Comftrable

« previous post | next post »

Today's For Better or For Worse:

April's "comftrable" is not dictionary-sanctioned — but maybe it should be?

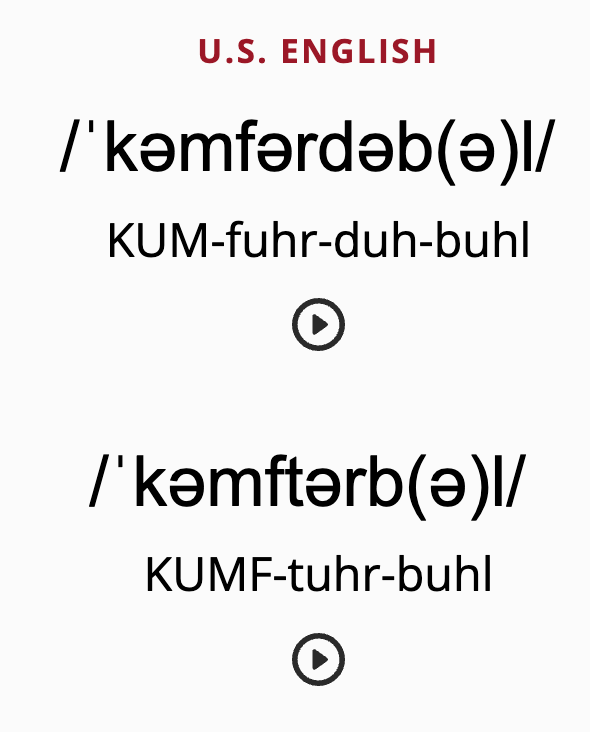

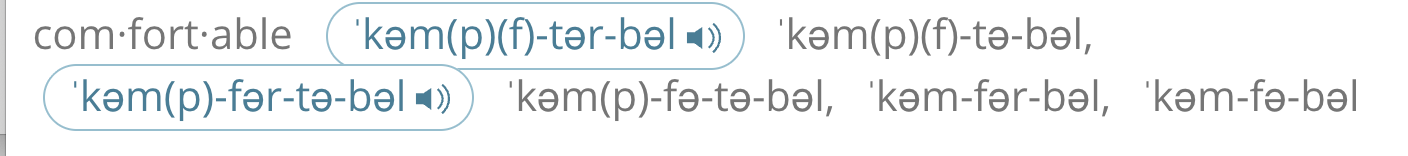

The OED offers two U.S. English pronunciations. The first one has all four syllables, while the second one combines the second and third syllable into one:

