Slicing the syllabic bologna

« previous post | next post »

Yesterday afternoon, I got this note from John Cowan, that indefatigable correspondent:

You linked to the piece on Romney vs. Giuliani speaking styles today,

so I checked back to see if you ever added my comment on it, but I

think I probably sent it during the period when my mail to you was being mysteriously blackholed. So here it is again.

In fact, I recall getting John's comments the first time. But they brought up a problematic point that deserves a post of its own — the vexed question of "stress-timed" vs. "syllable-timed" languages — and so I put John's note on my to-blog list, where it languished until now. I still don't have time for a proper answer, but I'll respond briefly (hah!) under the rubric of fact-checking.

Here's the background. In yesterday's post on "Linguistic fact checking at the New Yorker", I linked to an earlier post on ways of talking about accents ("You say potato, I say bologna", 10/18/2007). That earlier post presented a bit of do-it-yourself fact checking, or maybe I should say "impression checking". Michael Schulman, writing in the New Yorker, quoted Beth McGuire, a dialect coach, giving this account of the speech patterns of two presidential candidates:

McGuire, who had listened to some of the previous night’s Republican debate, had noticed a striking disparity—aside from the one in economic policy—between Giuliani and his most formidable Republican opponent. “I’m used to listening to Giuliani. He was my mayor,” she said. “So here I am listening to Giuliani going dadadadada”—she made a machine-gun sound—“and then here’s Mitt Romney with this whole other pattern: dah . . . dah . . . dah . . . But Giuliani is who Giuliani is, and how we speak is who we are. Giuliani is a dadadadada guy.”

In my usual earnestly naive way, I tried to figure out what Ms. McGuire might have meant by this. At least, I concluded, it should imply that Giuliani spoke faster than Romney in the debate in question. But the day before, I had reported some speech rate measurements showing that Romney spoke faster than Giuliani (221 wpm vs. 206 wpm), and in fact, faster than any of the 17 then-candidates except Chris Dodd ("The tale of the tape: those fast-talking southerners", 10/17/2007).

Here's John Cowan again:

Well, when I read your article about Giuliani vs. Romney, I thought, Obviously Romney doesn't speak as slowly as that. But the term "machine-gun sound" aroused a dark suspicion in my mind, and when I heard the clips, it was confirmed.

Romney talks like an ordinary native speaker, as you'd expect. English is a stress-timed language, and his stresses are fairly isochronous with the slacks packed between them. This is what McGuire was mimicking as "dah…dah…dah…". For example, he starts with "Industry is shrinking here", four stresses and three slacks, followed by "jobs are going away this is just" in about the same time, although the four stresses have five slacks.

But Giuliani, though equally a native speaker, uses a syllable-timed delivery! I listened to the clip repeatedly, and it's unmistakable: except when pausing or hesitating, he makes his syllables come out at a nearly constant rate: "dadadadadadada…" Although he's a third-generation immigrant who shows no signs of knowing Italian, he must have grown up around Italian and Italian-flavored American, and somehow this single trait passed into his English, which otherwise is not Italian in phonology at all. How remarkable that is.

It would certainly be remarkable, if it were true. But the first problem is that I don't share John's intuition. Rudy Giuliani sounds like a New Yorker to me, and I don't hear any Italian prosodic substrate. And the second problem is the whole idea of "stress-timed" vs. "syllable-timed" languages, which is a gigantic tangled intellectual thicket that's easy to get into and hard to get out of. Luckily, though, John and I disagree about the speech patterns of two particular individuals on one particular occasion. This is easier to operationalize, and therefore to settle by experiment.

The idea that some languages are "stress-timed" while others are "syllable-timed" is an old one. It goes back at least to Ken Pike's 1946 Intonation of American English, but I believe you can find the concepts, and perhaps also the terms, in writers from the 19th century. My own opinion, which I won't try to substantiate here, is that the distinction says both too much and too little. Too little, because languages don't cluster into two neat categories with respect to the relevant prosodic features. And too much, because the empirical claim about timing, taken literally, is false. In allegedly "syllable-timed" languages like Italian, syllable durations are far from equal, due to the different intrinsic durations of different consonants and vowels, and speakers make no apparent attempts to equalize them. In allegedly "stress-timed" languages like English, inter-stress intervals are far from equal, for the same reasons, and speakers make no apparent attempts to equalize them. (In fact, when you ask English speakers to read doggerel in a way that emphasizes the rhythm, they exaggerate the intrinsic timing differences among the stressed syllables, which may make the stress-units even more unequal, in objective terms, than they were to start with.)

