Lin Tianmiao's "Protruding Patterns": sexism in Chinese characters

« previous post | next post »

Article by Sarah Cascone in Artnet (October 16, 2017):

This Artist Gathered 2,000 Words for Women—and Now, She Wants You to Walk All Over Them: Lin Tianmiao's installation at Galerie Lelong puts contemporary language on top of antique carpets."

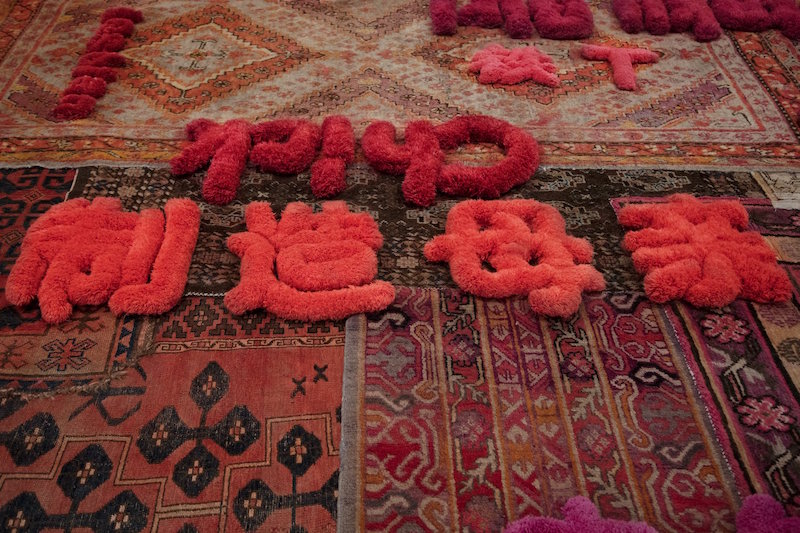

Here's an example of Lin's work:

The puffy Chinese characters in the center read:

zhìzào mǔqīn 制造母亲 ("manufacturing mother[hood]")

Above that, inverted, is the English word "Chick".

I showed just this photograph, but not the article, to a female Chinese friend. Here is her reaction:

I think it means "to manufacture a mother." There is, however, no such a phrase in Chinese. We never say "zhìzào mǔqīn 制造母亲", but "zhìzào chǎnpǐn 制造产品", to manufacture a product. Does it mean women are required and even forced to become mothers by the society and the culture?* I notice there are other words on this artwork, such as tiěT 铁T ("iron T") and lesbian. Maybe it is about the social status of women. All these words are on a carpet. Does it mean they are something that people trample on? They are all in pink, a feminine color, and made of a comfortable material, maybe a metaphor for their fragility?

In traditional societies, such as China, there is discrimination against unmarried women and those who do not have children. Japanese society is an interesting example. I happened to see a Japanese documentary film about single mothers living in poverty. Japanese girls are trained to be a good wife and good mother since childhood. Many of them resign after marriage. Therefore, they can hardly find a job once they get divorced. Ironically, Japan is experiencing very low birth rate, and their young people even do not want to get married.

[*VHM: Or is it a reference to the commodification of motherhood?]

From another Chinese woman:

From a Chinese man:

I would guess that "manufacturing mother" refers to the activities of people comparing the homeland, the nation, or the party as his / their mother.

From the article by Sarah Cascone:

The Chinese artist has created a gallery-filling installation made entirely of antique carpets. Stitched together, they are embroidered with dozens of words about women in Chinese, English, French, and other tongues—a selection of some 2,000 phrases the artist has collected over more than five years.

“The negative words are obviously more pronounced,” Lin admits to artnet News of the often-sexist lexicon, which ranges from obscure sexual slang (“hamburger”) to terms of endearment (“goddess”).

Seeing Lin Tianmiao’s "Protruding Patterns", I cannot help but think of Nancy Sinatra's epochal "These Boots Are Made for Walkin'".

These boots are made for walkin', and that's just what they'll do

One of these days these boots are gonna walk all over you.

References

- "Misogyny as reflected in Chinese characters" (12/24/15) (includes references to other relevant posts and articles)

- Kaitlyn Ugoretz, "Script in the Margins: Representations of Women in Early Premodern Chinese Orthography" (April, 2017; full text of thesis available as a pdf here)

[h.t. Ben Zimmer; thanks to Jing Wen and Jinyi Cai]

Victor Mair said,

October 26, 2017 @ 10:17 am

From Zhang He:

Context for zhìzào mǔqīn 制造母亲 ("manufacturing mother[hood]"):

Hu Shih 胡适 published an article in the 1920s encouraging opening schools for women (nǚ xuétáng 女学堂)。One of the reasons is that educated women could be better mothers. In the article he used exactly the term: “zhè nǚ xuétáng biàn shì zuì hǎo de zhìzào mǔqīn de dà zhìzào chǎng 这女学堂便是最好的制造母亲的大制造场。”("These schools for women are the best large production facilities for producing mothers").

