Please don't do nothing here: a Bengali conundrum

« previous post | next post »

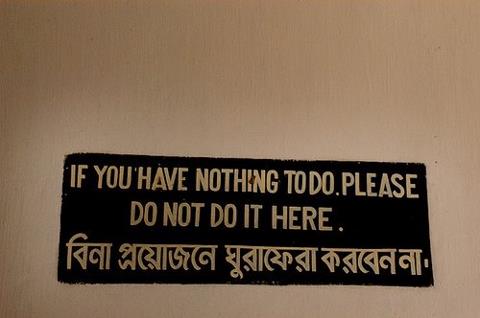

Sreekar Saha sent in this sign and expressed puzzlement over the English translation:

Before trying to figure out precisely what the Bengali says, I'd like to point out that, in essence, what the English says very politely is "Do not loiter" (not as strong as "No trespassing"). Telling people not to do nothing is not the same as telling them to do something.

Now, to tackle the Bengali. First of all, I was surprised by the variety of transliterations (not to mention translations) that I received from native Bengali speakers and Indologists. Perhaps this is due to the fact that there is no normative or standard transliteration for Bengali in English (I really don't know if there is or isn't). But I suspect that the differences in some cases may be due to dialectal and even idiolectal variation. For example, whether ফ is "f" or "ph".

I will give several of the transliterations for the sake of comparison. Then relying on charts from Omniglot and Wikipedia, you can follow along for yourself if you wish to do so (fortunately, the lettering on the sign is clear and distinct).

1. BINAA PRAYOJANE GHURAAPHERAA KARBEN NAA

(NOTE : AA stands for LONG A)

2. vinā prayojane ghurāpherā karven nā

3. bina prayojane ghurafera karben na

4. bina proyojone ghuraphera korben na

5. bina proyojone ghurafera korben na

6. bina proyojone ghurafera karben na

Here are some of the translations I received from the experts:

1. Do not loiter about if you have no business/nothing to do.

2. Don't wander around without purpose.

3. Do not hang around / wander without reason.

4. Without necessity do not hang out.

5. Without it being necessary, don't loiter / run around 'n stuff [here].

Leopold Eisenlohr, who provided the fifth translation, also offered these interesting notes:

Bina = without (probably same in Nepali? same in Hindi), proyojone= necessary, korben na = "you will not do" as a polite imperative, and ghurafera is more interesting. Ghura means to go around, spin around, as you would say for somebody running errands all over the neighborhood or something. In Bengali there is this lovely device of repeating the word with a different initial consonant, which gives the meaning "and stuff." Shower is chaan, so chaan-taan is "showering and doing all the other bathroom stuff like shaving etc;" packing-tacking means "packing and all the other stuff you do when you're getting ready to go on a trip. Usually the repeated word comes with a T, but I guess ghurafera just sounds better than ghura-tura.

[LATE UPDATE 1/21/14: Two native speakers disagree with this explanation of ghuraphera. See the comments of Debraj Chakrabarti and Native Speaker below.]

There's something about this sign (both in the English and in the Bengali) that leaves me pondering all sorts of existential issues. I have had the same sort of feeling after watching many a Satyajit Ray film, listening to Rani Shankar play an evocative raga, or reading a poem by Rabindranath Tagore.

[Thanks to George Cardona, Leopold Eisenlohr, Prasenjit Dey, Tansen Sen, Saroj Kumar Chaudhuri, Sunny Jhutti / Singh, Abdullah Mahmud, Philip Lutgendorf, and Fred Smith]

Jonathan Mayhew said,

January 16, 2014 @ 12:17 pm

It makes perfect sense to me in a kind of Yogi Berra way. (The original translation.) The other translations sound like awkward paraphrases of the perfect way of this pithy saying.

ajay said,

January 16, 2014 @ 12:23 pm

It seems to be related to jokes that rely on the two meanings in English of the word "nothing" – nothing meaning "a definite absence of things" and nothing meaning "no possible thing". As in "why is a cheese sandwich better than eternal bliss? Because nothing is better than eternal bliss, and a cheese sandwich is better than nothing".

Ginger Yellow said,

January 16, 2014 @ 12:27 pm

It makes perfect sense to me in a kind of Yogi Berra way.

