"Vampirical" hypotheses

« previous post | next post »

Several readers have sent in links to recent media coverage of C. Nathan DeWall et al., "Tuning in to psychological change: Linguistic markers of psychological traits and emotions over time in popular U.S. song lyrics", Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3/21/2011. For example, there's John Tierney, "A Generation’s Vanity, Heard Through Lyrics", NYT 4/25/2011.

[A]fter a computer analysis of three decades of hit songs, Dr. DeWall and other psychologists report finding what they were looking for: a statistically significant trend toward narcissism and hostility in popular music. As they hypothesized, the words “I” and “me” appear more frequently along with anger-related words, while there’s been a corresponding decline in “we” and “us” and the expression of positive emotions.

Or David Brooks, "Songs about myself", NYT 4/13/2011:

This result isn’t surprising or controversial, but it’s nice to have somebody rigorously confirm an impression many of us have formed. In an upcoming essay for the journal, Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity and the Arts, Nathan DeWall and others studied pop music lyrics between 1980 and 2007. They found that over these years lyrics that refer to self-focus and antisocial behavior have increased whereas words related to other-focus, social interactions and positive emotions have decreased. We’ve gone from “Love, Love, Love” to “F.U.”

Or "Study: Narcissism On Rise In Pop Lyrics", All Things Considered 4/26/2011:

So more than two decades ago, we were holding hands and swaying to the song of unity, and these days, we're bouncing to pop stars singing about how fabulous they are.

Psychologist Nathan DeWall has had the pleasure of listening to it all for research, and he found that lyrics in pop music from 1980 to 2007 reflect increasing narcissism in society.

Or Sandy Hingston, "Are today's kids narcissists?", Philadephia Magazine 4/27/2011:

Is there any hope for society amidst this onslaught of egotism? Jean M. Twenge, a co-author of DeWall’s study, has one suggestion for young people: “Ask yourself, ‘How would I look at this situation if it wasn’t about me?’” Unfortunately, that’s exactly the ability their overabundance of narcissism is unlikely to promote.

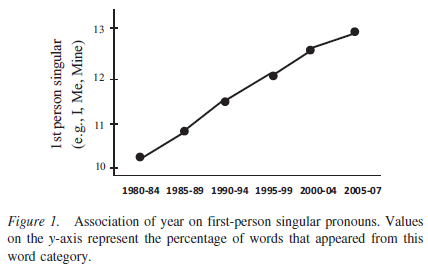

In "Lyrical narcissism?", 4/9/2011, I looked a little more closely at some of the data from this paper. See the original post for some additional details, but here's the authors' graph of (a parametric reconstruction of) their first-person singular counts:

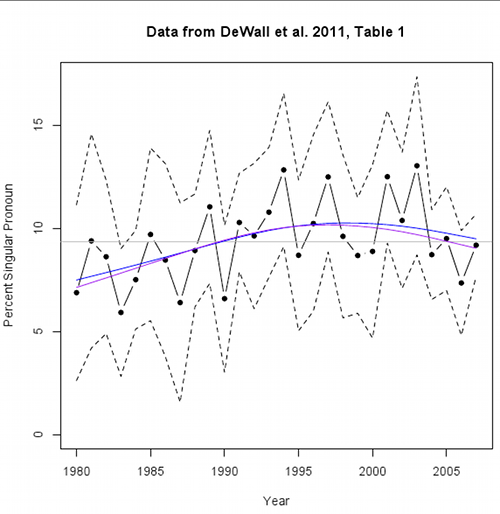

And here's Cosma Shalizi's graph of the actual corresponding data, with a spline fit, 95% confidence intervals — and a convenient horizontal line, which falls within the confidence interval in 27 out of 28 cases:

I'm going to resist the temptation to analyze the rhetoric of the media presentations of this work in greater detail, or to relate this episode to the Great Happiness Gap of 2009. Instead, I'm going to offer some links and quotes from two relevant sources.

First, Ben Goldacre, "I foresee that nobody will do anything about this problem", Bad Science 4/23/2011:

Last year a mainstream psychology researcher called Daryl Bem published a competent academic paper, in a well respected journal, showing evidence of precognition. […]

Now the study has been replicated. Three academics […] have re-run three of these […] experiments, just as Bem ran them, and found no evidence of precognition. They submitted their negative results to the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, which published Bem’s paper last year, and the journal rejected their paper out of hand. We never, they explained, publish studies that replicate other work. […]

We exist in a blizzard of information, and stuff goes missing […]

The same can be said for the New York Times, who ran a nice long piece on the original precognition finding, New Scientist who covered it twice, the Guardian who joined in online, the Telegraph who wrote about it three times over, New York Magazine, and so on. […]

What’s interesting is that the information architectures of medicine, academia and popular culture are all broken in the exact same way.

