Persian peaches of immortality

« previous post | next post »

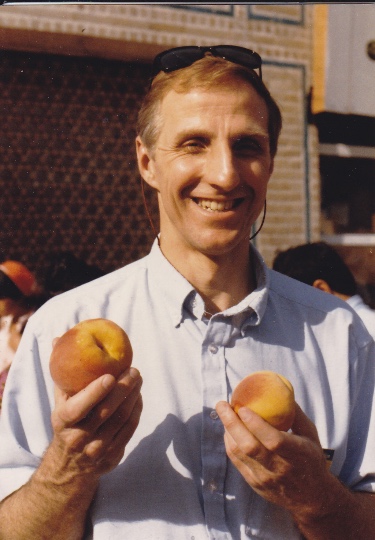

When I visited Samarkand about 35-40 years ago (before digital days), I ate some of these luscious, mythic peaches:

Worth reading:

Edward H. Schafer, The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'ang [618-907] Exotics (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1963).

See also Berthold Laufer, Sino-Iranica: Chinese Contributions to the History of Civilization in Ancient Iran, Publication 201, Anthropological Series, Vol. XV, No. 3 (Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1919), p. 379.

Another mythic peach that came to China from the west was like what we nowadays refer to as pántáo 蟠桃. This kind of peach is called by many names in English:

doughnut peach or donut peach, paraguayo peach, pan tao peach, saucer peach, flat peach, belly-up peach, UFO peach, Saturn peach, Chinese flat peach, hat peach, anjeer peach, custard peach, wild peach, white peach, pumpkin peach, squashed peach, bagel peach or pita peach

(source)

Also relevant:

The Queen Mother of the West, known by various local names, is a goddess in Chinese religion and mythology, also worshipped in neighbouring Asian countries, and attested from ancient times. The first historical information on her can be traced back to oracle bone inscriptions of the fifteenth century BC that record sacrifices to a "Western Mother". Even though these inscriptions illustrate that she predates organized Taoism, she is most often associated with Taoism. From her name alone some of her most important characteristics are revealed: she is royal, female, and is associated with the west. The growing popularity of the Queen Mother of the West, as well as the beliefs that she was the dispenser of prosperity, longevity, and eternal bliss took place during the second century BC when the northern and western parts of China were able to be better known because of the opening of the Silk Road.

…

The Queen Mother of the West usually is depicted holding court within her palace on the mythological Mount Kunlun, usually supposed to be in western China (a modern Mount Kunlun is named after this). Her palace is believed to be a perfect and complete paradise, where it was used as a meeting place for the deities and a cosmic pillar where communications between deities and humans were possible. At her palace she was surrounded by a female retinue of prominent goddesses and spiritual attendants. Although not definite there are many beliefs that her garden had a special orchard of longevity peaches which would ripen once every three thousand years, others believe though that her court on Mount Kunlun was nearby to the orchard of the Peaches of Immortality. No matter where the peaches were located, the Queen Mother of the West is widely known for serving peaches to her guests, which would then make them immortal. She normally wears a distinctive headdress with the Peaches of Immortality suspended from it.

(source; see also here and here)

In an exciting paper, Elfriede R. Knauer demonstrates a connection with the Anatolian mother goddess Cybele. See her "The Queen Mother of the West: A Study of the Influence of Western Prototypes on the Iconography of the Taoist Deity." In Victor H. Mair, ed., Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006), pp. 62–115.

