Of reindeer and Old Sinitic reconstructions

« previous post | next post »

This is a piece that I've been meaning to write for a long time, but never found the opportunity. Now, inspired by the season and about to embark on extended holiday travel, I'm determined not to put it off for yet another year.

The genesis of my ruminations on this topic are buried in decades-old tentative efforts to identify the fabulous creature known in Chinese myth as the qilin (Hanyu Pinyin), also spelled as ch'i2-lin2 (Wade-Giles Romanization) and kirin in Japanese, which the whole world knows as the name of a famous beer (fanciful, stylized depictions of the kirin are to be found on bottles and cans of the beer).

The qilin is usually referred to in English as a kind of unicorn, but I knew that couldn't be right, since no account of the qilin from antiquity describes it as having only one horn. The Chinese xièzhì 獬豸 ("goat of justice") does have a single, long, pointed horn, but that is another matter, for which see "Lamb of Goodness, Goat of Justice" (pp. 86-93) in Victor H. Mair, "Religious Formations and Intercultural Contacts in Early China," in Volkhard Krech and Marion Steinicke, ed., Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe: Encounters, Notions, and Comparative Perspectives (Dynamics in the History of Religion, 1 [Ruhr-Universität Bochum]) (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 85-110 (available on Google Books). Since customs pertaining to the goat of justice, as with the reindeer, existed in cultures spread across northern Eurasia, I suspect that an extra-Sinitic loanword may also be lurking behind xièzhì 獬豸.

The earliest references to the qilin are in the 4th-century BC Zuo Zhuan (The Zuo Tradition).

For previous Language Log posts about reindeer, see:

"Reindeer talk" (12/24/13)

"Reindeer lore " (12/8/16) — includes 95 comments with words for reindeer in different languages, plus descriptions of customs and culture concerning reindeer.

I will not repeat here the abundance of materials and references concerning reindeer that are readily available in those posts. Here I wish primarily to focus on the morphology and phonology of the Sinitic word qilin and discuss its possible relationship to the IE word "reindeer".

What led me to draw this parallel in the first place? Qílín is one of those Old Sinitic disyllabic morphemes, of which there are a considerable number. See:

"GA" (8/6/17)

"'Butterfly' words as a source of etymological confusion" (1/28/16)

So, when the word was first written down, neither of the two characters chosen to represent its sounds in Sinitic had a meaning of its own. Qilin may be written either with a cervid radical, thus 麒麟, or an equid radical, thus 騏驎. Early descriptions and depictions of the qilin represent it as having branching horns, so that fits well with the cervid orthographical form, and it is indeed the usual way to write qilin in characters. Horses do not have horns, of course, but the mythological descriptions of the creature occasionally do have equid characteristics. Furthermore, as Kristen Pearson has shown in her remarkable "Chasing the Shaman’s Steed: The Horse in Myth from Central Asia to Scandinavia" (free pdf), Sino-Platonic Papers, 269 (May, 2017), 1-21, the people of the steppes often outfitted their horses with deer antlers and other cervid attributes (see also the lengthy observations of Pita Kelekna below). This is a key point and indicates the great reverence that people of the steppes had for deer, undoubtedly because they were important for their subsistence.

When the ancient Chinese said they were "waiting for the unicorn", it signaled something of great auspiciousness, perhaps the advent of a good ruler. Moreover, the unicorn was said not to be indigenous to the Middle Kingdom. Based on early texts, this is documented in Bryan Van Norden, Confucius and the Analects: New Essays (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 139-142. Confucius, who perhaps was hoping to be identified as the longed for sagely ruler, was deeply disappointed when a (qi-)lin was captured by persons who did not recognize its true significance.

Occasionally the first character of 麒麟 / 騏驎 is omitted, leaving just 麟 / 驎. In essence, this is simply an elision of the onset (anlaut), hence lin / rin.

So much for the morphology and semantics of qilin, at least for the present moment. How about the phonology? Just judging from the Japanese phonology, which adheres to Middle Sinitic norms far more closely than Mandarin, I had always felt that the undimidiated form of kirin would have been something like krin or hrin. That right away made me think of the "rein-" of "reindeer" (the "-deer" part I suspected was either redundant or simply there to indicate that it was a "rein-" type of "-deer", but when I first started looking into this I couldn't find any Old Sinitic (OS) reconstructions that were encouraging in that direction. More recently (a couple of years ago), however, I discovered that Zhengzhang Shangfang reconstructed MSM qílín 麒麟 as OS *g(ɯ)-rin. (I could not find the word in Schuessler's Etymological Dictionary (2007) or in Baxter and Sagart's 2014 book on Old Sinitic.)

Zhengzhang's reconstruction as *g(ɯ)-rin gave me a shot of adrenalin and spurred me forward.

Next, I had to look at the etymology of "reindeer". Here's what is given in Wikipedia:

The name rein (-deer) is of Norse origin (Old Norse hreinn, which again goes back to Proto-Germanic *hrainaz and Proto-Indo-European *kroinos meaning "horned animal").

The word deer was originally broader in meaning, but became more specific over time. In Middle English, der (Old English dēor) meant a wild animal of any kind. This was in contrast to cattle, which then meant any sort of domestic livestock that was easy to collect and remove from the land, from the idea of personal-property ownership (rather than real estate property) and related to modern chattel (property) and capital. Cognates of Old English dēor in other dead Germanic languages have the general sense of animal, such as Old High German tior, Old Norse djúr or dýr, Gothic dius, Old Saxon dier, and Old Frisian diar.

Basically, when I'm trying to compare "reindeer" and "MSM qílín < OS *g(ɯ)-rin, I can disregard the "deer" part, because that is an add-on to reinforce the fact that the "rein-" ("horned animal") is indeed a "-deer" ("animal"). Thus the "rein-" part by itself signified the animal in question, and the other Germanic word, the "deer" part, was added relatively late in the history of the word.

And how did the word "reindeer" come into English?

Juha Janhunen reexamines some of the evidence adduced above and introduces words for reindeer from non-IE languages:

The English word reindeer is composed of two elements, rein, which originally means 'reindeer', and deer, which originally means 'animal'. In modern Swedish, for instance, these meanings are still preserved: ren 'reindeer', djur 'animal'. In German, a folk etymology has given the form Renntier, as if it was 'running animal', from rennen 'to run' and Tier 'animal'. (A similar folk etymology is Maultier for 'mule', as if it was from Maul 'animal's mouth' + Tier 'animal'.)

The Saamic languages (c. 10 of them, of which Northern Saami is the most spoken today) have an extensive reindeer vocabulary, with items for different types, sexes, ages, colours, and parts of the animal. You can find a complete reindeer terminology (in Northern Saami) in the Saami (Lappish) Dictionary of Konrad Nielsen (3 vols., I think the reindeer terminology is in vol. 3). The general word for domestic reindeer in Saami is (Northern Saami) boazu (: genitive bohcco), which would presuppose a Proto-Saami shape like *poco. This has been compared with Finnish poro 'reindeer', though the consonant correspondence *c : *r is not regular. Finnish also has a separate word for wild reindeer, which is peura < *petra, also present in Estonian pôhjapôder = 'northern deer', from pôhja- (gen.) 'of the north' and pôder 'deer'.

Needless to say, all Siberian languages spoken by populations dealing with reindeer breeding in different forms have a likewise developed reindeer terminology. For instance, Tundra Nenets is the only Uralic language which has a native word for 'thousand', Tundra Nenets yonar. This is because the word originally means 'a flock of one thousand reindeer'. The Nenets, like other Tundra peoples, can own domestic reindeer in the thousands, while the forest peoples normally have only up to 50 reindeer per family. The flocks of wild reindeer, as on Taimyr Peninsula (and also in Alaska) can, of course, comprise thousands (totally hundreds of thousands) of animals.

