Chinese, Japanese, and Russian signs at Klagenfurt Botanical Gardens

« previous post | next post »

Blake Shedd sent along a series of forty pictures of plant identification signs from the botanical garden in the small southern Austrian city of Klagenfurt am Wörthersee. He was rather impressed that the botanical garden staff went to the trouble of including non-Latin / non-German names for the plants. And I was impressed at the remarkable documentation Blake provided by carefully and clearly photographing so many signs with essentially the same lighting and size. There's no need for him to apologize ("leaning over roped-off areas to get shots resulted in a few blurry or less than ideal shots"). The green leaves appearing at the edges of some of the photographs, which are otherwise black and white, only serve to enhance the arboreal, herbaceous atmosphere evoked by reading the signs.

One thing that struck Blake about the Chinese names was that some of the characters are printed sideways (turned ninety degrees counterclockwise, e.g., Trachelospermum jasminoides ["confederate jasmine", "star jasmine", "confederate jessamine", "Chinese star jessamine"]). Blake also noticed that the tones are not marked on the pinyin, though I think they deserve a lot of credit for putting up characters and romanization at all.

Nearly all of the Japanese katakana are in the correct orientation, but on the Iris japonica ( "fringed iris", "shaga", "butterfly flower") sign they are rotated as well; additionally, no transliteration is provided for the katakana.

The name for Syringa reticulata ("Japanese tree lilac") is given in Chinese even though the plant is listed as coming from Japan (the Japanese name would be hashidoi ハシドイ). The difficulty in choosing among Chinese, Japanese, and Russian here is that this plant is native to a wide swath of eastern Asia: northern Japan (mainly Hokkaidō), northern China (Gansu, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Henan, Jilin, Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Sichuan), Korea, and far southeastern Russia (Primorye). The same is true to one degree or another for many of the other plants. For Carex mollicula, no non-Roman characters are printed, though a Chinese name is given here that doesn't match the romanization printed on the sign: "Hima-shira-suge". Shirasuge (白菅, usually written in kana, しらす げ / シラスゲ) is a kind of carex, viz., Carex alopecuroides var. chlorostachya (a species of sedge). I don't know what "Hima-shira-suge" is.

Blake had a question that relates to the system of providing Chinese (or Japanese, Russian, etc.) names for the plants:

I assume these names are the common names; that said, are Latin names then translated / transliterated into Chinese (et al.) or are they normally printed in Roman characters in journals/signs? My last question was whether the Chinese names represent the most common name or are these regional variants that reflect the origin of the plant in China.

Short answers in quick succession:

1. Yes, the Chinese and Japanese names are the common ones.

2. No, the Latin names are not translated / transcribed into Chinese, et al. — they are normally printed in Roman letters in journals, on signs, and so forth.

3. The Chinese name is normally the most common MSM name, regardless of what part of China the plant may have originated from and where they may have quite different names.

And now a query of my own. All the labels that Blake meticulously photographed consist of the Latinate scientific names, with Chinese, Japanese, and Russian common names. I was struck by the fact that not all of the plants have common German names, but when they do, the names seem to be on the long side — perhaps that's just the nature of the German language.

I asked Blake if they gave English translations anywhere. Here's his reply:

English translations only seem to be included if the plant is native in an English-speaking country (like the scouringrush horsetail sign for a North American native). I don't remember (m)any other signs including English, but I was also focusing on signs with non-Roman scripts. The next time I'm there, I'll have a look, but I don't recall seeing English names for plants that aren't native in English-speaking areas.

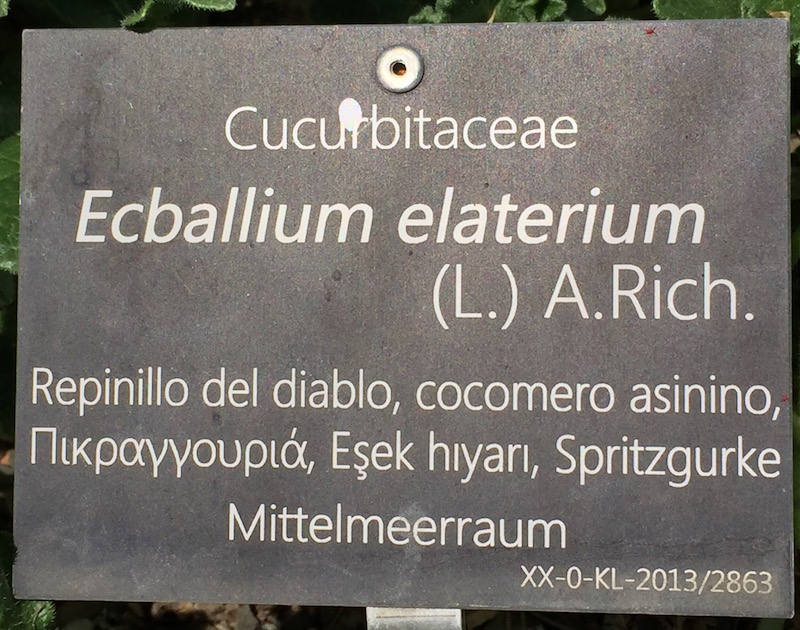

There are a few examples like the photo below with non-Roman scripts*, but I didn't take many pictures of them. Given that the Mediterranean is the common region for these plants, the languages included isn't surprising (though I am surprised that the dotless-i "ı" and "ş" of Turkish are correctly rendered.

