Good good study; day day up

« previous post | next post »

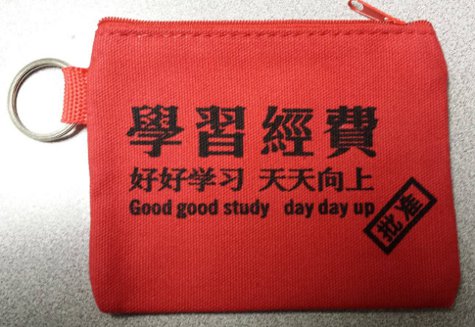

Somebody gave a friend of Rose Hill this coin purse as a gift:

Of course, "Good good study; day day up" is a classic Chinglish saying that is recognized by many who know no Chinese language and have nothing to do with Chinese studies. This deathless aphorism (or perhaps it is better to call it a slogan) has become a part of global culture in the 21st century.

Here (English) and here (Chinese) are images of "Good good study; day day up" in action, and here (English) and here (Chinese) are discussions of its significance and application.

I strongly urge all Language Log readers to take a look at some of the truly amazing depictions and sites devoted to the spirit of "Good good study; day day up" so that you will all be able to develop better study habits. Perhaps if you do, GKP might start opening his posts up to comments more often.

This is what the writing on the purse says:

xuéxí jīngfèi 學習經費 ("study expenses")

hǎohǎo xuéxí 好好学习

tiāntiān xiàngshàng 天天向上 ("Study hard and make progress every day")

pīzhǔn 批准 ("approve")

Note that, in contrast to the other lines, the first line is written in traditional characters.

A special gift awaits the Language Log reader who can document where and when Mao Zedong first uttered these immortal words.

David Mackinder said,

January 14, 2014 @ 6:51 am

Invoking the power of Google Book search, it seems that, according to Geremie Barmé (ed.), _Shades of Mao: the posthumous cult of the great leader_ (ME Sharpe, 1996), p. 268, n. 8, it is a conflation of two inscriptions by Mao, the first part being from the inaugural issue of a magazine called Zhongghuo ertong (China’s Children) that appeared in 1949; the second, to commemorate Children’s Day, from the publication Xin Zhonghua bao in April 1940.

Daniel Tse said,

January 14, 2014 @ 7:04 am

A bit of propaganda from the early days of the People's Republic — in 1951, Chen Yongkang in Suzhou thwarted a counter-revolutionary plot to blow up his school.

Recognising that one should never accept candy from strangers, he alerted the PLA to the fact that a terrorist wanted his classmates to plant explosives on his teacher's desk…

Daniel Tse said,

January 14, 2014 @ 7:05 am

You'd think the Chairman's advice would be a little less generic than "Keep studying, kid. Don't stop believing."

Tom said,

January 14, 2014 @ 8:05 am

What I find interesting is the tone sandhi in "hǎohào xuéxí 好好学习." Don't two third tones usually become a second + a third (e.g., nǐ 你 + hǎo 好 = níhǎo 你好)?

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 9:02 am

@Tom

Thanks for catching that typo (fixed now). It certainly should be hǎohǎo –> háohǎo.

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 9:05 am

Should I give duplicate awards to David Mackinder and Daniel Tse — to the former for historical accuracy, to the latter for creative imagination?

Tom said,

January 14, 2014 @ 9:07 am

@Victor Mair

But when I hear people say it, it usually sounds something like hǎohāo or hǎohào (but my ear isn't terribly good at these things). Is there actually something weird going on with the tone sandhi of reduplicated hǎo 好, or am I just hearing things wrong?

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 9:23 am

@Tom

You are on to something very significant. I hope that the phoneticians and native speakers weigh in on this. Stay tuned. I'm sure that we'll be hearing a lot more on this during the coming hours and days.

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 9:25 am

Rose Hill (Dallas, Texas) says "coin purse" 2,110,000 ghits

Victor Mair (East Canton, Ohio) says "change purse" 339,000 ghits

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 10:31 am

From Grace Wu, teacher of Mandarin and Taiwanese at Penn:

I am from Taiwan and will pronounce hao2 hao3 xue2xi2

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 10:40 am

The following three replies are all from teachers at Penn

Melvin Lee (from Taiwan):

We tell students to pronounce it as hǎohāo(r) xuéxí, as is written in the textbook. However, I know in Taiwan, many people pronounce it as hǎohǎo xuéxí

Liwei Jiao (from the PRC):

I always say it like 'hao3haor1 xue2xi2' and it is also what I always heard.

