Stress timing? Not so much.

« previous post | next post »

This all started when John Cowan defended the New Yorker's account of a long-past Republican debate, by proposing that Rudy Giuliani retains the syllable-timed speech rhythm of his Italian ancestors, in contrast to Mitt Romney's standard American stress-timed speech. I didn't share the intuition, and did a little experiment to show that Rudy's syllables, far from being a "constant rate … dadadadadadada", were actually more variable in duration than Mitt's were ("Slicing the syllabic bologna", 5/5/2008).

Then Jonathan Mayhew asked whether "there’s a psychological perception of syllable-timed language that is not visible in the objective data". I responded with a little experiment to illustrate the fact that syllables in (say) Spanish really are closer to being constant in duration than syllables in English are, even though this is mostly if not entirely because of the intrinsic durations of the syllable inventories in the two languages ("Another slice of prosodic sausage" 5/6/2008).

But this leaves the "stress-timed" side of the traditional distinction unexamined. So today's little Breakfast Experiment™ takes a look at the idea that speakers of languages like English arrange stressed syllables (as opposed to all syllables) equally in time.

Let's start, as many good experiments do, with the conclusion. In English, the duration of syllables and other speech units depends mostly on five factors:

- The intrinsic timing of the gestures involved (e.g. the tongue-tip is a more agile articulator than the lips; it generally takes longer to open the vocal tract for a low vowel than for a high vowel, since more motion is required; etc.)

- Pre-boundary lengthening: a systematic rallentando at the ends of words and phrases (see "The shape of a spoken phrase", 4/12/2006).

- Stress and emphasis.

- Speaking rate (which can vary for many reasons).

- The real-time effects of composing and performing the message (e.g. slowing or pausing to think of what to say).

The influence of "stress timing", in the sense of an effort to space stresses equally in time, is normally negligible, indeed perhaps non-existent.

In order to illustrate this point, I recorded 32 phrases five times each, in random order. In this post, I'll look at four of these phrase types, and leave the rest as foils for now. (I might post about them another time — but they just basically illustrate the same ideas in different ways.)

First, I need to make a point about what to measure. In speech as in music, the representative time point of a region of time is obviously its beginning. Point-time events, like drumbeats, line up with the start of notes extended in time — from a flute, for example, or a singer. And if a half-note in one part corresponds to four eighth-notes in another, the start of the first eighth-note and the start of the half-note line up in time.

We can check the psychological alignment point for a spoken syllable or word by replaying it over and over in a regular pattern, and asking people to beat time; or we can play a regular beat, and ask people to repeat a given syllable or word in time with it. This is very easy to do, these days, given multi-track computer audio programs like audacity, which allow you to play one track while recording another.

Do this for a monosyllable in English, and you'll find that the line-up point is generally at or near the beginning of the open portion of the syllable. Do it for a polysyllabic word, and the alignment point will be near the release of the main-stressed syllable. In some sense, this is what it means for English to be "stress timed". (But not so fast — Spanish works pretty much the same way, in this respect!)

Consider the phrase "there's a bit of that there", as it might be said, pointing, in response to a question like "Have you seen any <whatever> in this room?" Let's focus on the three stressed syllables bit, that, and there, and the intervals between them:

There's a bit of that there

If English is really stress timed, then the "bit of that there" sequence should go something like this in musical notation:

And if we look at the average durations of the two inter-stress intervals, from the release of bit to the release of that, and from the release of that to the release of there, we see that the two intervals are almost equal, despite the fact that the first one contains two syllables ("bit of") while the second contains only one ("that").

In fact, the second inter-stress interval averages a little bit (about 7%) longer: 297.2 milliseconds vs. 278.8 milliseconds for the first one. So I made one syllable as long as two — does this mean that I was really performing something like the musical pattern above? Not necessarily, since the vowel of that is intrinsically longer than the vowel of bit.

Let's see what happens if we add some additional syllables between that and the following stress, say in the phrase "There's a bit of that in this drawer":

There's a bit of that in this drawer

If I'm really aiming at isochronous stresses, the sequence in red should now correspond to a musical notation like this:

To perform this isochronously, I could slow down the "bit of that" inter-stress interval, or speed up the "that (in this) drawer" interval, or both.

But in fact what happened was that the average duration of the first inter-stress interval stayed almost exactly the same, at 284.4 milliseconds, while the average duration of the second inter-stress interval lengthened to 535.4 msec.

OK, now let's try substituting two long syllables ("cartload") for the one short syllable "bit", giving up the phrase "There's a cartload of that there". You can probably guess the result: the "that there" inter-stress interval stays almost identically the same as in "There's a bit of that there", namely 291.2 msec vs. 297.2 msec, while the first inter-stress interval more than doubles, to 603.2 msec.

