More fun with Facebook pronouns

« previous post | next post »

Class discussion of the Facebook pronoun data brought out some interesting points.

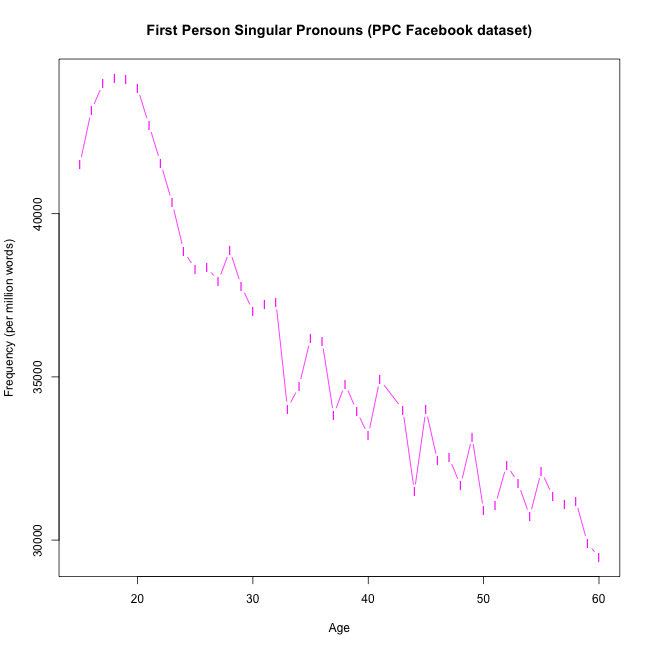

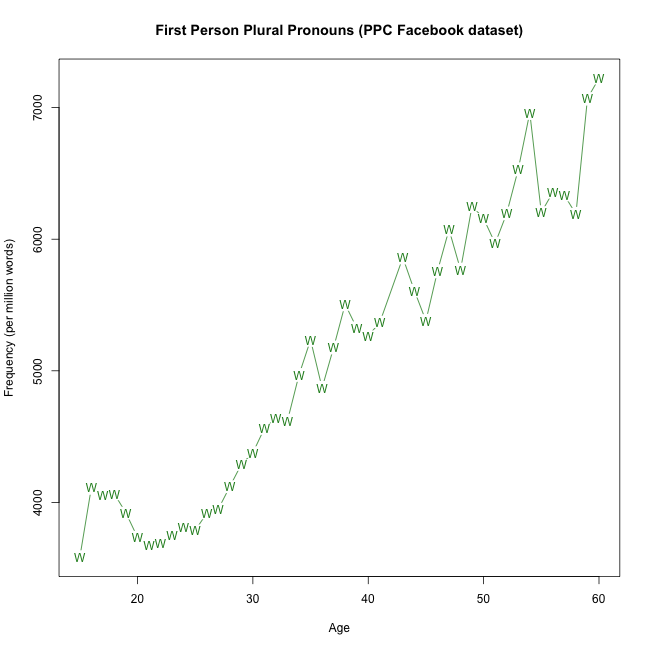

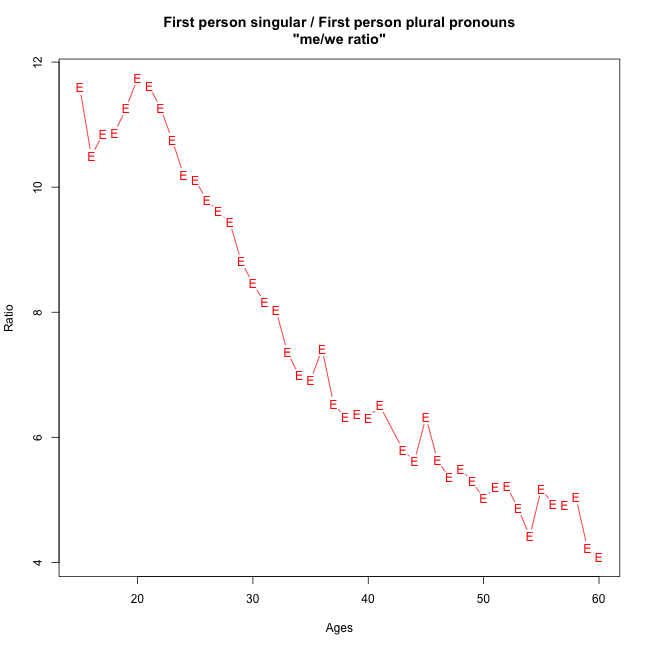

We started by looking at the relationship between first-person singular pronouns ("I", "me", "my", "mine") and first-person plural pronouns ("we", "us", "our", "ours") as a function of the age of the poster. Here's the ratio of FPS/FPP frequencies:

Before checking for confidence intervals, it looks like there's a big effect — from about FPS/FPP = 12 to about FPS/FPP = 4. And since the Ns are generally pretty large, and the pattern from age to age is pretty consistent, we can be confident that the trend will be a statistically significant one.

If we look at FPS and FPP frequencies as a function of age separately, as we did in the earlier post, we see that they have complementary changes that are both contributing to the trend in the ratio:

|

|

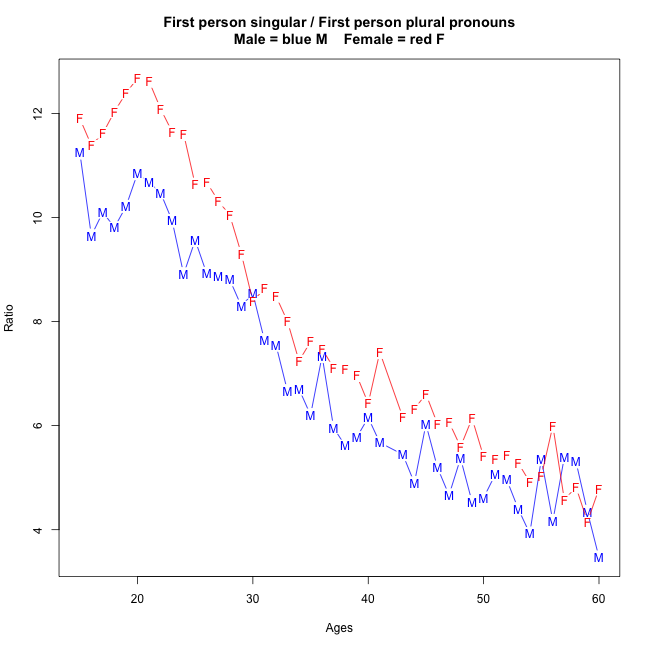

And if we look at the FPS/FPP ratios separately for male and female posters, we see comparable patterns, with a small female weighting towards higher FPS/FPP values:

Of course, there are lots of possible hypotheses about what this trend means. The most obvious idea is that people become more other-oriented (at least in their Facebook postings) as they get older. But in a dataset of this kind, we can't tell the difference between lifecycle effects (people changing as they get older) and historical effects (cultural changes over time, with older people retaining to some extent the patterns of an earlier era). So the researchers who think that Kids Today are "Generation Me" might be inclined to interpret this pattern as evidence for their hypothesis. (See e.g. "Lyrical narcissism", 4/9/2011; "Vampirical hypotheses", 4/28/2011; "Textual narcissism", 7/13/2012; "Narcissism in Emerging Adulthood", 8/6/2013.)

And I'm sure that readers can think of other ideas as well, as the students did in class discussion.