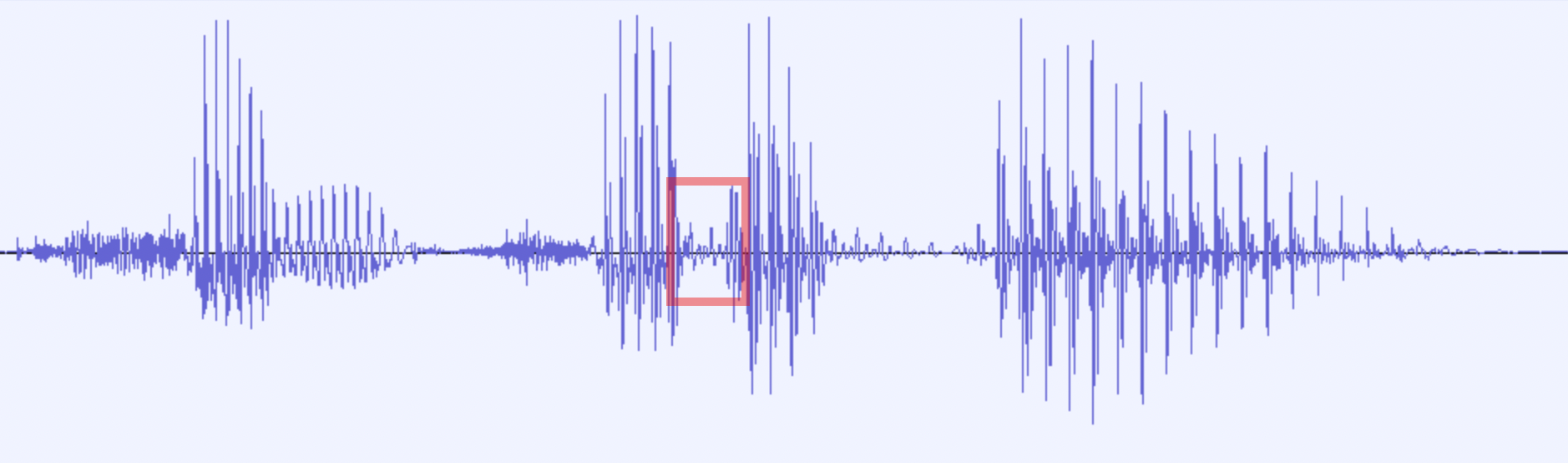

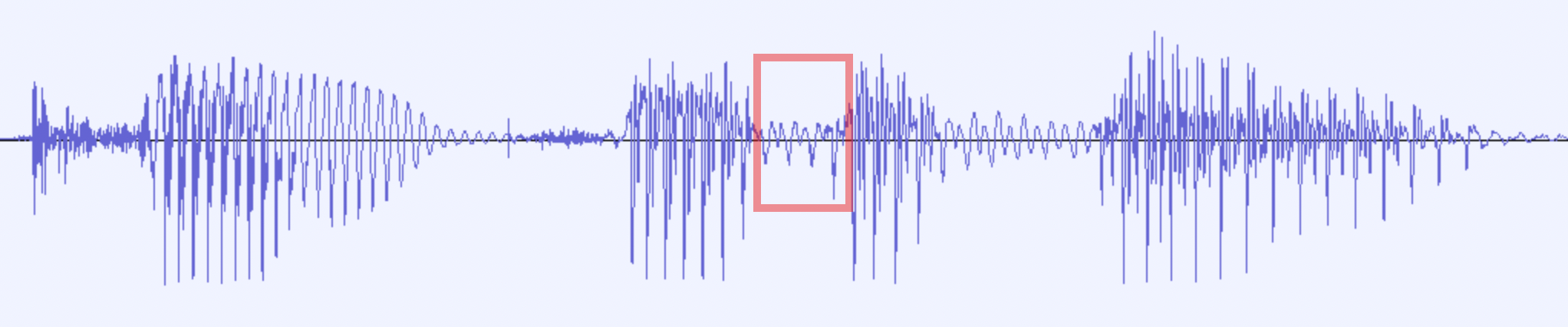

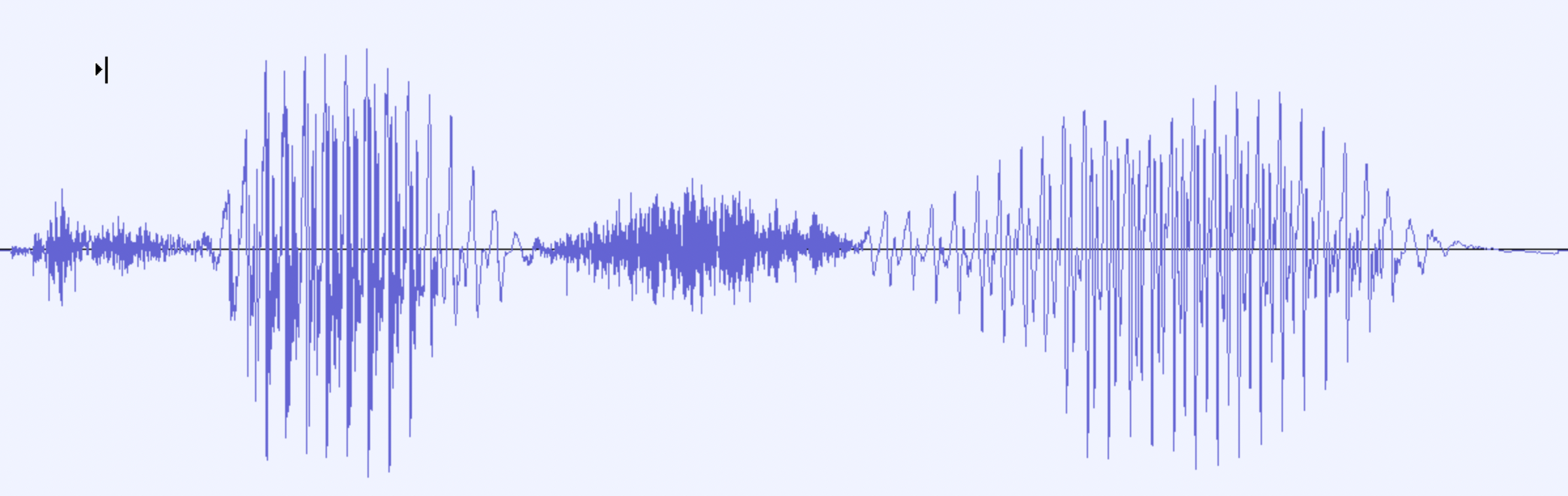

And in the first IPA string, the initial consonant of the third syllable, corresponding to the final 't' of comfort, is transcribed as a voiced [d], as we expect for a non-pre-stress intervocalic /t/. And that's pretty much consistent with the OED's audio — though at 21 milliseconds of closure, a fussy phonetician might transcribe it as a flap [ɾ]:

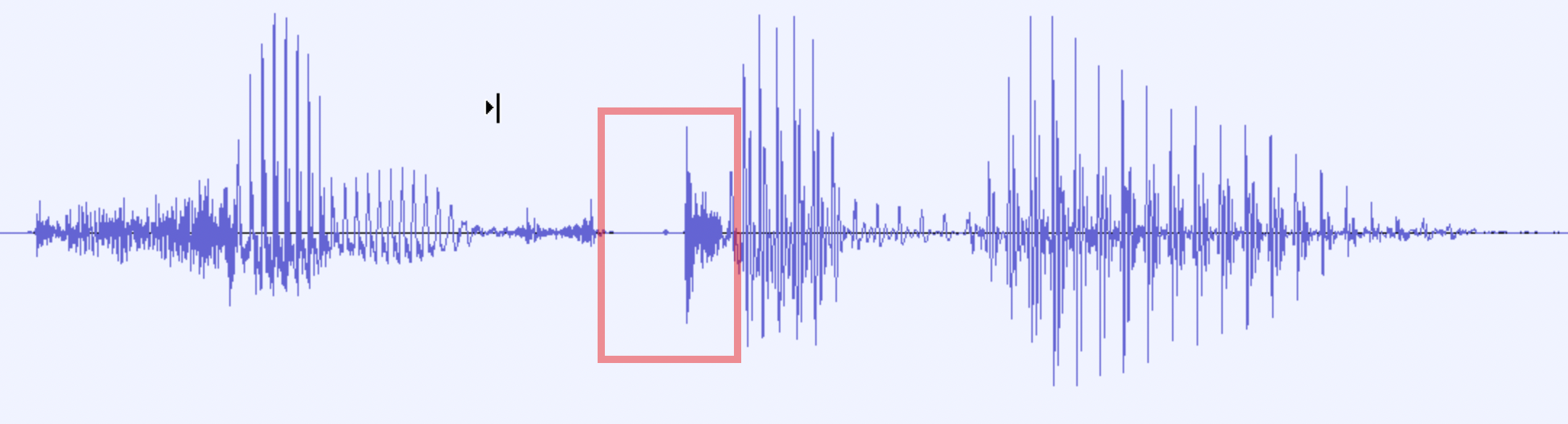

In the second pronunciation, the underlying 't' should be a voiceless aspirate, since it's no longer intervocalic — and that's indeed how it comes out in the associated audio:

Our fussy phonetician would transcribe the following syllable nucleus as a rhotic schwa [ɚ] , not the OED's [ər] sequence. Since the vocalic portion is only 57 milliseconds long, there's no time for such a sequence to be performed — and if we listen to the syllable, we can hear that it isn't:

But since I don't really believe in the IPA as a way of representing phonetic realization (though I might be fussy in other ways), I'll give them a pass.

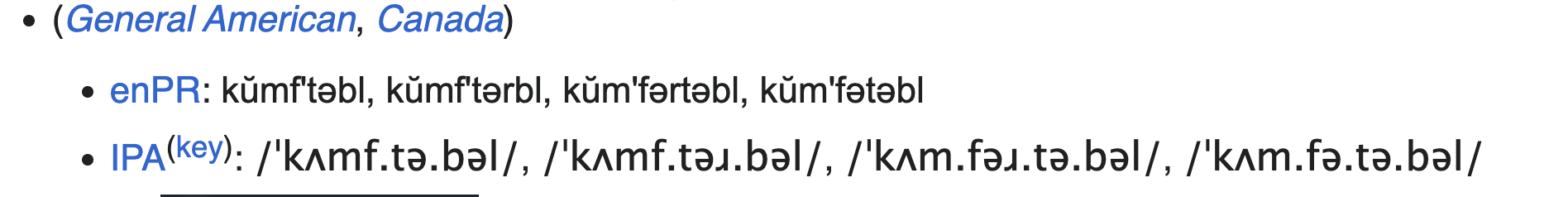

Merriam-Webster also offer two pronunciations, though in the opposite order, starting with the more reduced version:

And in the first pronunciation, we can agree with MW's [t]:

But in the second one, the [t] transcription is wrong — because the phonological /t/ is non-pre-stress and intervocalic, it again comes out as a voiced flap:

And again, the following syllabic nucleus is a rhotic schwa, not a schwa r sequence.

