Gorsuch v. Prepositional Phrases

« previous post | next post »

In the Wall Street Journal article "Supreme Court Nominee Takes Legal Writing to Next Level," Joe Palazzolo writes that Judge Neil Gorsuch, Donald Trump's nominee for the Supreme Court, has elevated legal opinions to "a form of wry nonfiction." Not only that, "his affinity for language reveals itself in other ways. Poorly drafted laws tend to summon his inner grammarian."

"We're all guilty of venial syntactical sins. And our federal government can claim no exception," Judge Gorsuch wrote in a 2012 dissent, which went on to critique a provision of federal sentencing guidelines "only a grammar teacher could love," with its "jumble of prepositional phrases."

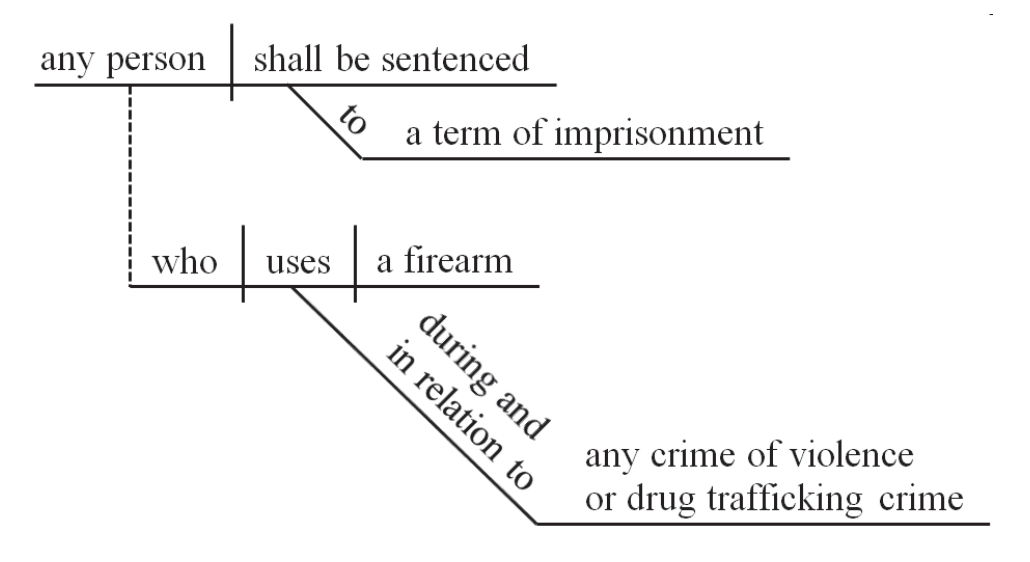

In a 2015 opinion, Judge Gorsuch hacked through another "bramble of prepositional phrases" to figure out how to apply a criminal law that heightens penalties for using a gun in the commission of a crime. In what might have been a first, he diagramed the sentence containing the provision in question and illustrated his opinion with it.

Gorsuch's focus on linguistic particularities has earned him comparisons to the late Antonin Scalia, whose vacancy on the bench he would be filling. But Scalia never went as far as including a sentence diagram in an opinion, as far as I know. Here's a longer excerpt from the 2015 case that excited his inner grammarian, United States v. Rentz:

Few statutes have proven as enigmatic as 18 U.S.C. § 924(c). Everyone knows that, generally speaking, the statute imposes heightened penalties on those who use guns to commit violent crimes or drug offenses. But the details are full of devils.

Originally passed in 1968, today the statute says that "any person who, during and in relation to any crime of violence or drug trafficking crime … uses or carries a firearm, or who, in furtherance of any such crime, possesses a firearm, shall, in addition to the punishment provided for such crime … be sentenced to a term of imprisonment of not less than 5 years." 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A).

That bramble of prepositional phrases may excite the grammar teacher but it's certainly kept the federal courts busy. What does it mean to "use" a gun "during and in relation to" a drug trafficking offense? The question rattled around for years until Bailey v. United States, 516 U.S. 137, 116 S.Ct. 501, 133 L.Ed.2d 472 (1995), and even now isn't fully resolved. What does and doesn't qualify as a "crime of violence"? The better part of five decades after the statute's enactment and courts are still struggling to say. Cf. United States v. Castleman, — U.S. —, 134 S.Ct. 1405, 188 L.Ed.2d 426 (2014); United States v. Serafin, 562 F.3d 1105, 1110-14 (10th Cir. 2009).

And then there's the question posed by this case: What is the statute's proper unit of prosecution? The parties before us agree that Philbert Rentz "used" a gun only once but did so "during and in relation to" two separate "crimes of violence"—by firing a single shot that hit and injured one victim but then managed to strike and kill another. In circumstances like these, does the statute permit the government to charge one violation or two?

Here is the Reed-Kellogg-style sentence diagram that Gorsuch includes later in the opinion:

I'll leave the evaluation of his syntactic argument to others — you can read the whole opinion here. I'll just note that, as Mark Liberman observed in 2013, "the Reed-Kellogg method of 'diagramming' sentences has been intellectually obsolete for a hundred years."