And second, Andrew Gelman, "Of beauty, sex, and power: Statistical challenges in estimating small effects", 9/10/2010, discusses "results [that] are more 'vampirical' than 'empirical' — unable to be killed by mere evidence".

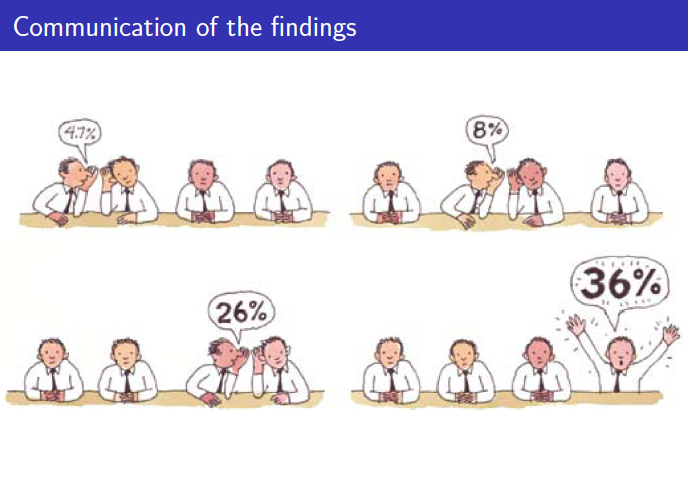

He dissects a specific case (S. Kanazawa, "Beautiful parents have more daughters: a further implication of the generalized Trivers-Willard hypothesis", Journal of Theoretical Biology 2007) which yielded an "estimated effect of 4.7 percentage points (with standard error of 4.3)" such that "95% confi dence interval is [-4%,13%]", from which Andrew concludes "Given that true e ffect is most likely below 1%, the study provides essentially no information". Nevertheless, through a fascinating chain of serial exaggerations, this work was featured by Steven Dubner in the Freakonomics blog as follows (emphasis added):

A new study by Satoshi Kanazawa, an evolutionary psychologist at the London School of Economics, suggests . . there are more beautiful women in the world than there are handsome men. Why? Kanazawa argues it's because good-looking parents are 36 percent more likely to have a baby daughter as their fi rst child than a baby son — which suggests, evolutionarily speaking, that beauty is a trait more valuable for women than for men.

Andrew's illustration:

Andrew observes that

When using small samples to study small eff ects, any statistically signi ficant finding is necessarily a huge overestimate.

And he notes that there are "incentives (in science and the media) to report dramatic claims".

My reluctant conclusion: if you read or hear about a scientific result in the mainstream media, the odds are depressingly good that it's nonsense.

Note — Andrew Gelman attributes the lovely "vampirical" coinage to Freese 2007, which appears to be Jeremy Freese, "The problem of predictive promiscuity in deductive applications of evolutionary reasoning to intergenerational transfers: Three cautionary tales", in Alan Booth et al., Eds., Intergenerational Caregiving, 2008.

Writing about the (ungeneralized) Trivers-Willard hypothesis, Freese observes that

Part of what makes the Trivers-Willard hypothesis perhaps more “vampirical” than “empirical”—unable to be killed by mere evidence—is that the hypothesis seems so logically compelling that it becomes easy to presume that it must be true, and to presume that the natural science literature on the hypothesis is an unproblematic avalanche of supporting findings. […]

In fact, the Trivers-Willard hypothesis of adaptive sex ratio variation is not at all well established in the animal kingdom. Adaptive sex ratio variation in birds—including but not limited to hypothesis that one could characterize as extensions of the logic of the TWH (see Frank 1990 for a review)—is discussed at length in a meta-analytic study as an example in which publication bias can lead to distorted conclusions (Palmer 2000). That author finds that “on closer inspection few, if any, compelling data exist for adaptive departure from a 50:50 sex ratio in any species” […]

The reason that animal results are relevant is that one can easily get the opinion that the TWH is a well-established phenomenon in animals and only through some pseudo-dualistic “human exceptionalism” might one resist its applicability to humans. Instead, we face the opposite of the famous line from “New York, New York”: if the hypothesis can’t make it there, should we expect it to make it anywhere?

Victor Mair said,

April 28, 2011 @ 6:41 am

"My reluctant conclusion: if you read or hear about a scientific result in the mainstream media, the odds are depressingly good that it's nonsense."

