Spelling with Chinese character(istic)s, pt. 3

« previous post | next post »

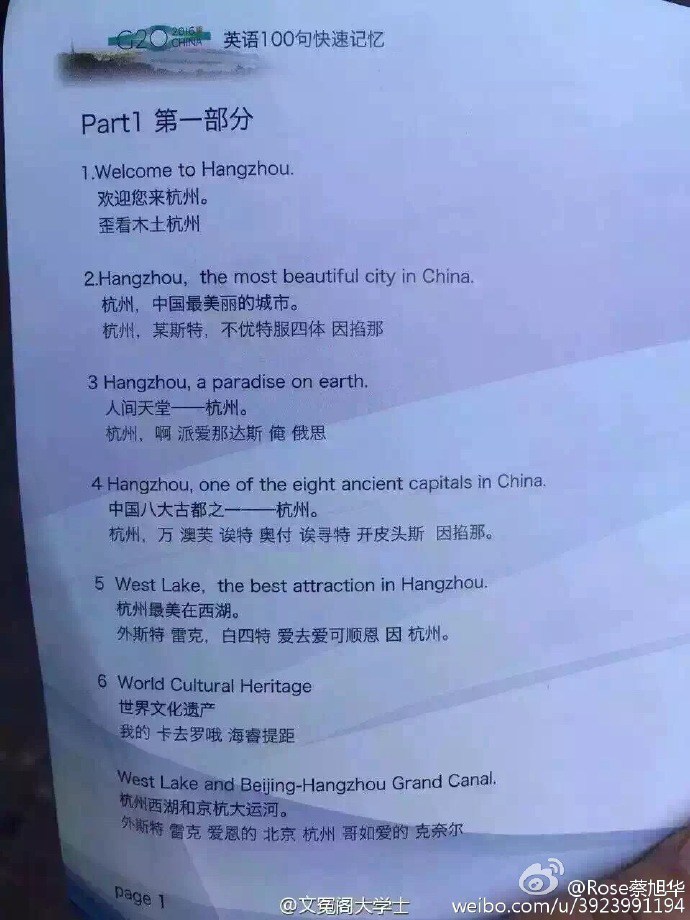

Hangzhou is handing out “crash course” manuals for residents to chat with international visitors at the G20 Summit in September, complete with Chinese character transcriptions of such beginner’s phrases as “Hangzhou, a paradise on Earth” and “orioles singing in the willows”:

To give an idea of how this "spelling with Chinese characters" works, here are the first and fifth entries of Part 1:

Welcome to Hangzhou.

huānyíng nín lái hángzhōu

欢迎您来杭州

wāikànmùtǔHángzhōu

歪看木土杭州

(lit. "crooked-look-wood-earth-

West Lake, the best attraction in Hangzhou.

Hángzhōu zuìměi zài Xīhú

杭州最美在西湖

Wàisītè léikè, báisìtè àiqù'àikěshùnēn yīn Hángzhōu

外斯特 雷克,白四特 爱去爱可顺恩 因 杭州

(lit., "outside-this-special thunder-overcome, white-four-special love-go-love-can-along-grace because Hangzhou")

In another section of the booklet, they have four character expressions for the "Ten Scenes of West Lake", such as this one:

Evening Bell Ringing at the Nanping Hill

Nánpíng wǎnzhōng

南屏晚钟

yīfùní bǎièr ruìyīn àitè zhè Nánpíng Hé'ér

一付呢 百二 睿因 艾特 这 南屏 何而

(lit., "one-pay-twitter hundred-two farsighted-because mugwort-special this Nanping what-and")

About the only positive thing I have to say for this type of transcription is that they sometimes — but by no means always — insert word spaces.

Some drawbacks:

- Much of it does not sound like English and will not elicit the intended words. I doubt that one in ten million visitors to Hangzhou will realize that àiqù'àikěshùnēn 爱去爱可顺恩 stands for "attraction". Will anyone realize that ruìyīn 睿因 stands for "ringing"? That shìruì 是瑞 (lit., "is Swiss / propitious") is meant to represent "three"?

- Cognitive dissonance; semantic interference (Russian interferentsiya интерференция).

- They could have used a lot more mouth radicals to signal that the syllable in question is purely transcriptional (represents sound only). For example, why use ài 艾 ("mugwort") when āi 哎 is available?

- Sometimes they simply drop words, e.g., "the" in sentence 2, but then, as in the last example cited, they turn around and use zhè 这 ("this") to represent "the". If they wish to develop a system of transcription based solely on Chinese characters, they should be consistent.

- Occasionally they are attentive to final consonants (e.g., pǎode 跑的 [lit., "run-of"] for "pond" and gērú'àide 哥如爱的 [lit., "brother-like-love-of" for "grand" — but what happened to the nasal in both of these words?), though usually they're dropping consonants all over the place.

- Even very simple, common, essential words like "lake" (léikè 雷克 [lit., "thunder-overcome"], lèikě 类可 [lit., "category-can"]) are transcribed differently in close proximity.

- Some of the transcriptions are simply bizarre, such as wǒde 我的 ("my") for "world".

