"Spelling" English in Cantonese

« previous post | next post »

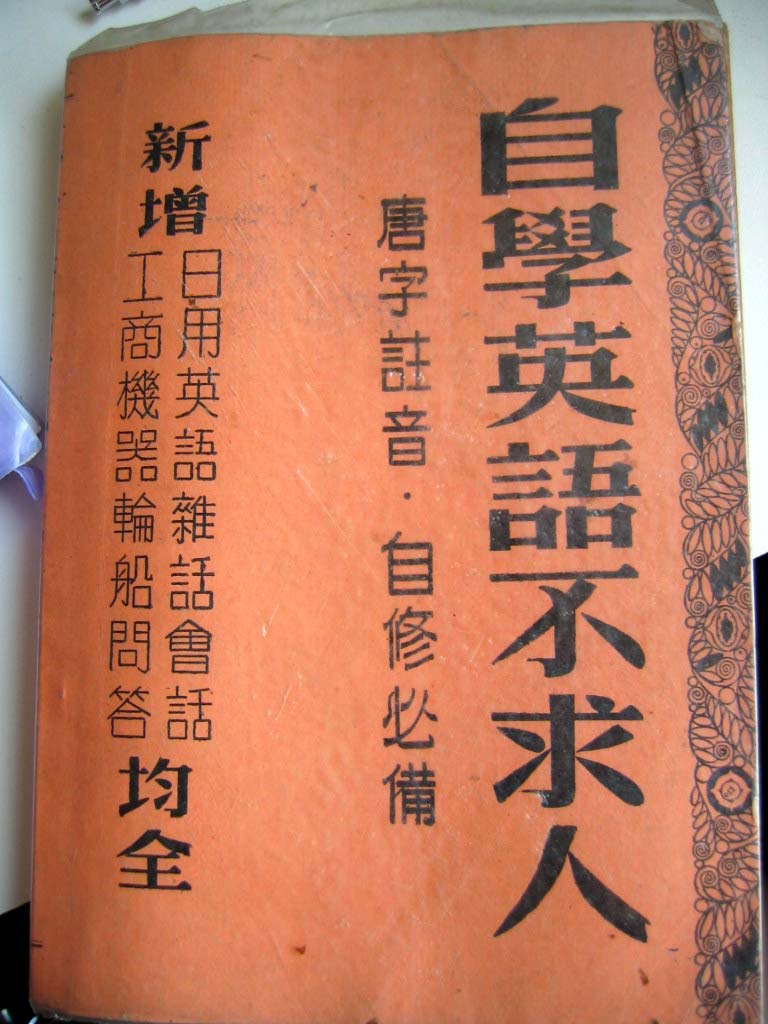

As a follow-up to my Language Log post on Li Yang's fēngkuáng liánxiǎng 疯狂联想 ("crazy association"), Chris Fraser sent me three images of an old Cantonese book that purports to teach English by means of what it calls "Táng zì zhù yīn" 唐字註音 ("phonetic annotation with Tang [i.e., Chinese] characters").

