 犬 really survive in the min topolects? i don't know about Fujian or SE Asia, but in Taiwan i'm fairly sure the more commonly used word used for dog is kau which sounds much closer to 狗 to me. i'm not a native speaker though so i could be wrong.

Pamela Crossley said,

December 18, 2016 @ 10:11 am

reminiscent of our earlier email chat regarding "hound," sort of looks like a native word coexisting with a continental inmport. still musing on the relationship betweeen DNA vectors and (loan)words for "hound" and "dog." pretty interesting, in that it is still unclear to me whether the animal and the word for the animal were really traveling together.

Lazar said,

December 18, 2016 @ 10:48 am

The various-language Wikipedias are an inconsistent mess here: English, for example, has Akita (dog) and Shiba Inu for article titles.

Ted Bestor said,

December 18, 2016 @ 11:56 am

Studying Japanese in Tokyo in the 1970s, I remember being told a joke, that played on a pun.

Atama ga ii inu wa, doko de benkyo shimasu ka?

drum roll here please

Akita Ken-ritsu Daigaku.

badda bing!

Mara K said,

December 18, 2016 @ 12:08 pm

@Ted Bestor

And for the benefit of those who didn't study Japanese, and only recognize "Akita Ken" in all of that, what does it mean?

Jon W said,

December 18, 2016 @ 12:31 pm

@Mara K,

If your head is a dog, where do you study? Akita Prefectural University.

The joke, such as it is, derives from the fact that 秋田県 (Akita prefecture) and 秋田犬 (Akita dog) can both be pronounced Akita ken.

Jon W said,

December 18, 2016 @ 12:33 pm

Oops — I missed the いい in the riddle. So the joke should be: "Where does a smart dog study? Akita Prefectural University." That's a somewhat better joke.

Amy Stoller said,

December 18, 2016 @ 12:33 pm

As I speak no Japanese nor any Chinese languages, I can’t add much to the learned commentary. On the anecdotal front I can contribute a little, I think.

When I was a little kid, poodles were often called poodle dogs, and collies were called collie dogs. I don’t know if this was only the way children or those speaking to children referred to them. It may have been a local NYC thing—I really have no idea. I haven’t heard these in years, but I remember it clearly. Does anyone else remember this, or something like it?

Hounds are a particular group of canine breeds, and in US kennel-club and dog-show circles at least, many hunting dogs are named [Type] Hound: Foxhound, Basset Hound, Bluetick Coonhound, etc. As a group they are called Hound Dogs.

I doubt my dad and his partner were especially aware of kennel-club naming conventions when they wrote Hound Dog. Jerry was looking for a “clean” euphemism for gigolo, and that’s what he came up with. http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/leiber-stoller-rolling-stones-1990-interview-with-the-songwriting-legends-20110822

Mara K said,

December 18, 2016 @ 12:38 pm

@Jon W–then the joke works in English too!

jick said,

December 18, 2016 @ 2:29 pm

I believe Modern Korean gae 개 (dog) is from Middle Korean gahi 가히. So, the similarity with 狗 might be just coincidence.

Mr Punch said,

December 18, 2016 @ 4:23 pm

@ Amy Stoller: From my childhood ('50s, eastern New England) I remember "collie dog" as common usage, and I think "boxer dog"; poodle, beagle, etc. stood alone. (German shepherds were sometimes referred to as "police dogs.")

Lazar said,

December 18, 2016 @ 5:08 pm

@Amy Stoller: I haven't encountered those, but I have similarly wondered at "tuna fish".

cameron said,

December 18, 2016 @ 5:35 pm

@ Amy Stoller: "poodle dog" is probably not a New Yorkism. I associate that expression with the hokum blues classic "Let Me Play with Your Poodle", originally recorded in 1942 by Tampa Red, who was not a New Yorker.

Jean-Michel said,

December 18, 2016 @ 6:44 pm

@ouen: 犬 appears to have been supplanted by 狗 in Southern Min, but it's still used in Eastern Min, pronounced as /kʰɛiŋ/ in Fuzhou (I see contradictory information on the tone).

maidhc said,

December 18, 2016 @ 6:52 pm

http://www.historysmith.com/tales_lost_poodledog_01_part1.html

B.Ma said,

December 18, 2016 @ 7:00 pm

In Hong Kong, 犬 is often seen on "no dogs allowed" signs although I never hear it in speech.