The other opinion mentioned in the Wall Street Journal article, his 2012 dissent in U.S. v. Rosales-Garcia, can be found here. An excerpt follows below.

Of course, we're all guilty of venial syntactical sins. And our federal government can claim no exception. Which takes us to USSG § 2L1.2(b)(1) and this jumble of prepositional phrases—

If the defendant previously was deported, or unlawfully remained in the United States, after—(A) a conviction for a felony that is (i) a drug trafficking offense for which the sentence imposed exceeded thirteen months … [add a sentencing enhancement].

This has to be a sentence only a grammar teacher could love. We have here our old nemesis the passive voice, followed by a scraggly expression of time ("previously … after"), then a train of prepositional phrases linked one after another and themselves rudely interrupted by a pair of parenthetical punctuations.

Happily, our role isn't to grade the grammar, only discern the meaning. And often a speaker's meaning can be clear even when his grammar isn't. We know from context what the child means when talking about the telescope (because background knowledge tells us, say, that the child has a telescope and the man and hill do not). Context likewise explains what the newspaper is getting at (because, for example, the first sentence of the article makes clear the brothers hadn't seen each other in years). Even when the grammar's gnarled, meaning often can be straightforward enough.

And that well describes this case. At first blush, one might wonder whether only a conviction for a drug trafficking felony must precede a defendant's deportation—or whether the conviction and the imposition of a full 13 month sentence must both predate the deportation. The grammar and language of the guideline provision before us supply ample support for each of these competing readings. But, as with much in life, when we bother to consult the directions (the relevant context in this case), what at first appears confusing proves disarmingly simple.

Regardless of his judicial reasoning, I can appreciate why this dissent was a 2012 Exemplary Legal Writing honoree from The Green Bag (the "Entertaining Journal of Law").

Update, Feb. 5: I spoke briefly about Gorsuch's sentence diagram on NPR's Weekend Edition.

Guy said,

February 1, 2017 @ 1:41 am

Slightly tangential, but the current case law is that if a gun is traded for drugs, the recipient of the drugs "used" the gun (they used the gun to buy the drugs), but the recipient of the gun did not (the government's argument that they "used" it as a medium of exchange was rejected).

Neal Goldfarb said,

February 1, 2017 @ 2:20 am

Diagramming the sentence in Rentz — whether using Reed-Kellogg or a tree diagram or anything else — was doomed to be an exercise in futility because there is simply nothing in the sentence that specifies what the unit of prosecution is.

Chad Nilep said,

February 1, 2017 @ 3:12 am

Why would passive voice be a nemesis here? Is this really better:

If a court previously deported the defendant, or the defendant unlawfully remained in the United States…

I don't see any difference in interpretation.

The length and complexity of the sentence is another matter.

Of course — as someone once said — we're all guilty of venial syntactical sins.

philip said,

February 1, 2017 @ 4:42 am

But at least he knows a passive when one is seen by him.

D.O. said,

February 1, 2017 @ 9:37 am

If the defendant previously was deported…

Call Prof. Pullum.

And can judges please stick to judging, a.k.a. deciding cases, not making pronouncements about prepositional voices and everything else under the sun? Answer: no.

Joseph Bottum said,

February 1, 2017 @ 10:08 am

At least here, in a dissent, he makes a grammatical point clearly and well:

"Mr. Games-Perez was prosecuted under 18 U.S.C. § 924(a)(2) for 'knowingly violat[ing]' § 922(g), a statute that in turn prohibits (1) a convicted felon (2) from possessing a firearm (3) in interstate commerce. But to win a conviction under our governing panel precedent in United States v. Capps (10th Cir. 1996), the government had to prove only that Mr. Games-Perez knew he possessed a firearm, not that he also knew he was a convicted felon. . . . [J]ust stating Capps's holding makes the problem clear enough: its interpretation — reading Congress’s mens rea requirement as leapfrogging over the first statutorily specified element and touching down only at the second listed element — defies grammatical gravity and linguistic logic."

The whole dissent (to a refusal of en banc rehearing) is here: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=4385270479132768131

J.W. Brewer said,

February 1, 2017 @ 10:59 am

Given that the context of myl's post about Reed-Kellogg being obsolete was a lament that no one in the wider world (very much including those who teach English and related subjects in the US from kindergarten through graduate school) are aware of more recent developments in ways to illustrate the syntactic structure of sentences, I guess the practical question is whether using an obsolete approach is better than using no approach. Although as noted above it may well be that the problem with the specific sentence is not ambiguity about how to understand its structure but ambiguity as to the referent of some of its language which is not resolved by a correct parsing of structure.