Indeed.. Google throws up many instances of the phrase in English language contexts, and a Google Books search shows references going back to the thirties, including New York barber shop signs. .

Rube said,

January 16, 2014 @ 1:00 pm

Sounds like something for a Dashiell Hammett style hotel dick:

"What are you doin' here?"

"Nuthin'."

"Yeah, well if you're doin' nuthin', go do it somewhere else."

David Fried said,

January 16, 2014 @ 2:22 pm

The repetition device in Bengali sounds rather like Yiddish:

Hey, don't loiter in the lobby!

Loiter-shmoiter, I'm meditating here!

Is there a similar device in other languages?

David Morris said,

January 16, 2014 @ 2:31 pm

I can imagine someone being asked to move along, and retorting "But I didn't do nothing!"!

Matt D said,

January 16, 2014 @ 3:13 pm

Reminds me of this Language Log classic from myl:

http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/000012.html

cameron said,

January 16, 2014 @ 3:17 pm

@David Fried: I've heard similar constructions in Persian.

Joe said,

January 16, 2014 @ 3:29 pm

@Ginger Yellow: I agree it's less a translation and more of a meme that's been around for a while now.

Boris said,

January 16, 2014 @ 3:37 pm

@David Fried: This exists in Russian in this exact form without (I think) it being a Yiddishism

hector said,

January 16, 2014 @ 3:49 pm

Can't see any reason for confusion. I understood the intent right away. An amusing way of formulating that intent, however, for which I applaud the writer.

Tom S. Fox said,

January 16, 2014 @ 5:03 pm

“But I suspect that the differences in some cases may be due to dialectal and even idiolectal variation. For example, whether ফ is ‘f’ or ‘ph’.”

You do realize that “f” and “ph” are pronounced the same way?

BastianP said,

January 16, 2014 @ 5:07 pm

@David Turkish is said to have something similar

Avinor said,

January 16, 2014 @ 6:03 pm

Regarding the construction with a word repeated with a different starting consonant, what about hanky panky? Could it have Bengali or at least subcontinental origins? The etymologies that I can find don't sound too convincing.

Tairy said,

January 16, 2014 @ 6:10 pm

@Tom

In this context of Indic languages, 'ph' will be referring to the aspirated bilabial stop [pʰ], which depending on a number of circumstances may vary with the labiodental "f".

@Bastian

Azeri certainly does. pʃi : cat, pʃi-mʃi : stupid cats! (cats shmats)

richard said,

January 16, 2014 @ 6:16 pm

Indonesian/Malay has an interesting use of repetition in verbs, a bit different from Bengali, to indicate doing something for no particular reason. For example, "berjalan" means to walk (or travel by any method), whereas "berjalan-jalan" means to walk around with no particular destination in mind. Similarly, "berbelanja" means to go shopping, whereas "berbelanja-belanja" means the same as the English "window shopping"–going from store to store with no particular goal.

In some topolects, such as Manadonese Malay, the verbal prefix is duplicated rather than the verb stem (using those two terms loosely, I believe). So rather than changing "bajalang" to "bajalang-jalang," one changes it to "babajalang;" "babalanja" becomes "babablanja" and so forth.

When grading student papers, I have often wished English could do this, particularly with the verb "to write."

Victor Mair said,

January 16, 2014 @ 6:32 pm

@Tairy

"cats shmats"

Isn't that a very productive type of formation in Yiddish? Is it coming from German? Or is it just something within Yiddish? Hebrew?

Oh, I see that David Fried and others have already pointed this out.

Alex said,

January 16, 2014 @ 7:36 pm

I'll just say that I really like the original translation. If none of us knew that it was a translation and instead saw it independently in a part of the world that exclusively speaks English, would we have thought there was anything wrong?

Debraj Chakrabarti said,

January 16, 2014 @ 7:36 pm

Regarding Leopold Eisenlohr's explanation of "Ghuraphera":

(By a native speaker of Bengali):

Ghuraphera is not exactly analogous to the "echo word" "chan tan".

"Phera" is an independent verb meaning "to return". "Ghura" or "Ghora" is to rotate (intransitive) or to wander. The compound "Ghuraphera" means to wander. No doubt the formation of such a compound is similar in many respect to that of the echo words, but it is not precisely the same, since in an echo word the second half is just a repetition of the first word with the initial consonant changed, and the second half does not have a meaning.

