"Crisis = danger + opportunity" redux

« previous post | next post »

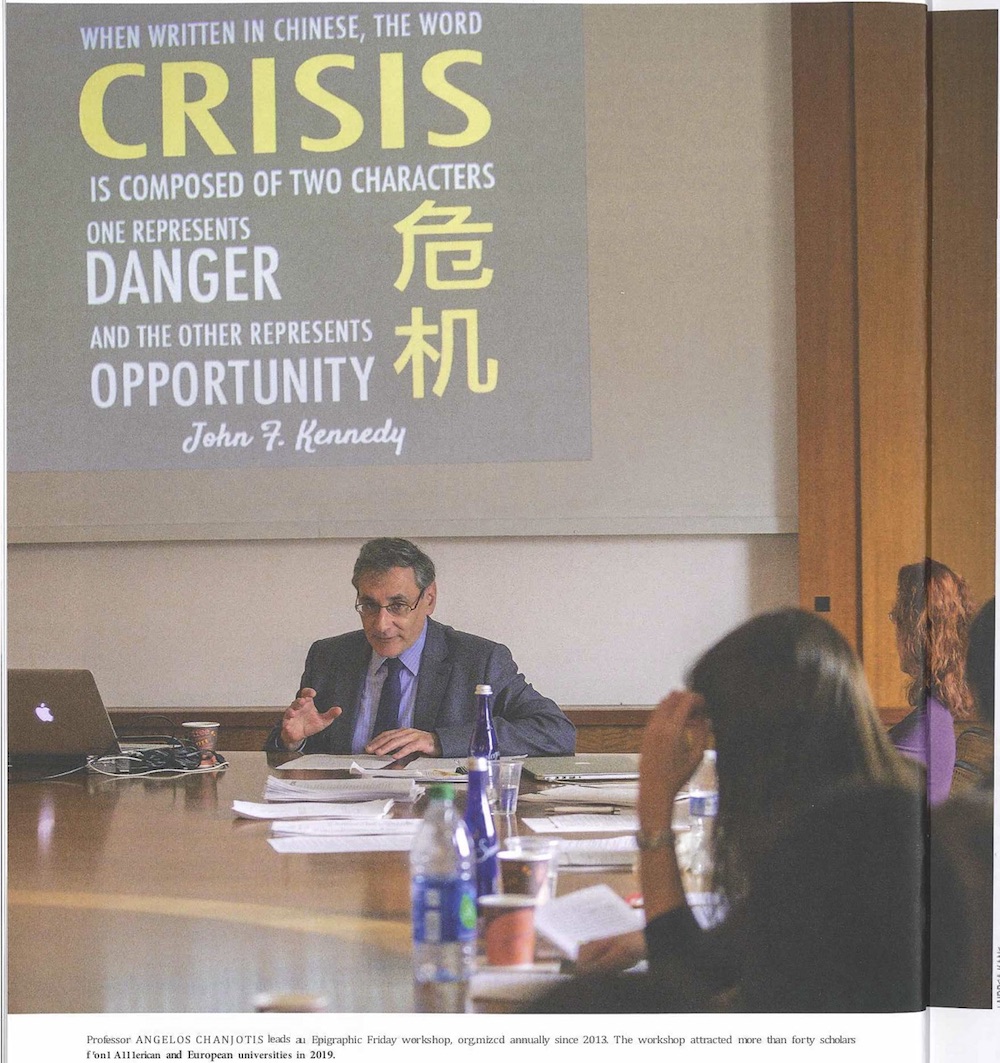

From IAS: Institute for Advanced Study; Report for the Academic Year 2018-2019, p. 8:

The scholar in the photograph is the Greek historian Angelos Chanjotis, who is shown leading an Epigraphic Friday workshop. I don't know what Professor Chanjotis may have said about the Chinese word for "crisis" on that occasion because I was not present, but I am dismayed that the false etymology of the term is being projected even in the hallowed precincts of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.

More than a decade ago, when it was circulating widely, I made a determined effort to debunk this tenacious trope with a long essay under the title "danger + opportunity ≠ crisis: How a misunderstanding about Chinese characters has led many astray" (Pinyin.info [2009]). Since its publication, that essay has been viewed countless times, and I have received many messages of gratitude for having written it, plus a few letters of anguish telling me that I have destroyed their comforting illusion. I, on the other hand, have been much solaced by the fact that I've barely encountered this pernicious meme during the past seven or eight years.

The reason for the resurfacing of the myth that the Chinese word for "crisis" means "danger" + "opportunity" at this particular juncture is tied to a genuine crisis of gigantic proportions that is going on in China right now, namely, the epidemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), formerly known as 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease and a swiftly shifting series of other names, including "Wuflu", which has as its epicenter the sprawling city of Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province. See also 2019–20 coronavirus outbreak and, for a recent discussion of "epi-", "On the center" (2/15/20).