Wiktionary gives just one pronunciation — and it's the reduced one, with the /t/ rendered correctly:

The transcribed r-lessness of the second (phonetic) syllable in that performance seems correct, though it's so short that it's hard to tell:

But what about the [tr] cluster in April's "comftrable"?

As noted above, the vowel should be a rhotic schwa, not either [r ə] or [ə r]. Maybe April's pronunciation is slow enough for a transition to emerge? But more important, syllable-initial /tr/ is often produced as a post-alveolar affricate, and I suspect that's what April is doing.

I think that I sometimes say "comfortable" in that way as well. But listening to 100 examples randomly selected from the 4371 occurrences of "comfortable" in the previously-mentioned NPR podcasts dataset, I didn't find any clear examples of April's version. If any readers have made it this far, perhaps they'll give us their evaluation of their own range of pronunciations.

However, there were a couple of interesting cases in that sample that seemed to combine a fricative version of the /tr/ affrication, with an additional lenition of the /b/ to a syllable-initial [w], and reduction of the whole word to two phonetic syllables.

This is from a 2010 NPR podcast, in which Joseph Shapiro says:

but Katie says she feels most comfortable

when she's anonymous

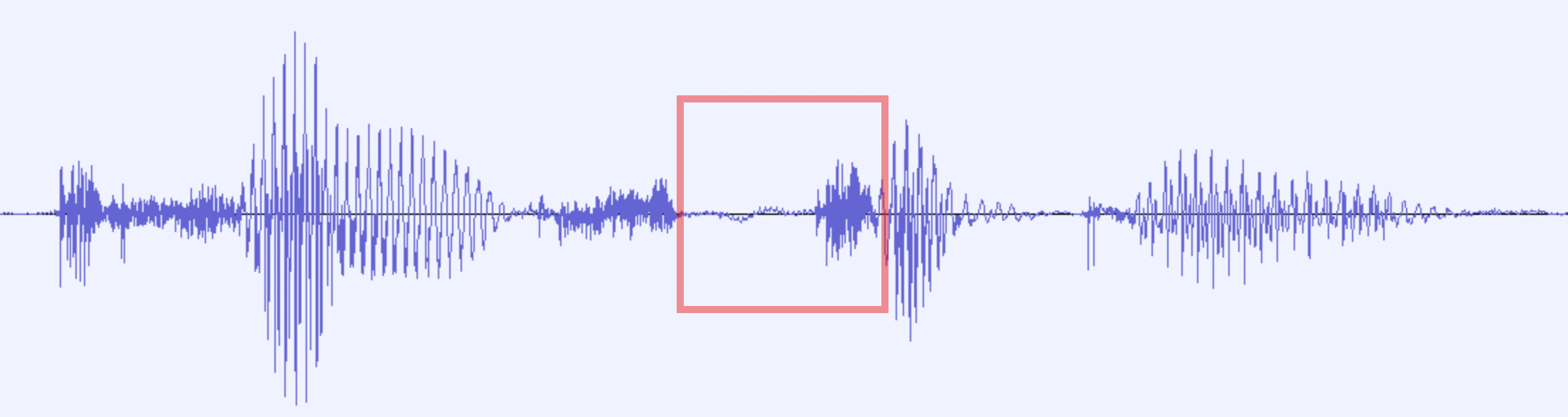

Zeroing in on "comfortable":

And now list to just the (monosyllabic!) "…table" part:

The corresponding IPA, if we're forced to render this performance of the word in those symbols, would be something like [ˡkʌm.ʃwl̩]. (That's a final syllabic [l], in case you can't see the "combining vertical line below"…). Of course, as I've observed more than once before, there's a more complex articulatory residue lurking unsymbolized in the acoustics.