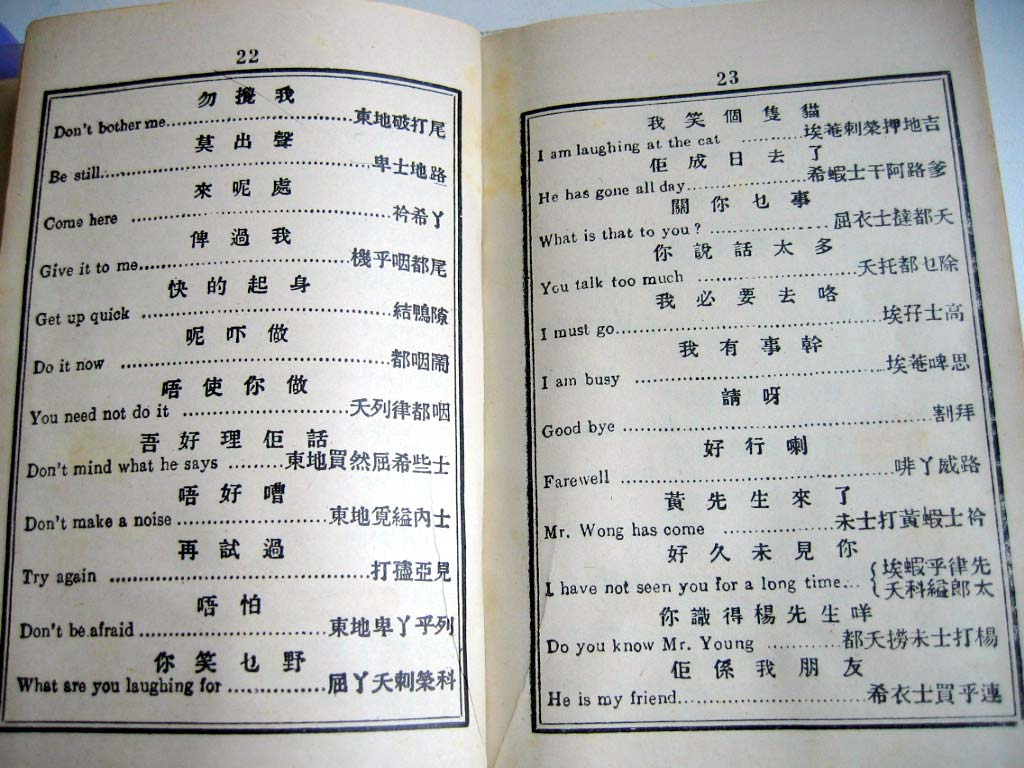

A few examples are transcribed and translated below.

Given the ca. 1902 date of the book, It's interesting how many of the Chinese translations are in Cantonese, not Mandarin (Guānhuà 官話 [lit., "officials' talk"]). The third one below is a good example. Clearly the book was aimed at the Hong Kong / Guangzhou regional audience.

p. 22, line 1:

"Don't bother me."

勿攪我 ("Don't disturb me.")

dung1 dei6 po3 daa1 mei5

東地破打尾

p. 22, line 2:

"Be still."

莫出聲 ("Don't emit a sound.")

bei1 si6 dei6 lou6

卑士地路

p. 22, line 8:

"Don't mind what he says."

吾[=唔]好理佢話 ("Don't attend to his speech.")

dung1 dei6 maai5 jin4 wat1 hei1 se1 si6

東地買然屈希些士

p. 23, line 3:

"What is that to you?"

關你乜事 ("What business is it of yours?")

wat1 ji1 si6 taat3 dou1 jiu1

屈衣士撻都夭

p. 23, line 10:

"I have not seen you for a long time."

好久未見你 ("For a long time I haven't seen you.")

aai1 haa1 fu1 leot6 sin1 jiu1 fo1 ai3 long4 taai3

埃蝦乎律先夭科縊郎太

The last one is a good early example of Cantonese "n" and "l" merger, as the writer must have pronounced 律 "leot6" as "neot."

[Thanks to Chris Fraser for calling this book to my attention and for help with the transcriptions]

Carl said,

November 17, 2013 @ 6:37 pm

I feel like I've seen something like this advertised on late night TV for English to Spanish. Does anyone else know what I'm talking about?

Carl said,

November 17, 2013 @ 6:41 pm

Here's one for English-Spanish, but not the one I was thinking of: http://books.google.com/books?id=blEwDv5Qi-UC&lpg=PR41&ots=GsB71uCSFi&pg=PR41#v=onepage&q&f=false

Matt said,

November 17, 2013 @ 8:05 pm

Is the usage of 唐字 instead of 漢字 a southern thing?

(And what's that character that looks like a "Y" and is apparently pronounced like an "a"?)

William Steed said,

November 17, 2013 @ 8:13 pm

Matt, that's 丫 (ya1 in standard Mandarin). It means 'fork (i.e. in the road)', or a pejorative word for 'girl'. See: http://www.mdbg.net/chindict/chindict.php?page=worddict&wdrst=0&wdqb=%E4%B8%AB

Fred said,

November 17, 2013 @ 8:28 pm

Matt,

You are correct, the usage of 唐字 is a southern thing, specifically, it's old Cantonese tradition. That's why China Town used to widely be called as "唐人街", since the earlier immigrants mostly speak Cantonese. Basically "唐人" means Chinese, which source from Tang Dynasty from 7-10th century.

Jake Nelson said,

November 17, 2013 @ 11:26 pm

I find it interesting how much clearer than usual the characters seem. I only know a few of them, but I find them much easier to distinguish in that printing style. Often I find it difficult in more modern printings (possibly because of size?), and handwritten (or otherwise nonstandard) is completely hopeless for me. Even without enlarging the image, these look great.

richardelguru said,

November 18, 2013 @ 7:14 am

The phonetic annotations are rather reminiscent of the old Mots D'Heures: Gousses, Rames

Stephan Stiller said,

November 18, 2013 @ 8:40 am

About sentence 5: I agree that it's evidence for the Cantonese [n]-[l] merger, but I would spell out the reason differently.

