Pinyin in 1961 propaganda poster art

« previous post | next post »

From Geoff Dawson:

On display in a current exhibition at the National Library of Australia.

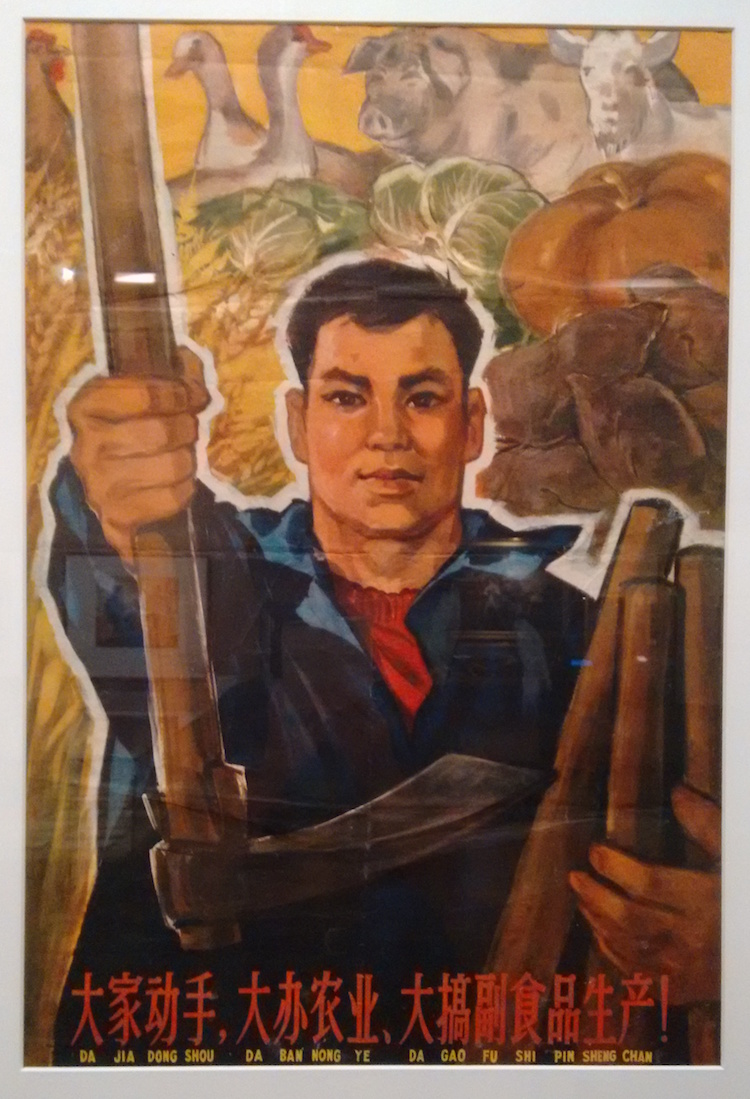

The wording at the bottom reads as follows, in characters and in Pinyin:

Dàjiā dòngshǒu, dà bàn nóngyè, dà gǎo fù shípǐn shēngchǎn!

大家动手,大办农业,大搞副食品生产!