While that seems a bit extreme, I must admit that it fits fairly well with my experience in dealing with the mummies of Eastern Central Asia. I have been aghast at much that has been published in the mainstream media about the mummies and their culture. Far more reliable are small scale, specialist newsletters and blogs run by people who really care about some particular aspect of the research, such as textiles, for example.

MattF said,

April 28, 2011 @ 7:17 am

Maybe I'm naive, but… "…never publish studies that replicate other work"? Yikes. How about a 'Letter to the Editor'?

Alex said,

April 28, 2011 @ 7:40 am

Yea, I'm with MattF on this one. What does that say about that journal's commitment to the scientific method (i.e. reproducibility of results)? Is such a practice of rejection of work that attempts to emulate the findings of other scientists a typical phenomenon in the (social) sciences?

Brett said,

April 28, 2011 @ 8:05 am

I also find the journal's policy pretty incomprehensible. In my own field of physics, probably the easiest way to get something published in a top journal would be to repeat a measurement that produced an unexpected and much-publicized result–so long as you got a different result from the original one.

Dan Lufkin said,

April 28, 2011 @ 8:48 am

Doesn't the incubation temperature affect the sex ratio of reptile egg hatchlings? I'm pretty sure it's true of allligators, at least. Perhaps mothers in comfortable circumstances are less subject to cold. Not that mothers are alligators, of course.

Damon said,

April 28, 2011 @ 9:23 am

Ugh, Cosma's graph says it all, doesn't it? It's depressing that stuff as weak as this gets mainstream media coverage.

Also, I think it's sort of sneaky to use graphs like the first in publications intended for a general audience, since even the fairly numerate are not necessarily going to be as rigorous as we should be in looking at the actual values on the vertical axis.

[(myl) In my opinion, the biggest problem is not the range of values on the y axis, but the fact that the plotted points are not the actual data, but rather values reconstructed from (logistic?) regression on a set of much-less-impressive measurements.]

Marc Ettlinger said,

April 28, 2011 @ 9:50 am

I think we all lament the way things currently work. I'd be curious, in comments or in another post, to hear your thoughts on how things could be improved on academic end.

Advocating for the publication of replicated studies with different results isn't as easy as it seems. Presuming the initial study had a significant finding, the contrary replication will presumably have null results. Statistically there is nothing you can conclude from that – you can't say, for example, that the use of "I" hasn't changed over time if you're not significant.

That principle applies to behavioral experiments even more so, because a failure to replicate significant findings could mean a shortcoming in myriad aspects of the experiment, only one of which is a lack of tested effect. So again, you can't say "X doesn't exist," based on a null result. Absence of evidence doesn't imply evidence of absence, as they say. All the conclusion section of a failed replication could say is that they didn't get the same results and they don't know why, which isn't particularly illuminating.

So, what can be done?

One thought is that it would be great if it were typical to include in supplemental materials all the failed pilots that were conducted prior to the finding of an effect to get a sense of whether you are likely dealing with publishing bias. Another possibility is a repository of null results (e.g., http://www.jasnh.com/).

Does anyone have any interesting solutions to this very real problem?

[(myl) It's hard to disagree with Ben Goldacre's conclusion that "the information architectures of medicine, academia and popular culture are all broken in the exact same way", or with his prediction that "nobody will do anything about this problem".

The problem is not (anymore) that negative results can't get published — in some sense of "published" — but that false or misleading positives can't get rebutted with nearly as much impact as their original publicity got. Gelman and others have effectively rebutted Kanazawa's claims about the "generalized Trivers-Willard hypothesis", and even more strongly rebutted the absurd exaggeration of those claims in Freakonomics, but the number of people who have seen those arguments is several orders of magnitude lower than the number who read the Freakonomics exaggerations. This is not an accident, obviously — Freakonomics is popular because it offers a smorgasbord of "scientific" support for edgy and controversial claims. A later retraction, much less an extended demonstration that "things are not as interesting as you were told they were" doesn't have the same impact. (Not that Steven J. Dubner has ever corrected or apologized for his Kanazama exaggerations, as far as I can tell…)

For some additional relevant discussion, see "The business of newspapers is news", 12/10/2009, which also cites the demonstration in M R Munafò et al., "Bias in genetic association studies and impact factor", Molecular Psychiatry 14: 119–120, 2009, that the more prestigious the journal, the less likely the genetic association studies it publishes are to be successfully replicated.]

MattF said,

April 28, 2011 @ 10:45 am

There appears to be more information on this topic in Wikipedia's article on Meta-analysis:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meta-analysis

but I'm no expert…

MikeA said,

April 28, 2011 @ 11:18 am

"What about letters to the Editor?"