It's striking that we don't even notice what he's done, unless we're looking at a visualization of the audio, or listening to the final (phonetic) syllable out of context.

And more generally, this is another good example of how actual pronunciation is massively undocumented, in English as well as all other languages. (Though there's more (allusive) documentation in comic strips than empirical coverage in the published literature, alas…)

Bob Ladd said,

September 21, 2025 @ 9:27 am

My normal pronunciation is definitely the "KUMF-tuhr-buhl" one. I seem to recall that I used to wonder about that when I learned to spell the word.

@MYL: When you write "Wiktionary give just one pronunciation", I assume this is a typo, not creeping BrEng plural verb agreement with collective subjects?

Mark Liberman said,

September 21, 2025 @ 9:37 am

@Bob Ladd "When you write "Wiktionary give just one pronunciation", I assume this is a typo, not creeping BrEng plural verb agreement with collective subjects?":

Yes — fixed now.

Philip Taylor said,

September 21, 2025 @ 9:37 am

More than a little confused by the image at http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/myl/OEDcomfortablePron.png — the IPA uses a schwa for the first vowel, whereas the first vowel in the Romanised re-spelling is a "U" which I (and, I am reasonably sure, most Britons) would pronounce /ʌ/ rather than /ə/. Is /kəm/ really how "kum" is pronounced in American English ?

Mark Liberman said,

September 21, 2025 @ 9:42 am

@Philip Taylor:

Yes, the OED should probably have used [ʌ] rather than [ə] for the first (stressed) syllable of "comfortable". But usage differs as to whether schwa can only be used a reduced/unstressed sounds — its vowel quality would otherwise work in that context.

Rodger C said,

September 21, 2025 @ 9:48 am

I believe this strip is Canadian. Is this relevant?

Philip Taylor said,

September 21, 2025 @ 9:59 am

Ah, the land of /ˈtrɒ·nə/ — I see what you mean, Roger …

Philip Taylor said,

September 21, 2025 @ 10:00 am

Oops, sorry, Rodger …

JMGN said,

September 21, 2025 @ 10:00 am

LPD gives /ˈkʌmpft/ for both AmE and BrE.

Philip Taylor said,

September 21, 2025 @ 10:14 am

Interestingly (to my mind), the LPD alsp shews an intrusive "p" in "Comfrey" (/ˈkʌmpf ri/) — I know that I definitely add a "p" to "Comfortable" (/ˈkʌmpf tə bəl/) but am certain that I don't add one to "Comfrey" (/ˈkʌm fri/).

Tom said,

September 21, 2025 @ 6:06 pm

We can't hear April speaking, so we don't know how she said it. The writing is obviously an attempt by the author to represent the OED's second pronunciation, but also I think it's an attempt to represent toddler-speak. Likely, the author should have written "comftrbl" to truly represent the toddler-speak effect he intended, but this would have caused reading problems for too many people (the fact that the "toddler-speak" is actually how adults say the word is another matter).

I am not a linguist, but as an English teacher in Japan who is responsible in part for pronunciation, I've found that discarding vowels often helps students with pronunciation. I tried different things over the years such as adapting speech therapy techniques, but when I starting showing students strings of consonants and asking them to just pronounce the consonants, their pronunciation improved a lot.

comfortable -> CMFtrbl

different -> DIfrnt

afterwards -> AFtrwrdz

As I said, I'm not a linguist, but the success of this approach has made me wonder if there aren't some "natural" vowel sounds for consonants. I know we have words like "camp", but "cm" seems to naturally come out like "comfortable" if people just pronounce a K and try to transition directly to an M.

JPL said,

September 21, 2025 @ 6:25 pm

How would you describe the difference in the pronunciation of what you call a "rhotic schwa", as opposed to what you might call a "syllabic r"? It seems like it would be difficult to hear a difference of that sort. (I can't make out a distinction between a completely open aspect and an aspect with the rhotic continuant.) For April's pronunciation, starting from the second American pronunciation, with the rhotic segment following, rather than preceding, the alveolar obstruent, there would seem to be three different possibilities, depending on whether she pronounced it with four, three of two syllables. (With the second syllable a rhotic schwa/syllabic r, followed by a schwa; with the second syllable a non-syllabic r, followed by a schwa; and Joseph Shapiro's two-syllable version.)