Samoyedic (a branch of Uralic, which also comprises Nenets) has a word for 'reindeer' which seems to go back to Proto-Samoyedic, a language that was spoken in Southern Siberia around year zero. This – the Upper Yenisei basin and the Sayan mountains – is the region where the reindeer was probably first domesticated along the patterns already known from horse domestication. It seems that the Samoyedic word *cë(x) was also borrowed into Mongolic, where reindeer is caa or caa bugu (with bugu 'deer'). Turkic languages have no primary word for the reindeer. In Yakut, for instance, reindeer is taba, which is the Turkic word for 'camel'.

Laila Williamson wrote an MA thesis on reindeer in 1974. She recalls that the Finnish word for reindeer is poro, female is vaadin, calf is vasa, male is hirvas and castrated male is härkä. In Swedish reindeer is ren [VHM: once again N.B.].

Returning to Germanic terms for "reindeer", Donald Ringe states:

It's true that the -deer part was added later; in the only Old English text where the animal is mentioned, they're just called hra:nas (I'm using the colon to indicate vowel length here). However, it looks like OE hra:nas is basically a loan from ON hreinn, pl. hreinar made by someone who knew both languages well enough to figure out what the word "should" look like in OE. Otherwise the ON word has no cognates in other Gmc. languages, so you can't project "*hrainaz" back into PGmc. unless there are outside cognates–and there are not; nothing like "*kroynos" appears anywhere else, and *-oyno- is not a suffix that appears in other words. It does look like the ON word might be a formation ultimately related to the "horn"-words, but that's as much as can be said.

Pita Kelekna, author of the The Horse in Human History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), which I will refer to as HHH below, adds the interesting fact that the reindeer is a European semi-domesticated caribou, which is milked by Sami / Lapp women. She also dug up this bit of Word Lore:

Pita comments:

If in fact 'krei' is proto-IE, that might tend to validate archaeological assertion of reciprocal river trade between southerly steppe agro-pastorialists and northerly boreal-forest inhabitants.

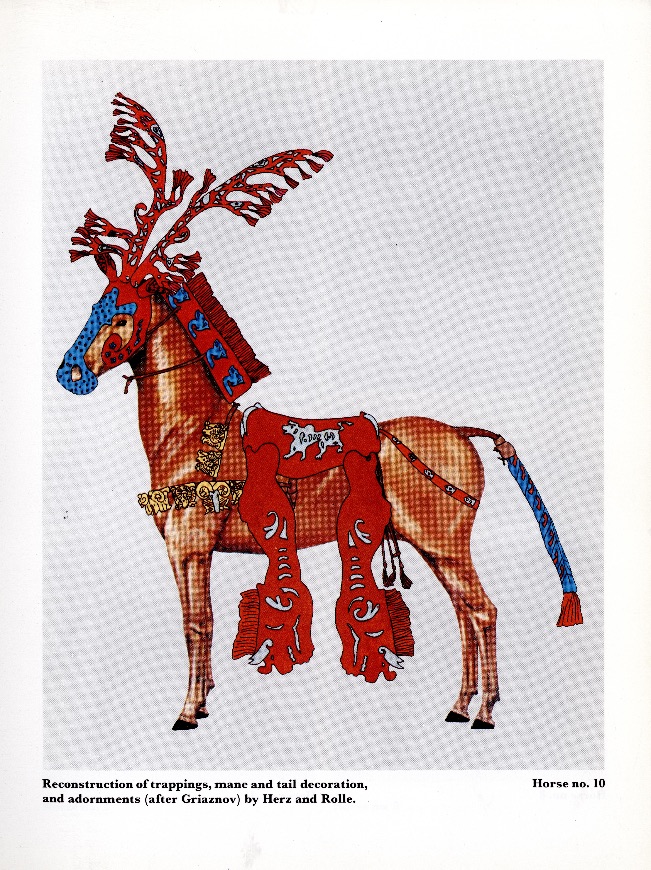

The paperback version of Pita's book (HHH) has on its front cover a very fine image of Renate Rolle’s exceptional restoration of the Pazyryk tomb No. 10 antlered horse, which she discusses in some detail in the section "The Horse — Sacred Symbol of Rebirth", p. 78. The reconstruction of the antlered horse in Pazyryk tomb No. 10 is the source of the colored drawing above.

The Pazyryk culture is a Scythian nomadic Iron Age archaeological culture (c. 6th to 3rd centuries BC) identified by excavated artifacts and mummified humans found in the Siberian permafrost, in the Altay Mountains, Kazakhstan and nearby Mongolia.

More on steppe reindeer and horse representations and beliefs from Pita Kelekna:

What I remember most of Esther Jacobsons’s The Deer-Goddess of Ancient Siberia (1993 Brill) is her repeated assertion that in early hunting/gathering days the female elk was a primordial cosmic mother symbol which, with time as subsistence strategies shifted, transitioned into first the deer, then the composite antlered horse. There is nothing particularly surprising about this, of course, in that something rather similar happened in the New World, where for some 4,000 years the horse served simply as a food animal. Only with the escape and proliferation of the Spanish domesticated horse onto the prairies and pampas, did the horse there escalate into the warhorse, the pomp and magnificence of which were elaborately reflected in many different art forms. One area in which I disagree with Jacobson is her insistence that deer stones or reindeer stones as they are sometimes called (because often they are adorned with images of both deer types) are not phallic. Admittedly, I have not done extensive ethnographic fieldwork in Mongolia / Siberia and the stones are more jagged than tapered, but I suspect that the deer stones are the male counterpart of the cosmic female (ambisexual) goddess of procreation, marking success in the hunt—also equated with warring exploits and celebrated in funerary ritual.

I thought to bring your attention to another, more recent, Jacobson book, The Hunter, the Stag, and the Mother of Animals: Image, Monument, and Landscape in Ancient North Asia (Oxford 2015 ISBN: 9780190202361) written in conjunction with her photographer-husband, Gary Tepfer. There are many marvelous representations of steppe animals. In one of them, note the lion’s tail of the composite animal, obviously showing Iranian influence. Reference: Rolle, Renate 1980 Die Welt der Skythen (Luzern und Frankfurt FM: Verlag C. J. Bucher); published in English 1989: The World of the Scythians (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1989).

I briefly met Jacobson once at the Metropolitan. She has spent a great deal of time in the Altai and, in her analysis of early steppe art, she identifies an ancient cervid goddess, the female elk, as the embodiment of the forces of rebirth and regeneration. Across millennia, to accommodate the inflow of new cultural elements, this image shifted to syncretic form (Jacobson 1993:3, 92), as over time, the elk was replaced as the source of life and guardian of death by the deer, ambi-sexed, its rack of antlers swept back in great waves over its lithe body (Jacobson 1993:20). Focal symbol of cosmogenesis, the deer’s branched antlers, often foliate in shape surmounted by birds, formed the tree of life (Jacobson 1993:85–87). As equestrian nomadism supplanted hunting, the composite image of the deer-horse emerged (Jacobson 1993:4), the deer acquiring the long equine torso, the horse the deer’s towering antlers. The horse became the cosmic animal, associated with gold, the sun, and the heroic warrior. Chariot and wheel, emblematic of the sun disc, furnished the vehicle of the gods (Jacobson 1993:129–131). Intertwined with antler and tree-of-life metaphor, the horse served as the steed on which the dead made their journey to the next world (Jacobson 1993:86) and was an integral component of steppe funerary observances. The early steppe themes and imagery of death and rebirth, together with the concept of the horse as a cosmic symbol, would persist across Eurasia to shape the religions of Hinduism and Buddhism and would also extend westward through Zoroastrianism to influence Greek mythology, Christianity and Islam.