Hoping to make the best of a grim situation, propagandists and pandits in the PRC are once again chanting the mesmerizing mantra: "Crisis = danger + opportunity".

Readings

- "Crisis ≠ Danger + Opportunity" (4/29/05)

- "Etymology as argument" (6/18/05)

- "Hollywood glamour, activist passion, false rhetoric" (4/24/06)

- "Rice v. Mair" (1/27/07)

- "Stop him before he tropes again" (3/22/07)

- "Crisis = danger + opportunity: The plot thickens" (3/27/07)

- "Trope-watch, Oslo edition" (12/11/07)

- "The crisis-(danger)-opportunity trope, de-Sinicized" (3/7/09)

- "Chinese word for 'crisis'" (Wikipedia)

- "danger + opportunity ≠ crisis: How a misunderstanding about Chinese characters has led many astray" (Pinyin.info [2009])

[Thanks to Linda Greene]

Philip Taylor said,

February 19, 2020 @ 4:39 pm

"propagandists and pandits in the PRC" — is "pandits" the normal spelling in <Am.E> for such people ? Here in the UK we know them as "pundits", reserving "pandit" for only the truly eminent (e.g., Pandit Nehru).

Ben Zimmer said,

February 19, 2020 @ 4:52 pm

Even if they're propagating a debunked bit of language lore, at least the Institute for Advanced Study properly quoted Kennedy, albeit with slightly modified wording. There were at least three iterations of the JFK quote, and the IAS version most closely matches the first one:

"When written in Chinese, the word 'crisis' is composed of two characters — one represents danger and one represents opportunity." (Convocation of the United Negro College Fund, Indianapolis, Apr. 12, 1959)

"In the Chinese language, the word 'crisis' is composed of two characters — one representing danger, and one representing opportunity." (United States-India Conference, Washington DC, May 4, 1959; same wording used at the University of New Hampshire, Mar. 7, 1960)

"In the Chinese language, the word 'crisis' is composed of two characters, one representing danger and the other, opportunity." (Valley Forge Country Club, Oct. 29, 1960)

I discussed the JFK quote, as well as its precursors, in the posts from 3/22/07 and 3/27/07 linked by Victor above.

y said,

February 19, 2020 @ 8:05 pm

Now, a word 拐点 is used in the Coronavirus crisis to mean the "turning point." It seems to be originally an English term, "inflection point," used in mathematics.

Michèle Sharik Pituley said,

February 19, 2020 @ 8:14 pm

@Philip Taylor: I have never heard an American say "pandit", nor have I ever seen it in print prior to today. Only "pundit".

Victor Mair said,

February 19, 2020 @ 10:50 pm

pundit About 29,700,000 results

pandit About 66,600,000 results

Peter Grubtal said,

February 20, 2020 @ 12:48 am

Yes, this meme of crisis in Chinese = opportunity was doing the rounds in management seminars 15 or more years ago.

It was a nice one for the consultants, added a bit of intellectual veneer to their presentations, which otherwise were pretty short on substance.

Mark S. said,

February 20, 2020 @ 3:31 am

Although the most recent minor amendments to "danger + opportunity ≠ crisis: How a misunderstanding about Chinese characters has led many astray" date from September 2009, it's perhaps worth noting that the essay was originally posted in December 2004.

Michael Watts said,

February 20, 2020 @ 3:53 am

"Used in mathematics" probably isn't accurate. It's true that there is a mathematical concept known as an inflection point or point of inflection, but "inflection point" in American vernacular english is completely disconnected from that concept. If you looked at a graph, you'd have a hard time seeing where the inflection points (in the mathematical sense) were.

I tend to suspect that the term you describe is borrowed from the vernacular use and not the mathematical use, especially given your translation of it as "turning point".

(For the technically minded: a point where a graphed curve stops going up and starts going down is known in mathematics as a "maximum", logically enough. An "inflection point" is a point where the curve stops accelerating and starts decelerating, or vice versa, but it can do that without ever changing direction. By a technicality of the definition, every point on a straight line is an inflection point. [Though usually you would talk about them in the context of other sorts of curves, where most points aren't inflection points.])

Philip Taylor said,

February 20, 2020 @ 6:05 am

This Google n-gram search suggests to me that the vast majority of instances of "pandit" are in collocation with "Nehru". Factoring these out, "pundit" appears more than twice as common as "pandit". Peak "pandit" usage occurred in 1952, the year in which Nehru was first elected as Prime Minister (as opposed to Interim Prime Minister). A similar search suggests that "Pandit" was many many times more common than "pandit" (case-senstive), and that "pundit" has always been more common than "pandit".

ajay said,

February 20, 2020 @ 6:47 am

pundit About 29,700,000 results

pandit About 66,600,000 results

Probably because "Pandit" is a common surname in India, and "Pundit" isn't.