Maiheng Dietrich (from the PRC):

Beijingren say hao3 hao1 xue2xi2.

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 10:45 am

From Gloria Bien, professor of Chinese at Colgate:

If you mean for "hǎohǎo," this is one place where my childhood Chinese jibes with textbook Chinese. We say hǎohāo , or hǎohāor, as in "hǎohāor wár." (不许打架,好好儿玩儿)。We never said "háohǎo " as one word or "xuéxí." I learned the latter from textbooks.

I love some of the products illustrated in the links!

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 10:48 am

From Jianjing Kuang, phonetician at Penn:

There are two possible pronunciations for haohao:

hǎohāo more frequent in daily use. as in 你要好好学习。

or háohǎo as in 好好学习,天天向上!

You noticed a very interesting phonological rule in Mandarin: for reduplicative adjectives, the second syllable usually gets reduced into a neutral tone. And because this rule applies, the usual sandhi rule can't apply. So you normally have the first pronunciation instead of the second. But the second pronunciation is certainly acceptable.

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 11:07 am

From Brendan O'Kane:

Non-native speaker here, but if speaking at normal speed (rather than overemphasizing things, as people tend to when making declamatory statements like this one), I think I would probably produce something like hǎohāo xuéxí, with the second ‘hao’ being shorter in length than a regular first-tone syllable. Outside of this context, in e.g. a sentence like "你好好好兒的,” I’d probably pronounce the second ‘hao’ as a longer syllable.

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 11:09 am

From Sanping Chen (native of Hangzhou):

I am not a native Mandarin speaker, Victor.

Nonetheless, standard BJ dialect has this tone sandhi, in that when

you have two characters of the third tone together, both characters

change tones. I forget the exact details. Just ask a native BJ person

to pronounce it.

ahkow said,

January 14, 2014 @ 11:14 am

Dr Jianjing Kuang said:

"You noticed a very interesting phonological rule in Mandarin: for reduplicative adjectives, the second syllable usually gets reduced into a neutral tone. And because this rule applies, the usual sandhi rule can't apply. So you normally have the first pronunciation instead of the second. But the second pronunciation is certainly acceptable."

1. The second syllable appears to be of a high tone, not a neutral tone – compare the contours of e.g. 好好 hao3hao vs. 好了 hao3le. So is this actually tone neutralisation?

2. To what extent is this a "rule" if it applies unevenly? Of adverbs/adjectives, other than 好好, I can only think of 慢慢 man4man4 / man4man1 "slowly" that exhibits such a property. Most other reduplicated adverbs don't do this – e.g. 明明 ming2ming2 / *ming2ming1 "obviously", 傻傻 sha3sha3 / *sha3sha1 "foolishly", 快快 kuai4kuai4 / *kuai4kuai1 "quickly".

3. In at least my dialect of Mandarin, certain kinship terms display the same property, although again the "rule" appears to be the exception rather than the norm: 嬸嬸 shen3shen1 "wife of younger brother", 嫂嫂 sao3sao1 "wife of older brother", 奶奶 nai3nai1 "(paternal) grandmother", 姐姐 jie3jie1 "older sister". But contrast this with 妹妹 mei4mei(4) "younger sister", 爺爺 ye2ye(2) "(paternal) grandfather", 舅舅 jiu4jiu(4) "mother's male sibling".

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 11:22 am

From Jing Wen, native of Beijing:

I think people say hao3hao1 xuexi instead of hao3hao3. But I do hear hao3hao3 xuexi in some dialects. Maybe in 东北话, I am not sure.

Anna said,

January 14, 2014 @ 11:39 am

In I think my first year of studying Chinese I learned it's hǎohāo'r de, mànmān'r de, for 'well' and 'slowly', but hǎo hǎowán -> háo hǎo wán, because there, the first 'hao' means 'very' and the second one 'good'. Basically. I assume there must be some good grammars that explain this.