狗 is 구 in Sino-Korean but according to my Korean friend, it is only used in 成語 (seong-eo / chengyu / idiomatic expressions) and the native word 개 is used in all other circumstances.

Coby Lubliner said,

December 18, 2016 @ 7:13 pm

How about a similar discussion of "yama" and "san"?

J.W. Brewer said,

December 18, 2016 @ 7:19 pm

A quick dive into google books reveals e.g. a one-time establishment in Washington D.C. called the Poodle Dog Cafe (where the young Duke Ellington had a job as a soda jerk in 1913) and a geographical feature on the other side of the country in Washington state named Poodle Dog Pass. I doubt there are varieties of AmEng where "poodle dog" rather than bare "poodle" is obligatory, and I don't know how much of a pattern there is in variation. It could well be influenced by prosodic considerations in particular contexts.

SO said,

December 18, 2016 @ 7:31 pm

Re: "I could not find this kanji / hanzi in John R. Bentley, […]"

His dictionary actually does contain an entry for 犬, at least sort of — on p. 182 you'll find an entry for 喚犬 /ma/ (as only one example from a set of several animal-related digraphic phonograms attested in the Man'yōshū; others include 追馬 /swo/, 馬聲 /i/, 蜂音 /bu/ etc.) which occurs twice in the Man'yōshū (in poem XI/2645 as mentioned by Bentley, as well as in XIII/3324).

For reasons unknown, however, Bentley does not have an entry for 犬 /ma/ (likely short for and in allusion to 喚犬 as above) which is likewise found several times in the same collection, always to write the syllable /ma/ in the same word maswokagami 'clear mirror' (see poems XI/2810, XII/2980, XII/2981 and XIII/3250).

But that's not too surprising as Bentley's dictionary actually lacks entries for quite a number of well-attested phonograms, leaving a substantial number of other problems aside here. For instance there is also 犬 /nu/ or rather 犬 /(i)nu/ as attested in the spelling 三犬女 /mi-(i)nu-mye/ for the place-name Minumye (in poems VI/946 and VI/1065) which didn't get an entry either — incidentally Bentley mentions both attestions on p. 221 in his entry for 女 /mye/, so he must have been aware of its existence nevertheless. And maybe 汶 /minu/ in the variant spelling 汶賣 used to render the same place-name was not "ancient" enough to be included as well in the dictionary? (Its only found as late as the 927 Engishiki, even if the spelling as such is most likely older, just as other ones found in the same source are.)

Finally, for what it's worth: the Old Japanese word inu is also attested in the Man'yōshū, even in a straightforward phonographic rendering, namely as 伊奴 /i-nu/ in poem V/886.

Jean-Michel said,

December 18, 2016 @ 7:34 pm

狗 is 구 in Sino-Korean but according to my Korean friend, it is only used in 成語 (seong-eo / chengyu / idiomatic expressions) and the native word 개 is used in all other circumstances.

犬 (견 gyeon) also survives in some fixed expressions, like 犬儒 (견유 Gyeonyu) "Cynic" (the Greek ones–the Greek-derived 키니코스 Kinikuseu is also used but turns up fewer results on Google).

Jean-Michel said,

December 18, 2016 @ 7:36 pm

Sorry, 키니코스 is Kinikoseu.

Steven said,

December 18, 2016 @ 10:29 pm

I live in downtown Vancouver, a city with a fairly sizeable Japanese population comprised of permanent residents as well as students studying English on a short-term basis. I meet many Japanese speakers while walking my two Shibas, and I've only ever heard them referred to as Shiba KEN. (Frequently followed by squeals of "かわいいいいいいい !!!") But English speakers — at least the ones who recognize the breed — will call them Shiba INU.

(Many, however, don't recognize the breed at all:

"Hey, it's that dog from the movie!" – "No." (ハチ公 was an Akita.)