If you filter out upper-case results "pundit" you get about 27.1 million results. (Presumably it is filtering out a lot of cases where "pundit" is capitalised because it's at the start of a word.)

If you do the same for for "pandit", you get 30 results on Google. Not 30 million; 30.

Victor Mair said,

February 20, 2020 @ 9:11 am

The webmaster of Pinyin.info, where "danger + opportunity ≠ crisis" was published, estimates that the page views for that article over the past fourteen years now total *well* over a million.

Victor Mair said,

February 20, 2020 @ 9:11 am

OT discussion on "pandit" vs. "pundit": I guess a lot of the difference depends upon whether one has an Indian studies background.

Sanskrit paṇḍita पण्डित.

"The Law of Hobson-Jobson", by Eveline Chao, LARB, China Channel (12/19/17)

Hobson-Jobson pundit

Hobson-Jobson pandit

Wikipedia pandit

Wikpedia pundit

Pandit, aka: Pandut, Paṇḍit (Wisdom Library)

Google does not yet encompass the whole of the universe.

ajay said,

February 20, 2020 @ 11:04 am

"Google does not yet encompass the whole of the universe."

Victor Mair said,

February 19, 2020 @ 10:50 pm

pundit About 29,700,000 results

pandit About 66,600,000 results

Daniel Barkalow said,

February 20, 2020 @ 11:57 am

In conjunction with "propagandists", I assumed "pandit" was used an a portmanteau of "pander" and "pundit", rather than referring to people who literally chant mantras, but not commonly in the PRC (and are not known for changing mantras based on current events).

Victor Mair said,

February 20, 2020 @ 12:37 pm

There are a lot of things I hear and see every day that do not show up in a Google search.

richardelguru said,

February 20, 2020 @ 12:40 pm

Your epicentric comment above (and Mark Libermans post of a few days ago) reminded me of a correction in the science magazine New Scientist some fifteen years ago—a correction of their misuse, in an even earlier edition, of 'epicentre': they had printed that the recent quake's "epicentre was 10 kilometers below the surface".

Just goes to show, but I'm not sure what…

Ellen K. said,

February 20, 2020 @ 1:02 pm

What struck me seeing that is that, in citing Kennedy, they are not citing an authority on the subject, and thus not making any proper claim of the accuracy of the information. I

The design of the graphic, though, does not suggest they are presenting it as an error.

Y said,

February 20, 2020 @ 2:56 pm

To Mchael Watt: It is a technical term. Numerous mathematic terms were translated into Chinese in the past hundreds of years, both in premodern and modern times. For example, in the Ming dynasty, Matteo Ricchi and Xu Guangqi co-authored a book on geometry. The concept of geometry was translated into Chinese as 几何. 几何 originally in Chinese did not mean geometry at all. I would say the original meaning of 拐点 is a vernacular expression of a turning point of any sort: e.g. a directional turn. But the Chinese used this term to designate the concept of "inflection point" in mathematics.

KevinM said,

February 20, 2020 @ 3:20 pm

As a Berliner, JFK would have been unfamiliar with Chinese characters.

Christel Davies said,

February 20, 2020 @ 4:26 pm

Panda + Bandit = Pandit

Gali said,

February 21, 2020 @ 3:43 am

RE: pandit vs pundit, I would personally reserve pandit for the original, respectful appellation, and leave pundit to predominantly signify blowhard commentators, which I believe (without any evidence) was much of the motivation for having a second borrowing of the term.

John Swindle said,

February 21, 2020 @ 3:45 am

The Chinese word 危機/危机 wéijī 'crisis' is written with the characters 危 wéi as in 危險 (危险) wéixiǎn 'danger' and 機 (机) jī as in 機會 (机会) jīhuì 'opportunity.' The idea that 機 (机) in itself means "opportunity" isn't far-fetched, it's just wrong. When this came up in 2009 I explained that the Chinese term for "crisis" meant "dangerous airplane." Check the Radar Range!

JK said,

February 21, 2020 @ 6:17 am

This phrase 化危为机 is being used in the context of the outbreak and appears to explicitly refer to "opportunity." It doesn't seem the online dictionaries have any information on the origins of this phrase though. Sometimes the characters are even put in quotation marks like 化“危”为“机”.

RP said,

February 21, 2020 @ 7:11 am

I think a pundit, writing ill-informed and scaremongering pieces about a pandemic, could happily be called a pandit.

Victor Mair said,

February 21, 2020 @ 8:58 am

pandit ≠ pundit ?

Antonio L. Banderas said,

February 21, 2020 @ 9:17 am

According to the OED,

Pandit: variant of pundit n.

Pundit:

a.a A learned Hindu; one versed in Sanskrit and in the philosophy, religion, and jurisprudence of India.

