Of chariots, chess, and Chinese borrowings

« previous post | next post »

Having gotten a good earful of Latin last month, Chau Wu was prompted to write this note in response to our previous post on "From Chariot to Carriage" (5/5/24):

“chē 車 ("car; cart; vehicle") / yín 銀 ("silver")”

In my view, these two words are among those most representative of cultural and linguistic transfers from West to East. This comment will focus on 車 chē only. 車 is pronounced in Taiwanese [tʃja] (POJ chhia), quite similar to the first syllable char- of English chariot. I believe, like E. chariot and car which are derived from Latin carrus (see Etymonline on car and chariot), Tw chhia is ultimately also a derivative of L. carrus.

More interestingly, 車 has a second pronunciation, which is the traditional one. In reading Classical Chinese / Literary Sinitic, 車 is pronounced in MSM jū, which I learned in my high-school Chinese class. In the Taiwanese literary reading, 車 is read ku. For example, there is a famous phrase 出無車 from a classic story about Feng Xuan 馮諼, a retainer of Lord Mengchang of Qi during the Warring States period, as recorded in 史記 Shĭjì ‘Records of the Grand Historian’ (孟嘗君列傳 ‘Biography of Lord Mengchang of Qi’) and 戰國策 Zhànguócè ‘Stratagems of the Warring States’; this phrase should be pronounced in Tw chhut bû ku / MSM chū wú jū.

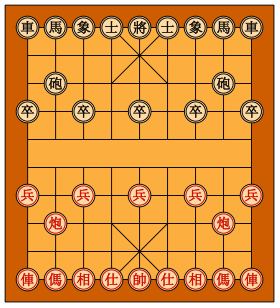

Furthermore, in Chinese chess xiàngqí 象棋, which, like Western chess, comes from India, there is a piece named 車 ‘chariot’ whose movements are identical to those of the rook/castle in Western chess. This piece is called in Tw ku and MSM jū, preserving its Classical Chinese pronunciation.

A xiangqi board in the starting position. (The black pieces would normally be facing the player, but here they are rotated to be readable.) From Wikipedia.

In the Warring States period, a game by the name of 象棋 xiangqi was mentioned in the first-century-BC text Shuo Yuan 說苑, which states that it is one of Lord Mengchang of Qi’s interests. This leads me to believe that the literary pronunciation of 車 (Tw ku), especially of the chess piece, is the living fossil of its Old Sinitic pronunciation. What is the source of this old pronunciation?

My study of West-to-East lexical loans suggests that the literary reading of 車 (Tw ku) ‘chariot, car’ is a loan from Latin currus ‘a chariot, car’. This hypothesis receives strong support from a totally unexpected source, the native Japanese vocabulary (大和言葉 Yamato kotoba). Let me briefly explain as follows.

L. currus is an italic cognate of Gallo-Latin carrus. It is a fourth declension word with the accusative form currum. For example, “currum agere” means ‘to drive a chariot’. It is common knowledge that Romance languages inherit Latin nouns from the accusative forms. For example, L. carrum (acc. of carrus) > Vulgar Latin *carra > Old French carre > Middle English carre > Eng. car. But unlike L. carrus which has a long list of descendants in modern European languages, currus has left no heirs in Europe.

However, when the Japanese word kuruma くるま ‘vehicle, car; automobile’ is compared with L. currum (acc. of currus) ‘a chariot, car’, and with the knowledge that Japanese words have open coda (except -n), it is immediately clear that currum may have been borrowed by Proto-Japanese, suffixed with a vowel -a for open coda, and thereby nativized into their Yamato kotoba lexicon (Cf. Sino-Japanese sha for 車).

With Japanese kuruma as our guide, it follows that L. currum may have come to Asia and may have been borrowed into Proto-Japanese and Old Sinitic. The Taiwanese literary reading of 車 (ku) represents the first syllable of currum adopted into Old Sinitic.