One should note here that formation of echo words like "chan tan" is a general feature in the Indian language area — along with Bengali, languages like Hindi, Marathi, Oriya, Tamil and pretty much all Indian languages use this trick. The main difference is the use of different consonants in the "echo" part — instead of T in Bengali, Hindi uses w and Tamil uses k.

Pcv said,

January 16, 2014 @ 7:43 pm

Yes bina does mean without in Nepali. Also Nepali has that repetition but it lacks the disparaging connotations of Yiddish. It means more like "and stuff like that." So for example people might invite you over for tea (chiya) and say chiya-siya, meaning tea, cookies, conversation and everything else that goes along with inviting someone over for tea.

Anubhav Chattoraj said,

January 16, 2014 @ 8:16 pm

Here’s the statement in IPA:

/bina pɾɔjodʒɔne ɡʰuɾapʰeɾa koɾben na/

Phonetically, the /b/s are [b~β] while the /pʰ/s are [pʰ~ɸ]. The /n/s are dental.

Victor Mair said,

January 16, 2014 @ 8:37 pm

@Anubhav Chattoraj (and others):

Why do the transliterations waver /o/ and /a/ so much? Isn't the orthography unambiguous about which is which?

Leopold Eisenlohr said,

January 16, 2014 @ 9:17 pm

@Victor Mair:

Bengali like other Indic scripts is an abugida, each consonant symbol having an inherent vowel. In Sanskrit the default vowel is a short a (schwa) but in Bengali it's o most of the time. William Radice shows this as both ɔ and o as opposed to ô which represents the long vowel if it's written in. He says:

"In words which have inherent vowels in two consecutive sylables, the sequence will usually be ɔ/o, not o/ɔ. (Exceptions occur in prefixes such as pro-, ɔ-, or sɔ-.) Thus the word for hot is pronounced 'gɔrom', not 'gorɔm'.

"In words which end in a conjunct consonant + inherent vowel, the inherent vowel is always pronounced o. Thus 'Sukanta' above has to be pronounced 'sukanto', not 'sukantɔ'. "

It's hard to tell the difference in pronunciation between all three, since there's no real length difference.

Piyush said,

January 16, 2014 @ 9:24 pm

@Victor Mair:

I am a native Hindi speaker, and the little knowledge I have of Bengali comes mostly from talking to some of my friends who are native Bangla speakers. I think the issue in the /o/ vs /a/ problem is that in Bengali (unlike Hindi written in Devanagari), the implied vowel when no vowel markers are present can be either /o/ or /a/ (and, in my experience, it is mostly /o/). My (completely amateur) impression is that this is something like the schwa-deletion in Hindi, and as in that case, there are no simple rules for deciding when to use any one of the options (I have a suspicion the precise choices might also depend upon which dialect of Bangla is being spoken).

On a lighter note, there is a common joke among Hindi speakers that builds upon this phenomenon: it says that you can produce a passable imitation of Bengali by substituting all instances of the schwa in normal Hindi speech with /o/. Needless to say, my Bengali speaking fans are not amongst its biggest fans.

Piyush said,

January 16, 2014 @ 9:33 pm

Re. the word repetition device: Hindi has this too, and the folklore I heard as a kid was that this was borrowed from Punjabi. Also, as several readers have pointed out, "GHURAAPHERAA" (or the Hindi equivalent घूमना-फिरना, ghoomna-phirna) is not an example of this phenomenon: both components in this case are "real words", and can be used by themselves.

mcnugget said,

January 16, 2014 @ 9:55 pm

@ Avinor,

In English, there's also helter skelter, holy moley, itsy bitsy, teensy weensy, hotsy totsy, hurly burly…

mcnugget said,

January 16, 2014 @ 10:38 pm

Also, itty bitty, teeny weeny.

mcnugget said,

January 16, 2014 @ 10:49 pm

Also, razzle dazzle. There's something about four beats or syllables, like ghuraphera.

Nahid Ahmed said,

January 16, 2014 @ 11:28 pm

@Piyush:

Bengali speaker here. I have to correct you in that the inherent vowel in Bengali is either /ɔ/ or /o/, but never /a/. Although certainly can often be transliterated [a] because the inherent vowel corresponds to such in other Indic languages, as mentioned earlier.

