Swearing and social networks

Swearing is risky behavior. Many of its implications are out of the speaker's control. Thus, it is advisable to know your audience well before, say, dropping the F-bomb. I think this is basically true in any setting, and I expect it to be even more powerfully felt in situations where swearing is highly transgressive.

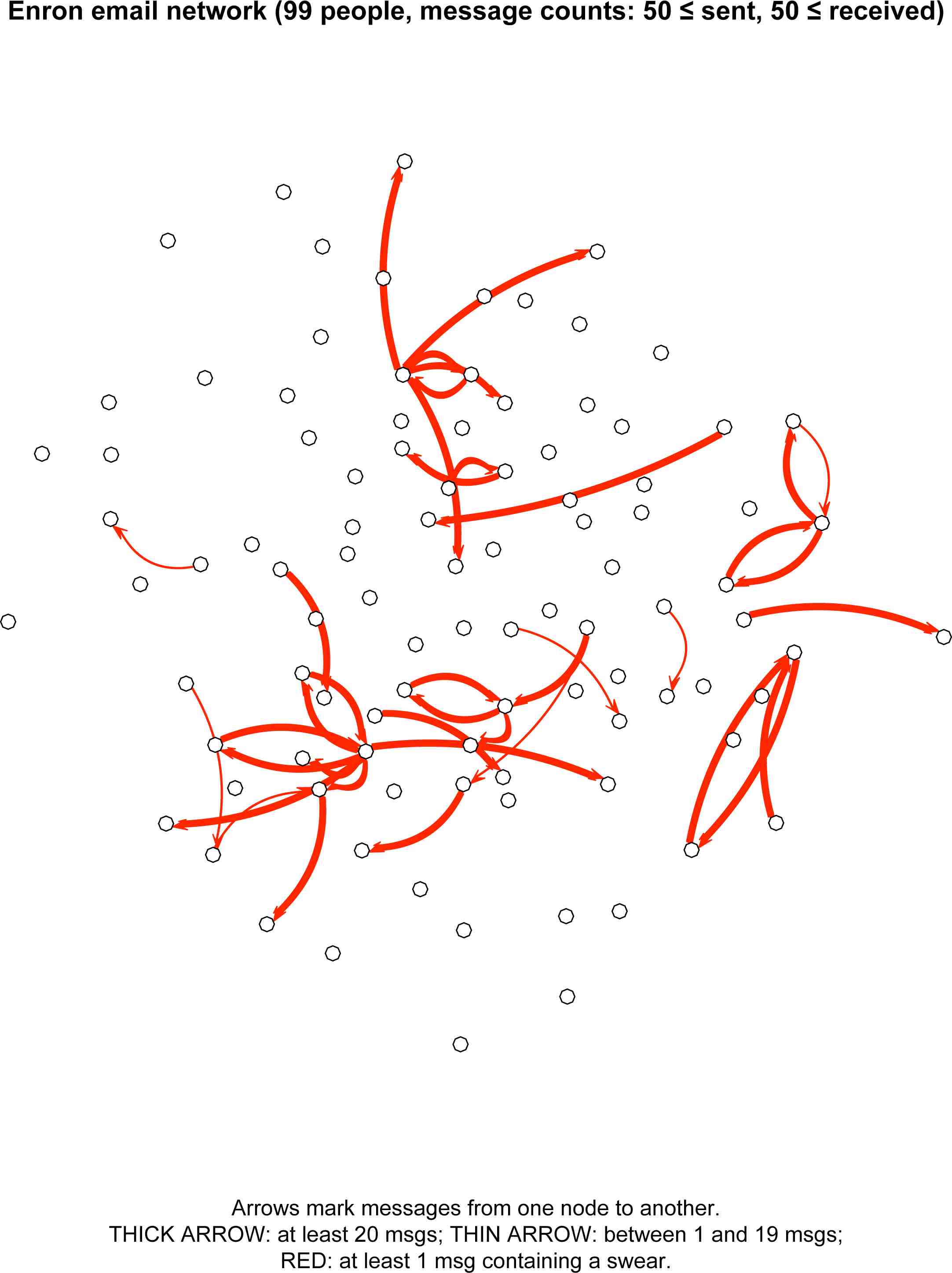

The Enron email dataset provides a nice chance to test out these claims. It is large (about 250,000 distinct messages, sent and received by over 11,000 distinct email addresses), and it contains a moderate amount of bad language. Not everyone swears, but a fair number of people do. The topics range widely: fantasy football, faith, energy markets, vacation time (and of course bankruptcy and the FERC). So, with some qualifications that I'll get to, it is a useful testing ground for claims about swearing and risky verbal behavior. The following email network graph is my first stab at conducting such a test:

Read the rest of this entry »