And by adding the fourth version, "There's a cartload of that in this drawer", we complete the paradigm:

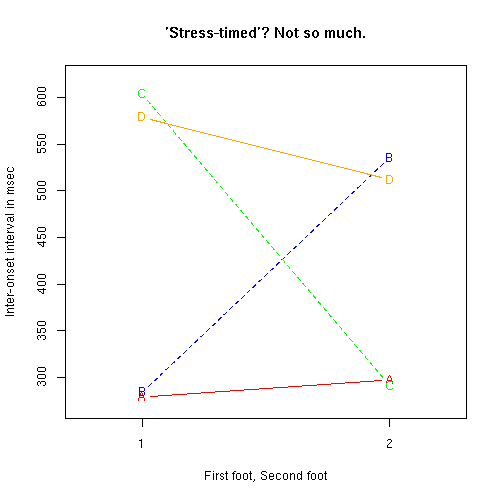

| Key | Interstress

interval type |

Phrase | Interstress durations

(mean) |

| A | short short | "There's a bit of that there." | 278.8 297.2 |

| B | short long | "There's a bit of that in this drawer." | 284.4 535.4 |

| C | long short | "There's a cartload of that there" | 603.2 291.2 |

| D | long long | "There's a cartload of that in this drawer" | 578.4 511.6 |

A plot makes the pattern clear. Each inter-stress interval basically retains whatever duration it intrinsically has, independent of the duration of of its neighboring inter-stress interval. To the extent that there's any hint of an effect here at all (and it's not statistically reliable), it's that the longer intervals are lengthened a bit when they're paired with shorter ones — which is anti-isochronous.

Some alert readers may be considering the hypothesis that my longer intervals are conceptually double the length of my shorter ones, so that I've maintained a sort of musical rhythm, just not one in which all of the (underlyingly isochronous) beats are realized.

That's what the other 28 sentences in the experiment were for. If I had time to go over them, we'd see that there's no stable quantization of time — no objective "meter" — that underlies normal speech timing in English. (Well, at least not in my performance in this recording; but larger-scale ways of approaching the same question lead to the same conclusion.) In experiments like this one, the null hypothesis is that the timing of speech units is not affected by changes in the timing of the units around them — and in general, as long as we control for the five factors cited at the start of this post, the null hypothesis stands up pretty well.

That doesn't mean that stress is not an organizing principle in English prosody. On the contrary, I argued long ago that English stress is really just a sort of symptom of a psychologically-real prosodic organization, and I'm still inclined to think that this is true. But the prosodic structures in question aren't normally performed in such a way as to space stressed syllables at equal intervals of time.

An analogy may help to make the point. Gait — walking or running — is obviously rhythmic, And the time intervals between steps are normally equal. But suppose you put a weight on one ankle. Now the steps will still follow one another regularly, but they'll no longer be equal in time. You've changed the dynamics of the system, and as a result, strides with the weighted ankle will be slower, unless you walk very slowly and try very hard to make the strides equal.

When you talk, the motions that you make with your lips, jaw, tongue, velum and larynx have very different intrinsic dynamics, due to differences in the mass of the articulators being moved, the muscle forces available, and the distances to be traveled. So even if speech were as straightforwardly rhythmic as walking or running, we wouldn't expect the units to unfold in equal amounts of time. (The influences of phrasing, emphasis, thinking-time etc. take us even farther from isochrony.)

In fact, even when English speakers try to emphasize the stress-rhythm of their speech, the result can sometimes be paradoxical — the inter-stress intervals may become less equal rather than more equal. But that's an experiment for another morning.

Rick S said,

May 8, 2008 @ 11:56 am

It's not clear to me that you've controlled for the possibility that a (theoretical) psychological drive toward stress-timed speech influences word choice and phrasing. That is, "There's a bit of that there" might be more common than "There's a bit of that over there", while "There's a cartload of that over there" outnumbers "There's a cartload of that there" in the corpora.

I realize this was just a Breakfast Experiment, and that detecting such an influence could well be too large an undertaking for such, but isn't this a valid consideration? BTW, I have no attachment to the stress-timed hypothesis; this is just my curiosity.

Jonathan said,

May 8, 2008 @ 11:57 am

Wikipedia claims that Mexican Spanish is stress-timed, citing vowel reductions, but it would seem that the whole notion is not that solid. On the other hand, the notion of syllable-timing is a little more defensible, if the "intrinsic duration" of syllables in a given language tends toward equality.

Timothy M said,

May 8, 2008 @ 11:53 pm

So what about so-called "mora-timed" languages? Do they really follow temporal patterns that they're said to follow? It's an interesing question for me, as someone who studies Japanese, which is said to be mora-timed. I do intuitively notice timing differences between English and Japanese, although whether they're actually the result of all morae getting an equal amount of time, I cannot say.