Four centuries of peeving

« previous post | next post »

Several readers have recommended Wednesday's Non Sequitur:

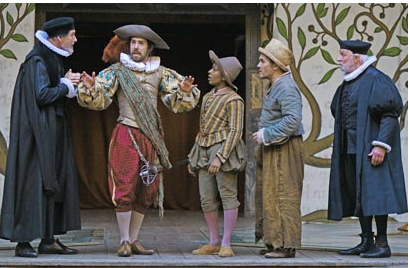

Also on Wednesday, I saw the wonderful Shakespeare's Globe production of Love's Labour's Lost. Paul Ready was especially hilarious as Don Adriano de Armado, to single out one great performance among many. Christopher Godwin's portrayal of Holofernes the pedant was another.

Also on Wednesday, I saw the wonderful Shakespeare's Globe production of Love's Labour's Lost. Paul Ready was especially hilarious as Don Adriano de Armado, to single out one great performance among many. Christopher Godwin's portrayal of Holofernes the pedant was another.

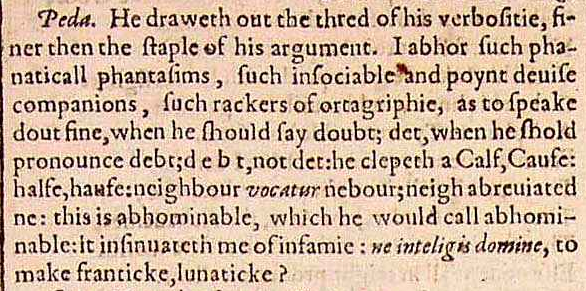

I had forgotten the passage where Holofernes complains about Armado's pronunciations. The complaint is not about Armado's Spanish accent, but about his unetymological pronunciations — omitting the 'b' in doubt and debt, and the 'l' in half and calf; leaving out the reflex of 'gh' in neighbor and neigh; inserting (or removing?) [h] in abominable:

He draweth out the thred of his verbositie, finer then the staple of his argument. I abhor such phanaticall phantasims, such insociable and poynt deuise companions, such rackers of ortagriphie, as to speake dout fine, when he should say doubt; det, when he shold pronounce debt; d e b t, not det: he clepeth a Calf, Caufe: halfe, haufe: neighbour vocatur nebour; neigh abreuiated ne: this is abhominable, which he would call abhominable: it insinuateth me of infamie: ne inteligis domine , to make franticke, lunaticke?

The text fails to make it clear whether the alleged flaw is adding or lacking an [h] in abominable, since both Holofernes' own pronunciation and his presentation of Armado's pronunciation are spelled "abhominable" in the text — the version above is from the 1623 First Folio, but the 1598 Quarto is the same in that respect. The issue, according to the OED, is a sort of Renaissance eggcorn:

Forms with medial -h- in post-classical Latin, Middle French, and English arose by a folk etymology < classical Latin ab homine away from man, inhuman, a derivation which has also influenced the semantic development of the word in English and French. Forms with -h- were common in English until the 17th cent., when they began to be criticized by orthographers.

It strikes me that it would be funnier to have Holofernes' correction in this case be an incorrection — but now I can't remember for sure how Godwin performed it.

In any case, this passage is the earliest example of linguistic peeving that I can think of. Can anyone give me an example before 1598?

I dimly recall that there might be something of the sort in Plautus, but I think it involves making fun of a rustic accent, rather than complaining about forms that reflect an on-going change in the language. I can't find the passage, anyhow.

[As the many helpful examples in the comments make clear, this is far from the earliest example of linguistic peeving. But so far, it does seem to be the earliest example in which (as is so often the case) all or nearly all of the corrections are incorrect.]

[For some interesting discussion of spellings (and characters, events, and themes) in Love's Labour Lost, see this essay by Eric Sams.]