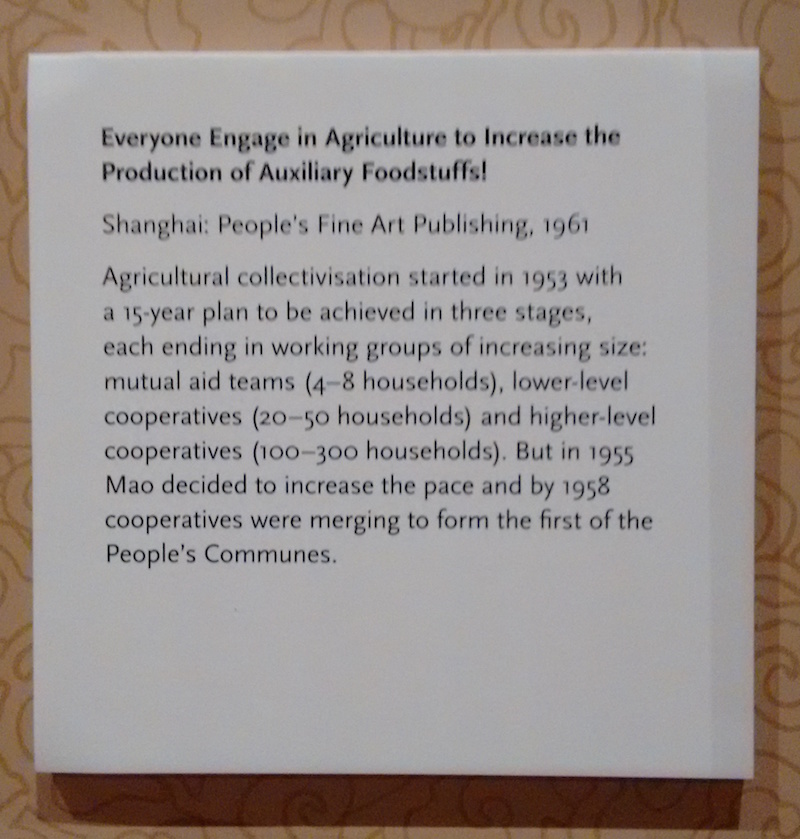

Here's the English translation on the label accompanying the poster:

While the translation is not entirely faithful to the Chinese original, it is adequate, so I won't provide an alternative version.

What merits pointing out about the Pinyin are mainly two things:

- it lacks tones

- it does not follow the orthographic rules for parsing into words, nor does it include punctuation

It is not surprising that the slogan is just written out syllable by syllable, with a space between each syllable, since the official rules for Hànyǔ pīnyīn zhèngcífǎ 汉语拼音正词法 ("Hanyu Pinyin Orthography") were only drafted in 1982 and promulgated in October of 1984. This was a very heady time for my friends at the Wénzì gǎigé wěiyuánhuì 文字改革委员会 ("Script Reform Committee"), since they believed that, with these rules, China was taking a giant step forward toward Hanyu Pinyin as an alternative to Chinese characters (Hànzì 汉字) in a functional digraphia.

But this was not to be. For the reasons why, see:

"Words in Mandarin: twin kle twin kle lit tle star" (8/14/12) — especially in the comments.

Here's the latest version (2012) of the orthographic rules. An English translation (by John Rohsenow) of the previous edition (1996) of the orthographic rules is printed at the back of all ABC Chinese-English dictionaries from the University of Hawai'i Press.

Of course, In the previous century and more of experimentation with romanization, various schemes for indicating the joining of syllables into words were put forward, both in China and abroad. But Hànyǔ pīnyīn zhèng cífǎ 汉语拼音正词法 ("Hanyu Pinyin Orthography") was the first official set of rules for writing Mandarin with the alphabet promulgated by a Chinese government. Indeed, it still is, and it is entirely possible that — with new blood in applied linguistics circles — it may once again offer the possibility of providing the second leg of a two script system for China.

Neil Kubler said,

December 29, 2017 @ 9:30 pm

Don't mean to be a spoilsport, but shouldn't "Hànyǔ pīnyīn zhèng cífǎ" be written "Hànyǔ pīnyīn zhèngcífǎ"?

Bloix said,

December 29, 2017 @ 9:38 pm

This poster dates from the latter part of the Great Chinese Famine of 1959-1961, caused by a combination of bad weather, forced collectivization, and imposition of the doctrines of the Russian quack Lysenko, and horribly exacerbated by cruel and stupid distribution policies that starved the rural areas. At least 20 million people died, and perhaps twice that. The poster is presumably part of the cover-up.

Chris Button said,

December 29, 2017 @ 11:48 pm

The approach reminds me of bopomofo in Taiwan or furigana in Japan albeit underneath rather than on top.