It's funny that y'all have got such a joke about Bengali speakers, given that we have the opposite – the joke among Bengali speakers is that you can fake Hindi by substituting the inherent vowel with /ə/ and adding "hai" at the end of the sentence (Bengali has for the most part no present copula, but Hindi does).

richard said,

January 17, 2014 @ 12:19 am

@Nahid Ahmed, the dueling Hindi/Bengali jokes remind me of one from the U.S. Upper Midwest, here in Wisconsin.

Q. How do Swedes begin a joke?

A. There was this Norwegian….

Q. How do Norwegians begin a joke?

A. There was this Swede….

Q. OK, then how do Finns begin a joke?

A. A Norwegian and a Swede….

Roger Lustig said,

January 17, 2014 @ 2:39 am

@mcnugget: that's jiggery-pokery, if you ask me. Sorry to make your 4-syllable theory all higgledy-piggledy.

There's a poetic form based on these: the "double dactyl" poem. 2 stanzas of 4 lines, each one consisting of 2 dactyls. The 4th and 8th lines are truncated–instead of long-short-short-long-short-short they're long-short-short-long.

Further strictures: lines 4 and 8 should rhyme. Line 1 should be a repeated expression such as "higgledy piggledy"; line 6, if possible, should be a single 6-syllable word.

One of the very best New York Magazine Competitions called for such poems.

Anubhav Chattoraj said,

January 17, 2014 @ 2:45 am

To expand on what Leopold Eisenlohr and Nahid Ahmad said, the vowels in spoken Bengali don’t match the vowels in written Bengali.

Bengali has seven phonemic vowels: /a/, /i/, /e/, /ɛ/, /u/, /o/, /ɔ/ (no phonemic length distinctions). The orthography has eight[1] vowel letters, which are nominally[2] <ə>, <aː>, <ɪ>, <iː>, <ʊ>, <uː>, <eː>, <oː>.

Hindi and Marathi[3] use the English letter “a” for transliterating <ə>, while <a:> may be transliterated into "a" (same as <ə>) or "aa”. In Bengali, <ə> can stand for /o/, /ɔ/ or Ø, and so can be transliterated "o" (as per the Bengali pronunciation) or "a" (as per the pan-Indian convention).

This convention also explains why <aː> is sometimes transliterated “ā” or “aa”, despite there being only one a-sound in Bengali.

Notes:

1: ignoring <ঋ>, which is traditionally considered a vowel but is pronounced /ɾi/, the diphthongs <ঐ> and <ঔ>, and <ৠ>, <ঌ>, and <ৡ>, which don’t exist outside the abecedary.

2: i.e., according to the Hindi pronunciations of the corresponding Devanagari letters. For these vowels, the Hindi pronunciations match up more-or-less with the traditional Sanskrit pronunciations.

3: and probably most Indian languages, but I can only speak personally for these two

michael farris said,

January 17, 2014 @ 3:40 am

The English version has a kind of exotic-quaint charm. But I think it was probably not intentional. If the same sign were in a monolingual environment it probably wouldn't be taken too seriously

The Bengali version actually helps it because it orients the anglophone reader that the humor is probably uninentional.

It's also interesting (and kind of sad) that the English version is privileged over the Bengali version even though this the pictures was presumably taken in an Bengali language environment.

Azi said,

January 17, 2014 @ 4:28 am

It is not exactly the same in Persian, but might be close to a sentence which you might find in some shops in Iran (not very common recently; old usage).

توقف بیجا مانع کسب است

richardelguru said,

January 17, 2014 @ 7:05 am

@Nahid,

"you can fake Hindi by substituting the inherent vowel with /ə/ and adding "hai" at the end of the sentence (Bengali has for the most part no present copula, but Hindi does)."

So this suggests that Canadian English is much more closely related to Hindi than we realised, eh?