[*VHM: also not Chinese, Japan, or Russian]

Another section (seemingly for well-known medicinal and culinary herbs) includes Braille (!). Here's one example of these signs (only the Latin and German names are included):

According to the German Wikipedia page on Braille, the sign above reads (I don't know if majuscule/minuscule forms exist in Braille):

YSOP

HYSSOPUS

OFFICINALIS

As for the German names, I agree they do seem to be long; I'm slowly working on learning these names and the many dialect variations for them. That's a long term goal at any rate.

Since we've been talking about the Latin scientific names for various plants, I'd like to add a final note about the Linnaean classification of tea, namely, it has by no means been engraved in stone since the system was first devised.

From the Wikipedia article on tea:

The name Camellia is taken from the Latinized name of Rev. Georg Kamel,[3] SJ (1661–1706), a Moravian-born Jesuit lay brother, pharmacist, and missionary to the Philippines.

Carl Linnaeus chose his name in 1753 for the genus to honor Kamel's contributions to botany (although Kamel did not discover or name this plant, or any Camellia, and Linnaeus did not consider this plant a Camellia but a Thea).

Robert Sweet shifted all formerly Thea species to the Camellia genus in 1818. The name sinensis means from China in Latin.

"Thea" here refers to "tea", which is derived from the Minnan (Sinitic) word for the plant. See Appendix C of Victor H. Mair and Erling Hoh, The True History of Tea, for a detailed discussion of the graphic derivation, historical phonology, and semantic evolution of the Sinitic character and word for "tea".

MSM chá 茶; Cantonese caa4; Hakka (Pha̍k-fa-sṳ) chhà; Min Dong (BUC) dà; Min Nan Hokkien, POJ tê, Teochew, Peng'im dê5; Wu (Wiktionary) zo

Middle Sinitic Reconstructions (ca. 600 AD):

| Zhengzhang Shangfang |

Bernard Karlgren |

Li Rong |

Pan Wuyun |

Edwin Pulleyblank |

Wang Li |

Shao Rongfen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ɖɣa/ | /ȡʱa/ | /ȡa/ | /ɖɯa/ | /ɖaɨ/ | /ȡa/ | /ȡa/ |

Old Sinitic (ca. 600 BC): /*rlaː/ (Zhengzhang system)

Cf. Proto-Sino-Tibetan *s-la < archaic Austro-Asiatic *la ("leaf").

Cognate with tú 荼 (“bitter plant”).

For the etymology of tea, see here.

Although in recent times there has been a working consensus on calling the plant Camellia sinensis or, to drive home the point even more forcefully, Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, with Indian Assam teas being subsumed under the Chinese variant as Camellia sinensis var. assamica. Botanically and genetically, however, that is not a foregone conclusion, since the plant's natural homeland ranges from Assam through northern Burma to the southernmost part of what is now Yunnan and northern Laos.

In any event, judging from this long list of scientific synonyms for the plant, it is evident that there has never been unanimity of opinion on what to call the tea plant in Latin.

- C. angustifolia Hung T. Chang

- C. arborescens Hung T. Chang & F. L. Yu

- C. assamica (J. W. Masters) Hung T. Chang

- C. dehungensis Hung T. Chang & B. H. Chen

- C. dishiensis F. C. Zhang et al.

- C. longlingensis F. C. Zhang et al.

- C. multisepala Hung T. Chang & Y. J. Tang

- C. oleosa (Loureiro) Rehder

- C. parvisepala Hung T. Chang.

- C. parvisepaloides Hung T. Chang & H. S. Wang.

- C. polyneura Hung T. Chang &

- C. thea Link

- C. theifera Griffith

- C. waldeniae S. Y. Hu

- Thea assamica J. W. Masters

- Thea bohea L.

- Thea cantonensis Loureiro

- Thea chinensis Sims

- Thea cochinchinensis Loureiro

- Thea grandifolia Salisbury

- Thea olearia Loureiro ex Gomes

- Thea oleosa Loureiro

- Thea parvifolia Salisbury (1796), not Hayata (1913)

- Thea sinensis L.

- Thea viridis L.

- Theaphylla cantonensis (Loureiro) Rafinesque

Laura Morland said,

June 12, 2016 @ 11:43 am

Thanks for this interesting post, Victor Mair!

I'd love a follow up: perhaps Blake Shedd would be interested in interviewing the director of the Klagenfurt am Wörthersee garden and ask him (or her) not only about the decision to include the native names of all the plants, but also the difficulties in (1) deciding which native name(s) to include, (2) selecting the text, and (3) finding a local engraver capable of rending non-Latin alphabets.