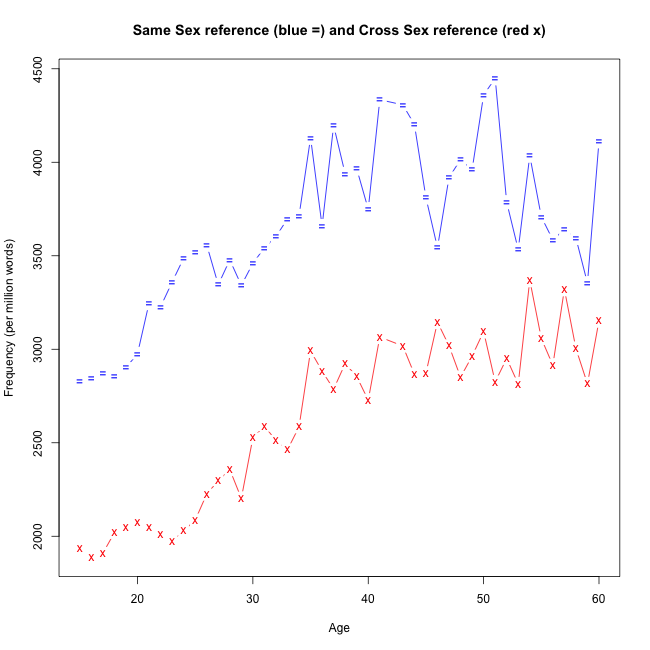

A plot of same-sex and cross-sex references via third-person singular pronouns also shows a clear pattern as a function of age:

In that plot, the blue = points are same-sex reference (male posters using he, him, his, or female posters using she, her, hers), while the red x points are cross-sex references (male posters using she, her, hers, or female posters using he, him, his).

At every age, Facebook posters refer to their own sex (via gendered third–person-singular pronouns) about 40% more often, on average, than they refer to the opposite sex. And the overall rate of animate third-singular pronoun usage increases steadily from age 15 to about age 35, at which point it levels out. (And gets noisier in this dataset due to smaller sample sizes at older ages.)

But this time, when we separate the data by the poster's sex, the picture changes.

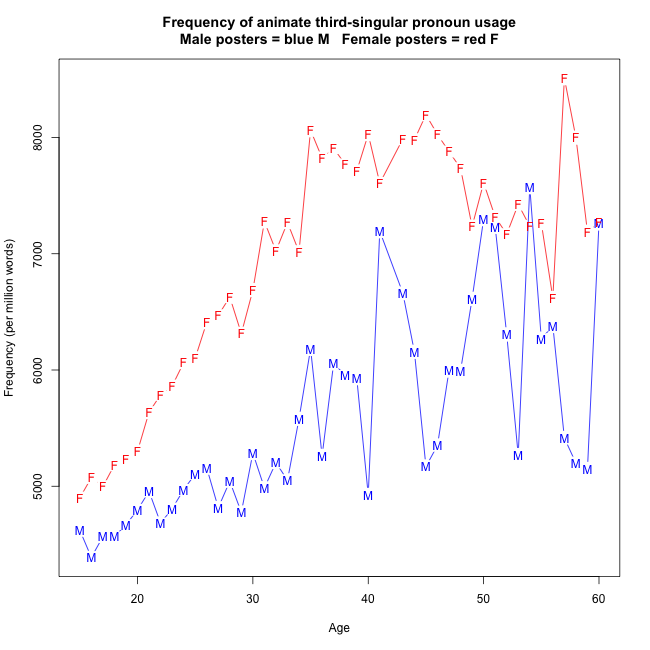

Looking first at the overall rate of animate third-singular pronoun usage, we see that the rate of overall third-singular animate pronoun usage (she, her, hers, he, him, his) is higher at every age for female posters than for male posters (ignoring the noise caused by the relatively small numbers of older male posters in the sample).

And the female advantage in animate TPS pronoun frequency widens with age. For ages 15-22, the median animate third-singular pronoun frequency is 12% higher for female posters than for male posters; for ages 35-60, the female advantage is 28%.

