What is the logical form of that?

« previous post | next post »

This post wanders down a series of rabbit holes, from a couple of dead economists, to a dead philosopher, to a dead Supreme Court justice. It all started with Eric Rahim's obituary in the Guardian, which links to the British Academy's obituary for Piero Sraffa, which includes this passage:

This post wanders down a series of rabbit holes, from a couple of dead economists, to a dead philosopher, to a dead Supreme Court justice. It all started with Eric Rahim's obituary in the Guardian, which links to the British Academy's obituary for Piero Sraffa, which includes this passage:

He also formed a close friendship with the Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, the founder of linguistic philosophy, who was a Fellow of Trinity College and later became Professor of Philosophy at the University. They met regularly on afternoon walks and engaged in endless discussions during the time that Wittgenstein prepared his second book entitled The Nature of Philosophical Investigations, in which he considerably modified his original position put forward in his first book, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. In the introduction to the later work Wittgenstein paid the most generous tribute to Sraffa's unceasing interest in philosophical problems and to his capacity and readiness to engage in endless discussions. He stated in the Introduction to his second book (translated from the German original) that 'it was this stimulus to which I owe the most momentous ideas of this book' (italics in the original).1

1It was a question of Sraffa's which convinced him that language and reality do not necessarily have a common logical form.

Wondering what that "question of Sraffa's" was, I skimmed Sraffa's Wikipedia article, which led me in turn to Norman Malcolm, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir, which repeats the claim:

Of great importance in the origination of Wittgenstein's new ideas was the criticism to which his earlier views were subjected by two of his friends. One was Ramsey, whose premature death in 1930 was a heavy loss to contemporary thought. The other was Piero Sraffa, an Italian economist who had come to Cambridge shortly before Wittgenstein returned there. It was above all Sraffa's acute and forceful criticism that compelled Wittgenstein to abandon don his earlier views and set out upon new roads. He said that his discussions with Sraffa made him feel like a tree from which all branches had been cut. That this tree could become green again was due to its own vitality. The later Wittgenstein did not receive an inspiration from outside like that which the earlier Wittgenstein obtained from Frege and Russell.

And later gives details, including two (similar) versions of the question itself:

Wittgenstein related to me two anecdotes pertaining to the Tractatus, which perhaps I should record, although he also told them to several other persons. One has to do with the origination of the central idea of the Tractatus-that a proposition is a picture. This idea came to Wittgenstein when he was serving in the Austrian army in the First War. He saw a newspaper that described the occurrence and location of an automobile accident by means of a diagram or map. It occurred to Wittgenstein that this map was a proposition and that therein was revealed the essential nature of propositions-namely, to picture reality.

The other incident has to do with something that precipitated the destruction of this conception. Wittgenstein and P. Sraffa, a lecturer in economics at Cambridge, argued together a great deal over the ideas of the Tractatus. One day (they were riding, I think, on a trains when Wittgenstein was insisting that a proposition and that which it describes must have the same 'logical form', the same 'logical multiplicity', Sraffa made a gesture, familiar to Neapolitans tans as meaning something like disgust or contempt, of brushing the underneath of his chin with an outward sweep of the finger-tips of one hand. And he asked: 'What is the logical form of that?' Sraffa's example produced in Wittgenstein the feeling that there was an absurdity in the insistence that a proposition and what it describes must have the same 'form'. This broke the hold on him of the conception that a proposition must literally be a 'picture' of the reality it describes.3

3 Professor G. H. von Wright informs me that Wittgenstein related this incident to him somewhat differently: the question at issue, according to Wittgenstein, was whether every proposition must have a 'grammar', and Sraffa asked Wittgenstein what the 'grammar' of that gesture was. In describing the incident to von Wright, Wittgenstein did not mention the phrases 'logical form' or 'logical multiplicity'.

Having somehow missed these stories, I previously assumed that Wittgenstein's intellectual evolution had something to do with other aspects of his post-Tractatus life experiences, such as working as a gardner and teaching elementary school. I guess it makes sense that he was more willing to listen to an economics professor than to a bunch of Austrian schoolchildren, though they must have exhibited implicitly similar arguments.