"Is that one of them [sic] dogs that don't bark?" – "NO."

"OMG are those FOXES?!?!?" – [sigh])

What I find interesting, though, is that many people mispronounce the name of the breed as ShibU Inu. How would one describe that phenomenon in linguistic terms? Some sort of phonological assimilation? Regressive metaphony?

Jichang Lulu said,

December 19, 2016 @ 8:55 am

Slightly off the canine topic: the Qianlong-era 四体合璧文鉴 Siti hebi wenjian mentioned in the post is one of a number of polyglot dictionaries produced during the Qing. I think most of its Manchu-Chinese translations come from earlier dictionaries, such as the 御制增订清文鉴 Yuzhi zengding Qingwen jian (Imperially commissioned enlarged Manchu dictionary). One thing I find interesting about the Siti hebi wenjian is that the Mongolian and Tibetan translations seem to have been made directly from the Manchu, not via Chinese as we're used to seeing in multilingual materials these post-Qing days.

Here's what I think is some evidence for that fact. Some Manchu entries in the Siti hebi wenjian give the same Chinese translation, but different forms in Mongolian and Tibetan. An example of this is in the section on snakes and dragons (龙蛇类), seen here on a Chung Cheng university Manchu studies blog.

The second page has five Manchu expressions related to hibernation, or perhaps brumation since I think that's what snakes do (not so sure about dragons). The first three Manchu entries have the same Chinese translation: the first one is 'for snakes to begin hibernation' (蛇入蛰 shé rùzhé), while the next two are 'the same in Chinese' (汉语同上 Hànyǔ tóng shàng) and 'also the same in Chinese' (汉语亦同上 Hànyǔ yì tóng shàng). On the other hand, the Mongolian and Tibetan translate the Manchu one-to-one: the first two are

Mongolian: ᠮᠣᠭᠠᠢ ᠢᠴᠡᠭᠡᠯᠡᠮᠦᠢ moɣai icegelemüi могой ичээлмүй 'snakes hibernate'

Tibetan: ཁུང་ཉལ། khung nyal 'hibernate [in a hole]'

and

Mongolian: ᠢᠴᠡᠮᠦᠢ icemüi ичмүй 'hibernate'

Tibetan: ཚང་ཉལ། tshang nyal 'hibernate [in a nest?]'.

AntC said,

December 19, 2016 @ 10:12 am

Victor's opening paragraph brought me up short; and I read on through the article and all the comments without any clarification:

… words for "dog" in Japanese, "inu" and "ken", both written with the same kanji (sinogram; Chinese character): 犬.

So if that character means "dog", what possible difference could it make how it is pronounced? Does the debate amount to any more than whether to pronounce "either" as "ee-ther" or "ay-ther"?

OK, somebody might say "inu"; and that get written down as 犬; and somebody else might read it back as "ken". So what?

If it's about verse/rhyme/alliteration/scansion, the choice is obvious.

In English, "dog" and "hound" have somewhat differing meanings (or more likely, differing registers). But aside from compounds (Bloodhound/Bulldog), would it ever be actually wrong to say one rather than the other?

AntC said,

December 19, 2016 @ 10:18 am

BTW, if a writer deliberately wants their dog pronounced "inu" rather than "ken", is there a way to signal that?

Amy Stoller said,

December 19, 2016 @ 10:22 am

@Mr. Punch, @cameron, @maidhc, @J.W. Brewer, thank you for shedding some light on poodle dog. Boxer dog is new to me.

@Lazar, I’ve often wondered the same thing about tuna fish.

Jean-Michel said,

December 19, 2016 @ 1:16 pm

@AntC: BTW, if a writer deliberately wants their dog pronounced "inu" rather than "ken", is there a way to signal that?

Provide the pronunciation alongside the kanji using furigana. Or just don't bother with the kanji at all and write いぬ (hiragana)/イヌ (katakana) for inu, or けん (hiragana) for ken. (Ken could theoretically be spelled in katakana as ケン, but this seems to be uncommon–I assume because ken, unlike inu, is a bound morpheme and can't be used freely, and therefore isn't treated like unbound animal names that are often written in katakana.)