Prominent throughout Vedic ritual, the horse is seen as instrumental in the acquisition of secret knowledge, the horsehead revered. In the Rgveda, Indra revealed the sacred mysteries of honey mead (madhu) distillation to the fire-priest Dadhyanc, engaged in devout prayer and meditation. But the god threatened to decapitate Dadhyanc, should he divulge this information to any other. The divine Asvin twins, desirous of learning the secret, pled to be Dadhyanc’s pupils and promised to protect him by cutting off his head and replacing it with a horsehead, at which point Dadhyanc imparts the secret knowledge. The god then cuts off the horsehead for which the twins substitute Dadhyanc’s real head (Singh 2001:152–153). At Chibarnalla, also evident amidst images of horses and chariots was a sun-headed man with a bow shooting at the enemy – the ancient Aryan sun-god Mithra. And the Rgveda, Book 1, CLXIII, explicitly connects the horse to the deer, stating the horse has horns. Verse 9: “Horns made of gold hath he.” Verse 11: “Thy horns are spread in all directions.” (tr. Griffith 1889 cited by Mair 2007:43n). In Greece, the winged white stallion Pegasus bore the Greek hero Bellerophon aloft in order to defeat the monstrous chimera. Similarly, on his miraculous Night Journey Mohammed mounted the winged white horse Buraq to ascend through the seven levels of heaven to speak with Allah, Moses and Christ.

Much of ancient sacred steppe lore had been incorporated into shamanic ritual observances, in which mythology reflected the complex interaction between the forces of nature, men, and the supernatural. These beliefs were given visible form in flourishing ornamentation in which zoomorphic imagery was paramount, an art form known to our modern world as “animal style” The motif of animal combat or predation has been interpreted by Rudenko as reflecting the all-pervasive, dualistic struggle between good and evil as propounded in Persian Zoroastrianism. Depiction of ferocity and death was juxtaposed with birth and life. Many images clearly evoked fertility and procreation, with ithyphallic features and popular themes of animal copulation to celebrate the cyclic rhythms of death and rebirth.

I was interested to read Pearson’s treatment of Odin/Yggdasil. Indeed, just as the domesticated horse and metallurgy diffused west from the Pontic-Caspian, so Proto-IE evolved and diversified into the more recent IE languages; along with these developments, early steppe cosmic beliefs penetrated Europe. The same thing is true at the eastern end of Asia, as c.13000 BP ancestors of Amerindians traversed Beringia, carrying Asian shamanic beliefs into the New World. Over the last few decades of Anthropological Meetings, I have attended more sessions addressing parallels in Asian and Amerindian shamanism (generally North American) than I care to recall—and of late, parallels between North/South American shamanism, which are multitudinous! By contrast, African and Australian primitive religions are starkly different. This past Friday, in fact, Sikkim Kut (Korean Ritual of the Dead) was celebrated at the Asia Society in NYC, in which I observed three hours of shamanic song, dance, and instrumental music, much of which, in terms of cadence of chant, sound effects, and other dramatizations, was strikingly similar to the shaman’s curing sessions I had witnessed in the Amazon. Essentially, the shaman is intermediary betwixt and between: good and evil, sky and earth, supernatural and mundane, life and death, curing and malign sorcery. His animal associates, fantastic or natural, are his helpers whose powers he appropriates and directs. The shaman’s enigmatic character, transitional and transformative, is superbly represented in the fluid sacred imagery of the steppe’s Animal Style art.

[VHM: parenthetical citations may be found in HHH]

Further details of what Pita has written here may be found in the following sections of HHH: "The Horse – Sacred Symbol of Rebirth", (p.78), "Steppe Kurgans and Ritual Burial" (p. 79), "Regalia of the Pazyryk Kurgans" (p. 82), as well as her treatment of Elena Kuzmina's Andronovo material (p.55).

Tomorrow night, when you see Rudolph and his companions pulling Santa's sleigh through the sky, you'll know something of their pedigree.

Readings

- “Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions” (3/8/16)

- “Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 2” (3/12/16)

- “Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 3” (3/16/16)

- “Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 4” (3/24/16)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 5" (3/28/16)

- "Of armaments and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 6" (12/23/17)

- "Of shumai and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (7/19/16)

- "Of felt hats, feathers, macaroni, and weasels" (3/13/16)

- "GA" (8/6/17)

- "Of dogs and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (3/17/18)

- "Of ganders, geese, and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (10/29/18)

- "Eurasian eureka" (9/12/16)

- "Of knots, pimples, and Sinitic reconstructions" (11/12/18)

- "Of jackal and hide and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (12/16/18)

For all manner of lore about "The Mythic Chinese Unicorn", see Jeannie Thomas Parker's monograph with that title.

Beautiful photograph of a Kirin Chinese restaurant in Honolulu. From Nathan Hopson.

And here is a news article about a ninth-grade student in Taiwan who made an amazing model of a qilin / kirin with balloons (includes photograph). From Chau Wu.

[Thanks to Laila Williamson, E. Bruce Brooks, and A. Taeko Brooks]

Tom Dawkes said,

December 23, 2018 @ 3:29 pm

See also the Oxford English Dictionary's entries for

— reindeer at http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/161586?redirectedFrom=reindeer#eid

and

— rein [2] at http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/161561#eid26256564 and

maidhc said,

December 23, 2018 @ 6:43 pm

Very interesting.

Why is Kirin a name for a Chinese restaurant? There are at least four in the SF Bay Area, three in Vancouver BC, one in London UK and one in Hawaii.

I couldn't find any that had the name in Chinese that I could cut and paste, but these are the closest.

https://www.thekirin.com/

http://www.kirinrestaurants.com/

I would expect Kirin to be a Japanese restaurant and a Chinese one to be Qilin or Chilin. (The Kirin in Lindenhurst NY is both Chinese and Japanese. The Kirin in Tulsa OK is pan-Asian but has a lot of sushi.)

Is it just that Kirin is easier for people to pronounce because of the beer? I've only been to the Kirin closest to home. It's the kind of place where they have a lot of menu items handwritten on sheets of paper stuck up on the walls, and only in Chinese, no translation. So evidently a lot of their customers can read Chinese.

Chris Button said,

December 23, 2018 @ 11:01 pm

Nice! I wonder if the velar component of 麒 before the root 麟 is reflective of the original velar in PIE *krei-? Alternatively, perhaps Houghton's "velar animal prefix" originally coming from Austroasiatic has been added to what was originally an Indo-European root to create a Sinitic word!

stephen said,

December 23, 2018 @ 11:23 pm

Here's a more recent article about the Elasmotherium. It could have survived to recent times, after all.

https://www.wired.co.uk/article/unicorns-are-real-kind-of

Until now it was thought the ancient animal died out too far too early — around 350,000 years ago — to persist in human memory or oral history. But new research suggests that it actually persisted in Kazakhstan until around 29,000 years ago, which means that its lifespan overlapped with that of modern humans. The study from Tomsk State University, published in the American Journal of Applied Sciences, details new fossil evidence of the Elasmotherium sibiricum, which could be up to 9,000lbs in weight.

And there used to be a constellation of the reindeer.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rangifer_(constellation)

Andreas Johansson said,

December 24, 2018 @ 1:55 am

If the IE word is unknown outside of North Germanic, how is it supposed to have made it's way to China?

stephen l said,

December 24, 2018 @ 3:37 am

my chinese dictionary (https://cc-cedict.org/editor/editor.php) gives "麒麟" as mythical chinese unicorm, but gives "mythical male unicorn" for 麒 and "female unicorn" for 麟 (along with allowing both individually to stand for 麒麟).

Sean M said,

December 24, 2018 @ 4:47 am

Andreas: thanks to Icelandic literature, we know more about names for wild animals in Proto-Germanic than we do about them in other Indo-European languages close to reindeer habitat. I guess an identifiable word for reindeer might show up by chance in Avestan or Tocharian but I would not expect it in the kinds of texts that record Sogdian or Pahlavi, and we know so little about what the Saka/Scythians spoke …

David Marjanović said,

December 24, 2018 @ 4:53 am

But what is this strange *ker-j- thing that none less than Ringe has apparently never heard of?

Note that Prof. Mair never says it did. He just presents the two words and conveys excitement about them, that's all.

Now, if Uralic and Tungusic had similar words for "reindeer", that would help; but AFAIK they don't.