- I suspect that Wu topolect phonology has led to some unexpected (from a MSM point of view) transcriptions, such as Qiānà 掐那 (lit., "pinch-that") for "China." See "The transcription of the name "China" in Chinese characters" (6/17/12).

I'm just getting started, but that should be enough to document the grounds for my dissatisfaction with this type of "spelling". It's no wonder that, when I first took a look at this booklet, I immediately exclaimed, "OMG!"

OMG is ubiquitous on the Chinese internet in the following forms (all parenthetical translations except #7 and #8 are literal syllable by syllable renderings):

- OMG — probably the most common form

- Ǒumǎigā 偶买咖 ("occasionally-buy-cur[ry]")

- Ǒumǎigāde 偶买咖的 ("occasionally-buy-cur[ry]-of"

) - Ǒumǎigá 偶买噶 ("occasionally-buy-syllable used for Tibetan transcriptions")

- Ómǎigá 哦买噶 ("oh-buy-syllable used for Tibetan transcriptions") — this form is very commonly encountered; both it and #4 rarely have a de 的 at the end for the final consonant of "God", as in #3

- Ómǎigāo 哦買糕 ("oh-buy-cake") — seems to be mainly a Taiwanese version

- Ó, wǒ de shàngdì 哦,我的上帝 ("Oh, my God")

- Tiān a 天啊 ("Heaven!")

Here are a few previous Language Log posts on this theme of "spelling" English with Chinese characters:

- "Spelling with Chinese character(istic)s" (11/21/13)

- "Spelling with Chinese character(istic)s, pt. 2" (6/16/16)

- "Sinographically transcribed English" (12/26/10)

- "Writing English with Chinese characters" (6/3/15)

- "'Spelling' English in Cantonese" (11/17/13)

Bottom line: Modern China has a perfectly workable, official system of romanization called Hànyǔ pīnyīn 汉语拼音 ("Sinitic Spelling"), with which all Chinese under the age of about 55 who have gone to school are familiar, so I don't see why there is any longer a need to go through the contortions demanded by this antiquated, clumsy, unsystematic method of transcribing foreign languages with Chinese characters.

[Thanks to Anne Henochowicz, David Moser, Kaiser Kuo, Matt Smith, and Kellen Parker]

John Swindle said,

July 1, 2016 @ 1:50 am

To hear what this stuff sounds like, copy the Chinese text and paste it into Google Translate. Tell Google Translate that you want to translate it from Chinese. Then click the "listen" link below the text. For some reason it works better to use the Chinese character text for this purpose than Pinyin. That is, the program does a better job of reading character text aloud than reading Pinyin aloud.

David Marjanović said,

July 1, 2016 @ 3:29 am

Note how the tones differ – did they mean to write down the intonation? A rising intonation on "West Lake," (note the comma) is correct; a falling one is at least not completely outlandish in "Moon over the Peaceful Lake in Autumn".

I'd have slapped in some kind of er (儿, 尔) into the middle, but other than that it's perfect. They chose the closest vowel they have available behind /w/. Tellingly, the e of de, te, ne, le would be very close phonetically, and that's probably the same phoneme as o.

Calvin said,

July 1, 2016 @ 9:38 am

In Taiwan, I've seen OMG as 歐買尬. It's apparently being used as part of the Taiwan title for the movie Dirty Grandpa (阿公歐買尬): https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%98%BF%E5%85%AC%E6%AD%90%E8%B2%B7%E5%B0%AC.

Oliver Radtke said,

July 3, 2016 @ 5:02 am

Victor,

the Global Times is doing an interview with me on this as I type. Let's see what the outcome is. I will keep you posted.

Best,

Oliver

Victor Mair said,

July 3, 2016 @ 8:24 am

Very good to hear from you again, Oliver. I'm looking forward eagerly to the results of your interview with Global Times.

Get ready for "Spelling with Chinese character(istic)s, pt. 4"!

Alyssa said,

July 4, 2016 @ 6:02 am

It's unclear to me exactly how many of these issues are truly issues with transcribing English via characters, and how many are simply poor transcription choices. Would this really be any better if they has written the same transcriptions in pinyin, as you've done here?

Victor Mair said,

July 5, 2016 @ 9:07 pm

"Wai-kan-mu tu Hangzhou: City’s sincere if cryptic messages of welcome to G20 foreign guests: Authorities use the sound of Chinese characters to approximate English pronunciation to teach residents a list of 100 handy phrases" (7/5/16)

…Such English instructional methods were common for Chinese pupils in the old days, especially in less-developed areas where the quality of education was questionable.

When the pamphlet was posted online, many internet users challenged the effectiveness of the method – with some even calling it a disgrace.

“Stupid method, it makes our countrymen lose face,” said one commentator.

Some residents complained that the government had already disturbed their daily lives far too much ahead of the G20 summit.

“I really can’t smile when I see [the words] G20. My workplace forces us to learn English at lunch break every day, and in the evening the TV broadcasts shows teaching English like this. The people of Hangzhou are tormented every day,” another wrote. [END]