Victor Mair said,

December 19, 2016 @ 10:50 pm

@Jean-Michel

Perfect answer!

Jongseong Park said,

December 20, 2016 @ 2:26 pm

I was surprised to see the attempts to link Korean 개 gae 'dog' with 犬 (or even 狗).

Modern Korean 개 gae comes from Middle Korean 가히 gahi as jick says. A puppy is 강아지 gang'aji, from the combination with obsolete diminutive -ᅌᅡ지 -ng'aji 'baby' (compare 망아지 mang'aji 'foal' and 송아지 song'aji 'calf' for 말 mal 'horse' and 소 so 'cow'). Apparently G. J. Ramstedt did propose a link with Mongol gani 'a wild, masterless dog' (not the usual term for dogs in Mongol, which is nohoi~nohai or нохой in Khalkha), but I can't find info on any attempts to link Middle Korean 가히 gahi to 犬.

Jean-Michel, I must admit I don't remember hearing 견유 犬儒 gyeonyu for 'Cynic'. But the Sino-Korean element 견 犬 gyeon is used in enough derived words to be considered semi-productive, as in 애완견 愛玩犬 aewan'gyeon 'pet dog', 군용견 軍用犬 gunyonggyeon 'military dog', or 유기견 遺棄犬 yugigyeon 'abandoned dog'—the last being a neologism first recorded around 2004, but whose meaning is immediately apparent since people are familiar with 유기 遺棄 yugi 'abandonment' and the element 견 犬 gyeon.

The Sino-Korean element 구 狗 gu on the other hand appears in a handful of words like 백구 白狗 baekgu 'white dog' and set expressions like 토사구팽 兔死狗烹 tosagupaeng 'hare dies, dog boiled (i.e. killing the dog for food once the hare is caught, a metaphor for something that has outlived its usefulness)', and is not productive at all.

Please note that neither 견 犬 gyeon nor 구 狗 gu can stand on its own as a free noun in Korean, but only appears as an element in a word or set expression.

Eidolon said,

December 20, 2016 @ 8:34 pm

As far as I know, 犬 is considered to be the original word for 'dog' in Sinitic, and is possibly derived directly from proto-Sino-Tibetan. 狗 is considered an early borrowing – becoming popular already over 2,000 years ago – from either an ancient variety of Hmong-Mien or an ancient variety of Austronesian. Provided there have been no major changes to this understanding in recent years, it is curious that Japanese, Chinese, and English all have two popular words for 'dog.'

Japanese: inu, ken

Chinese: quan, gou

English: hound, dog

But I think I'm reaching here. After all, there are also more obscure English canine < Latin canis, Japanese kou < Chinese gou, and probably plenty more obscure terms for dogs in these languages.

Jongseong Park said,

December 21, 2016 @ 4:24 am

I don't know about referring to Sino-Japanese 犬 ken or Sino-Korean 견 犬 gyeon as 'words' for dog, since they cannot be free nouns but occur in compounds and fixed expressions only. I would just call them morphemes.

In Korean the prevailing practice for native dog breeds is to use 개 gae:

진돗개 珍島~ Jindotgae (진도개 Jindogae in North Korean spellling)

삽살개 sapsalgae, also called 삽사리 sapsari

풍산개 豐山~ Pungsan'gae

I have seen 진도견 珍島犬 Jindogyeon and 풍산견 豐山犬 Pungsan'gyeon in texts as well, but only the former appears as a variant of 진돗개 Jindotgae in the South Korean standard dictionary. Neither appears in the North Korean standard dictionary. 진도 珍島 Jindo and 풍산 豐山 Pungsan are Sino-Korean toponyms after which the respective breeds are named, so it would make sense that there are (probably old-fashioned) variants with -견 犬 gyeon. I was about to say that I didn't remember seeing 삽살견 sapsalgyeon, but this hangul spelling (without romanization) appears in the English-language Wikipedia article on Sapsali [sic]. 삽살 sapsal is not Sino-Korean.