1. I would assume that 律 has always been leot6. Since n- merged into l-, it's possible that the author or intended speaker didn't have n- in his phonotactic inventory, and in that case even the English word "not" would have been pronounced as Cantonese jyutping "leot" (or perhaps jyutping "lot"). But I don't know how exactly the sound change progressed. (To what extent was there free variation between production of n- and l-, and how strong was the perceptual confusion? Were there "only-[n]" speakers?)

2. If one says that 律 was pronounced neot6 (instead of leot6) here in order to match the English word "not", that might simply be because of the lack of an appropriate frequent character pronounced jyutping "neot"/"not", not because of the [n]-[l] merger. That is, the reason for the author resorting to something with l- could simply have been the lack of common characters pronounced "neot". (Dictionaries give me 訥/neot6, and I think Cantonese doesn't have jyutping "not" at all. But 訥 is also naap6, so it wouldn't be suitable for unambiguously denoting the pronunciation jyutping "neot", and I don't know how common 訥-as-neot6 is anyways.) Still, this case would be evidence for the relative perceptual closeness of n- and l- for a Cantonese speaker.

(Btw: 乎 (sentence 5) is fu4; 呼 would be fu1. But in Mandarin, both are identical (hū), with a high level tone. 打 (sentence 1) is more commonly daa2, though both daa2 and daa1 are possible and plausible in a phonetic transcription context.)

In any case, the Cantonese transcriptions of English from that book are hilarious.

Daniel Tse said,

November 18, 2013 @ 9:06 am

The title of the book might actually be 自學英語不求人 zi6 hok6 jing1 jyu5 bat1 kau4 jan4 ('Learn English by yourself without asking (help from) others').

Lane said,

November 18, 2013 @ 10:08 am

I've often wondered why some nationalities seem to persist in heavy foreign accents when learning foreign-language-X than other nationalities do.

In the case of learning western languages like this, I can imagine it was impossibel to get anything like accent-free English. If there's an interfering system (like the Chinese character system) between the Roman letters of an English word and the speech-production-system of the learner, the mind is going to lean heavily on the helping system (the Chinese characters) at the expense of learning properly. If you're learning that "don't" is pronounced "dung1", you're never going to get even close.

Similarly, I wonder if the use of katakana for English words in Japanese doesn't make it hard for Japanese learners to put aside Japanese phonology and phonotactics and learn how to pronounce English words as English words.

The same can of course be said the other way round; many English learners of Mandarin probably have accents that are influenced by the romanization system they learned with. I've heard (maybe here) that you can even tell a "Pinyin accent" from a "Wade-Giles accent"…

All the better reason to put aside such helpers as soon as is practical…

JQ said,

November 18, 2013 @ 1:48 pm

If 律 was pronounced neot6, surely the Mandarin reading would be nv4 rather than lv4

The suffocated said,

November 18, 2013 @ 4:25 pm

This kind of phonetic annotations are still preserved in Chinese almanacs published in Hong Kong, but more as a nostalgic tradition than as a serious pedagogical attempt. Also, when Google redirected queries from google.cn to google.hk three years ago (in response to internet censorship in mainland China), names on the simplified Chinese version of Google Map had been mistakenly rendered as transliterations in Mandarin for a while. For instance, "Department of Management and Marketing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University" was shown on the map as "迪帕特门特奥夫马尼季门特&马基廷,瑟亨康波利泰克尼克大学" for a few months. That gave the Kongees quite some laughs back then.

By the way, for "not", I think 諾 is a better choice than 律.

Stephan Stiller said,

November 18, 2013 @ 6:20 pm

@ JQ

That's the instinctive reasoning, and then there are resources to check (which don't give evidence for n-). Interestingly one will find a discrepancy for 粒, which is lì in Mandarin but prescriptively nap1 in Cantonese. Nowadays it's always lap1, though, and it's entirely possible that it's been lap1 for a long time.

@ The suffocated

… because 諾 is nok6, and Cantonese -k is glottalized to varying degrees.

