Greasiness, awkwardness, slothfulness, despondency — Chinese memes of the year

« previous post | next post »

The first two conditions, along with eight others, are covered in this interesting Sixth Tone article:

"An Awkward, Greasy Year: China’s Top Slang of 2017 " (12/28/17) by Kenrick Davis

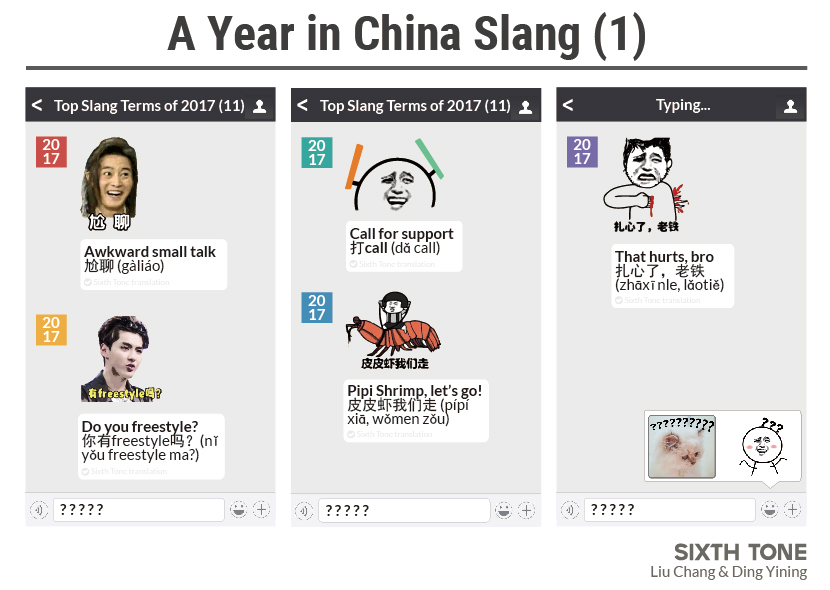

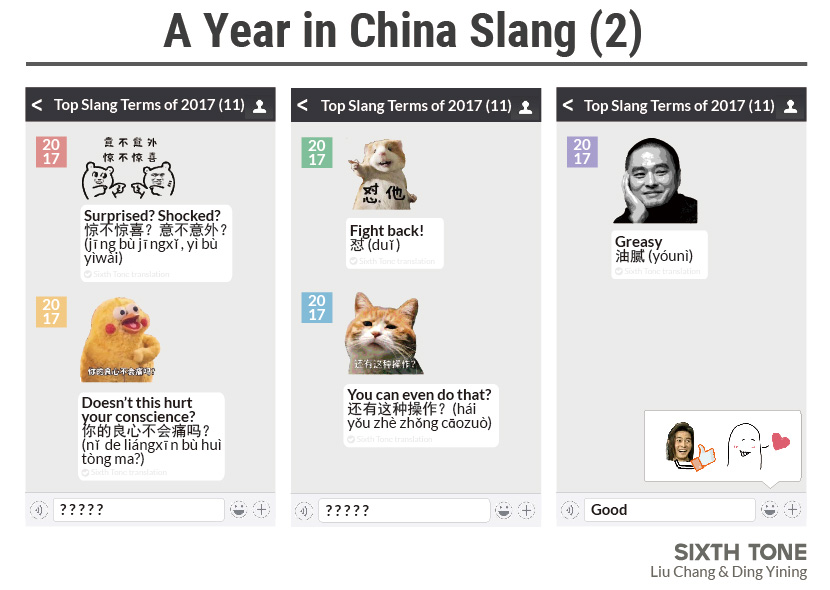

Davis's presentation is excellent, so let us begin this post with two montages accompanying his article.

Here are the ten cultural memes in Language Log style (but following Davis' translations), with a few added notes:

1. gàliáo 尬聊 ("awkward small talk")

We studied this word in great depth in this post: "GA" (8/6/17). Note that it is derived from the disyllabic morpheme, gāngà 尴尬 ("awkward; embarrassed"), so technically neither of the syllables means anything by itself.

2. nǐ yǒu freestyle ma? 你有freestyle吗?("do you freestyle?")

"Freestyle" here has nothing to do with swimming, but rather refers to the mixing of English and other languages in with Mandarin when rapping, as we saw in this post: "Chinese pentaglot rap " (12/28/17).

3. dǎ call 打call ("call for support")

We looked at this expression extensively in "East Asian multilingual pop culture " (10/31/17)

4. Pípí xiā, wǒmen zǒu 皮皮虾我们走 ("Pipi Shrimp, let’s go!")

Roughly equivalent to "Hi, ho, Silver, away!"

5. zhāxīn le, lǎotiě 扎心了,老铁 ("That hurts, bro.")