Interestingly, the North and South Korean standard dictionaries recognize different sound insertion patterns for 진돗개/진도개 Jindotgae/Jindogae and 풍산개 Pungsan'gae (in this case manifesting as the fortition of the initial sound of 개 gae). In South Korea, 진돗개 Jindotgae is pronounced [진도깨] [ʣ̥ʲin.dok.kɛ] and 풍산개 Pungsan'gae is pronounced [풍산개] [pʰuŋ.z̥ʰan.ɡɛ], while in North Korea, 진도개 Jindogae is pronounced [진도개] [ʣ̥ʲin.do.ɡɛ] and 풍산개 Pungsan'gae is pronounced [풍산깨] [pʰuŋ.z̥ʰan.kɛ]. Note that because of different spelling rules in North Korea, they would still spell the former as 진도개 Jindogae even if they recognized the same pronunciation as in the South with the fortition. Both Koreas agree on there being no sound insertion (fortition) for 삽살개 Sapsalgae, pronounced [삽쌀개] [z̥ʰap.sal.ɡɛ].

Non-native breeds are usually just called by their original names as in 푸들 pudeul 'poodle', 테리어 terieo 'terrier', and 콜리 kolli 'collie'. Akitas appear on the standard dictionary in South Korea as 아키타개 Akitagae, but Korean Wikipedia currently goes for 아키타 견 Akita gyeon. Shibas don't appear in the standard dictionary but Korean Wikipedia currently has 시바견 Sibagyeon. I think this is because when Koreans see the kanji 犬, the automatic tendency is to read them as -견 gyeon rather than translate it to -개 gae.

Jongseong Park said,

December 21, 2016 @ 1:51 pm

Regarding the North-South pronunciation differences for 진돗개/진도개 Jindotgae/Jindogae and 풍산개 Pungsan'gae mentioned in the preceding comment, it may be relevant that 진도 珍島 Jindo is in South Korea and 풍산 豐山 Pungsan is in the North. Presumably, South Koreans are more familiar with the former breed and North Koreans with the latter. Sound insertion, which manifests as the fortition of the initial of -개 gae in this case, is to a considerable extent lexically determined, and one is less likely to pronounce an unfamiliar word with sound insertion when it is not clear from the spelling.

Chris Button said,

December 21, 2016 @ 11:07 pm

In his 1995 comparison of IE and OC, Pulleyblank actually tried connecting 犬 with 狗 and then with I.E. While his reconstructions are perhaps not entirely convincing, the comparison of 犬 with I.E. is nonetheless somewhat plausible. Using my reconstructions, 犬 as *kʰʷjanʔ or *kʰʷəɲʔ (earlier *kʰʷjənʔ) is not that far from IE *kʲwan (treating the I.E. e/o ablaut as ə/a).

Eidolon said,

December 22, 2016 @ 4:50 pm

"In his 1995 comparison of IE and OC, Pulleyblank actually tried connecting 犬 with 狗 and then with I.E. While his reconstructions are perhaps not entirely convincing, the comparison of 犬 with I.E. is nonetheless somewhat plausible. Using my reconstructions, 犬 as *kʰʷjanʔ or *kʰʷəɲʔ (earlier *kʰʷjənʔ) is not that far from IE *kʲwan (treating the I.E. e/o ablaut as ə/a)."

Since the current understanding is that dogs were domesticated *very* early, perhaps as early as 20,000 years ago or more, it might be possible for this be a very old wanderwort preserved from hunter gatherer days. How would you reconstruct it then?

Chris Button said,

December 22, 2016 @ 9:05 pm

@Eidolon

I'm assuming that's a somewhat tongue-in-cheek comment :)

The only thing I can speculate is that the ə/a ablaut would be a far more obvious surface phenomenon in the more primordial stages. By the time of OC, something like underlying *kʰʷjanʔ would actually have surfaced far more like *kʰʷenʔ approximating Baxter-Sagart's or Zhengzhang's reconstructions cited by Victor Mair above. The issue is that focusing on the surface phonology rather than the underlying phonology requires a forcing of the rhyme groups which results in numerous inconsistencies in the xiesheng series.