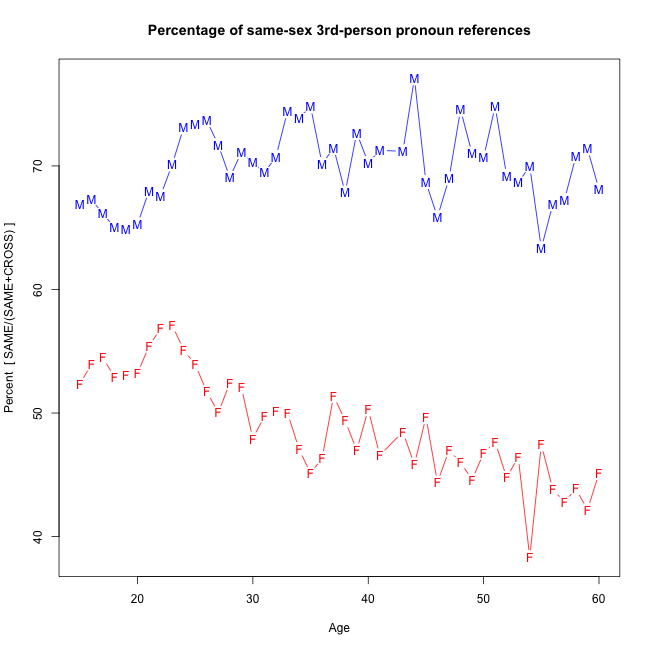

An even more radical change emerges in the patterns for same- versus cross-sex third-singular pronoun references, when look separately at the data for male and female Facebookers:

The median percentage of same-sex reference for male posters across the ages in this sample is 70%; the median for female posters is 48%. And the trends across ages of posters seem to be in opposite directions. At least it seems that older female posters are using increasing proportions of masculine pronouns, while male posters are not changing much after age 25 or so. These large differences look like bad news for the state of gender equality in contemporary American society.

As for the changes with age, we should again consider the possibility that this is frozen history rather than a life-cycle change — maybe younger people, especially younger women, are behaving differently from older people because times have changed since the old folks learned their habits. If so, then maybe history is moving towards greater gender equality. Or at least women are moving in that direction, along with males up to the age of 35 or so. A better test would be to look at overall sex differences in word usage as a function of age — that's a project for another day.

And then again, people surely do change in various ways as they get older, and maybe this is one of them.

It would be nice to explore a large collection of samples gathered across a couple of decades from a large number of people under comparable circumstances. But a disadvantage of the rapid pace of techno-social change is that we're not likely to get this, at least not from current sources of "big data". Can we really expect that Facebook will still exist in 2034, in anything like its current form?

Steve said,

September 27, 2014 @ 11:47 am

This reminds me of a phenomenon that seems ubiquitous among individuals of a certain age but not much discussed in language sites. Why is it that so many people under 30 have started using the first-person objective pronoun ("me") instead of the first-person subjective pronoun ("I") and inverting the standard order ("Me and X went to the store") when describing actions in which they and another individual participate? I've heard it argued that it used (though usually by much younger individuals) because the speaker feels that he or she should be the most prominent actor in the sentence but realizes that "I and X" sounds wrong, but that seems over-simplistic to me.

[(myl) I believe that you're a victim of the "recency illusion" here. Use of "me" as a subject form in conjunctions has been around for a long time:

A search of even earlier sources finds things like this, from 1825:

The Agent said, that me and my brother, Samuel Hawkins, ought to collect the Indians, when General McIntosh was gone to Washington, and burn down his houses and destroy his property, because of his disposition to sell the land.

The use of "me" in such contexts was discussed at length in Merriam Webster's Dictionary of English Usage (published 1994):

Everyone expects me to turn up as the object of a preposition or a verb […] But me also turns up in a number of place where traditional grammarians and commentators prescribe I. […]

While traditional opinion prescribes someone and I for subject use – I and someone seems a bit impolite — in actual practice we also find me and someone and someone and me […]

Both are speech forms, often associated with the speech of children, and likely to be unfavorably noticed in the speech and writing of adults except when used facetiously.

See "Patterns of prestigious deviance", 10/3/2011 for more discussion. It's worth noting that we can see this usage in effect treats "me" as the strong form of "I", so that "John and me" is analogous to "Jean et moi", which is the officially correct form in French, with "*Jean et je" being completely ungrammatical.]

Tanja S. said,

September 27, 2014 @ 12:21 pm

Interesting. The discrepancy between male and female use of cross-sex pronouns is also present in the British National Corpus (1990s British English) and in the Corpora of Early English Correspondence (where we analysed English letters from 1600 to 1800).

[(myl) VERY interesting. Are those results in any of your papers and and presentations? I didn't see them in a quick (though fascinating) look.

Eric P Smith said,

September 27, 2014 @ 5:28 pm

"Me and John did this" has been ubiquitous here in Scotland throughout my life. My primary (elementary) school teacher tried and failed to coach it out of us. Only posh kids and English kids said "John and I".