Joshua said,

January 17, 2014 @ 8:23 am

I'm curious (as someone who has NO clue about anything Bengali), is a possible literal translation (that makes grammatical sense, albeit sounds stilted in English) the following:

"Without necessity, please do not hussle-bussle [here]"

If so, I find it interesting that it's not really saying "don't just chill here without reason" but rather implying "Unless the business you are trying to take care of serves a mutual purpose for you and us, do it elsewhere"

In effect, they are both saying the same thing "Don't be here unless being here is serving a mutual purpose for us and you" but in the typical anglo way of saying it, we tend to perceive loitering as doing nothing/serving no purpose in a location that doesn't want people. The Bengali mindset would seem to take for granted that people would be busy and actively accomplishing tasks (ghura) and not doing nothing, so rather than asking them to not just twiddle their thumbs there, they are saying, don't be busy here.

Not sure if that makes sense to anyone.

Joshua said,

January 17, 2014 @ 8:24 am

I also found it interesting that there seems to be no need for the word "here" in the Bengali version. I can see how that would be implied, but it's interesting that (in a culturo-linguistic way) we alngo-speakers almost need to the word "here" or it would sound more like a proverb than a prohibition.

Victor Mair said,

January 17, 2014 @ 8:57 am

@Azi

Please transliterate and translate توقف بیجا مانع کسب است

mcnugget said,

January 17, 2014 @ 10:51 am

@Roger Lustig:

In jiggery pokery the vowel is changed. I was thinking of echoes where only the first consonant is changed. I've used higgledy piggledy but didn't recall it just then. Only remembered hickory dickory. Four-syllable ones come up easily. Humpty Dumpty, boogie woogie. Thanks for the information on the double-dactyllic poem. Composing such a poem would be a nice brain exercise. How does the brain search for these four-syllable and six-syllable echoic words in its memory, in any language? By playing the beat first?

Robert Coren said,

January 17, 2014 @ 10:59 am

The original translation is perfectly clear in intent, and reminds me of my husband's favorite description of our favorite Caribbean resort: "There's nothing to do, and not enough time to do it."

Piyush said,

January 17, 2014 @ 11:18 am

@Nashid Ahmed:

Thanks for the correction. I have heard the joke you mentioned too: the other features of Hindi that I have Bangla speakers joke about are the somewhat idiosyncratic gender assignments to everyday objects and the corresponding markings on verbs and possessives.

Sreekar Saha said,

January 17, 2014 @ 11:57 am

@Joshua,this was at a government office,where you wouldn't wan't people doing their work in the corridors(from what I'm getting of your comment).

Sreekar Saha said,

January 17, 2014 @ 1:03 pm

Also, @Naid Ahmed,that is just one of the problems students face in Bengali spelling.

Victor Mair said,

January 17, 2014 @ 4:08 pm

From Ramya Sreenivasan:

This is delightful! I found Leopold Eisenlohr's notes to be spot on about ghurafera. Loitering doesn't begin to capture it!

Mark Dowson said,

January 17, 2014 @ 10:25 pm

I don't see any problem with the English version (whether it is a correct translation or not). For example, a response to the question "What are you doing?" might elicit one of the responses:

– Eating

– Waiting for a friend

– Nothing

And the reply to any of these could be, quite reasonably, "Please don't do that here!"

Lugubert said,

January 18, 2014 @ 5:50 am

Slightly edited from D.C. Phillott, Hindustani Manual (1918):

A native, squatting by the roadside, might be asked what he was doing. He would probably reply: "I am doing nothing." A H.S. candidate would certainly [in their exam paper] translate it literally: Main kuch nahin karta hun [I – nothing at all – am doing]. The native idiom, however, would be (Main) aise hi baitha hun ("I'm just seated like this." [I] this, like, sitting am.)

Victor Mair said,

January 18, 2014 @ 8:32 am

@Lugubert

"I am doing nothing."

An American would probably say, "I am not doing anything."

Philosophically, what is the difference?

Sreekar Saha said,

January 18, 2014 @ 12:30 pm

I'm guessing that the translator(I'd choose the fifth translation:5. Without it being necessary, don't loiter / run around 'n stuff [here]) had tried to take the sections of the sentence and tried to translate them individually,while (in my case),when I heard that this sign was in a government office,translated it accordingly.But only the first part of the sentence " bina prayojane" has been translated well.