[Update — the version of the passage above, which I got by cut-and-paste from (I think) this version of the 1623 First Folio, has abhominable in both places, as indicated in this fascimile:

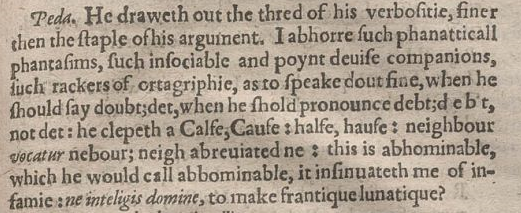

But the 1598 Quarto clearly has abhominable … abbominable:

Peter Taylor said,

October 30, 2009 @ 7:26 am

Athenaeus' Ulpian?

Joseph Howley said,

October 30, 2009 @ 8:19 am

What about Varro in "De Re Rustica" 1.2.1: "On the festival of the Sementivae I had gone to the temple of Tellus at the invitation of the_ aeditumus_, as we have been taught by our fathers to call him, or of the _aedituus_, as we are being set right on the word by our modern purists." ( http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Varro/de_Re_Rustica/1*.html#2 )

Sounds like rival peeving. Aulus Gellius picks it up two centuries later in Noctes Atticae 12.10: "_Aeditumus_ is a Latin word and an old one at that, formed in the same way as _finitimus_ and _legitimus_. In place of it many to-day say _aedituus_ by a new and false usage, as if it were derived from guarding the temples." (etc) ( http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Gellius/12*.html#10 )

(loeb translations all)

He's got some more peeving of his own at Noctes 6.11 ( http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Gellius/6*.html#11 ), and several other places.

Adrian said,

October 30, 2009 @ 8:33 am

Love's Labour's Lost

Orion said,

October 30, 2009 @ 9:05 am

There's good old Catullus 84, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0005%3Apoem%3D84 , which is also not so much about ongoing change in the language, as about mocking an affectation of hellenized elegance.

Cameron said,

October 30, 2009 @ 9:12 am

Tangential point here: did anyone ever conclusively prove or disprove Anthony Burgess's conjecture that the word "Holofernes" was used as a slang term for the penis in Elizabethan times.

language hat said,

October 30, 2009 @ 9:35 am

Catullus 84:

Lucy said,

October 30, 2009 @ 9:38 am

Well, of course there's Catullus Carmen 84 ("Chommoda he said, when commoda he wished to say and hinsidious aired Arrius instead of insidious;"), but that's very much a rustic accent peeve.

Oddly enough, someone else brought it up in the context of Love's Labour's Lost and Armado; the text I found first with Google came from http://www.questia.com/googleScholar.qst;jsessionid=KqqPwtvLxyg1t2qQGvLqYMxNTyv6lT7QbnjYGhQQgxf1p3wyGJfM!1275526282!-1845046985?docId=96232414 (A Note on Wit'Olding and Aspirating in Love's Labours Lost).

language hat said,

October 30, 2009 @ 9:44 am

From Aristophanes and the definition of comedy, by M. S. Silk (page 99):

(Emphasis added.)

James Enge said,

October 30, 2009 @ 10:02 am

Why did I know this thread would be full of comments from Latinists? On the subject of ancient purists, I immediately thought of Seneca (_Epistulae_ 39.1) where he complains in passing that what is "now" (mid-60s AD) called a _breviarium_ used to be called a _summarium_ in the days "when we spoke Latin" (cum latine loqueremur). He has a big thing about how your style equates with your moral identity, too–that's letter 115, I think.

There's a story of the Emperor Vespasian being dogged by a pronunciation purist, too. Vespasian had the vulgar habit of pronouncing the diphthong _au_ as a long _o_. So one day a guy name Florus bugged him about it, telling him to say _plaustra_, not _plostra_. So the next day Vespasian greets him as "Flaurus". This is almost certainly one of the funniest things to be found in the 22nd chapter of Suetonius' _Vita Vespasiani_.

JE

John Cowan said,

October 30, 2009 @ 10:29 am

In the edited text that I read, the second token of abominable is spelled "abbominable", presumably on the assumption that all of Holofernes' cases are incorrections. Certainly debt and doubt have never had /b/ in English (nor in French either) and the presence of orthographic "b" in the English spellings is pure Latinizing pedantry. The /l/ in calf, half was probably, and the /x/ in neighbour certainly, gone from London English in Shakespeare's time.