Victor Mair said,

November 18, 2013 @ 11:43 pm

From Bob Bauer:

=====

Regarding spelling English words with Chinese characters pronounced in Cantonese:

For what it's worth, according to Cantonese dictionaries with romanization produced back in the 19th and early 20th centuries, diphthong "ei" was pronounced "i" in those days, so the characters 尾 mei5, 卑 bei1, and 希 hei1 in your examples would actually have been pronounced mi5, bi1, and hi1, respectively, which is very close to the pronunciations of English words "me", "be", and "he". For more details, please see the attached PDF article.

=====

VHM: Bob is referring to the 2nd article here:

Hong Kong Journal of Asian Linguistics, 10.1 (2005), though other articles will undoubtedly be of interest to some readers of this post and its comments. The links will probably be lost, but can easily be retrieved by going to the HKJAL website.

Chinese Transcription of Foreign Words prior to the 19th Century

Geoff Wade

HKJAL / Volume 10 / Issue no. 1, pp. 1 – 20

Abstract | Full text [PDF]

Two 19th Century Missionaries’ Contributions to Historical Cantonese Phonology

Robert Bauer

HKJAL / Volume 10 / Issue no. 1, pp. 21 – 46

Abstract | Full text [PDF]

Chitqua’s English Adventure: An Eighteenth Century Source for the Study of China Coast Pidgin and Early Chinese Use of English

David Clarke

HKJAL / Volume 10 / Issue no. 1, pp. 47 – 58

Abstract | Full text [PDF]

The Origins of Chinese Pidgin English: Evidence from Colin Campell’s Diary

Phil Benson

HKJAL / Volume 10 / Issue no. 1, pp. 59 – 78

Abstract | Full text [PDF]

Pidgin English Texts from the Chinese English Instructor

Michelle Li, Stephen Matthews and Geoff P. Smith

HKJAL / Volume 10 / Issue no. 1, pp. 79 – 168

Abstract | Full text [PDF]

Stereotyped Chinese Pidgin English as an Interlude in Linguistic Sources: Three Early 20th Century Instances

Anthony P. Grant

HKJAL / Volume 10 / Issue no. 1, pp. 169 – 176

Abstract | Full text [PDF]

Simon P said,

November 19, 2013 @ 2:54 am

Late to the party, but a few comments on the n/l thing, in case anyonw is still reading this:

1: Sometimes, like Stephan Siller says, the Cantonese prescriptive n/l initial doesn't match the Mandarin. In the case of 粒 I believe it's a hypercorrection, but with 弄, it's "lung6" in Cantonese and "nong4" in Mandarin, and here it seems it's Mandarin that changed the initial.

2: The 律 thing might be a case of hypercorrection. It's not unusual for people who try to keep the n/l distinction to make mistakes and pronounce words that ought to have an 'l' with an 'l' instead.

Anthony said,

November 19, 2013 @ 2:16 pm

Look! A new (old?) way to give Americans bad Chinese-character tattoos!

Matt said,

November 19, 2013 @ 8:17 pm

The HKJAL website doesn't seem to allow the general public to actually download the articles. I don't suppose there's any other way to see them?

(And thanks, William and Fred!)