Having only the English,going back to Bengali(for me) (literally) "যদি আপনাদের কিছু না করার থাকে/বিনা প্রয়োজনে ,এইখানে কিছু করবেন না |Which sounds weird to my ears]

Sreekar Saha said,

January 18, 2014 @ 12:34 pm

@Tom S.Fox,you've never tried singing Rabindrasangeet,then.My teacher insisted repeatedly on the difference between 'ph' and 'f' when she taught me the song "phule phule dhole dhole".

http://www.geetabitan.com/lyrics/P/phule-phule-dhole-dhole.html (The lyrics,for those who are interested).

julie lee said,

January 18, 2014 @ 2:58 pm

Reading the New York Times this morning, I came upon an interesting use of "do nothing" in the obit of Mae Young, 90, a top woman wrestler, famed for her dirty wrestling. In a 2004 documentary she said:

"Anybody can be a baby face, what we call a clean wrestler. They don't have to do nothing. It's the heel that carries the whole show. I've always been a heel, and I wouldn't be anything else."

julie lee said,

January 18, 2014 @ 3:21 pm

Policeman to bum: "What are you doing here?"

Bum: "I'm not doin' nothin' here."

—–

Interesting grammar and logic, where "nothing" means its opposite "something". "Something" includes "anything".

Colin Fine said,

January 18, 2014 @ 4:47 pm

@Julie lee: no failure of logic or grammar (but the grammar in question is non-standard, though widespread).

It is a myth that "I'm not doing nothing" means something different from "I'm not doing anything". It is simply a variant which is grammatical in many varieties of English, and both the speaker and the hearer understand it as intended, unless the hearer wilfully misunderstands it to make a point.

[There are contexts where it could have the opposite meaning:

– Since you're doing nothing, will you come and help me?

– I'm NOT doing nothing.

but such contexts are marked, and require strong emphasis. ]

Sreekar Saha said,

January 18, 2014 @ 10:09 pm

@Colin Fine,that's fine.Seeing this in an official place was unexpected,to put it mildly.

MaryKaye said,

January 18, 2014 @ 11:09 pm

I think it's gone now, but for some years there was a sign on a certain door in the Health Sciences complex of my university which said:

"if you aren't going here

you can't get there from here

but if you go up one floor you can"

This seems to me to be an accurate, if hard to parse, way to say "This section doesn't connect to anything; go upstairs if you plan to go any further." It reminds me somehow of the sign in this post.

Victor Mair said,

January 20, 2014 @ 10:54 am

@MaryKaye

And that reminds me of a story about the distinguished professor of Sanskrit at Harvard, Daniel H. H. Ingalls, Sr. He was independently wealthy (owner of the historic Homestead Hotel in Virginia [see below for more details]). Though he taught a number of graduate students who later became influential in Sanskrit and Indian Studies, he was not very interested in teaching undergrads.

Ingalls' office was located deep within the bowels of Widener Library. The office was very hard to find, and he had no telephone. Furthermore, he did not like people to knock on his door unannounced, so he refused to put a name tag outside of his office. Consequently, when poor, hapless undergrads tried to find his office, they had a very hard time doing so, and would knock on the doors of the offices of professors that were next to Ingalls' office. In defense, they put up notices outside their offices that stated: "This is NOT the office of Professor Ingalls."

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_H._H._Ingalls,_Sr.

Ingalls' son, incidentally, is Daniel H. H. Ingalls, Jr., a famous computer programmer; very different kind of work from that of his father!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Henry_Holmes_Ingalls,_Jr.

Ingalls was chairman of the group that owned the famous Homestead Resort in Virginia.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Omni_Homestead_Resort

See the fifth and following paragraphs here:

http://www.thehomestead.com/history

Memorial Minute:

http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2010/02/daniel-henry-holmes-ingalls/

Graeme said,

January 20, 2014 @ 7:56 pm

The lawyer in me quibbles with Victor's aside about the mandatory always being softer than the prohibitory. 'Do not loiter' and 'no trespassing' both are blunt and seem to imply a miscreancy. A conditional mandate like 'If you have no business here, move on' seems no harsher.

Native Speaker said,

January 21, 2014 @ 7:00 am

(Coming from another native speaker):

As Debraj Chakrabarti pointed out, Leopold Eisenlohr is incorrect when he says that ghuraphera is one of these echo words (which Bengali does use liberally, this is just not one of them). As mentioned, phera here is a completely different independent word, with a meaning of its own. Taken together, they mean "walking around" and "coming back" which essentially amounts to "wandering around".