In short, this is not peevery about ongoing changes in the language: it is peevery that wants to pronounce every word exactly as spelled, and therefore reflects changes that are either long over or outright imaginary.

Doug said,

October 30, 2009 @ 10:34 am

"The Appendix Probi Appendix of Probus, compiled in 3rd-4th centuries AD, lists correct and incorrect forms of 227 words."

http://www.orbilat.com/Languages/Latin_Vulgar/Vocabulary/Appendix_Probi.html

Jed said,

October 30, 2009 @ 10:58 am

Wikipedia gives an example of someone from the 2nd century AD whining about those darn kids speaking that horrible Koine nonsense instead of proper Attic Greek: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koine_Greek#Sources

Aaron Davies said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:30 am

This isn't at all an ante-dating, but I'm reminded of the great scene in Molière's Le Bourgeois gentilhomme where a tutor attempts to instruct Monsieur Jourdain in how to speak with a proper upper-class Parisian accent.

Aven said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:32 am

Theocritus Idyll 15 (http://www.blackcatpoems.com/t/the_two_ladies_of_syracuse.html ; forgive the unscholarly link, it was the first I found) has a passerby comment disparagingly on the "cooing" of the speakers, who are Doric; the implication is that their pronunciation is unpleasant or wrong. That's 3rd cent. BC.

Andrew said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:33 am

אין מורידין לפני התיבה לא אנשי בית שאן ולא אנשי בית חיפה ולא אנשי טבעונין מפני שקורין לאלפין עיינין ולעיינין אלפין

"Neither men from Bet-She'an nor men from Haifa may descend before the ark [to lead the community in prayers] because they pronounce their alephs like 'ayins and their 'ayins like alephs."

Babylonian Talmud, Volume "Megillah", page 24b.

Aaron Davies said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:36 am

Oh, can we count "shibboleth" as peeving? The minor Israelite civil war it comes from was c. 1200 B.C.

I'm sure there's something in Sumerian about these kids today and their degenerate slang…

Mark P said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:41 am

John Cowan answered a question I had, namely whether the "b" was ever pronounced in words like debt. I understood that to be the case when I read the passage, but then I started thinking (always risky, of course) and wondered whether I could have been mistaken.

Dave said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:42 am

Was "than" spelled like "then" in Shakespeare's day? I realize that spelling was more variable than it is today, but it still looks odd to my eye.

Aaron Davies said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:46 am

@Aven: Attics (Athenians) considered Dorics (Spartans) to be hopeless rubes; this was amusing borrowed (probably by some bored Oxonians) to refer to Lowland Scots.

@Andrew: o the irony, given that most modern Hebrew speakers pronounce them identically as well—not at all.

James Enge said,

October 30, 2009 @ 12:00 pm

About whether the "b" in "debt" was ever pronounced: the tyrant OED says that the word was already "dete"/"dette" in Old French, and that's how it often appears in ME. So, if I had to bet on it, I'd bet that it was loaned into English without a "b", and that the "b" snuck back into the spelling through law Latin or something.

Andrew said,

October 30, 2009 @ 12:26 pm

@Aaron: I don't think it's ironic at all — these were the Babylonian Jews complaining — sorry, kvetching — about the "Western" Jews (Bet Shean and Haifa being in the Land of Israel).

marie-lucie said,

October 30, 2009 @ 12:52 pm

With the rediscovery of the classics and the spread of Latin as a learned language outside of the Church or the law, Latin "etymological" letters were reintroduced in the spelling of French and English words, apparently independently. Old and Middle French had a very "phonetic" spelling, but Rabelais, for instance, uses a lot of extra letters, as in "dict" for "dit" ('says, said' for instance. Many of these extra letters were later removed. Similarly, in English the "b"s of the Latin ancestral forms were reintroduced into words already borrowed from French such as "dette" and "doute", and are still written in the English words "debt" and"doubt". No doubt Holofernes' pronunciation of the added letters was a pedantic affectation which never became common in the speech of the majority.