Victor Mair said,

December 30, 2017 @ 12:38 am

And look at the tool that he is handing out: it is an adze, the most primitive all-purpose tool known to humankind. See the woodcut illustration by Dan Heitkamp on the title page of Victor Mair, tr. and intro., The Art of War: Sun Zi's Military Methods (Columbia University Press, 2007). This is the source of the Chinese character bīng 兵 ("weapon" > "soldier").

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E5%85%B5

Mark Hansell said,

December 30, 2017 @ 10:22 am

Slight terminological correction– the tool is not an adze (a woodworking tool), but a similarly-shaped mattock, or digging hoe. And though they may be ancient, in skilled hands they are very efficient tools for digging and shaping earth (especially in constructing and altering the little dikes between rice paddies.)

Victor Mair said,

December 30, 2017 @ 11:04 am

@Neil Kubler

Thanks for catching that. I've corrected it in the o.p. (zhèng cífǎ –> zhèngcífǎ) Usually that's the way I write it:

zhèngcífǎ 正词法 ("orthography")

Comments by Mark Swofford, master of all things Pinyin:

=====

As I often note, three-syllable compounds are among the trickiest to know how to parse. As a general rule, I don't like bound morphemes being written separately, which is sometimes helpful in making parsing determinations. Note that capitalization of proper nouns and typographical indication of titles (e.g., italic [which I usually avoid when tone marks are employed], guillemets) also help comprehension.

fēijīchǎng 飞机场 ("airport")

Fǎlún Gōng 法轮功 (it already seems standardized as such)

dǎzìjī 打字机 ("typewriter")

Hónglóu Mèng 红楼梦 (Dream of the Red Chamber) (as also given by YBY in his Xinhua Pinxie Cidian)

Victor Mair said,

December 30, 2017 @ 11:33 am

From Endymion Wilkinson:

How did the 2012 GB standard (16159-2012) alter the rules for pinyin orthography? A quick comparison of the 2012 standard with the previous 1996 standard reveals that the 2012 standard adopts almost all what was laid down in 1996 but rearranges the categories; alters a few, and adds some useful precisions.

Detail: Years such as 二〇〇八年 should be written er ling ling ba nian (I have left out the tone marks in this and what follows); month + day references such as 五四 should be hyphenated, viz wu-si; a range of numbers such as 三五天 should be hyphenated, viz san-wu tian; also in the realm of hyphens, 南北朝 should be written Nan-Beichao and 沪宁杭 should be written Hu-Ning-Hang; set phrases which are not 4-character phrases should be divided by words, e.g., bei heiguo 背黑锅; foreign personal and place names should be written in pinyin, then in Chinese characters, and then in their original form, e.g., Makesi (马克思, Marx); this is a welcome change to the 1996 rules, but note the rule also gives as an example Dongjing (东京, Tokyo), i.e., macrons are left off the "original"; tone marks should be shown on onomatopoeias; there are also new rules re initialisms and other abbreviations; finally there are detailed instructions how to break pinyin words at line endings (e.g., if Xi in Xi'an comes at the line end it should be written Xi-.

Victor Mair said,

December 30, 2017 @ 12:12 pm

@Mark Hansell

Thanks for pointing out that the man is proffering a mattock, not an adze.

It's true that, in modern terminology, the mattock is for digging in the dirt and adzes are more for woodworking. But I think that the earliest bīng 兵 in China were multipurpose, and they did not make a distinction between use as a woodworking or digging tool and as a weapon.

Adze

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adze

Images here and here.

Mattock

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mattock

Images here and here.

DD'eDeN said,

January 4, 2018 @ 5:14 pm

Thanks for 'digging into' the adze/mattock/bīng 兵 history. My research indicates that unlike the extremely ancient hand-axe & later hafted axe, the adze was a "recent" invention, sometime between 50,000 and 20,000 years ago in Papua, people made pancake flour from Sago palm from pounded & scraped pith, leaving a rind in the form of a small dugout canoe, this was the origin of the mattock/adze & bark-skin boat and then dug-out canoe (and probably earliest flour) in my opinion.