But this is a complicated and contentious issue, and there have been many ideas over the years about how to rescue the (clearly much-loved) stress-timed vs. syllable-timed distinction. You could write a book about it. (And then someone else would write another book, disagreeing with you.)

Anyhow, since the literal claim about syllables coming out "at a nearly constant rate" isn't true about Italian, it would be surprising to find that it's true about Rudy Giuliani's English. But in this case has a particular feature that makes it easy to test the idea. We don't need to compare a representative sample of speakers from two languages, in a representative sample of styles. We don't need to worry about how much deviation from isochrony would invalidate the idea, or how to judge whether speakers are trying to make selected speech units (syllables or stress-groups or whatever) more equal than they might have been under some null hypothesis. All we need to do is to compare Rudy Giuliani to Mitt Romney, in one debate that took place last October, and see whether Rudy's syllables are produced more at a more "nearly constant rate" than Mitt's.

So I indulged myself in a Breakfast Experiment™. I took the audio from one pair of answers during the debate in question ("Romney, Giuliani debate on tax cuts"), and segmented the first 133 syllables from each candidate's answer.

As expected, Mitt talked a bit faster: Rudy's mean syllable duration was 156 msec., while Mitt's was150 msec. But that doesn't matter — we're talking about rhythm, not rate. Were Rudy's syllables more constant in duration?

Not by any obvious statistical test. The standard deviation of Rudy's syllable durations was 76 msec.; Mitt's standard deviation was 73 msec. In both cases, the standard deviation was about 49% of the mean.

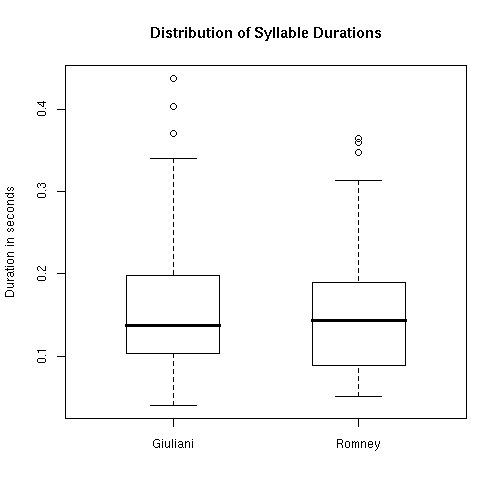

Boxplots of the duration distributions show an interesting difference, but nothing that I would construe as reflecting "syllable timing" vs. "stress timing". (The dark horizontal line is the median; the top and bottom of the box are the 25th and 75th percentiles; the whiskers mark the most extreme data point that is not more than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the box; the dots are individual points lying beyond that.)

I believe that the apparent difference in distributions reflects the fact that Rudy's answer was less fluent, though space and time don't permit a fuller discussion here. But John did say that it's "except when pausing or hesitating" that Rudy "makes his syllables come out at a nearly constant rate". So maybe most of Rudy's above-median syllables are associated with hesitations or pauses, and the remainder would show a "more nearly constant rate" than a comparable subsample of Mitt's syllables?