Spell Me Jeff said,

October 30, 2009 @ 12:57 pm

@James Enge

I ran to my Loeb edition (one of the few I own) and found, to my amusement, that Epistle 115 opens with an exhortation not to be concerned with matters of style, eg: "Whenever you notice a style that is too careful and too polished, you may be sure that the mind also is no less absorbed in petty things." and "Elaborate elegance is not a manly garb."

It is not exactly a warning against prescriptivism, but I think one could interpret it thus.

Then again, Seneca's epistles are full of inconsistencies.

Has anyone plumbed Montaigne on this matter?

Jonathan Cohen said,

October 30, 2009 @ 1:08 pm

Spot on, Hat. I was thinking of exactly this — the scene from Aristophanes' Lysistrata with the Megarian, who speaks in thick and practically unintelligible Doric. One of Aristophanes's translators — Arrowsmith, I think — represents this in English with a syrupy Southern drawl.

Ian B said,

October 30, 2009 @ 1:11 pm

From Victor Bers, "Genos Dikanikon":

"But there is also some anecdotal evidence that the Athenians could be fastidious in matters of morphology or pitch accent. If we can believe the scholiasts' account of Demosthenes' deliberate mispronounciation of the word he claimed applied to Aeschines, μισθωτός ('lackey working for hire'), as a proparoxytone [ie, μίσθωτος], even those Athenians present who favored Aeschines, simply because they could not tolerate an accent wrongly placed, were tricked into shouting out a correction, making it appear that virtually everyone accepted Demosthenes' characterization of his opponent."

David Marjanović said,

October 30, 2009 @ 2:29 pm

LOL! I can imagine the crowds, fist in the air, shouting rhythmically "Μισ-θω-τός! Μισ-θω-τός! Μισ-θω-τός!" :-D :-D :-D

Evil.

Andrew (not the same one) said,

October 30, 2009 @ 3:19 pm

Jonathan Cohen: Is the Megarian passage really peevish, though? I don't think Aristophanes is suggesting that the Megarian is wrong to talk like that; it's just that the way outsiders talk is considered funny.

(In translations I'm familiar with, Doric is represented by Scots. This is particularly appropriate, since one dialect of Scots is actually called Doric.)

Harry Campbell said,

October 30, 2009 @ 3:33 pm

This reminds me of Alan Bennett’s story of the time Margaret Thatcher visited All Souls College Oxford (where she was so hated they denied her the customary honorary degree for Prime Ministers who had studied at Oxford). The don charged with showing her round toyed with the idea of pointing out the portrait of GDH Cole with the words “And this is the philosopher G.D.H. Dole,” in the hope she might correct him “Cole, not Dole”. (For those who don’t know, “Coal not dole [unemployment benefit]” was the slogan of the striking miners in the 1980s.)

marie-lucie said,

October 30, 2009 @ 5:46 pm

the great scene in Molière's Le Bourgeois gentilhomme where a tutor attempts to instruct Monsieur Jourdain in how to speak with a proper upper-class Parisian accent.

This is a great scene, but there is no suggestion that Monsieur Jourdain is not speaking "properly". Nowhere is the tutor actually correcting him. Instead M.J. gets the revelation that what he has been saying all this time is correct. Similarly, when he submits the sentence he wants to send to the lady he claims to be in love with, his own sentence turns out to be the best way to say what he wants to say. The point is his own insecurity, but there is no criticism of his way of speaking.

Jerry Friedman said,

October 30, 2009 @ 6:05 pm

Dudley Fitts's translation of Lysistrata uses a conventional southern (American) accent for the herald. Here are two snippets.

In The Frogs, Aristophanes made fun of an actor for pronouncing a word with the wrong tone, according to this. If I remember correctly, that's one of the pieces of evidence that Attic Greek still distinguished between different tones at that point, at least in the theater.