The Queen Mother of the West and her peaches of immortality figure prominently in the 16th-century vernacular novel, Journey to the West, where the naughty Hanuman-like monkey, Sun Wukong, tries to steal some of them:

The Peaches of Immortality are a major item featured within the popular fantasy novel Journey to the West. The peaches are first encountered when, in heaven, Sun Wukong is stationed as the Protector of the Peaches. The peach garden include three types of peaches, all of which grant over 3,000 years of life if only one is consumed. The first type blooms every three thousand years; anyone who eats it will become immortal, and their body will become both light and strong. The second type blooms every six thousand years; anyone who eats it will be able to fly and enjoy eternal youth. The third type blooms every nine thousand years; anyone who eats it will become "eternal as heaven and earth, as long-lived as the sun and moon." As the Protector, Sun realizes the effects of the sacred peaches and acts quickly as to consume one, before he runs into trouble when Xi Wangmu arrives to hold a peach banquet for many members of Heaven. Sun Wukong makes himself very small to hide within a peach during the banquet, before consuming more, thus gaining immortality and the abilities that come with the peaches.

Later on, Sun Wukong has a second chance to eat a fruit of immortality. A 1,000-foot-tall (300 m) tree grows behind a monastery run by a Taoist master and his disciples, though the master is away. Once every 10,000 years, the tree bears 30 of the legendary Man-fruit, which just like newborn babies, complete with sense organs. The man-fruits grant 360 years of life to one who merely smells them and 47,000 years of life to one who consumes them. Fruits of immortality are not seen again after this point in the novel.

(source)

Persianate Central Asia was the fount of so many marvels whose origins are lost in the distant past: Heavenly Horses, religions and philosophies, swords, and so forth and so on. If they were not always the initial originators of so many important aspects of Eurasian culture (which in many cases they were indeed), they were the kulturvermittlers par excellence, as I am fond of saying of them.

Selected reading

- "Kids Bong" (11/10/18)

- "On not speaking Taiwanese" (12/2/18)

[Thanks to Robin Schaufler]

Stephen L said,

January 22, 2021 @ 2:47 pm

trivia: peach in Latin is Persicum (persicum pōmum – persian fruit), which in German ended up as "Pfirsich", which I always had trouble with, and I had to prove to myself that it was a weird word – my 'proof' being that it's the only word other than the (admittedly really common pronoun) "sich" that ends with "sich" [ My brain always wanted to say "Pfirisch", which it still holds to be a more convincing German word ].

Y said,

January 22, 2021 @ 2:59 pm

Well? How were the peaches?

Philip Taylor said,

January 22, 2021 @ 3:15 pm

I confess, with not inconsiderable embarrassment, that I have always thought that the German was "Pfirsch", presumably by analogy with "Kirsch". I am indebted to you, Stephen, for correcting this life-long misapprehension of mine.

Victor Mair said,

January 22, 2021 @ 3:25 pm

@Y:

Luscious, juicy, sweet, fragrant — the best peaches I've ever had in my life.

I will live a long time.

Victor Mair said,

January 22, 2021 @ 6:13 pm

I should mention that I am extremely allergic to peaches, as I am to nearly all other fresh fruits like cherries and apples, but mostly peaches, such that in the summer of 1973 [?] when I was teaching Mandarin at Harvard, I ended up writhing on the floor and had to be rushed to the hospital (my stomach felt as though it were being tightly tied in knots) after eating one.

Upon reading this post, my sister Heidi asked me if I had such an allergic reaction after eating the golden peaches of Samarkand. I told her that I washed them thoroughly and peeled off the skins.

It was worth the risk. They were divine. I did not go into convulsions.

alex said,

January 22, 2021 @ 7:18 pm

What a wonderful smile!

cameron said,

January 22, 2021 @ 7:29 pm

I'm going to have to remember "I did not go into convulsions" as a phrase to use when describing exotic foodstuffs

Chris Button said,

January 22, 2021 @ 7:45 pm

I don't think it's coincidental that there's something very motherly about the graphic forms and pronunciations of 梅 "apricot, plum" and 莓 "strawberry".

Victor Mair said,

January 22, 2021 @ 7:59 pm

And 梅 is my Chinese surname.

Méi Wéihéng 梅維恒

Nat J said,

January 23, 2021 @ 1:08 am

From now on, if the host of a dinner party doesn't offer me immortality-granting peaches, I'm going to be insulted, frankly.