Tanja S. said,

September 27, 2014 @ 5:36 pm

myl: Those results haven't been the main thing in anything we've done and sadly aren't spelled out anywhere, but slide 14 in http://users.ics.aalto.fi/lijffijt/presentations/ICAME2012.pdf and slide 8 in http://www.cs.helsinki.fi/u/tsaily/presentations/icame34_mh_ts_tv.pdf show women's overuse of feminine pronouns (which is actually men's underuse of them) in the BNC (prose fiction) and the CEEC, respectively. Other people have noticed this in the BNC as well, e.g.:

Argamon, Shlomo, Moshe Koppel, Jonathan Fine and Anat Rachel Shimoni 2003. Gender, genre, and writing style in formal written texts. Text 23(3): 321–346.

Tanja S. said,

September 27, 2014 @ 6:00 pm

So basically our results have been that both genders use masculine pronouns at similar frequencies but that men use feminine pronouns clearly less often than women. Which amounts to similarly unequal proportions of same-sex reference as in your graph, although we haven't looked at the effect of age.

[(myl) Exactly — the earlier post presents things in a way that makes this aspect of the Facebook data very clear. Here are those two plots again:

Is this aspect of your research published yet? I'd like to be able to cite it.]

Tanja S. said,

September 27, 2014 @ 6:27 pm

myl: Some results on the BNC are included in an upcoming paper – I can send you the details via email. Unfortunately, the CEEC 3rd-person results didn't make it to our published paper, which focussed on 1st- and 2nd-person pronouns (http://www.cs.helsinki.fi/u/tsaily/publications/vartiainen_et_al_2013_preprint.pdf).

Sjiveru said,

September 27, 2014 @ 10:21 pm

I wonder how much of this is due to the fact that the older you go, the fewer people have a Facebook account – resulting in more accounts that are associated with more than one person (even if the account is ostensibly one person's). I can imagine an older couple where only one of the two has a Facebook account – they would use their account to talk about things the family as a whole is doing much more often than if each had their own account.

There may also be the 'Christmas letter' effect – older people are more used to informing each other of current events via sporadic updates with a wide scope, while younger people are more used to using shorter, more focused updates. That'll result in a much higher ratio of posts about family experiences to posts about individual experiences for older people than for younger people.

I doubt that too much of this effect is due to differences in usage patterns -when conveying the same information- – the differences seem to me like they'd be more due to a difference in content than a difference in framing content.

Schroduck said,

September 28, 2014 @ 4:36 am

The steepest part of the I/We graph seems to be between 25 and 35, which is of course the age when people start to get into marriage/serious long-term relationships and having children (which I would guess are the two biggest referents of plural first person pronouns).

I also find it interesting that in both graphs, there's a steady climb that peaks around 22. I wonder if this is an artefact of people leaving hometowns and later, leaving university, and therefore having to rebuild their social networks anew in new surroundings. It would be interesting to see whether this effect is also visible in the Corpora of Early English Correspondence, although maybe we shouldn't expect it to be – in an era where women lived with the family right until they got married, there might never be a time when they would need to use singular pronouns significantly…

GeorgeW said,

September 28, 2014 @ 7:25 am

@Schroduck: This occurred to me as well. As we get older, we form more stable relationships in which first-person, plural pronouns may be more appropriate. I suspect that this is an influence, but probably not the complete explanation.

I also wonder if there are any psychological-development studies, independent of language, that show a diminution of focus on self as a person ages.

David B said,

September 29, 2014 @ 11:47 am

Well, when i was 22 and single, i may well have been more likely to use the first-person singular to describe my day than now that i'm 44 and married. I'd suggest that this isn't a generational change so much as the fact that lifelong (or, at least, intended to be lifelong) opposite-sex pairings are more likely as you get older.

Similarly, i'm the father of daughters, and so now i would expect i'm more likely to talk about not just what my wife is doing, but what one of my daughters is doing, leading me to be more likely to use third-person feminine pronouns—and i'm probably even more likely to use first-person plural pronouns than when i was 33, even.

Now, if someone wants to dig down into people's public relationship statuses and determine whether these sorts of things are independent of such factors…