妹妹, little sister, in Taiwan also often becomes měimēi when used to address a little girl who is not necessarily anyone's sister, although I don't think the same happens with 弟弟. The same happens to 狗狗, when talking to little children about cute doggies (or when talking to cute doggies), it's gǒugōu not gǒugǒu.

JS said,

January 14, 2014 @ 12:50 pm

@ahkow

"In at least my dialect of Mandarin, certain kinship terms display the same property, although again the "rule" appears to be the exception rather than the norm: 嬸嬸 shen3shen1 'wife of younger brother', 嫂嫂 sao3sao1 'wife of older brother', 奶奶 nai3nai1 '(paternal) grandmother', 姐姐 jie3jie1 'older sister'. But contrast this with 妹妹 mei4mei(4) 'younger sister', 爺爺 ye2ye(2) '(paternal) grandfather', 舅舅 jiu4jiu(4) 'mother's male sibling'."

You mention the third-tone kinship terms where this tonal pattern is ubiquitous in Mandarin… more novel is the stuff Anna is talking about, though often the pattern you hear in the south for the words in the north pronounced māma, bàba, mèimei, and dìdi is (low)3+2; e.g., měiméi, etc. Some explain the last in terms of influence from a "different word" měiméi 美眉, but this is of course putting the cart before the horse. Instead, some sort of "intimate/familiar" semantics is becoming associated with this patterning, perhaps the same thing producing Anna's gǒugōu and the like (maybe these words involve a neutral tone with tone 2 as a realization for some southern speakers?.)

—

Not sure how relevant, but it's notable also that in ABB expressive adjectives, tonal patterning tends towards X11 and X22 (热乎乎 臭烘烘 傻乎乎 红彤彤 黑乎乎 圆溜溜 亮晶晶 爽歪歪 脏兮兮 笑嘻嘻 笑眯眯 香喷喷 胖乎乎 慢吞吞 / 慢腾腾 暖洋洋 软绵绵 热腾腾, etc.) Again, one can't just say that such happen to be the tones of the particular characters involved, as the tonal pattern has driven the selection of characters and not vice-versa.

Jiajia said,

January 14, 2014 @ 2:03 pm

I second Jiao laoshi's pronunciation: hao3haor1 xue2xi2. However, I do remember hearing people saying: hao3hao3 xue2xi2, as in movies by non-Beijingese.

Guy said,

January 14, 2014 @ 6:03 pm

好好學習would be pronounced hao2hao3xue2xi2 in Taiwan.

I wasn't aware that there was any other way to pronounce it actually!

Having said that, we sometimes change the pronunciation of 好 such as in 愛好 (ai4 hao4).

妹妹 (little sister) can be pronounced 美眉 (mei3 mei2) in Taiwan if one wants to sound childish or cute. We actually often write it out as 美眉 to indicate the cute pronunciation. Similarly 弟弟 (little brother) is often written or pronounced as 底迪 (di3 di2).

The cute pronounciation can be used for lots of things. For example I onced heard a young toddler refer to his banana as jiao3 jiao2 instead of xiang1 jiao1!

Guy said,

January 14, 2014 @ 6:08 pm

Actually I've changed my mind. I just pronounced 好好學習 in my head as hao3hao1xue2xi2 and the alternate pronunciation sounds fine too. I can totally imagine someone saying it that way in a Taiwanese TV drama!

Perry Link said,

January 14, 2014 @ 7:41 pm

Fascinating stuff, people. I have two comments and a question.

Comment one: let's not forget the immense variability. Those of you pointing out that child-talk can be standardly different from adult-talk are right–to say nothing of all the regional variations. So it is possible almost everyone is right here.

Comment two: Someone mentioned that if a second syllable is in neutral tone then tone sandhi doesn't apply to the first. That's a mistake. It almost always does apply: 海里 ,一个, etc. Family terms like 姐姐 and 奶奶 are exceptions.

Question: I have a feeling there is a subtle distinction in meaning between hao3hao3xue2xi2 and hao3haor1xue2x2 in Beijing Mandarin. The first seems long-term advice, about the right way to behave yourself during your school years. The second seems more short-term advice, like what a parent might say as a child leaves home for school today. Moreover the first is (always?) intransitive, whereas the second can take an object: hao3haor1 xue2xi2 第五课。

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 7:54 pm

Girl Talk: Lisp in Beijing Dialect?