David Marjanović said,

December 24, 2018 @ 5:05 am

Do we? Even if Ringe is wrong above and OE hrānas (pl.) is a real cognate of ON hreinn (sg.) rather than etymologically nativized, that only gets us to Proto-Northwest-Germanic and not to Proto-Germanic. What if it was borrowed from one of whatever languages the Scandinavian hunter-gatherers spoke before the Sámi came in?

This is an old, venerable, and desperate attempt to attempt every one of the rare disyllabic words as a compound. It's most likely wrong.

Michael Watts said,

December 24, 2018 @ 7:20 am

He says a bit more than that:

For there to be a possible relationship, the same word would have to travel to both groups/places.

Sean M said,

December 24, 2018 @ 7:41 am

David Marjanović: since my field is Altorientalistik not Indogermanistik I can't comment on the details of the etymologies, but as far as I know Old Norse is the Indo-European language spoken near the boreal forest which has left us the biggest vocabulary for plants and animals to explore for Proto-Germanic and Proto-Indo-European roots. If this were about words for "horse" or "barley" then I would expect to see more discussion of languages further east.

I read this series of posts as toying with intriguing possibilities not claiming to have strong evidence.

Chris Button said,

December 24, 2018 @ 7:52 am

@ David Marjanović

Calvert Watkins treats *krei- as an extended form of kʲer-.

Boodberg proposed "dimidiation" back in the 1930s.

Sean M said,

December 24, 2018 @ 7:55 am

Also, I am taking it for granted that Professor Mair has not found any other word for "reindeer" firmly attested in early Indo-European languages, or else he would highlight that and explain why he nevertheless thinks that the Old Norse word has a PIE ancestor with the same meaning. I do not have time on Christmas Eve to go read the comments on the old Language Log post he links to.

Jichang Lulu said,

December 24, 2018 @ 10:11 am

As kVrV- / gVrV- animals go, there is Mongolian гөрөөс göröös (trad. script görögesü), used as the second half of the name of various deer-like animals, and Korean gorani 고라니, the water deer.

Penglin Wang said,

December 24, 2018 @ 5:05 pm

It is beyond question that Indo-European vocabulary diffusion had reached Inner Asia including its easternmost part. In the case of cervid terminology, I had a poster presentation at a conference and would like to paste its abstract here to supplement Professor Mair’s approach to the Chinese qilin.

71st Annual Northwest Anthropological Conference

Boise State University & the Idaho State Historical Society

Boise, Idaho, March 28-31, 2018

Cervidae Ethnonyms in Inner Asia

(Poster Abstract)

Penglin Wang

Department of Anthropology and Museum Studies

Central Washington University

wangp@cwu.edu

Included in the fauna of Inner Asia is a wide variety of deer, such as antelope, gazelle, roe deer, and elk or moose. This diverse cervid species serves as reservoir of food and fur supply. For millennia, early humans in Inner Asia had been chronic achievers in rock art. In Mongolia Altai and Inner Mongolia Yin mountain ranges there where rock drawings are found, there exists a long-standing connection between appreciably artistic gratifications and an animal motive. Rock artists took interest in representing animals including deer and elk, reflecting people’s zoographic fondness, which could feed into nomenclature. In this presentation I focus on the ethnonyms Qarta’an, Hart, and Bugu, which derived from Cervidae terminology. I argue that Qarta’an and Hart came from Old English heort ‘hart,’ which was in turn diffused into Manchu a kandagan (< *karda-gan) and Mongolian as qandağai ‘Manchurian moose,’ and Bugu or Pugu (僕骨) from Turkic and Mongolic buğu and Manchu buhū ‘deer,’ which has an etymological connection with Sariqul (an eastern Iranian language) bɯǧɯi ‘deer.’ During the Sui-Tang dynasties (581-907), there were multiple tribes in the Turkic ethnicity in Inner Asia, especially in Mongolia, of which one tribe situated north of the Tuul River as a member of the Tiele confederacy was named Pugu. A set of ethnonyms or toponyms in the forms of Hart, Harta, Hartar, Hartagin, and Qarta’an were attested in Chinese and Mongolian sources in the main, and their alphabetical and Chinese transcriptions indicate clearly, these names are at the level of the root morpheme hart(a)- or qart(a)-, which is the same as English hart. And the additional root-final vowel a and the suffix -gin or -’an (< -ğan) resulted from the local Altaic speakers’ adjustment to their speech.

Please note that the initial fricative h- of Old English heort ‘hart’ was represented as the velar stop k/q in Manchu and Written Mongolian as is consistent with the h- of Old Norse hreinn echoing the Cantonese and Hakka k- of Mandarin q in qilin.

Since the cervid terms got stuck on some ethnonyms, I suggest to Professor Mair to explore if the toponym Krorän or Kroraina (楼兰) for an archaic civilization site in Xinjiang could be explained in terms of Proto-Indo-European *kroinos.

Deven Patel said,

December 24, 2018 @ 7:32 pm

In Hindu lore, there is, of course, the very famous archetype of the unicorn Rishyashringa, literally, "the sage with the horn on his head," the product of a deer lapping up the urine of a powerful sage [sages, through seminal retention, have stored up much power to reproduce and whatever emission they release, even if lapped up orally, can produce a child]. This sage is then very much connected to reproductive fecundity and his seduction releases the rains in a nearby city beset by drought. Another instance I can recall is from Wasson's book on Soma, where he discusses the famous third filter of the legendary plant soma possibly being the urine of a sacred animal. He tied the potential importance of the horse or cow to the deer, whose urine, fortified by the hallucinogenic mushrooms they ingest, the herdsmen on the Central Asian steppes drink to get high.

Victor Mair said,

December 24, 2018 @ 9:52 pm

From Diana Zhang:

Speaking of the cervid versus equid radicals of 麒麟/騏驎, it reminds me of the Old Sinitic forms of 馬 and 鹿 — Baxter and Sagart (2014) reconstructs 馬 as *mˤraʔ and 鹿 as *mə-rˤok, and Schuessler (2007 and 2009) reconstructs them as *mrâʔ and *rôk. Both are type A sounds. In Sino-Tibetan languages the ml- initial also seems to connect these two animals, for example, "horse" in Burmese is mrang, based on which Yakhontov (1960) reconstructs its proto-form as *mla. Further, according to the 淮南子, the ancestor of 麒麟 is 毛犢 *mˤaw·lˤok (type A sounds for both syllables in 毛犢 too, which means that they share the same phonological derivational processes with those of 馬 and 鹿). …. I'm wondering to what extent such a phonetic connection between horses and deers in the Old Sinitic may substantiate the imagery of antlered horses in ancient China. This post is so inspiring!

Victor Mair said,

December 24, 2018 @ 10:07 pm

Diana Zhang's excellent comment reminded me of a famous set phrase from history: "pointing at a deer and calling it a horse". The story behind it is told in this article:

=====

The Chinese idiom “point to a deer and call it a horse” (指鹿為馬, pronounced zhĭ lù wéi mă) refers to confounding right and wrong, deliberately misrepresenting the truth, or distorting the facts for ulterior motives.

The idiom originated from the Qin Dynasty (秦朝) (221–206 B.C.) following the death of Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇), the first emperor of the dynasty and first emperor of a unified China after the state of Qin conquered all of the other states of that period.

During the reign of Qin Er Shi (秦二世), literally the “second emperor of the Qin Dynasty” in 210–207 B.C., the prime minister, Zhao Gao (趙高), was a man with greedy ambitions bent on usurping power.

He wished to rebel and take the throne but feared that some of the officials might be against him. Therefore, he devised a way to identify them as well as to determine his own influence in the court.

One day, he rode a deer on an outing with the emperor. The emperor asked, “Prime Minister, why are you riding a deer?”

Zhao Gao replied, “Your Majesty, this is a horse.”

The emperor said, “You are mistaken! That is clearly a deer!”

Zhao Gao responded, “If Your Majesty does not believe me, then we must ask the ministers for their opinion.”

When the ministers were asked, half told the truth and said it was a deer, while the other half, either fearing Zhao Gao or supporting him, said it was a horse.