[VHM: When I first made this post, I did not realize that Chau Wu's note had a second page. He has requested that I add it now. Everything after the illustration of the xiangqi board down to this note was missing from the first post.]

Chris Button had written this comment to the "From Chariot to Carriage" post:

It's nice when archeologically focused articles like this back up the linguistic evidence that the word represented by 車 is a loanword.

I've recently been looking at 銀, which for about 150 years has been treated as a loan into Tocharian. The problem is that the Chinese evidence doesn't support that. An article by Witczak independently proposes an internal evolution of the word in Tocharian. If correct, the direction was almost certainly Tocharian into Chinese.

[CB note: Minor typo: I meant 50 years rather than 150 years. Although it could have been proposed before then. It seems Adams' Dictionary has a reference to Rahder from 1963, but I haven't seen that.]

Chariots or silver, the other issue is a reliable Old Chinese reconstruction, which cam then be reinforced by the proposed loanword origin rather than manipulated to fit it. But that's another matter

This is why Chau brought up chē 車 ("car; cart; vehicle") and yín 銀 ("silver") together here. I expect that some combination of Chau, Chris, Doug (see forthcoming article below), and others will further enlighten us on the antecedents of yín 銀 ("silver") in Sinitic in due course.

Selected readings

- "From Chariot to Carriage" (5/5/24) — with a lengthy bibliography of relevant posts

- "Bronze, iron, gold, silver" (1/29/21) — with a long bibliography of posts relating to metallurgy

- "Latin oration at Harvard" (5/9/24)

- Douglas Q. Adams, "Resurrecting an Etymology: Greek (w)ánax ‘king’ and Tocharian A nātäk ‘lord,’ and possible wider connections", forthcoming in Sino-Platonic Papers.

Jerry Packard said,

June 7, 2024 @ 12:13 pm

I seem to recall that the the pronunciation of 車 was jū when used as part of the (ostensibly monomorphemic) word 車馬 juma meaning something like ‘military materiel.’ I’m checking with a knowledgeable friend and will get back on this if appropriate.

Jonathan Smith said,

June 7, 2024 @ 2:08 pm

More normally [tɕʰi̯a] or sth for Taiwanese 'car', [tɕʰ-] etc. being synchronic allophones of [tsʰ-] etc. The everyday word is as always more interesting than literary items… one thing is that (like cognates in other Chinese) this word can refer more generally to machines featuring wheels and also (like cognates in some other southern Chinese) be a verb 'operate a wheeled mechanism' (if indeed these all reflect a single historical etymon.) Maybe even homophonous 'push over, turn [e.g. a flip]' is a cognate?

Of course the above are presumably related to che1 車 of Mandarin, etc.; the Chinese item(s) in turn could well be borrowing/s from Indo-European as suggested by most authors (?)…

Jonathan Smith said,

June 7, 2024 @ 2:08 pm

should be */tsʰ-/ etc.

Jerry Packard said,

June 7, 2024 @ 2:39 pm

My S. Min teacher only ever used the pronunciation [tsʰi̯a] (7th tone) for 車.

KIRINPUTRA said,

June 8, 2024 @ 2:49 am

Tone aside, [tsʰi̯a] is the conservative form post-[tsʰia], and not uncommon outside the bubble tea bubble.

In Taioanese, at least, degree of palatalization correlates with youth & Mandarin-preference. CHH- before -I is lightly palatalized (or not) for the Mandarin-free & Mandarin-challenged.

Jerry Packard said,

June 8, 2024 @ 6:31 am

My knowledgeable friend (Shengli Feng) informs me that 車 was pronounced jū when used in the word 車馬, and that 車馬 simply meant ‘chariot’, with the 馬 appended to fulfill the requirement of bisyllabicity, and that ju was simply the more conservative, archaic pronunciation.

Jerry Packard said,

June 8, 2024 @ 8:24 am

“This leads me to believe that the literary pronunciation of 車 (Tw ku), especially of the chess piece, is the living fossil of its Old Sinitic pronunciation. What is the source of this old pronunciation?”