Lǎotiě 老铁 (lit. "old iron", i.e., "bro") is a northeasternism.

6. jīng bù jīngxǐ, yì bù yìwài 惊不惊喜,意不意外 ("Surprised? Shocked?")

Note the manner of forming choice questions here by truncating the first iteration of the repeated stative verbs separated by the negative bù 不.

7. nǐ de liángxīn bù huì tòng ma? 你的良心不会痛吗?("Doesn’t this hurt your conscience?")

Based on the fact that, of the two greatest Tang period poets, Du Fu (712-770) wrote fifty verses dedicated to Li Bo (701-762), whereas Li Bo only addressed a few poems to Du Fu, though this is very much in keeping with what we know about their personalities.

8. duì 怼 ("fight back!")

The verb more overtly means "resent; abhor".

9. hái yǒu zhè zhǒng cāozuò 还有这种操作?("You can even do that?")

The verbal noun at the end actually means "manipulation".

10. yóunì 油腻 ("greasy")

I learned this word in the first year of my Chinese studies. To me, way back then, it meant "unctuous; oily; ingratiating". In its current incarnation, yóunì 油腻 began by signifying a greasy, dirty, sleazy, unkempt middle-aged man who likes to put down younger people, but it soon was applied to middle-aged, gossipy women and even young people who are fond of showing off on social media.

Around the same time that I read the article in Sixth Tone described above, I also read an article by Wang Xiaoyu in Caixin that covered some of the same ground, but focused on different words:

"Has 'Sang' Become the Defining Character of Chinese Millennials? Buzzword adopted by youth to express despondency may hint at a larger social problem" (12/29/17)

[VHM: "sang" here is not pronounced as the past tense of "sing", but rather as "sawng" or "sahng".]

Here are the opening paragraphs:

Looking back at 2017, a growing sentiment of despondency has overshadowed China’s public discourse, especially among millennials.

This year’s internet buzzwords reflect the changing attitudes of Chinese netizens — from the ubiquitous “zheng neng liang,” or positive energy, to the pursuit of “little but certain happiness,” or “xiao que xing,” and then to the current rise of the melancholy “sang” culture.

The Chinese character “sang,” which is usually associated with funerals, can be roughly translated into mourning, nursing a sense of loss or being dispirited. This gloomy word has long been intentionally avoided in daily use, but now it has become a trending term to depict the dim views among young people about their career or marriage prospects.

A typical icon of sang culture is a tea chain called Sung Tea selling drinks labeled “achieved-absolutely-nothing black tea” or “my-life-is-a-waste green tea.” These tongue-in-cheek titles reflect the sense of demotivation, apathy or low self-esteem that has grown pervasive among Chinese millennials.

The prevalence of Sang culture came to light after several seemingly dull internet memes spread like wildfire. One such image, which went viral in 2016, showed a middle-aged man slouched on a couch with a look of resignation etched on his face. It was a screenshot from a 1993 sitcom “Love My Family,” starring actor Ge You, and prompted a wave of photos mimicking the gesture that is now known as the “Ge You slouch.”

The main internet buzzwords analyzed in this article are:

- sàng 丧 ("funeral; mourning", but meaning "despondency" in current parlance)

- zhèng néngliàng 正能量 ("positive energy"), promoted by the government

- xiǎoquèxìng 小确幸 ("little but certain happiness"), a middle ground between 1. and 2.

The derivation of 3. is described in Wiktionary thus:

Borrowed from the Japanese wasei kango (和製漢語, Japanese-made Chinese words) term 小確幸 (shōgakkō), from 小 (shō, “little”) + 確 (kaku, “sure”) + 幸 (kō, “fortune”), which was first used by Japanese writer Haruki Murakami in Afternoon in the Islets of Langerhans (ランゲルハンス島の午後, 1986).

I wrote a post about some of these issues here:

"The cult(ure) of slothful losers" (6/28/17)

What do all of these words boil down to? First of all, much as it tries and wishes it could, the government cannot force the people to be happy and optimistic. Second, the borrowing of foreign words continues apace. Third, Chinese netizens are wonderfully creative and possessed of a fine sense of satire. We can look forward to a new batch of internet memes in 2018 and in the years beyond.

[h.t. Caitlin Schultz and John Rohsenow]

david said,

December 31, 2017 @ 7:31 am

Take it easy

Go greasy

Bouchillon 1926

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=u9No8th4q90

Victor Mair said,

December 31, 2017 @ 9:12 am

And here's what Xi Jinping wants the New Year's buzzwords to be like:

"Buzzwords from Xi's new year greetings"

chinadaily.com.cn | Updated: 2017-12-31 06:40 f

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201712/31/WS5a4815f1a31008cf16da462f.html

Note that Facebook, Twitter, and all other Western social media are banned in China, but the CCP uses them to spread its propaganda worldwide.