Facing this situation, the emperor actually doubted himself and chose not to believe his own eyes but to believe the words of the treacherous minister.

Later generations used the idiom “point to a deer and call it a horse” to describe a situation in which someone reverses black and white and turns the truth upside down in order to deceive others.

=====

Steve said,

December 25, 2018 @ 10:07 am

Père David's deer is often credited with having equid characteristics…

Jichang Lulu said,

December 25, 2018 @ 10:14 am

Magnus Fiskesjö recently used the ‘point at a deer and call it a horse’ simile to refer to the media tactics of the notorious PRC ambassador to Sweden, His Perestroika-Panicked Excellency Gui Congyou 桂从友 Гуй Цунъю, one of the protagonists of the ‘This is killing’ Stockholm porcelain-bumping incident. Serendipitously to a post on Old Sinitic etymology, Fiskesjö used to be the director of the Stockholm Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities (Östasiatiska museet), a post once occupied by a pioneer of the field, Bernhard Karlgren.

The simile puts the ambassador in the role of minister Zhao Gao 赵高. His zeal in carrying out extraterritorial media ‘guidance’, slandering a kidnapped Swedish editor and implementing tantrum diplomacy arguably makes him worthy of the surname Zhao.

The locus classicus for the equino-cervine adage is here in the Records of the Grand Historian.

Chris Button said,

December 25, 2018 @ 1:03 pm

@ Diana Zhang

That’s a great observation, but unfortunately they are most likely unrelated. Baxter & Sagart’s *mə- in front of 鹿 is rightly critiqued by Schuessler in his review of their work for being based on a single form in an “obscure dialect” which could have deviated in a variety of ways. On the other hand, the *m- of 馬 is its root initial like the *r- of 鹿. Separately, Yakhontov’s *-l- in 馬 has been superseded by *-r- now resulting in the *mr- cluster in Schuessler's and B&S's reconstructions (by the way, Inscriptional Burmese which, unlike Written Burmese, could support *ml- clusters only shows evidence for *mr-).

Chris Button said,

December 25, 2018 @ 1:22 pm

I might add that I've always like Sagart's (1999) proposal that 角 and 鹿 are related such that 鹿 can be etymologized as the "horned one" much like "cervid" in Indo-European.

martin schwartz said,

December 25, 2018 @ 3:44 pm

Briefly: For the Indo-European etymon in question, see in depth

A. Nussbaum, Head and Horn in Indo-European, 1986, which it appears Don Ringe reviewed in JAOS 1988. Two relevant take-aways is that the PIE initial is the palatal *k', , and not the velar *k,

and that from the basic etymon addition of the formant *-u/w- (among others) gives words for 'horn', e.g. Avestan srû-

(and 'horned animal', esp. cervids, like Lat. cervus, Welsh carw,

PGmc. *heru-ta-z 'hart', and forms in Balto-Slavic). For Uralic borrowing, cf. Saami çuarvi (my ç =c-hacek), Finnish sarvi 'horn'.

For 'deer', Iranian has *gavazna- (v = Eng. w) reflected in Av.,

Sogd., Khwar. , and MPers. (etc.) perhaps , *'noble/nondomesticated bovine', about which I can say more, and *âsûkâ 'gazelle' < 'swift', in many Ir. langs. No reindeers here. Re Victor Mair's broader remarks: Zoroastrianism should not be called Persian; it originated

in Central Asia (the homeland of the Iranian peoples), and entered

Persia as a syncretic package probably only within the Achæmenid

rule during Artaxerxid period, although worship of Ahuramazdâ is

earlier for the Achæmenians (a long story:I'll spare us the details).

Please note that "Persian" and "Iranian" are not synonymous for Iranists; the historical range of Iranian peoples and languages is vast, with Persia(n) in the west a late phenomenon, comparatively speaking. And we should speak of the Aryan sun-god Mithra;

there was an Indo-Iranian social divinity Mitra presiding over agreements, maintained bigtime in Iran in that function as Mithra,

who, in crossing the sky WITH the sun (Xvar) eventually became

a sun-god. We don't need Zoroastrian dualism for the symbolism of conflict seen in Rudenko's Scythian animal scenes; btw the Scyths spoke an Iranian language, but no evidence in Pazyryk for their being Zoroastrians.

David Marjanović said,

December 25, 2018 @ 3:50 pm

Awesome! In either reconstruction, these two sound similar enough to explain where 指鹿為馬 comes from.

I'm sorry if I come across as a grumpy naysayer. Nothing about the "*kroinos" story is flat-out impossible. I merely mean to point out that the evidence, to the extent that we have any, weighs against it more heavily than it may seem.

Yes, Old Norse was spoken next to boreal forest with reindeer in it, and so was Proto-Germanic most likely, so it's possible that the ON word is inherited straight from PGmc; and I don't know how far north the Pit Grave (yamnaya) culture or its immediate predecessors (Khvalynsk…) or successors reached, so I, for one, can't exclude inheritance straight from (nuclear) PIE on semantic grounds. I'm just saying that this is a pretty long chain of inference.

Fair enough. What would the extension mean, and is there evidence for its existence?

I'm not talking about dimidiation* here, but about the idea – which goes back very far in China, as you know better than I do – that every character/syllable must have a meaning, so that seemingly disyllabic morphemes must be compounds. The "butterfly" word, too, was long explained as "male butterfly + female butterfly", and I think it has its own LL thread somewhere.

* Why not just call it epenthesis?

BTW, that (Hydropotes inermis) s a fascinating animal: instead of antlers (inermis = "unarmed"), it has very, very long upper canine teeth that stick far out of its mouth.

==============================

Why do you think they are? I'm not saying it's impossible, just asking why you say they are without further comment.

This part seems fair enough…

Why would this happen? Manchu doesn't have a problem with /rd/, does it?

Antelope including gazelles are not deer. They have real horns, not antlers. They're closer to cattle, buffaloes, sheep & goats than to deer.

This part is flat-out impossible.

1) Geography.

2) Why would eo – which was just what it looks like: [ɛɔ̯] or thereabouts – be represented by [ɑ]? Why not by [ə] or [i] or [o], which Middle Mongolian also had to offer?

3) Why would [h] be represented by [qʰ], instead of simply by [h], which Middle Mongolian also had to offer? In most of today's Mongolic languages, this [h] has disappeared, and [qʰ] has become [χ] or even [h], but that was not yet the case in the times of Genghis Khan, who was not a [χɑːn] yet, but a [ˈqʰɑɦɑn].

And if we take your proposal less literally, so as to lessen the severity of 1) and 2), fresh new problems arise. The Proto-West-Germanic ancestor of heort was *herut, which looks even less like *qarta-. You can still see this from the fact that Old English eo comes from *e…u. In High German, BTW, this same sequence first became i…u, which is indeed found in the Old High German form hiruz (where z stands for /s/, the regular outcome of word-final */t/ after a vowel). Later in the history of German, the u dropped out as usual, and /rs/ became /rʃ/ by another regular change, giving the modern form Hirsch.

I strongly recommend that you discuss your proposal with experts in at least one of the language families involved before you try to publish it.

Victor Mair said,

December 25, 2018 @ 7:54 pm

Essential reading for those who are unfamiliar with the concept of disyllabic morphemes like húdié 蝴蝶 ("butterfly") in Old Sinitic. This disyllabic word was the subject of a famous article by the Yale linguist, George A. Kennedy, titled "The Butterfly Case" (in Wennti, 8 [March, 1955]), which was a followup to his even more famous piece called "The Monosyllabic Myth" (in Journal of the American Oriental Society, 71.3 [1951], 161-166), both of which are reprinted in Tien-yi Li, ed., Selected Works of George A. Kennedy (New Haven: Far Eastern Publications, 1964), respectively pp. 274-322 and pp. 104-118. In these articles, Kennedy was writing about the fact that some Sinitic morphemes are disyllabic and how húdié 蝴蝶 ("butterfly") is a prime example. The case is recounted in brief in J. Marshall Unger's Ideogram: Chinese Characters and the Myth of Disembodied Meaning (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004), p. 7.