I don’t have my Laurent Sagart books with me here, but it wouldn’t surprise me to find that Sagart views it as a grammatical prefix.

For what it’s worth, the Baxter-Sagart reconstructions for che and ju respectively (with apologies for lack of font transfer) are

*t.qh(r)A che chariot

*C.q(r)a ju chariot

with the h standing for aspiration.

Chris Button said,

June 8, 2024 @ 10:07 am

I reconstruct 車 as (pre-)Old Chinese kə̯ᵏlaɣ giving Old Chinese ᵏɬaɣ with the aspiration following Pulleyblank's suggestion that it results from the reduplicated k- in the onset (ɬ being the realization of ʰl). The connection with Tocharian käuk(ä)le “cart, wagon” is apparent.

In my system, ᵏl- and ᵏr- were allophones that merged in one syllable type as if from kr- but diverged in another syllable type (the one for 車). So I would suggest that the variant "jū" pronunciation for 車 goes back to a variant kə̯ᵏraɣ that dropped the presyllable to leave ᵏraɣ from which it can then be regularly derived.

I would reconstruct 銀 internally as Old Chinese ᵑgrən to give Early Middle Chinese ŋin. That chimes well with Tocharian nkiñc ~ ñkante. The OC medial -r- is needed to account for EMC ŋin rather than ŋɨn, but it may well be spurious if the EMC vocalism is reflective of the Tocharian loan instead of an OC pedigree.

I favor the internal origin based on onomatopoeic words for revolving/rolling like kurukuru and korokoro. The Indo-European source of Tocharian käuk(ä)le is perhaps onomatopoeic too, so a connection has been proposed there (I'm looking at Yamanaka Jota's "Kokugo gogen jiten"), but I doubt there is any etymological connection–just somewhat similar onomatopoeia. No idea regarding final -ma though.

Jonathan Smith said,

June 8, 2024 @ 10:49 am

very interesting re /ts-/ etc. in these languages…

e.g. in his dictionary of 1873, Douglas writes "ch-" before (high front) "i" and "e" but "ts-" elsewhere, consistently describing the former as "unaspirated" and "as in [English] church[/i]" in contrast to "ts-" — this division oif labor was "phonologized" or sth. to simply "ch" in POJ proper. However Douglas uses only "chh-" for the aspirated value(s), while allowing that this is often like "tsh-" (unused in his spelling) in the "ts-" type contexts…

Rodger C said,

June 8, 2024 @ 12:11 pm

I'll be the one to point out that in Classical Latin the ending -um was pronounced as nasalized *[u:], which for some reason my Word program doesn't want to represent at the moment. It was scanned as a vocalic ending.

Chris Button said,

June 8, 2024 @ 6:53 pm

Actually a simpler explanation for could be kə̯ᵏlaɣ giving ᵏɬaɣ for the first option but fusing to kaɣ for the second and then developing regularly without palatalization of the onset due to the pharyngealization associated with the velar coda in the evolution to Middle Chinese (as Pulleyblank suggests).

Chris Button said,

June 8, 2024 @ 7:10 pm

So ᵏɬ- invariably gives ʨʰ in this syllable type

While k- only gives ʨ- in this syllable type under the right palatalizing conditions.

And that perhaps explains the EMC i ~ ɨ variation too. So …

chē (OC ᵏɬaɣ, EMC ʨʰiaa̯, LMC tʂʰiaa̯)

jū (OC kaɣ, EMC kɨə̯, LMC kiə̯)

Both ultimately from kə̯ᵏlaɣ from Tocharian.

KIRINPUTRA said,

June 9, 2024 @ 12:03 am

@ Jonathan Smith

Douglas mentions the other convention in his appendix. Split ran through Teochew as well. Vague impression: It was Brits vs Yanks (but all Presbyterians) at one point.