Whenever you say things like "there's a more complex articulatory residue lurking unsymbolized in the acoustics" I'm paying attention, because I think this is very important. More important than the categorical symbols and the differentiating diacritics is the descriptive terminology phoneticians have developed for describing articulatory movements independently of the "phones" a language takes as significant for distinguishing one form from another. In describing the actual articulatory process, you're not trying to "represent" the sounds in terms of their significance. In a field research context one is trying to move toward a phonemic interpretation, but one is not always trying to do that. You're trying to describe an independent empirical object, not provide an alternative expressive system.

DDeden said,

September 21, 2025 @ 6:33 pm

I've heard "comftabl" many times.

Andrew Usher said,

September 21, 2025 @ 6:46 pm

Philip Taylor, Mark Liberman –

No, /kəm/ is _not_ really how the first syllable of comfortable is pronounced by Americans. But worse, when dictionaries give 'American' pronunciations with stressed /ə/ alongside 'British' ones with /ʌ/, they imply a difference that doesn't exist. I don't know why the OED would adopt this policy for 'American' transcription, but a lot of dictionaries do, and they are not accurately recording usage. Respelling systems using only normal letters naturally used 'uh' for both sounds (in default of anything better), but that should not be carried over to IPA, which is able to distinguish.

Thanks to modern spectrum analysis, we know that since the beginning of recording the normal value for the 'cut' vowel in both America and in southern England has been near-low central, by the IPA chart /ɐ/, and both American and British speakers have often suggested that that symbol be used instead. My own impressions do not disagree with any of this.

This very instance has shown one harm caused by this misconception: as with other abuses of transcription, it can distract from the actual point being made.

Brett said,

September 21, 2025 @ 8:15 pm

@Andrew Usher: I'm sure there's variation, but my American pronunciation definitely has /ə/ rather than /ʌ/, in spite of the stress.

Andrew Usher said,

September 21, 2025 @ 9:32 pm

I can be fairly sure that you are wrong. Most people are not able to correctly analyse their own speech, and even phoneticians got things wrong before spectral analysis was available. You probably think that your first syllable of 'comfortable' is the same as your second syllable of 'incompatible' – but the latter as normally spoken has no vowel at all, and no formant frequencies.

I have known instinctively that the two vowels are different all my life, and I have repeatedly measured the formants to show that, in the same environment, my STRUT is massively lower than my schwa and actually nearer to my PALM/LOT, which is evident to my ears as well. I have evidence of several types that my speech is not unusual in this respect.

For completeness, note that the distinction is only possible before a consonant and (again, both in American and southern British speech) word-final schwa may be pronounced more like STRUT.

Joshua K. said,

September 22, 2025 @ 12:09 am

The cartoonist, Lynn Johnston, had the following comment about the use of "comftrable" here:

"Nobody corrected the word “comftrable” here. Usually, readers pounced on anything that had a colloquial spelling or was written in the vernacular. This time, I suspected that folks simply didn’t notice!"

https://www.fborfw.com/strip_fix/friday-september-19-2025/

Peter Cyrus said,

September 22, 2025 @ 1:50 am

"In the second pronunciation, the underlying 't' should be a voiceless aspirate".

Is the generalization that the second of two voiceless obstruents is usually aspirated? I had recognized that, for example, the /t/s in *act* and *apt* are aspirated, but I thought that was a side-effect of the unrelease of the preceding stop: the aspiration is a magnified release. Maybe I'm mistaken in the confusion between delayed VOT and the puff of aspiration.

But in [ˈkʰʌɱftʰɚbəɫ] , there's no preceding stop. What's aspirating the t?

Julian said,

September 22, 2025 @ 5:32 am

@Brett, Andrew Usher

I don't understand what a stressed schwa would be. It sounds like a contradiction in terms.

David Marjanović said,

September 22, 2025 @ 8:03 am

In rhotic American accents, [ʌ] is the stressed allophone of /ə/.

In Standard Southern British, [ɜ] is the stressed syllabic and [ə] the unstressed syllabic allophone of /ɹ/. /ʌ/ is a (marginally) separate phoneme in this kind of accent.

That's not natural, that's English. Or you could say it's natural in English.

Phonetic transcription of actual sounds goes in brackets [], not in slashes //.

What goes in slashes is phonemic transcription – phonological analysis of how the sound system of a particular accent works.

In most Englishes, stressed [ə] is indeed impossible; but that says nothing about stressed /ə/.