David Marjanović said,

January 23, 2021 @ 10:08 am

That's the prefix form (e.g. Kirschwasser "some kind of cherry distillate"). The isolated singular is Kirsche, pl. Kirschen with silent e in the latter.

Philip Taylor said,

January 23, 2021 @ 10:51 am

Thank you David. My German is entirely learnt by ear, so my spelling can unfortunately be wildly inaccurate at times …

Calvin said,

January 23, 2021 @ 10:52 am

The mythic peach 蟠桃 is a symbol for longevity in the Chinese culture. It is one of the symbolic items held by the Shouxing (壽星) deity: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanxing_(deities).

This also extends to 壽包, buns made to resemble the peach shape with a dash of red coloring, served in birthday banquet/meal (e.g. https://chunwinglung.blogspot.com/2018/06/blog-post_3.html).

Slumbery said,

January 23, 2021 @ 12:39 pm

"trivia: peach in Latin is Persicum (persicum pōmum – persian fruit),"

The dictionaries I looked up say that it was used with malum instead of pomum, but it is perfectly possible that both forms were in use of course.

M. Paul Shore said,

January 23, 2021 @ 3:00 pm

Perusers of this thread might enjoy reading the 1913 poem "The Golden Journey to Samarkand" by the brilliant, doomed English poet James Elroy Flecker (1884-1915). (A trigger warning, though, for those who might be bothered by the poem's exuberant Orientalism, and/or by one of its characters uttering an offhand anti-Semitic remark.)

David C. said,

January 23, 2021 @ 3:39 pm

@Prof. Mair – thanks for sharing the picture. I wonder what persuaded you to take the risk of trying the golden peaches, knowing you may potentially have a severe reaction.

@Calvin – as the post in your second link describes, these buns served at banquets and birthday celebrations are traditionally called 壽桃 (longevity peaches). 壽包 (longevity buns) on the other hand are served after funerals or offered to ghosts during the Ghost Festival.

Philip Taylor said,

January 23, 2021 @ 3:44 pm

I did indeed enjoy reading it, Paul. Thank you for introducing me (and perhaps others) to it.

M. Paul Shore said,

January 23, 2021 @ 3:55 pm

Philip,

Unfortunately, for some reason the posting of the poem that you've linked to is missing a considerable amount of the poem's text. Here's an alternative posting, which I assume is complete (though I don't actually know that for certain): https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/golden-journey-samarkand

Philip Taylor said,

January 23, 2021 @ 4:28 pm

Ah, thank you Paul — I now see and appreciate what I would otherwise have missed.

Victor Mair said,

January 23, 2021 @ 7:51 pm

@David C.

When I was younger, I took a lot of crazy risks. A cat has 9 lives. After I had used up 8 of mine by around the age of 60, I have become a bit more cautious, but not much.

Anyway, knowing what I did about the deep myth and history of the golden peaches of Samarkand, there's no way I would pass up the rare chance to eat one when it was offered to me, right on its home territory, no less.

Calvin said,

January 23, 2021 @ 11:10 pm

@David C.

These days they are simply called 壽包 for birthday celebrations, and the blog was lamenting the nuances have been lost in modern times except for the few who knows.

That blog has link to a message board discussion with the couple clarifying articles (in Chinese) quoted: https://cyclub.happyhongkong.com/viewthread.php?tid=50030.

The category of that discussion? 冷知識 (Obscure Facts).

R. Fenwick said,

January 24, 2021 @ 7:45 am

For what it’s worth, the Persian word for ‘peach’ is šaftâlu, which arises from Middle Persian šiftālūg and literally means ‘milk plum’. (For the semantics of ‘milk → sweet’, compare Parthian šift ‘milk’ and the adjectival derivative in šiftag ‘sweet’, lit. ‘milky’.)

