English is innocent

« previous post | next post »

Yesterday's guest post by Andreas Stolcke, "English influence on German spelling", covered Duden's grudging admission that 's is allowed in certain restricted contexts, and noted the widespread negative reaction attributing this "Deppenapostrophe" (= "idiot's apostrophe") to the malign influence of English.

But Heike Wiese, via Joan Maling, sent a link to Anatol Stefanowitsch, "Apostrophenschutz", Sprachlog 4/26/2007, which offers a very different take.

Wann kamen die „Deppenapostrophe“ hinzu? Glaubt man den Apostrophenjägern, so muss dies in jüngerer Zeit geschehen sein, da ein intensiver Einfluss des Englischen sich erst seit dem Ende des zweiten Weltkriegs beobachten lässt, und die vemeintlichen Hauptschuldigen, die Elektronikmärkte, gibt es sogar erst seit dem Ende der siebziger Jahre. Eine schöne Erklärung, mit der man die Apostrophitis als eins von vielen Symptomen des „denglischen Patienten“ abhaken könnte.

Leider ist diese Erklärung falsch.

Der Genitiv-Apostroph findet sich bereits seit Mitte des 17. Jahrhunderts, erst bei Eigennamen und bald auch bei Ortsnamen und anderen Wörtern. Der Plural-Apostroph findet sich seit dem Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts. Zunächst störte sich auch weiter niemand an diesen Verwendungen.

When did the "idiot apostrophes" come into being? If you believe the apostrophe hunters, this must have happened more recently, since the intensive influence of English has only been evident since the end of the Second World War, and the supposed main culprits, the electronics markets, have only existed since the end of the 1970s. A nice explanation that could be used to write off apostrophitis as one of the many symptoms of the "Denglish patient."

Unfortunately, this explanation is wrong.

The genitive apostrophe has been around since the middle of the 17th century, first in proper names and then in place names and other words. The plural apostrophe has been around since the end of the 18th century. At first, no one was bothered by this use.

Stefanowitsch's examples unfortunately don't go back to the 17th century, but they do include these, from someone who was neither an idiot nor a sufferer from Denglish disease:

In Friedrich Nietzsches Briefen und Notizen beispielsweise finden sich hunderte von Genitiv-Apostrophen:

Vielleicht sieht sich unser Gebahren doch einmal wie Fortschritt an; wenn aber nicht, so mag Friedrich’s des Grossen Wort auch zu uns gesagt sein und zwar zum Troste … (Menschliches, Allzumenschliches I/Nachgelassene Fragmente).

Ich gehe, seit einigen Monaten schon, jeden Abend von 1/2 10–11 in raschem Schritt durch Theile Venedig’s (Brief von Heinrich Köselitz an Nietzsche, 1882)

Aufs Kind die Hände prüfend legen Und schauen ob es Vater’s Art — Wer weiss? (Menschliches, Allzumenschliches I/Nachgelassene Fragmente)

In Friedrich Nietzsche’s letters and notes, for example, there are hundreds of genitive apostrophes:

Perhaps our behavior will one day be seen as progress; but if not, then Frederick the Great’s words may also be spoken to us, and indeed for consolation … (Human, All Too Human I/Posthumous Fragments).

For several months now, every evening from 10:30 to 11:00 I have been walking briskly through parts of Venice (Letter from Heinrich Köselitz to Nietzsche, 1882)

Lay your hands on the child and examine it and see if it is like the father — who knows? (Human, All Too Human I/Posthumous Fragments)

Stefanowitsch's account suggests that German apostrophe-phobia, like most cases of prescriptivist peeving, originated as the decision of a self-appointed authority, in this case Konrad Duden:

Erst ab Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts trafen diese Verwendungen auf Widerstand. Vor allem die Entscheidung Konrad Dudens, sie explitzit als regelwidrig zu behandeln, trugen zu ihrem Niedergang bei. Nicht jeder ließ sich allerdings von diesen Verboten beeindrucken. So soll Thomas Mann den Apostroph nach Lust und Laune weiterverwendet haben.

It was not until the middle of the 19th century that these uses met with resistance. Above all, Konrad Duden's decision to explicitly treat them as illegal contributed to their decline. However, not everyone was impressed by these bans. Thomas Mann is said to have continued to use the apostrophe as he pleased.