Tye S Power said,

September 22, 2025 @ 8:47 am

Some of my 5th grade students don't speak English as a first language and depend on their knowledge of phonics to get new words. Sometimes they learn a correct pronunciation they will hardly ever hear. So when they get to words like "comfortable" I might break them into roots and affixes say something like, "The word is *com-fort-ah-bull* but we usually say *cumf-ter-bl* because we are talking fast." This lets them see the parts of the word–which helps vocabulary development–and also understand common pronunciation.

Terry K. said,

September 22, 2025 @ 4:00 pm

I find it interesting (inneresting/intresting) that while comfterble (how I'd spell my pronunciation, if I had to) and comftrable seem very different to my mind, when I actually say them aloud quickly, the difference is minimal or non-existent.

I also find curious the reversal of the t and the r.

Chris Button said,

September 22, 2025 @ 7:16 pm

I'm sympathetic to your belief, but what do you propose?

It seems to me that where the IPA is failing you, is precisely where sound change is happening. But then again, how many "historical linguists" pay proper attention to phonetics in any case?

Andrew Usher said,

September 22, 2025 @ 8:15 pm

David Marjanovic says:

> In rhotic American accents, [ʌ] is the stressed allophone of /ə/.

That is demonstrably wrong. It would imply that [ʌ] can only be found in stressed syllables, yet – even if you go as far as possible in assigning secondary stress to every syllable with an unreduced vowel, itself dubious – the sound [ʌ] (i.e. [ɐ]) is found in word-final position where there is no stress at all. One can say, as I did, that the two phonemes are neutralised there, but that requires there be two phonemes to begin with.

>> "cm" seems to naturally come out like "comfortable" if people just pronounce a K and try to transition directly to an M.

> That's not natural, that's English. Or you could say it's natural in English.

Pronouncing 'comfortable' with syllabic M in the first syllable is _possible_, but not natural in any sort of English I know. When people say they seem to be 'transitioning directly from the K to the M' they are presumably inserting a vowel unconsciously.

> Phonetic transcription of actual sounds goes in brackets [], not in slashes //.

I know how they are supposed to be used, and when the difference matters it should be respected, but most people don't, including all those in this thread, and laymen for whom dictionary transcriptions are primarily intended certainly can't be expected to.

Having /ə/ in one dialect for the same sound as /ʌ/ in another is simply not appropriate there and will confuse people, as it confused Philip Taylor in his comment. Even if it were the unquestionably correct phonemicisation (and it's not), dictionaries are not written for theoretical linguists.

> In most Englishes, stressed [ə] is indeed impossible …

Rare, not impossible. I pronounce two items lexically with that vowel regardless of stress: 'just' (adverb/particle/whatever), which is normal fot Americans; and 'gonna', which is at least common. The former forms a minimal pair with the adjective 'just' (always STRUT) – sufficient to show the existence of two phonemes.

As for the spelling 'comfterble' or 'comftrable', yes, the first is how I'd write the common pronunciation. The 'comftrable' here probably didn't indicate anything different, but was just phonetically careless – as the OP stated, that spelling would be justified if we had the 'tr' sound followed by schwa (rather than syllabic R) but that's harder to say and uncommon. In the word 'temperature', where the preceding consonant is not alveolar, 'temperture' and 'temprature' are both heard about equally often.

David Marjanović said,

September 23, 2025 @ 5:25 am

Well, I didn't say anything about [ɐ] (which sounds noticeably different to me because of my native German)… I have noticed that unstressed /ə/ has some amount of allophony going on: the three pronunciations of data I've heard from Americans have different unstressed as well as stressed vowels – [de̞ɪ̯ɾɨ], [dæɾə], [dɑˑɾɐ] roughly.

Very good point – looks like you have a phonemic split there (following the historic merger).

That's what I'm saying.

Then they simply shouldn't use slashes at all, just brackets. (Some do.)

The idea seems to be that phonemic transcription means you don't need to get lost in phonemic detail that maps 1 : 1 between different accents anyway, and/or that you're only interested in how to pronounce a word in your own accent. But brackets don't specify a level of precision (and actual linguists routinely put very rough phonetic transcriptions in brackets).

Not necessarily. Our esteemed host has complained about "the alphabetic fallacy" before, pointing out all the coarticulation that occurs in real speech as opposed to one segment – one letter, one IPA glyph – coming after another; but such coarticulation isn't necessarily any kind of ephemeral transitional state. It can probably be stable for millennia.

Not enough, and it shows.