Rodger C said,

June 12, 2016 @ 12:06 pm

I am surprised that the dotless-i "ı" and "ş" of Turkish are correctly rendered

I suppose there are enough Turkish-speakers in Austria to ensure this.

Bathrobe said,

June 12, 2016 @ 5:02 pm

That should be Hime-shira-suge (ヒメシラスゲ, 姫白菅). See ヒメシラスゲ. 姫 hime 'princess' is commonly used for smaller species in a genus.

Jack Williams said,

June 12, 2016 @ 5:02 pm

I guess the names were copied and pasted from Wikipedia or somewhere and simply printed onto the signs – the sign printer attached to a computer. No need for advanced knowledge of Chinese, Turkish, Russian, or their scripts.

John Swindle said,

June 13, 2016 @ 1:21 am

Braille has a marker for capital letters rather than a separate alphabet of capital letters. Used twice in succession, it marks block capitals. It's not used here, nor is it really needed.

Hans Adler said,

June 13, 2016 @ 11:11 am

As a German I don't find anything strange or unusually long about the German plant names – for the context of a botanical garden, that is. They are not common names in the strictest sense. Instead, they contain determiners that define the species almost as well as the Latin name does. (Also sometimes two German names are separated by commas.)

– Pyrus ussuriensis = Ussuri-Birne, Mandschurische Birne = Ussurian pear, Harbin pear, Manchurian pear.

– Cerasus nipponica = Japanische Kirsche = Japanese alpine cherry.

– Trachelospermum jasminoides = Sternjasmin = [Chinese] star jasmine/jessamine.

– Armeniaca mandshurica = Mandschurische Aprikose = Manchurian apricot, Scout apricot.

– Arnica sachalinensis = Sachalin-Arnika = (Sakhalin arnica).

– Allium flavescens = Gelblich-Lauch = (Yellowy leek).

– Primula denticulata = Kugel-Primel = drumstick primrose.

– Viola altaica = Altai-Stiefmütterchen = Altai pansy.

– Metasequoia glyptostroboides = Urweltmammutbaum = dawn redwood.

– Cephalotaxus harringtonii = Harrington-Kopfeibe = Japanese plum-yew, cowtail pine

– Equisetum hyemale = Riesen-Winter-Schachtelhalm = rough horsetail, scouring rush [horsetail].

– Syringa pubescens subspecies microphylla = Kleinblättrig-Flieder = Littleleaf lilac.

In two cases I could not find an English common name and supplied my own translation in parentheses. Stiefmütterchen, lit. little stepmother, is a genus of viola characterised by the garden pansy as its most prominent member. This quaint name is in fact a bit longer than the equivalent English name. I think this is probably one of the successful coinages from the Romantic era, when German poets tried to replace Romance words with Germanic ones. The word Urweltmammutbaum consists of four parts and translates literally to primeval world mammoth tree. Kopfeibe translates to head yew. Riesen-Winter-Schachtelhalm translates to giant winter horsetail, where Schachtelhalm (horsetail) literally means nesting stalk.

This indiscriminate list of German names appearing from the top (continued up to the point where I got bored) seems typical for all the names. Where the German names are longer than the English ones, its typically because some component is more descriptive than just copying the Latin name. E.g. German for coriaria is Gerberstrauch (tanner's bush). Also the use of sch/ch/dsch/tsch rather than sh/j in geographic names tends to make these longer, and of course German compound words generally look more impressive than English ones as they are spelled as one word or with hyphens.

FM said,

June 13, 2016 @ 11:13 am

The plant romanized as Sembon-Yari is given in katakana as センボニャリ, i.e. se.n.bo.nya.ri, rather than センボンヤリ se.n.bo.n.ya.ri. I wonder how such an error could have happened — it seems like during the process, someone who didn't know any Japanese must have been converting a romanization back to katakana…

Michael G said,

June 13, 2016 @ 12:21 pm

Whatever their sins or virtues other languages, the sign makers could brush up on their Spanish: "repinillo" should be "pepinillo," the diminuitive of "pepino," or cucumber. Hence "the devil's pickle" or "devil's little cucumber" in reference to its shape, size, and toxicity. An odd typo to make, considering the distance between the letters P and R on the keyboard.

Bathrobe said,

June 13, 2016 @ 4:37 pm

@Hans Adler

they contain determiners that define the species almost as well as the Latin name does

What are known as "common names" in biology are not necessarily common at all. The implications of "common" seem to have changed from "in ordinary use" to "used in common". They are, in effect, "vernacular scientific names". The original impetus may have been to give familiar names from the vernacular, but it wasn't long before the assignment of correct, standardised, scientifically-valid vernacular names became the objective.

I didn't feel that the German was overly long. Perhaps the problem is the custom of running nouns together in the orthography, which looks forbidding to English speakers who are used to writing them as separate words.

Michael Conner said,

June 18, 2016 @ 6:17 am

The first image in this post includes Greek, not Russian.