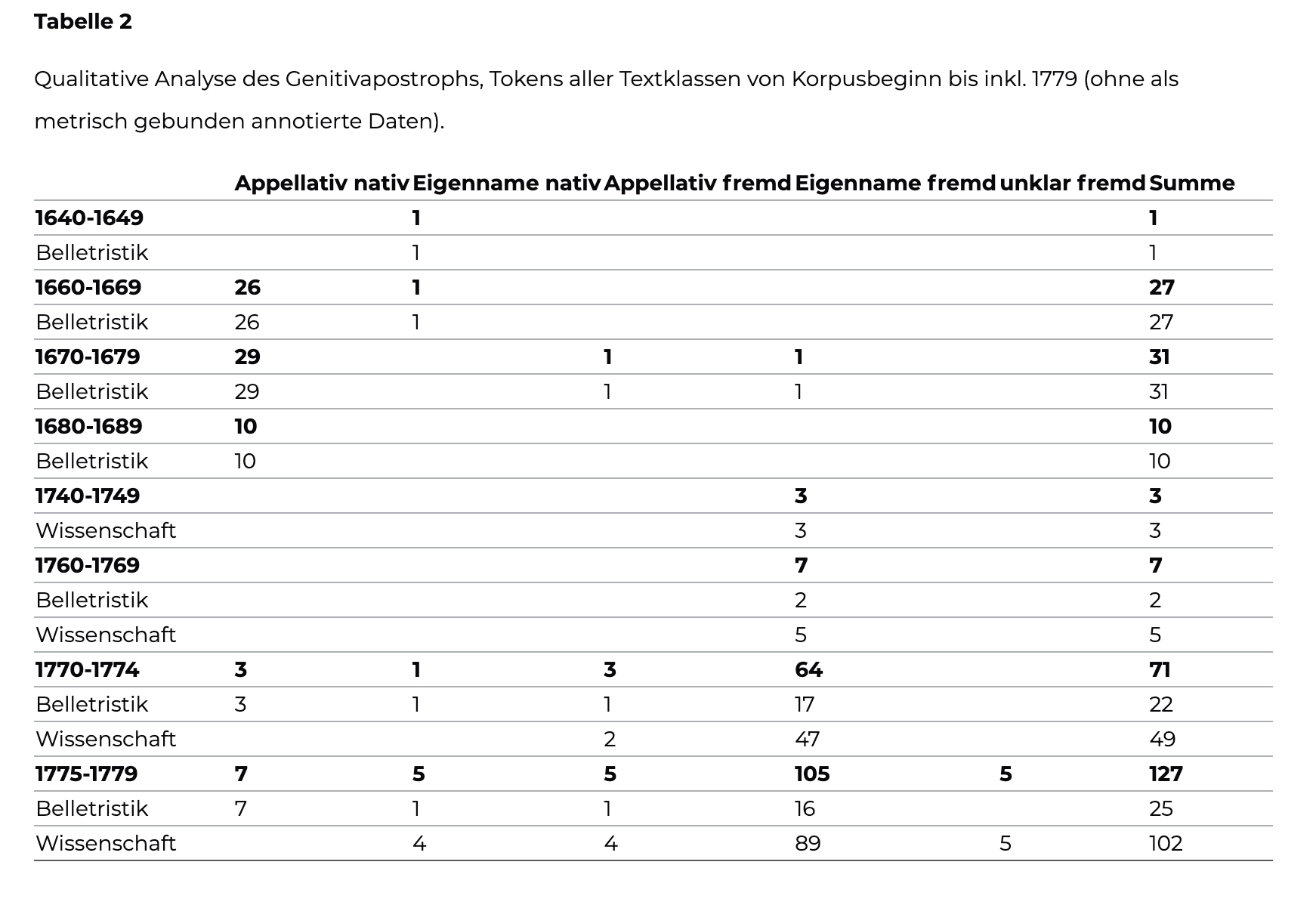

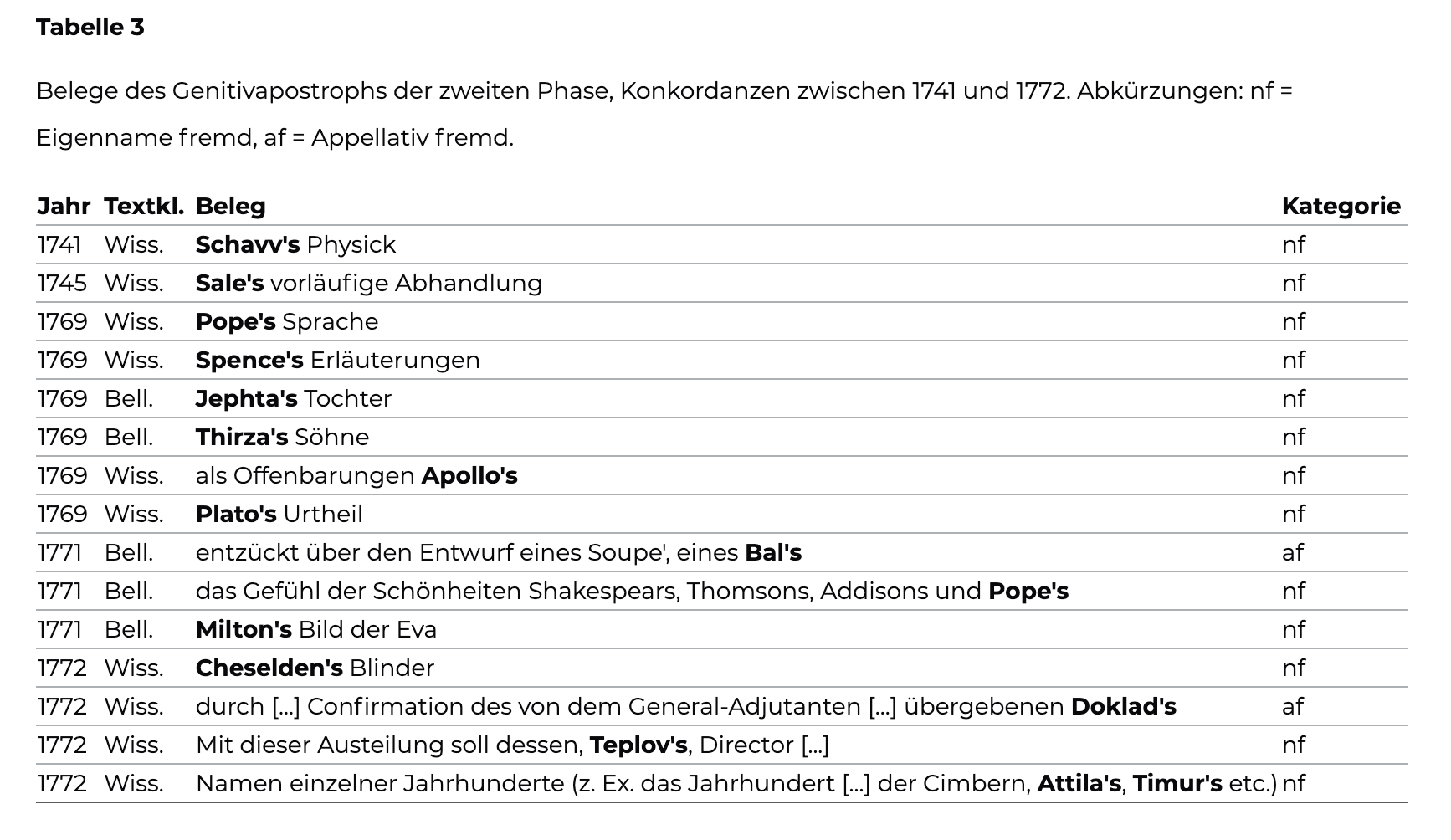

For a more recent and extensive survey of the topic, we should turn to a source that I've barely had time to skim: Luise Kempf, "Die Evolution des Apostrophgebrauchs: Eine korpuslinguistische Untersuchung." Jahrbuch für germanistische Sprachgeschichte (2019). My impression so far is that foreign names do play a pre-Duden role, as indicated in these tables:

But the recent influence of English is definitely not the whole story.

Yves Rehbein said,

October 10, 2024 @ 11:26 am

The 1769 wissenschaftlich Textklassen-Beleg "Plato's Urtheil" is suggestive. The only form in current use is Platon (as in platonic). The current English form that rhymes with play-doe (solids!) is not justified by Greek. Unless the 1769 text was from English, it is more likely to be blamed on the Frã, cf. \pla.tɔ̃\, beginning with Latin Plato. Even then, platonisch (solids!) remains quite close to L. gen. platonis, though we should be comparing Platonicum (Corpora!).

Unfortunately, this argument is entirely of platoniġ (as my Hessian lecturer with /ʃ ç/ merger would say, probably).

N. N. said,

October 10, 2024 @ 5:43 pm

Connoisseurs of German philosophy are also familiar with Julius Frauenstädt's edition of "Arthur Schopenhauer's [sic] sämmtliche [sic] Werke" from the 1870s, reprinted well into the 20th century.

Andrew McCarthy said,

October 10, 2024 @ 6:49 pm

I recall reading that Richard Wagner’s spelling of the title of the early draft of what later became Goetterdaemmerung (umlauts substituted as I’m typing on an iPad) was Siegfried’s Tod – “complete with ‘English’ apostrophe,” as one commentator put it.