Re-reading Douglas: In Hokkien, at least, maybe [tsʰi̯a] & [tsʰia] are NOT conservative. And there is sometimes palatalization (?) where CHH-, J-, & S- meet non-high-front vowels in Hokkien (at least S’porean) & old folks’ Taioanese (in the Seaward dialect, at least).

@ self (check)

[ia] is def. still part of the mix. Just heard SIÁ pronounced [siːa] last night. Expressive tone of voice but no specific emphasis.

KIRINPUTRA said,

June 9, 2024 @ 12:13 am

FWIW, the Sino-Hoklo or Sino-“Southern Min” reading of 車 seems to reconstruct to /*kɨ/ (POJ "KṲ") or similar.

Jonathan Smith said,

June 9, 2024 @ 2:32 pm

@KIRINPUTRA

Yeah re: these phonemes, maybe something is not done quite right in current reconstructions at say the SMin level. The normal assumption seems to be that early /ts-/ simply developed a palatal allophone ≈[tɕ-] before /i/, /e/ in Amoy, etc. (cf. my first post / Douglas's "ch-"/"ts-")… but Douglas's preference for "chh-" NOT "ts-" across the board, and your observation of "palatalization (?) where CHH-, J-, & S- meet non-high-front vowels in Hokkien", might suggest that the proto-value was post-alveolar or maybe even that there was an earlier contrast between /ts-/ and ≈/tʃ/ which subsequently merged in different ways? (FWIW I have also suspected/written somewhere that what is normally treated as a singular PMin /d-/ as in both 'tea' and 'bean' might have been two values… no idea if this is right or related to the situation with the affricates.)

Jonathan Smith said,

June 9, 2024 @ 2:33 pm

*NOT "tsh-"

Chau said,

June 10, 2024 @ 11:20 am

@ Roger C : “in Classical Latin the ending -um was pronounced as nasalized *[u:]”

Thank you for bringing up this good point. This is well stated in textbooks of Latin as part of the general characteristic feature of Classical Latin:

“A terminal m nasalizes the preceding vowel. The consonant itself is scarcely pronounced.”

However, I doubt that this feature spread widely throughout the vast expanse of Roman Empire. Most likely, it was characteristic of the upper-class accent in the power center. If my hypothesis that Japanese kuruma (くるま) ‘vehicle, car; automobile’ and Tw ku (車) ‘chariot, car’ are loans from Latin currum (acc. of currus) ‘chariot’ is tenable, then we may surmise that the speakers who donated the word may have been merchants, mercenaries, migrants, or raiding hordes venturing into the exotic East Asia. They may have sprung from the border regions of the Empire and their accents might not be similar to that of the privileged social class in Rome.

To clarify this point, I think it is pertinent to draw on the rhotic and non-rhotic variation of English as an example. D. Costa and R. Serra in their paper on rhoticity in English (Frontiers in Sociology, 2022; 7: 902213) state that, “All English accents were rhotic up until the early Modern English period and non-rhoticity variety was a relatively late development. It is said to have started in 18th century as a prestige motive in socio cultural contexts in British culture.”

Therefore, I think, it is possible that the “terminal m nasalization rule” (mentioned above) may also have been a speech innovation with a prestige motive in socio-cultural contexts in Roman culture.

Chris Button said,

June 10, 2024 @ 6:24 pm

I think Prof. Mair's suggestion (discussed on LLog elsewhere) that 犬 and 狗 represent loans of the same original PIE etymon at different time depths makes good sense. However, I don't think the same case can be made for the two pronunciations of 車. When reconstructed back to Old Chinese, the pronunciations are clearly related.

On a separate note, the pronunciation of -m as nasalization of the preceding vowel is maintained in Portuguese.

Chris Button said,

June 11, 2024 @ 6:40 am

Straying off topic, does anyone know anything about the origin of the -m spellings in Portuguese? Latin orthography was presumably the influence, but it happened in words that never had final -m in Latin.