Bob Ladd said,

September 23, 2025 @ 7:15 am

The pronunciation of adverbial just with a “stressed schwa”, mentioned above by Andrew Usher, formed a key argument for the Trager-Smith phonological analysis of the English vowel system in the 1950s, except they used “barred I” ([ɨ]) to transcribe it. But it’s a stretch to treat this as a phonemic contrast, at least just on the basis of the word

just, because the real difference is that the pronunciation of the adverb is variable whereas the adjective is generally only [ʌ]. If you can find Gordon Lightfoot’s original version of “If you could read my mind” from the 1970s, listen to the variation in how he pronounces “and I just don’t get it” over multiple repetitions of the refrain.

The same variation shows up in Flemming and Johnson’s paper “Rosa’s roses”, except that here the schwa (or whatever it is) is unstressed: “roses” only ever has the [ɨ] pronunciation, but “Rosa’s” often has [ʌ] (or [ə], if you prefer).

JPL said,

September 23, 2025 @ 6:52 pm

@David:

"It seems to me that where the IPA is failing you, is precisely where sound change is happening."

"Not necessarily. Our esteemed host has complained about "the alphabetic fallacy" before, pointing out all the coarticulation that occurs in real speech as opposed to one segment – one letter, one IPA glyph – coming after another; but such coarticulation isn't necessarily any kind of ephemeral transitional state. It can probably be stable for millennia."

"But then again, how many "historical linguists" pay proper attention to phonetics in any case?"

"Not enough, and it shows."

Yes, I've also noted this, and I think Mark is onto something interesting. It's my impression that traditionally historical changes in morphs and word forms have been understood by reference to the process of articulating them, but that this has been done mostly by representing (identifying) the significant sounds using the IPA symbols, and then modelling the changes involved in allophonic differentiation of phonemic categories using devices like context-sensitive rules and other and modified IPA symbols, and then using this to understand processes like reinterpretation in the morphs and word forms. But doing it this way seems likely to miss a lot of the significant detail of what is actually happening in the articulation of forms, and so if you want to understand and explain processes of sound change, you don't need to be restricted to using the categorical symbols. It's possible to describe directly the concrete articulatory process in any detail you want, including all the coarticulations and tongue pathways you notice, independently of any assumptions of phonemic categories, using the terminology of articulatory phonetics. (Think of the terminology not as defining the symbols, but as descriptive of a physical process out there in the world.) You want to describe the mechanism that produces a particular kind of allophonic variation or reinterpretation, and you can determine a causal law for that that doesn't need to make use of the IPA categorical symbols. It seems to me that something like this is what Mark is trying to do, but I could be off the mark.

Chas Belov said,

September 24, 2025 @ 12:07 am

Phonetics are not my strong suit, but I think I pronounce it variously:

cəmf'təbl

cəmf'tərbl

or maybe with a half-r.

Andrew Usher said,

September 24, 2025 @ 7:36 am

Bob Ladd:

It's not just 'just', of course, that's merely one example to rebut claims that there couldn't be a minimal pair. It seems, by the way, that Brits do the 'just' thing also, though probably less consistently. Again, American and southern British English match perfectly in this respect, even if the phonetic values are a bit different.

And I certainly know the "Rosa's roses" paper, and that it makes a good case from the linguistic point of view; indeed, those are the same phonemes contrasting in an unstressed syllable, no matter how one chooses to write them. I didn't mention it because it's complicated to explain, especially with the notational strictness DM was insisting on – both words are variable, and may overlap, but the distinction is not only possible but actually made in most American speech.

Anyway the point of this here was that dictionary transcriptions that don't distinguish /ʌ/ and /ə/ are misleading and indefensible, and Philip Taylor was right to take it the way he did and to be sceptical. There may be no actual ambiguity in a primary-stressed syllable as here, but what about e.g. the first syllable of 'umbrella'? Is it reduced to schwa or not? – that's a meaningful question, and makes an audible difference, yet could not be expressed in the one-phoneme system, at least not in a way the normal reader would understand. With the distinction it's easy to clearly say that the standard pronunciation is unreduced /ʌ/.

David Marjanović said,

September 28, 2025 @ 9:02 am

Isn't Rosa's roses rather a lack of the rabbit/abbot merger?

…phonetic I meant, of course.

Or, again, you drop the slashes and the associated theoretical edifices and just say it's pronounced with [ʌ].

Andrew Usher said,

September 29, 2025 @ 7:57 am