Victor Mair said,

November 7, 2017 @ 4:08 pm

Additional remarks from Zhang He:

I am a little particular about the carpets Lin used for this piece of work. Although she did not explain about the carpets, from the interviewer, readers get impressions that, 1) they are “Chinese carpets”; and 2) they are women’s work. In fact, neither is correct.

I wonder if Lin herself recognizes that most of these carpets, if not all, are Xinjiang or simply Khotan carpets, which are normally labeled as China Xinjiang carpets since 1950s, or known as the carpets from East Turkestan before 1949, which has unique design traditions of its own. They are very much different from those made in Hebei (河北) which developed very late in history and carry mostly Sinicized designs. Xinjiang carpets are still exotic to most ignorant Han Chinese even today. In history, except for being exotic goods and luxury for the royal courts, Chinese did not and still do not favor these carpets for daily use.

Viewers like me or those from Xinjiang, could be sensitive to the carpets used in Lin’s work and get a different response from those of general audience. To me, Lin seems to use the carpets simply as floor covering for its material and functional value, or as women’s production and its feminine quality. But I see these carpets as having a strong cultural background and history that relates directly to Xinjiang/Khotan. The designs are so particularly Xinjiang/Khotan that they could and should play some role of significance.

So I wish I could know the intention of the artist: if she knows the sources of the carpets and intentionally make a cultural connection between the minority carpet-makers in Xinjiang and the majority Han Chinese and even imperial royalties (if so, I am afraid most audience would definitely not get her intention), or if she does not know the sources, but randomly combined Xinjiang carpets and Chinese characters and Roman letters to create a bizarre harmony (the colors of her embroidered characters and letters are harmoniously fitted with the colors of the carpets).

Lin mentions that some of the motifs in the carpet design have influence from the west. I wonder what kind of “west” she implies. If she meant Greco-Roman influence, that would be too far back in history. There are carpets of 3rd to 5th century CE found in Khotan that already carry clear Greek and Roman design patters of pottery, wall or floor mosaics. If she meant modern time western influence, I am afraid she had seen some realistic images such as a church building. And these realistic representations were popular during mid and late Qing dynasty in about 18th and 19th centuries for special customers and their tastes, which is not surprising. I guess Lin’s collected carpets are of 19th and 20th centuries, not very ancient.

In Xinjiang/Khotan, as well as in many carpet-making workshops in Central Asia, carpets makers are not only women, but also men. Men and women might not sit together to work on one same carpet, but both work on their own looms. So, to specify it as women’s work is not really correct.

There are usually two ways to understand a work of art: 1) to understand the artist’s intention, and 2, to focus on audience’s responses. For Lin’s work, it is hard to guess what her intention was, but obviously more audience got interested in the word expressions.

It is interesting to see a few viewers’ responses to Lin’s work through VHM’s specific question about “manufacturing mother(hood)”. One viewer and Artnet News did try to interpret the meaning of the carpets, and both seem to see them as floor coverings for people to trample on. It might be the artist’s intention as well.

I agree with their kind of view only partially. Historically and still today in Xinjiang, carpets are used for bedding, floor covering, wall hanging, and also as dancing field, play stage, and guests gathering seating. In ordinary people’s house, a host and hostess will take out a carpet and unroll it for important guests and dear friends only. I experienced it at least twice in Xinjiang in recent years. Once when I went back to Khotan and visited a farmer’s house on the farm where I had been a re-educated youth, when the hostess carried out her (a Chinese woman who married to a Uighur husband) carpet from an inner room and spread on a wide bench (kang炕, or bed) under the grape-trellis; and once in a Kazak’s yurt (not those for tourists) in a pasture near Urumqi, when the hostess unrolled a knotted carpet (rug) over a normal felt-made covering (Kazak use felt more than woven carpets).

For me, even if the artist had the intention for the carpets to be trampled on in a humble low status, I, or people from Xinjiang, still value the carpets more, probably than the words. Carpets are soft and cozy. You trample on it yet not without respect. Like Roman floor mosaics, you could stand on a god’s head.

As for the words, or labels, for women, each label reflects a particular time period and cultural context, and each has particular stories to go with. In that, this art piece links history, a very rich one