My very small (sample size one) experience suggests the affirmative.

The one such letter I have ever written (pointing out a serious bug in a published algorithm) was rejected. It was ruled "more suited to an article than for the letters column", and then rejected because "we have recently published a similar article".

Alan said,

April 28, 2011 @ 12:39 pm

"Dr. DeWall and other psychologists report finding what they were looking for"

I'd say that about sums it up, really.

KevinM said,

April 28, 2011 @ 2:41 pm

Timely, as always: Feynman's "Cargo Cult Science"

http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/51/2/CargoCult.pdf

In particular the bias toward the expected result, the resistance to publication of negative results, and the institutional resistance to reproducing earlier results, even where the validity of the current experiment wholly depends on them.

ohwilleke said,

April 28, 2011 @ 3:00 pm

One doesn't have to restrict oneself to popular culture song lyrics to find "I" and "me" coming into fashion. Its acceptability in formal academic writing has also surged (probably more dramatically) in a quite conscious ideological effort to put the identity of the author front and center in academic discussions.

Sili said,

April 28, 2011 @ 3:04 pm

Better or worse than Sturgeon's Law implies?

[(myl) About equal, I guess.]

Rubrick said,

April 28, 2011 @ 3:49 pm

Currently only perpetrators of blatant outright fraud (e.g. Hwang Woo-suk) face any real consequences. Mere shoddiness and unjustified spin aren't punished; in fact they're rewarded, especially when it comes to journalism.

It's hard to imagine the situation improving much without some sort of legal remedy, and it's hard to see what form that could take.

Mr Fnortner said,

April 28, 2011 @ 3:54 pm

Though vampirical rhymes so fortuitously with empirical, I think that zombie is a neater fit. Assuming that the theory in question has been killed by data, a zombie theory would be resurrected by a witch doctor, and would eat people's brains. That seems to be the essence of what happens with theories of this sort.

Jon Weinberg said,

April 28, 2011 @ 7:10 pm

@Mr. Fnortner:

John Quiggen had the same thought.

Martin Ellison said,

April 28, 2011 @ 11:45 pm

Jon Weinberg: Quiggin (http://johnquiggin.com/)

Keith M Ellis said,

April 29, 2011 @ 11:37 pm

"My reluctant conclusion: if you read or hear about a scientific result in the mainstream media, the odds are depressingly good that it's nonsense."

I don't think this is an exaggeration. It is a very good rule-of-thumb.

And it goes triple for anything that appears in Freakonomics.

"In particular the bias toward the expected result, the resistance to publication of negative results, and the institutional resistance to reproducing earlier results, even where the validity of the current experiment wholly depends on them."

I love science, have some training in science, much more training in the history and philosophy of science, and I think it's the crowning achievement of western civilization. But what Feynman describes, and especially the things you list, are very good examples of why the Platonic Ideal of The Scientific Method that I find is so frequently naively touted by many scientists as How Science Works and Why Science is So Awesome is a long, long way from being accurate. Kuhn is commonly dismissed by this sort as a crank.

And the odd thing about this is that one–well, I, really–have some expectation that trained and working scientists would have some personal rigor about attempting to speak authoritatively outside one's specialty. (Yes, yes, I know: in practice many scientists have Engineer's Disease.) You'd think a scientist would realize that being a scientist is related to, but quite distinct from, being knowledgeable, competent, and insightful about science itself as an object of study. Science is a cultural institution that operates quite a bit differently than the idealized and idealistic endeavor so many tend to claim that it is. "Repeatability", for example, is theoretically essential to the enterprise. In practice, however, there is often no attempt at all to truly replicate experiments. Grant money is scarce.

If there are systemic problems in the contemporary institutional practice of science–and there are–then we can only understand and correct them if we are able to understand science as it really is, and not pretend that it's what we wish it were but cannot ever be. It's deeply ironic that empiricists, of all people, would have an idealized view of the practice of empiricism.

Dwight Towers said,

May 9, 2011 @ 2:06 am

Vampire Hypotheses! Thanks for the intro. Agree with the commenter on zombies though – in climate change, the bad arguments have been killed so many times, but keep popping up again (funded by oil companies and/or revivivified by men who are unwilling to accept the implications of the science).

SO much of what the popular press talks about as "science" is tosh. I caught an example myself a while back, about men or women using more words. The story evaporated as you went looking for it…

http://dwighttowers.wordpress.com/2011/02/19/he-said-she-said-sort-of/

bill said,

July 7, 2011 @ 11:59 am

all this (and the comments) for some reason brings to mind the book Foucault's Pendulum