The Pundit of the Supreme Court (in India) was a Hindu Law-Officer, whose duty it was to advise the English Judges when needful on questions of Hindu Law. The office became extinct on the constitution of the ‘High Court’ in 1862. In Anglo-Indian use, pundit was applied also to a native Indian, trained in the use of instruments, and employed to survey regions beyond the British frontier and inaccessible to Europeans. ‘The Pundit who brought so much fame on the title was the late Nain Singh, C.S.I.’ (Yule.)

b.b transf. A learned expert or teacher.

Hence ˈpunditly adv. (nonce-wd.), in the manner of a pundit, in a learned way; ˈpunditship, the position or office of a pundit; Hindu scholarship.

Antonio L. Banderas said,

February 21, 2020 @ 9:18 am

According to the OED, pandit is a variant of pundit n.

Pundit:

a.a A learned Hindu; one versed in Sanskrit and in the philosophy, religion, and jurisprudence of India.

The Pundit of the Supreme Court (in India) was a Hindu Law-Officer, whose duty it was to advise the English Judges when needful on questions of Hindu Law. The office became extinct on the constitution of the ‘High Court’ in 1862. In Anglo-Indian use, pundit was applied also to a native Indian, trained in the use of instruments, and employed to survey regions beyond the British frontier and inaccessible to Europeans. ‘The Pundit who brought so much fame on the title was the late Nain Singh, C.S.I.’ (Yule.)

b.b transf. A learned expert or teacher.

Hence ˈpunditly adv. (nonce-wd.), in the manner of a pundit, in a learned way; ˈpunditship, the position or office of a pundit; Hindu scholarship.

Gali said,

February 21, 2020 @ 9:19 am

@Victor Mair A pandit could certainly be referred to as a pundit, at least in a historical context, but I would gall at calling most people who are described as pundits pandit. Which I suppose makes it a hyponym, though I suppose there are many people familiar with the word pundit who are unaware of the original meaning or otherwise make much conscious association with it (pundit in my lexicon, as I mentioned, is not "respected expert" but "opinionated loudmouth", and doesn't recall scholars and wise men unless the context demands).

Alex said,

February 21, 2020 @ 10:09 am

I was hoping it was dying out, too, but I just encountered it in Jared Diamond's 2019 book Upheaval. I groaned aloud. I probably shouldn't have expected better given his general approach to covering areas of knowledge that already have well-developed disciplines dedicated to their study.

Angelos Chaniotis said,

February 24, 2020 @ 3:44 pm

What I was saying in my talk (which was about the ancient Greek concept of crisis) is that Kennedy used a wrong etymology and explanation of the Chinese signs.

No further comments required.

Angelos Chaniotis

Eric Lessard said,

March 2, 2020 @ 4:24 pm

in re: Danger+Opportunity… dictionary says it’s true

When I started seeing the danger/opportunity thing years ago, I instinctively disbelieved it, simply because it had popped up in the culture in the manner of a hoax.

Later, in China on business, I recalled the 危机 claim and looked up the characters in whatever early 00’s electronic dictionary I had on hand. To my surprise, it offered “opportunity” as a translation for 机.

Seeing now that the estimable Dr. Mair had opined differently, I just now looked the character up on wiktionary and see that it gives “opportunity” as one meaning for 机, in both Chinese and Japanese.

What’s going on here?

Victor Mair said,

March 2, 2020 @ 10:28 pm

Go back and read "danger + opportunity ≠ crisis: How a misunderstanding about Chinese characters has led many astray" (Pinyin.info [2009]), the long, detailed article at the end of the list of "Readings" above. Don't just rely on simple dictionaries, which are often wrong when it comes to the analysis of individual morphemes.

See also my next post, which will approach the problem of "danger + opportunity =/≠ crisis" from a unique angle.

Rose Eneri said,

March 4, 2020 @ 3:39 am

After reading much about what the second Chinese character doesn't mean, I wish it had not taken me so long to ferret out what it actually does mean.

From the 6th paragraph of Professor Meir's September, 2009 post "How a misunderstanding about Chinese characters has led many astray" (Pinyin.info [2009])

"The jī of wēijī, in fact, means something like “incipient moment; crucial point (when something begins or changes).”

And the following paragraph adds: "To be specific in the matter under investigation, jī added to huì (“occasion”) creates the Mandarin word for “opportunity” (jīhuì), but by itself jī does not mean “opportunity.”

Rosen Eneri said,

March 4, 2020 @ 3:41 am

My apologies, Professor Mair for misspelling your name in my previous post.

Rose Eneri said,

March 4, 2020 @ 3:46 am

My apologies to Professor Mair for misspelling his name in my prior comment.

Rose Eneri said,

March 4, 2020 @ 3:53 am

BTW, I love how the on-line Wall Street Journal gives a commenter 5 minutes to edit a comment. Sometimes, we just can't see an error until it posts.