In that connection, we should discuss the absurd textual fixation of (many if not most) linguists and psychologists, who study "language learning" and "communication" and "pragmatics" with little or no attention to non-lexical aspects of speech, much less to gesture, posture, and facial motions. More on that, maybe, some day…

Meanwhile, a bit of chin-flick background:

"Everything is too appropriate these days", 4/5/2006

"Adam Kendon on the 'chin flick'", 4/7/2006

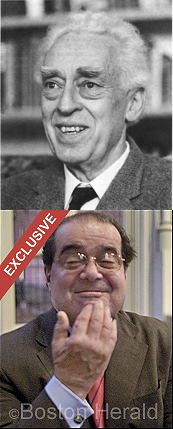

"Antonin and Beppe", 3/4/2014

Update — I should repeat, and emphasize, Adam Kendon's note about the (locally variable) "meanings" of the chin-flick:

[A]s I say, in regard to language, as well as gesture, you cannot generalize about "Italians" — you have to be local.

Cervantes said,

June 8, 2023 @ 9:27 am

In any case, the entire discussion is feckless because speech creates reality, it doesn't just represent it. Language doesn't, for the most part, consist of propositions at all.

AntC said,

June 8, 2023 @ 9:54 am

Thanks Mark. I was an undergraduate in Philosophy in mid-70's (at a newly-built University) when W's later works were being slowly absorbed by the establishment.

We had one keen lecturer just completing his Doctorate on W who seemed on another planet as compared with a Logical Positivist desperately trying to win tenure back at Oxford.

The most critical example I remember was the duck-rabbit. If a proposition is a picture [per the Tractatus], what logical form does a duck-rabbit depict? This is posing the same challenge as Sraffa's gesture — but without the need to explain to British undergrads some obscure semiotics, laboring over which would make the whole thing fall flat.

It's at least possible the Austrian school kids taunted their gawky teacher with such puzzles.

Gestalt psychology would be by then getting popularized over the Positivists' "atomism". (Not that W ever subscribed to that.)

AntC said,

June 8, 2023 @ 10:27 am

Sraffa asked Wittgenstein what the 'grammar' of that gesture was.

All languages have exclamations (like 'yeuch!') that follow the phonology but aren't words as such. Aren't they counterparts to gestures?

In a post-W world they'd be Performatives. They're just as much subject to pragmatics of usage and context.

Peter Grubtal said,

June 8, 2023 @ 10:48 am

When we're on Wittgenstein and gestures, surely the poker incident must figure.

A large part of what I know, (and respect ) about philosophy comes from Popper.

gds555 said,

June 8, 2023 @ 2:52 pm

Just as a side-note, I think it’d be fair to say that the Tractatus author’s twice-mentioned fondness for “endless discussions” demonstrates that brevity was not the soul of Wittgenstein.

JPL said,

June 9, 2023 @ 6:27 pm

I guess you must know about the U. of Chicago psychologist of language David McNeill, who did an extensive exploration of the relations involving language, gesture and thought, and has several books on the topic, the most recent of which would be How Language Began: Gesture and Speech in Human Evolution (2012). The area of his research that I found most interesting was his study of the gestures mathematicians use when they are talking about mathematical problems and describing abstract mathematical objects, operations and relations, which included an abundant output of video recordings. The interesting question he was pursuing concerned whether there were equivalences in logical form between the gestures and (otoh) the abstract mathematical ideas they were talking about, including metamathematical descriptions and the meanings of the formal language expressions they were doing their mathematical thinking in. (I'm not sure he expressed it just like that, but that's how I took the problem he was pursuing. I'm not sure whether or not he ended up sufficiently distinguishing the roles of the gestures, linguistic expressions (both natural language and formal language), and mental images as signifiers allowing alternative expression of a single mathematical "thought" being expressed, which would have the logical form of interest on the side of meaning. If he did, that's great, I haven't read the later work.)

As for Sraffa's question about the logical form of the Italian chin flicking gesture, that's a question I would think the mathematician/physicist named Dr Armstrong whose whimsical article about "inference sabotage" you posted about some time back (8Apr or thereabouts?) would be able to offer an answer to.

Wittgenstein's question about the logical form of the proposition and its relation to reality, and a speaker's understanding of reality, is an even bigger interesting question. This sentence from David Bell (in Frege's Theory of Judgement, p. 1), which I will just quote without context, seems pregnant with possibilities on that question: "Judgement … is the primordial act in terms of which we make sense of the world." (For "judgement" in this case we can substitute the referentially equivalent expression, "formulating a proposition".)