Jon Weinberg said,

October 30, 2009 @ 6:14 pm

Aaron or the first Andrew: So how did Talmudic-era Babylonian Jews pronounce aleph and ayin? Presumably there was a difference (if there wasn't, the passage displays a degree of snark completely uncharacteristic for the Talmud).

Bob Ladd said,

October 30, 2009 @ 6:40 pm

I also immediately thought of Catullus, but in a sense Panini's Sanskrit grammar – from several centuries earlier – is one extended peeve, aimed at fending off corruptions of sacred words.

Craig Russell said,

October 30, 2009 @ 6:49 pm

I'm digging on the Classicists on this thread! Can I add an example to the mix, based on a joke in Aristophanes's Frogs? At line 303-4, the character Xanthas says:

We can say, like Hegelochus did,

"For now, from out of the storm, I see the weasel again."

The joke here is that Hegelochus was an actor performing in Euripides' play "Orestes", written a few years before the Frogs. The line in quote marks is what Hegelochus was supposed to say, except the true line ending was:

γαλὴν' ὁρῶ—I see the calm

but Hegelochus accidentally mispronounced the accent on the first word:

γαλῆν ὁρῶ—I see the weasel

Apparently this change in accent was perceptible enough that the Athenian audience found it hilarious–at least enough so that Aristophanes could make a joke about it years later and people would know what he was talking about.

(So that's not exactly linguistic peevishness—but it's a pretty good story, I think).

Craig Russell said,

October 30, 2009 @ 6:51 pm

Wow, you can't give an example around here without someone beating you to it!

vp said,

October 30, 2009 @ 8:18 pm

The Sanskrit phoneticians could be considered peevers. The Rg-Pratisakhya, a how-to manual for pronouncing the RgVeda, condemns several faults in pronunciation such as lack of voicing in the "h" sound (which was supposed to be [ɦ], a voiced glottal fricative). I think it is said to date from around 500BC.

marie-lucie said,

October 30, 2009 @ 9:14 pm

So how did Talmudic-era Babylonian Jews pronounce aleph and ayin? Presumably there was a difference

In Biblical Hebrew, aleph is a glottal stop (produced by closing and then opening the vocal cords) and ayin is a pharyngeal sound (with the "tongue root" pushing back against the wall of the pharynx). Both sounds are distinct in some forms of Arabic too. But the related Akkadian language spoken in Babylonia at the time of the captivity seems to have had only the glottal stop, so Jews who had adopted Akkadian as a spoken language (or as one of their languages) could have been confused about how to pronounce the traditional Hebrew sounds.

MMcM said,

October 30, 2009 @ 10:07 pm

According to David Crystal's Think on my Words (pg. 59) and this site, the 1598 Quarto had abbominable, as John Cowan's edition has.

James Enge said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:28 pm

@Spell Me Jeff said

I'd agree that consistency is not one of Seneca's best traits (which is especially ironic given how much he insists on it as the touchstone of virtue). And, now that I've had a chance to flip through the letters again, it looks like it was actually letter 114 I was thinking of (especially sections 17ff), where he expresses some very severe and technical opinions on the usage of some Latin words (e.g. _facere_, verbified forms of _hiems_, _fama_ in the plural, etc). Then he does turn around and take, if not a contradictory, at least a complementary point of view in 115. That's Seneca all over, though. He contained multitudes. Wordy, sneaky multitudes.

Etl World News | PEEVERY IN SHAKESPEARE. said,

October 30, 2009 @ 11:37 pm

[…] at the Log, Mark Liberman adduces a nice bit of language peevery from Love's Labour Lost, where Holofernes complains about […]

Aaron Davies said,

October 31, 2009 @ 3:14 am

@marie-lucie: isn't there another bit where he gets instruction specifically on his accent? i thought i rememberd someone telling him how to form one of the vowels by sticking his lips out like he was going to spit.