I think language log should append a correction to that effect in the main post, as people might take Mr Eisenlohr's to be the true explanation, since it's presented in some detail in this post even though it's incorrect, Bengali being not such a common language. (I'm not sure why no one's acknowledged Mr. Chakrabarti's correction so far, since he says he is a native speaker as well.)

Also, @michael farris: I'm not sure why you assume the humour is probably unintentional; I assure you Bengalis are quite capable of making this kind of joke in English.

Victor Mair said,

January 21, 2014 @ 7:57 am

@Native Speaker

Done.

Native Speaker said,

January 21, 2014 @ 10:40 am

@Victor:

Awesome, thanks! Sorry if I sounded a bit agressive; I'm a bit protective of my mother tongue, and having had bad experiences in the past (a "expert" guest lecturer talking about Bengali–at a South Asian Studies class at an Ivy League!–who misspelled basic words like "aami" (which means "I") on the blackboard, was angry when called out, and passed out Bengali books as if they were curiosities from a bygone age). In general I'm also a little sensitive to instances where a privileged voice is heard over a native one.

Language Log is typically great about this, though. Thanks again!

michael farris said,

January 21, 2014 @ 11:37 am

"I assure you Bengalis are quite capable of making this kind of joke in English"

That may well be. But should the message then be taken seriously? My reaction to such a sign would not be to conclude that I should leave if I have no official business. I might make sure that I don't make a lot of noise or run around a lot but I wouldn't understand that quiet waiting (sitting and or casual walking around) was not allowed.

Mark Mandel said,

January 23, 2014 @ 12:35 am

Having seen the English text on signs in the US fairly often (except with conversational "Don't" instead of formal "Do not"), I was surprised at the number of commenters who seem to think it is a translation, and that the Bengali is the original (Jonathan, Alex, Robert, Mark Dowson).

Michael, does that assuage your understandable discomfort any?

.

Victor Mair said,

January 23, 2014 @ 1:09 pm

@Mark Mandel

If you have seen the exact same English sign in America "fairly often", I'd love to see an example of it.

@Graeme

Actually, I was thinking of the difference between "loiter" and "trespass", not between "Do not…" and "No XXing", since I think that the force of the latter two injunctions is roughly the same.

michael farris said,

January 23, 2014 @ 2:31 pm

"Michael, does that assuage your understandable discomfort any?"

Nah, my discomfort is entirely about the (apparent) lesser status of Bengali in a place where it's presumably the main spoken language.

Sroyon said,

January 23, 2014 @ 2:54 pm

@michael farris: I'm not completely sure which city this sign is from, but Calcutta, the capital of West Bengal, has a significant number of people from neighbouring states, for whom Bengali is not a first or even a second language. This 2003 article puts the proportion at nearly 40%. In a government office, the percentage might even be higher.

michael farris said,

January 23, 2014 @ 5:04 pm

"has a significant number of people from neighbouring states, for whom Bengali is not a first or even a second language"

Then where is Hindi, you know the "national language"? Is it really more likely that those from neighboring states would know English better than Hindi?

Sroyon said,

January 23, 2014 @ 8:56 pm

The states four neighbouring West Bengal are Bihar (where the majority of people speak Maithili, Angika, Magadhi or Bhojpuri as their native language), Jharkhand (where they speak Hindi, Maithili and Santali), Odisha (where they speak Oria) and Sikkim (where they speak Sikkimese and Lepcha). Of course, most of them speak Hindi too, but whether they are more comfortable reading Hindi or English depends on many things including the specific area they are from, level of education and economic status. If this sign is in a government office in Calcutta, out of the three pair sets that can be formed from the set {Bengali, English, Hindi}, my guess would be that {Bengali, English} is likely to be understood by the most people (about 100%).

Sreekar Saha said,

January 25, 2014 @ 4:09 am

@Victor Mair,Professor Ingalls' example reminds me of the term "neti,neti"(not this,not this) used by Vedantins of Sankara's school.