See also "'Butterfly' words as a source of etymological confusion" (1/28/13) for a detailed discussion of the etymology of húdié 蝴蝶 ("butterfly").

Victor Mair said,

December 25, 2018 @ 9:20 pm

From Sunny Jhutti:

Interesting that the Punjabi word for deer is hrein.

MARTIN SCHWARTZ said,

December 26, 2018 @ 2:02 am

The word cited as Punjabi hrein looks suspiciously like Hindi hiraNi

vel sim. etc. 'deer' < Skt. hiranNya- 'golden, tawny'.

Such coincidences are many, and cease to be interesting after a while. Eng. bad and Pers. bad /bæd/ are rejected as cognates because of their historical phonic (and semantic) irreconcilability;

Pers. se, Azari vestigial Iranian hara, and modern Indo-Aryan tîn vel sim. '3' are regular cognates in view of their Indo-Iranian history. Ya gotta know the RULES.

Sean Manning said,

December 26, 2018 @ 5:09 am

Martin Schwartz: yes, it is usually said that the Saka and Gimmeraya and Skythes must have spoken Iranian languages, but as far as I know most of the evidence is circumstantial ("they lived at a place and time and in a way which fits our reconstruction of Indo-European speakers") rather than linguistic. There was that interesting article by Adrienne Mayor and a Caucasian philologist a few years ago.

As far as I know, the sum total of evidence for languages on the Eurasian steppes in the middle of the first millennium BCE is names transcribed in Greek and Babylonian, and I have not seen a systematic study of them.

Chau said,

December 26, 2018 @ 7:56 pm

@ Penglin Wang

You clearly stated that what you posted in the LL Comments was just an abstract of your poster presentation in a recent conference. By the very nature of abstract, a lot of details have to be left out. It was not fair for you to be criticized with points that were beyond the scope of a mere abstract. Do not feel discouraged by such kind of criticism.

Geography should not be an impediment to the historic spread of languages. Otherwise, we would be hard put to explain the wide distribution of Austronesian languages, which, once having branched out of Taiwan, spread far and wide, from Madagascar in the West to Easter Island in the East. Neither can we explain why Tocharian, a centum subgroup of the IE family, is found east of the satem IE languages and right next door to Sinitic. People migrate, that's why.

Anthropology should provide us good insight into historical linguistics. After all, language spread relies on the "word of mouth". We need researchers like you to study the migration of Western languages into Asia because you ask questions from your unique anthropological perspectives. As Jacob Bronowski says in his book, "The Ascent of Man" (1973, p. 153), "That is the essence of science: ask an impertinent question, and you are on the way to the pertinent answer."

Chris Button said,

December 26, 2018 @ 11:17 pm

Regardless of the rhymes, I'm certainly not buying it until someone shows me some good evidence for a *mə- presyllable on 鹿. Furthermore, the story itself does not indicate that there is any such association to be made between the two animals. It would be like suggesting that the parable about "The Ass in the Lion's Skin" actually came about because "ass" and "lion" once sounded similar (and no I'm not suggesting that they did :) ).

I know – my (probably unnecessary) point was that there is also a long academic tradition of not doing so.

Because dimidiation entails epenthesis, but epenthesis does not necessarily entail dimidiation.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 27, 2018 @ 12:32 am

Boodberg's (1937) discussion of "dimidiation" is valuable but the concept is not clearly enough defined for use in modern discussions. His general idea was that at early periods, syllables with complex onsets were at times represented in writing with two Chinese characters. This certainly applies (down to the present) to cluster-onset words borrowed into cluster-impoverished languages like (Han and later) Chinese — of special interest are Boodberg's examples of possible early intra-Sinitic "borrowings"; this post addresses a hypothetical borrowing of a foreign cluster. But his idea looks less useful as an explanation of early Chinese rhyming binomes in general, where there are better ways of understanding the relevant terms. And none of the above involves epenthesis in the usual sense of phonetic-level or diachronic insertions.

Chris Button said,

December 27, 2018 @ 6:54 am

Again – my point wasn't to talk about dimidiation specifically here, but just to make a general point about scholarship. Having said that, what is relevant here is Jingtao Sun's work on "reduplication". However, as he himself points out (based on a comment by Pulleyblank) regarding the famous case of 蝴蝶, the 蝶 may well be related to 枼 instead of his reduplicated form from 挾. In the specific case of 蝶 (not necessarily making any comment on the rest of Sun's work), based on comparative evidence I suppose I tend toward the proposal that 蝶 was the root in the same way as 麟 here with the first character simply representing a pre-syllable of sorts. It is certainly no coincidence that both 蝶 and 麟 originally had liquid onsets, but the voiced onset of 蝴 does give me pause in that regard since that fits Sun's 挾 better. None of this is a topic I have ever studied too closely though.

David Marjanović said,

December 27, 2018 @ 7:24 am

That article, however:

1) did not at all question that most people called "Scythians" by the Greeks spoke Iranian languages. It merely said, quite plausibly, that "Scythian" was a term for anyone who lived in that general direction and perhaps had certain cultural features, and that could well have included speakers of West Caucasian languages.

2) is contradicted at length and in detail by this more recent paper, of which I post the abstract:

"A large number of Ancient Greek vases dated to the 1st millennium BC contain short inscriptions. Normally, these represent names of craftsmen or names and descriptions of the depicted characters and objects. The majority of inscriptions are understandable in Ancient Greek, but there is a substantial number of abracadabra words whose meaning and morphological structure remain vague. Recently an interdisciplinary team (Mayor et alii 2014) came up with the idea that some of the nonsense inscriptions associated with Amazons and Scythians are actually written in ancient Abkhaz-Adyghe languages. The idea is promising since in the first half of the 1st millennium BC the Greeks initiated the process of active expansion in the Black Sea region, so it is natural to suppose that contacts with autochthonous peoples might be reflected in Greek art. Unfortunately, detailed examination suggests that the proposed Abkhaz-Adyghe decipherment is semantically and morphologically ad hoc, containing a number of inaccuracies and errors of various kinds. The methodological and factual flaws are so substantial that it makes Mayor et alii’s results improbable."

By the very nature of an abstract, an abstract should not be presented as evidence on its own, without citations/links to further information, unless a publication is forthcoming soon. Is it?

Of course it's not that simple. There are no obstacles on the sea, so once the technology to sail beyond the horizon was available, nothing could stop the Austronesian languages from spreading across two oceans, it was just a matter of time. There are few obstacles on the steppe, so once wheeled vehicles and animals to pull them were available, nothing could stop Tocharian from spreading east all the way to the Altai mountains. The later spread south from there seems to have been much slower.

The fact that Tocharian has undergone the centum merger means very little. The centum merger happened more than once (and so did the satəm merger, which is also present in Tocharian in a slightly incomplete form). Other than the centum merger, Tocharian has nothing special in common with Germanic, Italic, Celtic, Greek or Hittite. Instead, there's evidence that all surviving IE languages are more closely related to each other than to Tocharian (which, in turn, is closer than the Anatolian languages such as Hittite were). For instance, most IE branches have lots of verbs with an extra vowel between the root and the ending ("thematic verbs"); Anatolian has none, which is part of the reason why the thematic verbs are thought to have arisen as reinterpretations of old so-called subjunctives (apparently originally a prospective verb form meaning more or less "is about to"); Tocharian has very few. Or take the verb root *yebʰ-, which simply meant "enter" in Tocharian, but became a euphemism for sexual intercourse in its sister branch, showing up with fertility-related meanings in Greek and finally as a coarse swearword in the "core satəm" languages (Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranian… with an interesting ritual use in the Rgveda).

Putting the genetic, archeological and linguistic evidence together suggests that all IE branches with living members come from the language spoken in the Pit Grave culture. That culture and the coeval Afanasievo culture have a common ancestor in the Khvalynsk culture. The Afanasievo culture was east of the Pit Grave culture, so the now usual scenario – that Afanasievo is where Tocharian comes from – bears out.