Chris Button said,

January 24, 2021 @ 8:17 am

@ R. Fenwick

I think the plum (梅) / peach connection seems quite natural. Regarding 梅 and mothers, I'm always struck by how the phonetic 每 "every, flourish" (composed of a reduced form of 來/麥 "wheat" on top and 母 "mother") chimes with Demeter, the goddess of fertility and harvest, in which "meter" is of course "mother".

R. Fenwick said,

January 24, 2021 @ 12:12 pm

@Chris Button: I think the plum (梅) / peach connection seems quite natural.

Oh, indeed. With the Persian form I was more taken with the semantic shift associating peaches with milk (though peaches and cream is certainly a wonderful combination!). Regarding the plum/peach link, in Circassian a similar link appears: the peach in Proto-Circassian is *pqː(ʷ)ə-ʦʰá "hairy plum", by way of contrasting it with *pqː(ʷ)ə-ɕʷ’əʦ’á, the "black plum", Prunus domestica subsp. domestica. (A third Proto-Circassian form is reconstructible, as well: *pqː(ʷ)əgʷəɬə is the cherry-plum P. cerasifera subsp. divaricata, which is the âluče of Persian and the basis of that wonderful Georgian sauce, ტყემალი t’q’emali. However, the semantics of the element *-gʷə̀ɬə in Proto-Circassian remain unclear; my best guess is that it might represent a dissimilation by loss of the labial element from an earlier *-gʷə-pɬə "red heart".)

cameron said,

January 24, 2021 @ 3:21 pm

While shaftālu is certainly a fine word for peach in Persian, the more common everyday term is holu (هلو), at least in the Tehrani dialect.

The word ālu, meaning plum is used in other fruit names as well. An apricot is a zardālu, a yellow plum. A persimmon is a khormālu, a date-plum.

Oddly a greengage, a very plum-like fruit indeed, isn't called a kind of plum, but is referred to as a goje (گوجه), or goje sabz, green goje. The English word greengage, is supposedly derived from the name of an English gardener called George Gage, who imported some trees from Turkey at some point. The similarity to the Persian word makes that origin story a bit suspicious

Philip Taylor said,

January 24, 2021 @ 3:54 pm

The OED differs only in personal name :

cameron said,

January 24, 2021 @ 5:16 pm

My memory must have mis-filed the eminent Mr. Gage's name, as "George" probably because "George Gage" has a ring to it . . .

R. Fenwick said,

January 24, 2021 @ 10:42 pm

@cameron: While shaftālu is certainly a fine word for peach in Persian, the more common everyday term is holu (هلو), at least in the Tehrani dialect.

You're right, of course – doing a bit more poking around, it appears that in modern Persian varieties, šaftâlu is typical of Dari but no longer in Tehrani. (In my defence, I didn't come across holu because I was only looking for a Persian phonetic equivalency of the Turkish term.)

Also, in view of Tajik шафтолу "peach" it would seem that Tehrani holu results from a rather recent shift in usage frequency, which is also consistent with Turkic: the Turkish term is quite old, attested all the way back to Old Oghuz şeftālu (Kipchak-Cuman also exhibits şeftālū, though already with a variant şeftāli), and it's probably at that much earlier point that the term was borrowed from Early Modern Persian. Only Azeri – which has maintained the closest contact with modern Tehrani Persian – has also borrowed the Tehrani form, as hulu "large variety of yellow peach".

A persimmon is a khormālu, a date-plum.

The link between persimmons and dates has always intrigued me. Neither the trees nor the fruits have a great deal in common with one another from a botanical or morphological point of view. Do you happen to know what the rationale is in this arena?

cameron said,

January 25, 2021 @ 12:18 am

With regard to the word khormālu, to refer to a kind of persimmon: I grew up calling them khormālu in Persian and persimmons in English, but it seems the fashion now is to call them date-plums in English. They are a completely different species from the North American persimmon. I suspect they're likened to dates simply because they're so sweet. Dates (and figs) are sweet like candy; a date-plum isn't quite that sweet, but is on the way there compared to plums, peaches, apricots, etc.