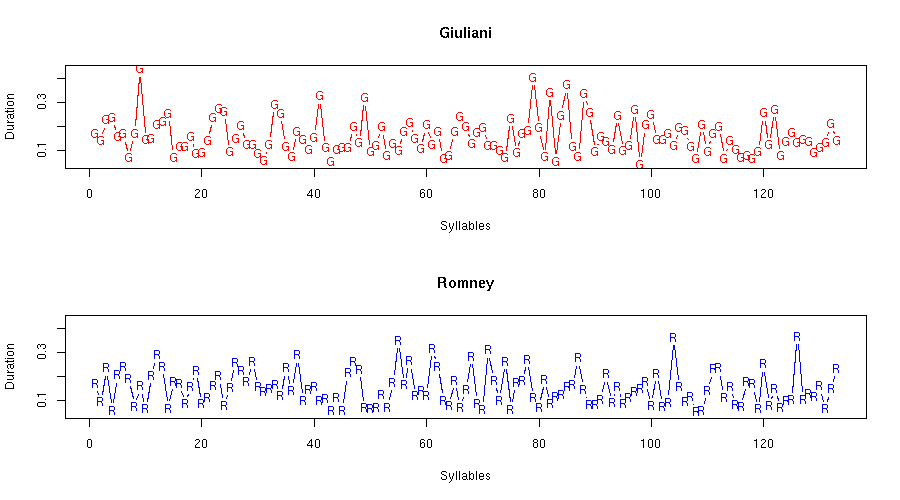

Maybe, but looking at the raw syllable-duration sequence doesn't persuade me that things are going to come out that way (click on the picture for a larger version):

John Cowan is an intelligent and insightful person, and he probably heard *something* besides a projection of dialect stereotypes. But I'm not sure about that. Anyhow, I'm pretty sure that whatever he may have heard, it wasn't syllabic isochrony.

[Note that I've avoided two critical questions here: how to divide a phonetic transcription into syllables, and how to align a phonetic transcription with the stream of sound. Depending on the answers, the concept "syllable duration" , applied to the same recording, will yield somewhat different experimental measurements; and therefore numbers and graphs are hard to interpret in the absence of well-defined standards for such annotation, which I haven't provided. So take my numbers and graphs as an example of how I claim such experiments are going to come out, and feel free to produce your own –though if we wanted to get serious about this, we should publish our annotation manuals, our audio recordings, and our raw segmentations.]

Robin Shannon said,

May 5, 2008 @ 8:44 am

I don't really know if your experiment is testing what you think it is testing. Isochrony across an arbitrary 133 syllables is irrelevant. Surely what should be tested for is stretches of isochronic syllables. It is irrelevant if the first syllable and the 133rd syllable are of equal length but whether the first syllable is of equal length to its surrounding syllables. One stretch of talk may be perceived to be isochronous and another immediately following stretch of talk may be perceived as isochronous without the two stretches having syllables of the same length.

[myl: Good point. And an excellent example of the indefinitely many ways that fans of isochronism can move the goalposts of proof, when some particular way of operationalizing the hypothesis turns out to be false.

I'm not about to test your hypothesis, though I'd be happy to see the results if you do the work. I'd be happy to learn that isochronism is true after all.

But I won't hold my breath, because in every experiment that I've done or seen, the facts are roughly as follows (once pre-boundary lengthening and similar effects are taken out):

If you compare renditions of a phase that is schematically …abcXdef… with one that is schematically abcYdef, where X and Y are very different in intrinsic duration, the timing pattern of the elements of the frame …abc__def… is not systematically changed in the direction of increased isochronism (of syllables or stress groups or whatever).

Similarly, if you compare renditions of a given speech element X in the frames …abc__def… and …ABC__DEF…, where the lowercase and uppercase letters represent sounds that are shorter and longer in intrinsic duration, the duration of X is not systematically changed in the direction of increased isochronism (of syllables, stress groups or whatever).

This is consistent with the null hypothesis, and hard to square with an isochronism theory.]

Jeff Sellin said,

May 5, 2008 @ 11:50 am

Just curious if any differences become apparent if you plot volume on the vertical axis

(as a rough approximation for linguistic stress, probably using a log scale–see http://forums.digitaltrends.com/archive/index.php/t-1120.html for discussion)

vs. elapsed time [or syllable count] on the horizontal axis?

A quick approximation might be to paste .wav files of the speeches into garageband- or protools-type mixing software to see if there are any discernible differences in timing from one stressed syllable to the next.

I grew up in the Midwest and moved to NYC 18 years ago. Whenever I'm on the phone with someone from back home, it feels like my speech slows down, but maybe there's just more time between stresses.

Jonathan said,

May 5, 2008 @ 9:30 pm

So then there's a pscyhological percpeption of syllable-timed language that is not visible in the objective data? Or is that the product of suggestion?

I'm wondering if intonational patterns play a role. In Spanish, for example, there can be a relatively long stretch of a phrase or sentence at the same pitch, between the first and last stressed syllables of the phrase. Those syllables tend to be perceived as a ratatatat sequence, even if their actual duration is not uniform.

[myl: A (partial) answer is here.]