FWIW, I note that the Denver-based federal appellate court on which Judge Gorsuch currently sits handles among other things appeals from the lower federal courts in Utah, and thus needs with some frequency to handle issues of Utah state law that arise in federal court. This means Judge Gorsuch is much more likely than federal judges in other parts of the country to be aware of the work of (and perhaps also be socially acquainted with) the current members of the Utah Supreme Court, including Justice Lee, who I expect may be the only American judge of the twenty-odd names included on Mr. Trump's lists of potential SCOTUS nominees who has also been the subject of favorable Language Log posts praising his sophisticated grasp of corpus linguistics and how to use it as a tool for legal decisionmaking.

Jean-Sébastien Girard said,

February 1, 2017 @ 3:40 pm

I believe this may be the very first time an author quoted on LL complains about a passive voice AND IS ACTUALLY RIGHT. Call Satan, ask if he needs help getting his car out of that snowbank.

Guy said,

February 1, 2017 @ 4:17 pm

@Jean-Sébastian Girard

People have been quoted here correctly identifying the passive voice before. And honestly, it's not clear that there's any problem with it in that usage. The active counterpart seems pretty inappropriate here, honestly.

J.W. Brewer said,

February 1, 2017 @ 4:32 pm

The passive as such does not seem to be the problem with that particular sentence, although perhaps the lack of syntactic parallelism between passive-voice "was deported" and the structurally-parallel active-voice "or unlawfully remained" adds to the convoluted feel of the result. NB that that language is not from a statute produced by the Congressional sausage factory but from the Sentencing Guidelines (put out by the special-purpose Sentencing Commission) where there are at least arguably more process safeguards to ensure quality control.

Mark S said,

February 1, 2017 @ 9:36 pm

@J.W.Brewer:

Since this is Language Log, may I note that your sentence, above: "This means Judge Gorsuch … and how to use it as a tool for legal decisionmaking", while grammatically impeccable, left me somewhat out of breath.

AntC said,

February 2, 2017 @ 12:34 am

Since this amounts to an invitation for the "inner grammarian", could I ask:

Yes, those examples are jumbles/brambles of phrases/parentheticals/dependent clauses. But I don't see very many prepositions, and It's not the PPs that are problematic so much as the connectives/quantifiers/qualifiers (or lack of them/parataxis).

Full marks to Judge Gorsuch for knowing his passives. I wonder, though, if he can tell a Prepositional Phrase from a phrasal verb? ("sentenced to" is diagrammed wrong, methinks.)

Neal Goldfarb said,

February 2, 2017 @ 1:43 am

J.W. Brewer: I am in Utah for a conference at BYU Law School about law & corpus linguistics. Justice Lee will be there. Is there anything you'd like me to ask him?

Neal Goldfarb said,

February 2, 2017 @ 2:01 am

Joseph Bottum: Although I agree with Gorsuch's ultimate conclusion in Games-Perez, I think he's mistaken in basing the conclusion on grammar. In sec 924(a)(2), "knowingly" modifies "violate sec. 922(g)". Any grammatical analysis of the scope of modification has to be limited to the sentence in which "knowingly" occurs — unless you treat the relevant text from 922(g) as being implicitly incorporated by reference into 924. But while it's reasonable to read 924 as ifit incorporated 922, the incorporation is really just metaphoric (or something like that), not actual.

IMO Judge Gorsuch's conclusion follows simply from the semantics of the VP "knowingly violate [a specified statute]". However, there is some screwed up case law on this issue.

Michael Watts said,

February 2, 2017 @ 2:18 am

He's diagrammed it as a verb with a prepositional-phrase complement, and that seems right to me. To "throw something away" involves no (necessary) throwing, but getting "sentenced to penal servitude" is just a more specific variety of getting "sentenced". (And this is unfair, but try getting "sentenced penal servitude to" ;p )

I'm at a loss as to his problem with "previously … after". It seems pretty normal to indicate that something might have happened both (1) before now ("previously") and (2) "after" some other thing even further in the past.

George Williams said,

February 2, 2017 @ 2:18 pm

The sentence-diagramming exercise does no real work in US v. Rentz. The sentence immediately below the diagram ("Visualized this way, it's hard to see how the total number of charges might ever exceed the number of uses, carries, or possessions.") is irrelevant, since (i) neither the verb "uses" by itself nor the diagram does anything to hint at or characterize the number of uses, and (ii) what matters is use in relation to another crime. Figuring out how many other crimes there were and whether holding a gun during any or all of them should count as one or more uses is not resolved by this kind of analysis. In that regard, the opinion fails to consider the reference to "such crime" in analyzing the statute, a reference that points to the other crime in relation to which the gun is used, not the use itself.

psistrom said,

February 2, 2017 @ 2:25 pm

Joseph Bottum's comment has a link to Judge Gorsuch's opinion dissenting from the denial of rehearing en banc in the Games-Perez case. But I think that link is actually to the original panel decision in which Judge Gorsuch wrote a concurrence. Here's a URL for his dissenting opinion.

https://www.ca10.uscourts.gov/opinions/11/11-1011.pdf

Joseph Bottum said,

February 2, 2017 @ 11:07 pm

psistrom—Thanks for the right link!