Hilário de Sousa said,

November 21, 2013 @ 8:16 am

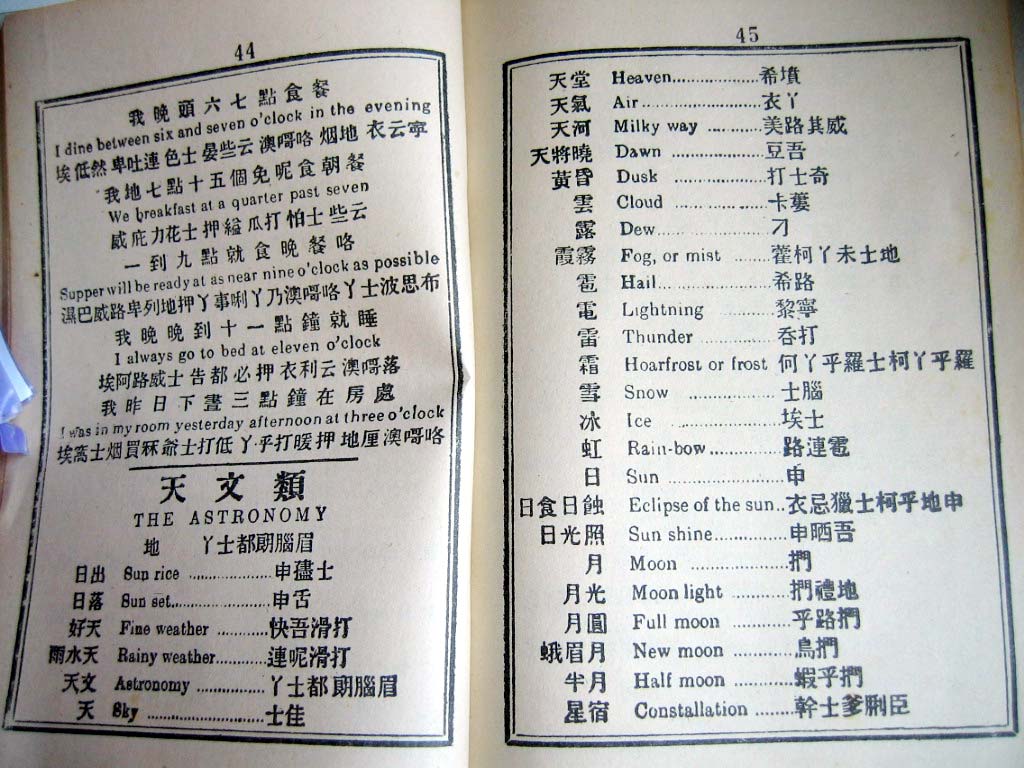

So I found that this book was published in Hong Kong. I doubt that many Hong Kongers of that age would have merged the n/l onsets. Just looking at the two images of bilingual texts that you posted, I would say that the author had a clear n/l onset distinction in both English and Cantonese:

(All cases of English n/l onsets, and cases of English n/l codas represented by a separate Chinese character with n/l onset in Cantonese:)

'Correct' cases:

still 士地路 si6dei6lou6

now 鬧 naau6

noise 內士 noi6si6

laughing 剌榮 laa1wing4

Farewell 啡丫威路 fe1(ng)aa1wai1lou6

long 郎 long4

evening 衣云寧 ji1wan4ning4

afternoon 丫乎打暖 (ng)aa1fu4daa2nyun5

astronomy 丫士都朗腦眉 (ng)aa1si6dou1long5nou5mei4

rainy 連呢 lin4ni1

lightning 黎寧 lai4ning4

snow 士腦 si6nou5

light 禮地 lai5dei6

constalation 幹士爹脷臣 gon3si6de1lei6san4

'Wrong' cases:

need 列 lit6

not 律 leot6

Unclear, perhaps incorrect:

near 唎丫 li1(?)aa1

Perhaps this is just a case of using other similar sounding characters to represent the syllables /nit/ and /not/ (or /lot/) which do not exist in Cantonese.

Nonetheless, the last case of near 唎丫 may or may not be an indication of an n/l merger happening; it is difficult to argue that 唎 necessarily had an l onset, and not an n onset.

Hilário de Sousa said,

November 21, 2013 @ 8:29 am

I would say that referring to China- as 唐- is moribund in Pearl River Delta; it is mainly restricted to fossilised expressions like 唐人街 'Chinatown'.

I've heard of Cantonese being referred to as 唐話 twice in my life. Once was in Auckland. I went into a 'prehistoric' Chinese takeaway, and started talking to them in Cantonese by default. The owner, who perhaps was not used to serving Cantonese-speaking customers, replied: 'Oh, you know how to speak 唐話'. I later found out that they left Macau more than forty years ago.

Another time was in Sydney. I was at a Vietnamese food stall, and I switched from English to Cantonese once I heard the old lady switching from Vietnamese to Cantonese when talking to other people. The old lady said to me: 'You should have spoken to me in 唐話 right from the start!'

Stephan Stiller said,

November 22, 2013 @ 1:49 am

@ Simon P

You mean "words that ought to have an 'l' with an 'n' instead". In principle that's a possibility, but the book was written so long ago that I'm assuming hypercorrection wasn't an issue then.

@ Hilário de Sousa

Thanks, that's very informative! I would conclude that the "wrong" cases you list are evidence for perceptual closeness, which is – while not by itself evidence for the [n]-[l] merger – consistent with it.

hanmeng said,

November 24, 2013 @ 9:36 pm

@ Lane,

In Taiwan many people used to insist that using Bopomofo (Zhuyin fuhao) was the way to ensure that foreign learners of Mandarin wouldn't be misled by their own alphabet. On the other hand, others promoted Y.R. Chao's Gwoyeu Romatzyh to ensure than students would master the tones in Mandarin. Neither seems to have enjoyed much widespread success.