John Walden said,

October 31, 2009 @ 4:31 am

Wilson's rant against linguistic change in his "Arte of Rhetorique" of 1553:

"Among all other lessons this should first be learned, that wee never affect any straunge ynkehorne termes, but to speake as is commonly received: neither seeking to be over fine or yet living over-carelesse, using our speeche as most men doe, and ordering our wittes as the fewest have done. Some seeke so far for outlandish English, that they forget altogether their mothers language. And I dare sweare this, if some of their mothers were alive, thei were not able to tell what they say: and yet these fine English clerkes will say, they speake in their mother tongue, if a man should charge them for counterfeiting the Kings English. "

(Sir John ?) Cheke's similar comment around 1560: “Our own tung should be written clean and pure, unmixt and unmangeled with borrowing of other tunges; wherein, if we take not heed by tym, ever borrowing and never payeng, she shall be fain to keep her house as bankrupt.”

William Caxton in 1490 (Prologue to Eneydos) :" And whan I had aduysed me in this sayd boke, I delybered and concluded to translate it in-to englysshe, And forthwyth toke a penne and ynke, and wrote a leefe or twyne whyche I ouersawe agayn to corecte it. And whan I sawe the fayr and straunge termes therin, I doubted that it sholde not please some gentylmen whiche late blamed me, syeing that in my translacyons I had ouer curyous termes whiche coude not be vnderstande of comyn people and desired me to vse olde and homely termes in my translacyons. And fayn wolde I satysfye euery man; and so to doo, toke an olde boke and redde therin and certaynly the englysshe was so rude and brood that I coude not wele understand it … And certaynly our langage now vsed varyeth ferre from whiche was vsed and spoken when I was borne … And that comyn englysshe that is spoken in one shyre varyeth from another. In so moche that in my dayes happened that certayn marchauntes were in a shippe in Tamyse, for to haue sayled ouer the see into Selande, and for lacke of wynde thei taryed atte Forlond, and wente to lande for to refreshe them; And one of theym named Sheffelde, a mercer, cam in-to an hows and axed for mete; and specyally he axyed after eggys; and the goode wyf answerde, that she coude speke no frenshe, And the marchaunt was angry, for he also coude speke no frenshe, but wolde haue hadde ‘egges’ and she vunderstode hym not. And theene at laste another sayd that he wolde haue ‘eyren’ then the good wyf sayd that she vnderstod hym wel. Loo, what sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte, ‘egges’ or ‘eyren’?"

Maybe not exactly peevish itself, but certainly a reference to the peeves of "some gentylmen".

Pekka said,

October 31, 2009 @ 5:52 am

This example is not really about peevery. But I like it nonetheless, so perhaps I can sneak it in here…

Early modern English extract at Google Books

It's an account in a "jest book" from around 1540 about a Scot who wants a carving of a boar head, but is misunderstood because of his northern accent. You can find it by searching for the phrase "it is a pigge" in case the URL above stops working.

Peter Taylor said,

October 31, 2009 @ 8:10 am

Now that I've seen your update, I still think Ulpian is an example of someone whose peeves were all incorrect – for every objection he raises, someone cites a quotation in counterexample. However, I can find only extracts of the Deipnosophists in text form (very bad OCR excepted).

[(myl) Interesting — I've never read more than a few quoted passages of this work myself. There seems to be a complete facsimile edition of a translation here — if you can locate the relevant passage(s) by book, that should be close enough.]

marie-lucie said,

October 31, 2009 @ 11:33 am

AD: isn't there another bit where he gets instruction specifically on his accent? i thought i rememberd someone telling him how to form one of the vowels by sticking his lips out like he was going to spit.

The elocution tutor demonstrates or describes how each vowel is pronounced, and M. Jourdain pronounces the vowel and is amazed that he is moving his lips exactly as the tutor says. In this case, this is how you pronounce the vowel written u in French. What the tutor is teaching is basically an elementary lesson in articulatory phonetics, not a correction of M. J's accent.

Sili said,

October 31, 2009 @ 3:14 pm

Bah. Talmud? Sanskrit? What kinda Yorkshiremen are you?!