Assume an answer to your question, however, and you are on the way to a wrong answer.

Chris Button said,

December 27, 2018 @ 7:54 am

@ Jonathan Smith

I see now my earlier comment for comment replying to David Marjanović was ambiguous due to the lack of context. What I meant by "a long academic tradition of not doing so" was not that people should be talking about dimidiation more, but rather that people have been proposing alternatives (like dimidiation) to the notion that each individual character in a word should always have its own specific meaning for a long time.

Chau said,

December 27, 2018 @ 8:42 am

"for you to be criticized" should be read "to you to be criticized". Sorry about the error.

@ David Marjanović

I agree with you that there is danger of assuming an answer to a question a priori. However, the chapter in Bronowski’s book from which the quotation is taken talks about the role serendipity plays in the advancement of science, such as the discovery of penicillin. No assumption of anything is involved. It’s just that sometimes science is driven by curiosity.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 27, 2018 @ 12:11 pm

@Chris Button

Ah makes sense now and that is true…

re: David Marjanović "the verb root *yebʰ-, which simply meant "enter" in Tocharian, but became a euphemism for sexual intercourse in its sister branch"

The verb /jɐp D2/ simply means 'enter' (I think?) in Cantonese but became a euphemism for sexual intercourse in northern Chinese and hence a swearword (Mand. rì) coarse enough that 'enter' shifted vowel quality due to taboo pressure (> rù). This certainly seems a striking and impertinent enough connection to justify the selective disregard for (here early Chinese) evidence that would allow it to stand.

martin schwartz said,

December 27, 2018 @ 5:36 pm

Sean Manning: There is a V A S T body of linguistic evidence for

Saka languages. The Khotan(ese) Saka corpus alone is h u g e,, with a gigantic vocabulary, much studied by very competentIranists.

For Scythian, see the Encyclopaedia Iranica online article "Scythian language". Apart from the articles on Saka langs. in Enc. Ir., you can look at its "East Iranian languages". And Saka etc. in Wiki.

Sunny Jhutta: I asked a native speaker of Punjabi for his word for 'deer'; he knew nothing like your "hrein" and gave the form as hiran, without my prompting him. This is as I expected (above).

martin schwartz said,

December 27, 2018 @ 8:14 pm

Sean Manning: Gimmeraya? Gimme a break.

While I've often written about matters Saka, I know nothing about the language of the Cimmerians. or Gimri, or Gomer, or the like.

martin schwartz said,

December 27, 2018 @ 9:22 pm

Greek sources speak of a critter among Scythians, tarandos, about which I have no idea, but some think is a reindeer.

To be clear, I don't know what the Cimmerians spoke.

As for Mayor-Colarusso, I agree with the review David M. supplies;

I refused to wasrte time refereeing it, once I saw examples of their thesis.

Chris Button said,

December 28, 2018 @ 5:19 am

@ David Marjanović

Way out of my depth, but in anticipation of a response from Penglin Wang, I figured I'd ask a few questions of my own to your comments…

Yes. At least that's the way it looks in the written sources, doesn't it?

Presumably the desire is to somehow bring the Germanic coronal animal suffix into the equation? Not knowing the particulars of the possible loan process, surely it is this that then throws up the geographical question more than anything else? Otherwise, reflexes elsewhere can be applied.

Could you please specify your understanding of how the sounds in Middle Mongolian functioned from the velum and behind?

Sean Manning said,

December 28, 2018 @ 5:43 am

martin schwartz: the problem, of course, is that the Babylonians used Gimmeraya as their generic term for the peoples of the Eurasian steppes, like Greeks said Σκύθης and Persians saka-. Assuming that all of these exonyms referred to peoples speaking the same language family is dangerous, which is why I would like to see a study of all the onomastic evidence similar to Walther Hintz' and Jan Tavernier's work on the Iranian languages of the Zagros. Thanks for the citation to Rüdiger Schmitt's article.

It sounds like it would be helpful to search the vocabularies of the eastern Iranian languages for anything which might refer to reindeer. If that word is plausibly related to the Old English/Old Norse one, that would make Victor Mair's theory more likely.

Chris Button said,

December 28, 2018 @ 10:00 am

@ Victor Mair

Schuessler associates 廌 (~豸) *dràjʔ (or *dreʔ in his reconstruction) with Mon-Khmer *draay glossed in Shorto's dictionary as "kind of deer". Were you thinking along similar lines? The character 廌 itself is well-attested in the oracle-bones as some kind of hunted animal.

getintopc said,

December 28, 2018 @ 5:06 pm

Schuessler associates 廌 (~豸) *dràjʔ (or *dreʔ in his reconstruction) with Mon-Khmer *draay glossed in Shorto's dictionary as "kind of deer". Were you thinking along similar lines? The character 廌 itself is we

David Marjanović said,

December 29, 2018 @ 6:58 pm

I'm not sure what you mean. Do you mean that the Cantonese verb sounds eerily similar to the Sanskrit verb root (in particular)? The Middle Sinitic one didn't: the correspondence Cantonese /j/ ~ Mandarin r comes from the Middle Sinitic palatal nasal /ɲ/. I bet the Japanese kan'on pronunciation has a /n/.

I'm not sure what you mean. The claim is a loan into Mongolic from Old English; geography aside, that would mean we should expect different vowels and consonants than what the Middle Mongolian form has.

I'm not aware of having any unusual ideas here…? Given that intervocalic *g in "back"-vowel words (actually +RTR) and intervocalic *p are both ɣ in Written and ' in Middle Mongolian (qaɣan, qa'an), and were written with the same 'Phags-pa letter as an Early Mandarin sound that may have been [ɣ] or [ɦ], I'm postulating [ɦ] as the phonetic value; it's possible that that hasn't been done explicitly before, but it's hardly earth-shaking.

David Marjanović said,

December 29, 2018 @ 7:01 pm

Absolutely.

Chris Button said,

December 30, 2018 @ 6:15 am

@ David Marjanović

Middle Mongolian onsets: Are uvulars allophonic rather than phonemic? How does /h/ surface?

Manchu Codas: Isn't /n/ the only general option?

PIE *kʲr- + Germanic *-ut(a)-: Not being familiar with the "rules" here (to borrow Martin Schwarz's comment above), what jumps out at me more than anything is the desire to somehow incorporate the Germanic coronal component.

David Marjanović said,

December 30, 2018 @ 2:59 pm

Why would that matter for whether heort could be borrowed with a plosive?

Word-initially? No idea if it was [h] or [ɦ], though I think [ɦ] disappears more easily.

Chris Button said,

December 30, 2018 @ 5:57 pm

@ David Marjanović

Because these are suggestions of loans and (even if the proposals are completely misled, geography notwithstanding, as they may well be in this case) it is important to think beyond phonemes to look more closely at surface phonetics which can give results quite different from what you might expect just by trying to match up phonological segments. It is actually also important to do so in terms of internal reconstruction, although it is easier to get away without doing so (one of my pet-peeves with Old Chinese is how rigid algebraic formulae are often presented as a supposed linguistic reality).

Chris Button said,

December 30, 2018 @ 9:49 pm

To give a hypothetical example (that may or may not be relevant here), imagine a language with a velar phoneme /kʰ/ that has a uvular allophone /qʰ/ before low back vowels that tends to surface as a uvular fricative [χ]. In addition, it also has a phoneme /h/ that tends to surface as a voiced fricative of some kind (you suggest [ɦ] for Middle Mongolian above although presumably that does not necessarily imply any actual frication). Now, imagine a donor language with a phoneme /h/ that surfaces as a voiceless fricative of some kind. If we look simply at the phonemes, one might imagine that /h/ would pattern with /h/, but if we look at the phonetic reality, the voiceless frication associated with the phoneme /qʰ/ (~ /kʰ/) may well be preferable.

maidhc said,

December 31, 2018 @ 3:21 am

Deven Patel: The hallucinogenic chemicals in the mushroom amanita muscaria, which is used in Siberia, is passed through urine. People drink the urine of reindeer which have consumed the mushroom, or even of people that have consumed the mushroom. If you can't afford to buy the mushroom itself, maybe you can afford to buy the urine of the people who have consumed the mushroom. I think you can run it through about three digestive systems before it loses potency. There has been some speculation about whether this is what is meant for Soma in the Hindu scriptures.