Victor Mair said,

January 31, 2014 @ 7:04 am

From Joanna Kirkpatrick

I just heard from my long-time friend, Ghulam Murshid, formerly on the Bangla Lang. and Lit. faculty at Rajshahi U., now resident in London a few decades already, about his and his team’s new diachronic dictionary. I had to ask for the title and publisher (they are not here). He wrote:

==========

I do not know if you would remember that I was heading a project of 12 people to compile a diachronic dictionary. I worked for 3 years and a month and edited the very last page on Saturday last. I have never worked so hard on anything. It has turned into the largest Bengali dictionary (in 3 volumes, more than 3200 pages) and first ever Bengali dictionary on historical principle.

In this dictionary we gave the origin of each word, and then traced the first use of the word in written texts, with the extract, author and year. Afterwards, we tried to trace the changes of the word in form and meaning throughout centuries (until 1972).

The first volume has come out. The second one is expected to be out in the middle of February, and third in March. A copy of this dictionary will be presented to the PM tomorrow, and I came to Bangladesh on Wednesday to do it, in a ceremony (organised by the Bangla Academy).

==========

This is a prodigious contribution to the history of the Bengali language. I hope it achieves wide notice, here as well as abroad. Here is Murshid’s email contact: ghulammurshid@aol.com .

Leopold Eisenlohr said,

January 31, 2014 @ 1:06 pm

Thanks to those who replied with corrections to my mistake above. Not to excuse my ignorance, but I think it's interesting that a friend and native Bengali speaker answered "yes" when I asked that ghurafera was in the category of echo-words. Since it can be linked to the phrases in other languages of India like ghoomna-phirna, and is therefore not in the category of the likes of "chaan-taan," that makes me wonder why I and others would believe it to be. I guess it is in a more general category of Bengali (possibly extending to other languages of India) words that have a rhyming cadence to them, not unlike the English words (hanky-panky) others have pointed out?

That brings me to a larger question about knowledge of Bengali grammar and structure: in my experience it has often been difficult to get grammatical explanations from a native speaker of Bengali. I know I might be blasted for saying this and that it is a can of worms, but I would sincerely be interested in an answer. One example that comes to mind is the phrase "eta ki tomar chai?" which means "do you want this?" Literally "this – [question particle] – your – it wants." Having asked many people to explain it, none of whom could, it still doesn't unravel satisfactorily in my mind. First of all, is it in any way remarkable that grammatical explanations seem relatively hard to come by for Bengali? Any special circumstances or is that true the world over? Are there archaic constructions preserved in colloquial speech that an average person would not be expected to know (maybe something like how some people don't realize the phrase "til death do us part" means "until death parts us" using an old subjunctive form of "do")? Would anyone be bold enough as to give some observations on the colloquial language with respect to a "standard"?

Sreekar Saha said,

February 1, 2014 @ 6:24 am

Another amusing incident:A friend of my sister wrote a steamy love letter,but instead of স in a particular word,he put শ,completely changing the meaning of the letter and made himself look like a necrophiliac.

Both the letters share the same /ʃ/ sound.স also has /s/ sound,though that usage is less common.

I recalled the Mandarin signs on the blog saying "fuck the fruit".

On Wikipedia:

Three graphemes—শ talobbo shô "palatal s", ষ murdhonno shô "cerebral s", and স donto shô "dental s"—are used to represent the voiceless palato-alveolar fricative [ʃ], as seen in their word-final pronunciations in ফিসফিস [pʰiʃpʰiʃ] "whisper", বিশ [biʃ] "twenty" and বিষ [biʃ] "poison". The grapheme স donto shô "dental s", however, does retain the voiceless alveolar fricative [s] sound when used as the first component in certain consonant conjuncts as in স্খলন [skʰɔlon] "fall", স্পন্দন [spɔndon] "beat", etc.

Ghulam Murshid said,

February 1, 2014 @ 8:38 am

ghora-phera is not an echo-word. Ghura and Phira are both independent verbs. Ghora means to go around and phira means to come back or to loiter around. Chan-tan is truly an echo word. Ghora and phera together make it more unspecific – particularly with about the destination and time.

Ghulam Murshid said,

February 1, 2014 @ 8:45 am

More:

The exact translation of the notice: bina proyojone ekhane ghorphera korben na, is Do not hang around unless you need it (Stupid!).