Isn't it about time some dug up a cuneiform ancestor of Lynne Truss?

Peter Taylor said,

October 31, 2009 @ 7:09 pm

Yes, that's an example with bad OCR (not trained to read the Greek alphabet, but applied to it anyway; and it has some problems with the Latin alphabet too, although not surprising given that I find the text too small to read easily). Nevertheless:

p80: And when one of the Cynics used the word τριπους, meaning a table, Ulpian got indignant and said, "To-day I seem to have trouble coming on me arising out of my actual want of business; for what does this fellow mean by his tripod, unless indeed he counts Diogenes' stick and his two feet, and so makes him out to be a tripod ? At all events every one else calls the thing which is set before us τραπιζα." Against him are cited Hesiod, Xenophon, Antiphanes, Eubulus, Epicharmus, and Aristophanes.

Mind you, he's not the only one. When he attacks the Cynics, Cynulcus throws back on him a long list of his own and his friends' infelicities in word usage, starting p162 and ending with "And whence, O Ulpian, did it occur to you to use the word κεχορτασμενος for satiated, when κορεω is the proper verb for that meaning, and κορταζω means to feed?" – to which Ulpian in his turn finds citations.

They're about to kick off again on p176 but Myrtilus provides the citations and invites Ulpian to stop it.

p190: Cynulcus calls Aristomenes a freedman, and Ulpian wants to know who ever used that word.

p202: "But do not grudge, I entreat you, said Ulpian, to explain to me what is the nature of that Bull's water which you spoke of; for I have a great thirst for such words" raises the question of whether he's really peeving (as seems implied or even explicit elsewhere) or simply enquiring. (You might first have to answer whether he is speaking plainly, lying, or punning on the mention of water.)

p207 is clearly peeving: Give me, said [Ulpian], [s]ome crust of bread hollowed out like a spoon; for I will not say, give me a μυστρον; since that word is not used by any of the writers previous to our own time. You have a very bad memory, my friend, quoth Æmilianus; have you not always admired Nicander the Colophonian, the Epic poet, as a man very fond of ancient authors, and a man too of very extensive learning himself? And indeed, you have already quoted him as having used the word πεπιρων, for pepper. And this same poet, in the first book of his Georgics, speaking of this use of groats, has used also the word μυστρον.

If you go to the page you linked and click into the three volumes there's a search interface, so I shan't lengthen this post any more. It gives you a starting point, at any rate.

[(myl) Thanks! No question, Ulpian has precedence.]

dr pepper said,

October 31, 2009 @ 10:59 pm

So Yahweh didn't confuse the tongues after all. He just raised up a few peeving prophets who refused to abide each other's dialect.

K. said,

November 1, 2009 @ 5:21 pm

Just a note on the comic: seems that Wiley Miller is suffering from a recency illusion. A quick glance at urbandictionary turns up verbal use of "facebook" as early as November 2004, only 9 months after launch.

deadgod said,

November 2, 2009 @ 1:42 am

Shakespeare doesn't scruple to stoop to mocking accents by spelling words as (mis)pronounced and having characters understanding mispronounced and foreign words as though they'd been correctly pronounced- though whether the furr'ners or their English hosts are more risible is, in the Shakespearean style, your way to have. A funny extended example of this kind of low-but-rich comedy is the exercising of Latin (and of the 'tutor') in The Merry Wives of Windsor, IV. i.

Simon Cauchi said,

November 3, 2009 @ 9:10 pm

Dave asked: Was "than" spelled like "then" in Shakespeare's day?

Yes. E.g.

Sidney (1595): "But with none I remember mine eares were at any time more loden, then when . . . "

Spenser (1596): "A louely Ladie rode him faire beside, Vpon a lowly Asse more white then snow, . . ."

Jonson (1616): "Under-neath this stone doth lye As much beautie, as could dye: Which in life did harbour give To more vertue, then doth live."

Bacon (1625): ". . . many times, _Death_ passeth with lesse paine, then the Torture of a Limme: . . ."