The counterargument is that Siberia is a long way away from anywhere that the Hindu progenitors might have lived. And there are other possibilities for what Soma might be.

On a seasonal note, the colours of amanita muscaria (red and white) are much like the colours of Santa Claus, and it has been suggested that the whole Santa Claus thing (going back to Odin, probably) is connected to hallucinogenic mushrooms. And of course reindeer again.

David Marjanović said,

December 31, 2018 @ 6:58 pm

I agree completely; that's part of the reason why I tried to use phonetic rather than phonemic transcription – brackets instead of slashes.

Ah, so you think q may already have been [χ] (in some or all environments), as it is today (in all environments) at least in Buryat, Khalkha and Chakhar off the top of my head? I don't know if there's evidence for or against that.

However:

Suppose the donor language has [h], and the recipient language has [χ] and [ɦ] to offer. In that case, I bet [ɦ] would be used: the voice discrepancy is much less salient than the difference in friction + length + place of articulation. It takes people some practice to notice that the English/German h and the Czech/Slovak h are not identical.

David Marjanović said,

December 31, 2018 @ 7:05 pm

Did Father Christmas have any red on him before he was employed by Coca Cola? And I've never heard of reindeer associated with the French or the northern German versions. (The southern German version is, literally, "the Christ-child" – a preteen Jesus as a girlish angelic figure.)

Soma ( = haoma in the Zoroastrian scriptures) is repeatedly stated to be "pressed", so not likely to involve any urine.

BTW, Amanita is a genus name and therefore starts with a capital letter.

Victor Mair said,

January 1, 2019 @ 5:40 pm

From Doug Adams:

Let me list a few comments/observations about the (West) Germanic linguistic data.

1. OE hrān is of course the expected equivalent of ON hrein. That it is the creation of some OE-ON bilingual of a 1,000 or so years ago seems to me highly improbable. Such a creation would be well within the realm of possibility of a 19th century philologist, but I can think of no analogous behavior anywhere in the time period when hrān appears.

2. One must remember that the ancestral Anglo-Saxon homeland was in Slesvig and adjacent Jutland. There may have been reindeer there in the early centuries AD. Caesar mentions what must be reindeer in De Bello Gallico as inhabiting the Hercynian Forest in the first century BC. Obviously their southern limit of residence had steadily retreated northward in the first centuries AD but may not have retreated all the way to Scandinavia (still to be found n the forests of southern Norway) by the time of the Anglo-Saxon migrations.

3. At the time of those migrations, and for a few centuries thereafter, reindeer were still native in northern Britain (and Ireland?).

4. Meanwhile, on the continent, the Weser-Germanen and Elbe-Germanen had migrated south to areas no longer inhabited by reindeer and thus, not surprisingly, apparently had no word for them.

5. There is no word for reindeer in Gothic, but our Gothic linguistic data is (almost) entirely in the form of Bible translation and Wulfila, even if he were familiar with a word, would have had no cause to use it in the Bible.

6. There is no bar then to supposing that *hraina– was a Proto-Germanic word for reindeer. If, as generally supposed, Proto-Germanic was spoken in southern Scandinavia, and the shores of the Baltic and North Sea (Mecklenburg, Niedersachsen, etc.), it would have needed a word for an animal quite common in the environment.

7. I agree that there are no known extra-Germanic cognates.

Victor Mair said,

January 1, 2019 @ 6:41 pm

From Sasha Lubotsky:

Although I do not understand exactly what David Marjanović means when he is talking about the "centum merger" and "satem merger" in Tocharian, he seems to express a rather broadly shared opinion among the Indo-Europeanists that the Anatolian branch split off first, followed by Tocharian. It is more doubtful that the Pit Grave culture and the Afanasievo one are two independent continuations of the Khvalynsk culture, but this is not sheer nonsense and can be discussed. Michael Peyrot's two big projects are about these issues, so we'll know more within a couple of years.

Victor Mair said,

January 1, 2019 @ 6:51 pm

From Georges-Jean Pinault:

David Marjanović's statement about the isolation of Tocharian from the whole IE family is not correct. Most facts of morphology and lexicon show that Tocharian has several features in common with the other IE languages, it is not a "special" IE language, in any case much less special than Anatolian. Recent researches have shown that Tocharian is a much evolved IE language, which developed more or less from the same state as all other IE languages, except Anatolian. See for instance papers by Melanie Malzahn, and one that appeared in the proceedings of the 14th Fachtagung der Idg. Gesellschaft, also the book by Thierry Zarcone (anthropologist in CNRS, France): Le Cerf. Une symbolique chrétienne et musulmane, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2017.

Victor Mair said,

January 2, 2019 @ 12:19 am

From Michael Weiss:

The text you quote from David Marjanović presents what I take to be the, or a, standard view these days. Tocharian is widely regarded as the 2nd to branch off of PIE after P-Anatolian. Note, for example, that Tocharian like the rest of IE, except Anatolian, has a fully developed feminine gender and morphological traces of the active (*-nt) and middle participles (*-mh1no-) more or less in functions derivable from their Classical IE uses unlike Anatolian where the *-nt participle is passive to transitive roots. It's true that Tocharian has few simple thematic verbs (though I wouldn't endorse any particular view of the origin of the thematic paradigm. It's also not quite true, btw, that Anatolian has no thematic verbs. It has HLuv. tammari 'builds' from *demh2eti at least, but it is the case that simple thematics are very rare.) The *Hyebh- case is probably a semantic archaism but Polish does use compounds of jebać as a verb of motion (according to Dariusz Piwowarczyk), so it's not conclusive. Another notable archaism is the Tocharian class 3 s-preterite which has an s only in the 3rd person like the preterite of the hi conjugation in Hittite. According to Jasanoff this is the original pattern for what became the s-aorist in Classical IE with an s throughout the entire paradigm. But not everyone follows this view. The existence of o-grade ~ zero-grade ablaut in paradigms (the so-called subj. V) which do not obviously continue the perfect may be another archaism. On the other hand, I should note that some Tocharianists (e.g. Pinault, Malzahn) are I think agnostic on this general question.

Victor Mair said,

January 2, 2019 @ 9:30 am

From Melanie Malzahn:

The question of the position of Tocharian among the other IE languages is actually not that straightforward. Even many linguists such as Jay Jasanoff from Harvard believe in what we call the "second split off" by Tocharian from the PIE community (after Anatolian but before the other IE languages).

I personally do not believe that, as I have said in my book (The Tocharian Verbal System. Leiden/Boston: Brill 2010) and in this kind of recent paper

“The second one to branch off? The Tocharian lexicon revisited”, Etymology and the European Lexicon. 14th Fachtagung of the Indogermanische Gesellschaft, 17 – 22 September 2012 in Copenhagen, ed. by Birgit Olsen et al., Wiesbaden: Reichert 2017, 281-292

Chris Button said,

January 3, 2019 @ 12:30 pm

@ David Marjanović

I don't know enough about the languages in question to make any comment in that regard. I'm just cautioning against making any outright rejection of proposed loans based on correspondences (or lack thereof) between phonemes. Take 虎 "tiger" which I would reconstruct in Old Chinese as *ʰráɣʔ (Schuessler has *hlâʔ). It is undoubtedly a very old loan from Mon-Khmer *klaʔ "tiger" that is attested in the earliest inscriptions. Now, Old Chinese actually had *kl- clusters as onsets, but that is no reason to reject the validity of the association on the basis that the OC form would have to have been *kláɣʔ (or some such thing) since the surface phonetics were what really mattered.