Jonathan Smith said,

June 11, 2024 @ 1:25 pm

IDK re: Portuguese but I have seen a couple of idiosyncratic~non-etymological spellings of Amoy/Taiwanese -iũ words (maybe others?) as "ium" in older Romanized materials… what follows is presumably relevant to this choice but I didn't make notes unfortunately…

Vampyricon said,

June 19, 2024 @ 5:42 pm

What actually is the proposal here? That Romans came to East Asia on chariots and gave the word for chariot to both Sinitic and Japonic?

Again, as per Rodger, Latin ⟨currum⟩ was pronounced [ˈkʊrʊⁿː] (with superscript n standing in for nasalization). Perhaps during the proto-Italic stage it had an actual [m] sound, but then the other consonants pose a problem, as it was (I think) *korzom, which means there's an unexplained *z.

Further problems arise when one realizes that the consensus among linguists is that the velar pronunciation of the word 車 is the older one, which means it can be traced back to the oracle bone script of the Shang, in the 1200s BC. For comparison, Old Latin has been attested since only the 800s BC, and the change of z > r was only attested starting around 350 BC.

Just to make it *abundantly* clear, this borrowing would have to require the proto-Italics, or the Romans *time-travel* at least 200 years into the past, or closer to 900 if one wants to be rid of the *z, travel all the way to East Asia without any record of their journeys being uncovered, and still have trouble reconciling the vowels with the Sinitic form, as later Sinitic *-u is known to come from earlier *-a. The word for Japonic is less problematic, if only because of its late attestation, but there is precious little time between the rhotacism of *-z- and the loss of *-m that the Romans could contact the pre-proto-Japonics and lend them their word for chariot, which had already existed in East Asia for just shy of two millennia.

銀 has smaller but substantial issues, as cognates seem to be easily found in other Trans-Himalayan languages, like Old Tibetan and Old Burmese. There is a robust correspondence between Old Chinese *-r and Old Tibetan *-l, which involve lexical items of a basic nature, like "liver". Baxter and Sagart's *ŋrə[n] would be correct if it were actually *ŋrər (compare Old Tibetan dŋul and Old Burmese ŋuy), and is suggested by Nathan Hill in his 2019 The Historical Phonology of Tibetan, Burmese, and Chinese. These three forms seem to go back to a common ancestor roughly of a form *rŋəɾ (where I use ⟨ɾ⟩ to label Hill's ⟨rl⟩), with the following sound changes giving the three forms:

– Sinitic: *rŋəɾ > *rŋər (metathesis + *ɾ > *r)

– Tibetic: *rŋəɾ > dŋəl (fortition + *ɾ > *l)

– Burmic: *rŋəɾ > ? > *rŋuɾ > *rŋul > rŋuy

The vowel correspondence seems off in Burmic, but its developmental similarity to *-əw- > *-u- should not be ignored.

In both cases, I don't see a good argument for these developments either tout court or that can't be better explained by pre-existing theories.

Chris Button said,

June 20, 2024 @ 7:11 am

@ Vampyricon

The Burmese form is an isolate in Lolo-Burmese.

Vampyricon said,

June 20, 2024 @ 10:51 am

@Chris Button

I don't see how that matters. It has connections to other languages outside Lolo-Burmese.

Chris Button said,

June 20, 2024 @ 9:32 pm

Yes, and in Kuki-Chin, it's *ŋun but the tonal reflexes are inconsistent internally. You're dealing with a loanword.

Vampyricon said,

June 25, 2024 @ 10:49 pm

Just because the Kuki-Chin reflexes are loans doesn't mean the word isn't inherited in other languages.

Chris Button said,

June 26, 2024 @ 9:30 am

But as I said before, the Burmese form you cite is an isolate in Lolo Burmese. That means it doesn't exist in the other LB languages! There is too much special pleasing going on here with tones and all this -r/l/n stuff that is too often used as a wild card. Doesn't Sagart 1999 write something about a possible external source too?

Chris Button said,

June 26, 2024 @ 9:30 am

*pleading not pleasing