From Sanping Chen (see above):

The last character xi2 in this phrase (and the family name of the

current CCP top honcho) reminds me of the following experience. Many

years ago, I observed that female BJ speakers often changed the pinyin

consonant x- in xi into something close to English th- (or something

between s- and th-). The strange thing is that all my male friends

from BJ pronounced the sound normally. This was more than twenty years

ago and I am not certain if it is still the case today.

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 8:20 pm

Would someone in Beijing please do me the favor of buying 5 of the pictured change / coin purses? You might find them in the 798 Art Zone. I need them to give away as awards and gifts (and to keep one for myself). Naturally I'll reimburse any and all expenses.

Victor Mair said,

January 14, 2014 @ 8:22 pm

From Tsu-Lin Mei:

The comments are interesting and got me confused. When I was teaching Mandarin Primer at Harvard, I got into the habit of looking up the text when in doubt. (And we were expected to teaching according to the text and the gramophone recording of Y.R. Chao and Iris Pian). The index gives: haohaul(.de) , which means the first syllable is in the third tone and the second syllable is in the first tone. My teaching experience also taught me that do not trust the intuition of the native speaker, and I can only be called an ex-native speaker of Mandarin. Having spent 8 years in Shanghai, I really lost my native Pekingese. As we were all brought up by our nurse, my original Pekingese is much more colloquial than Putonghua.

Wentao said,

January 14, 2014 @ 8:24 pm

Very interesting post! I have always pronounced either hao2hao3 or hao3haor1. The latter is certainly the standard form in Beijing dialect, and sounds more colloquial to me.

@JS

Not only that; in elementary school I was taught to read the tones of ABB words differently, for example 绿油油 and 毛茸茸 as 411, rather than 422.

@Sanping Chen

I have also come across lisp among people who are not only from Beijing, but from Hebei and Shandong too. An especially vivid example is, in an old Beijing hutong, the onset of the profanity cào is emphatically pronounced as something like [tθ]. However, contrary to your observation, I find more males do this than females. I believe it's a speech impediment much like lisp in English.

Brendan said,

January 14, 2014 @ 11:17 pm

As an addition to Perry Link's questions above, what about "好好儿的" on its own, as in "你要好好儿的" or something of the sort? I think it's got to be hǎohāor in that context, and can't remember ever having heard háohǎor, but all standard non-native speaker disclaimers apply.

Stephan Stiller said,

January 14, 2014 @ 11:17 pm

Not having checked with prescriptive sources about MSM on this matter (as other commenters indicate, they do say something about this), I believe to distill (from the above discussion) a generalization where hǎohāo(r) is endorsed as official as well as actually used by many, with the "spelling pronunciation" hǎohǎo (= háohǎo as the surface pronunciation) unsurprisingly attested elsewhere and on TW, which (for various reasons) is now being recognized as providing its own reference standard. In any case, hǎohǎo (= háohǎo) seems to be accepted by listeners, perhaps because it is a spelling pronunciation. Note though that "I think I've heard that" or "I can imagine someone from X saying this" is not the same as attestation of a variant – but thankfully Grace Wu serves as a clear reference point for us.

@Perry Link

Another example is 小姐, with xiáojie as the surface pronunciation. Note though that there is something going for the theory that tonal change within a word is (often? always?) lexicalized. So while I agree with you pointing out exceptions, one could easily say about them that the statement "tonal change can still apply after neutralization" (opening up a deeper question about phonology) doesn't apply because the changed tonal information is lexicalized. In this particular case, we don't seem to see háohao.

Victor Mair said,

January 15, 2014 @ 12:29 am

From Yao Hui, PRC grad student from Wuhan:

If I use the term in conversation I'll pronounce it hǎohāo xuéxí (I won't say hǎohāor), but if I am reading a text and 好好学习 shows up (especially along with天天向上), I will pronounce it as háohǎo xuéxí.

Stephan Stiller said,

January 15, 2014 @ 5:09 am

Two notes:

1. @ Perry Link

I am skeptical about the hypothesis that tonal change "almost always" applies (even) when the triggering/next syllable is in the neutral tone. I think it's more like that it's the default that it doesn't apply, while the few known exceptions (一个, 小姐 … and?) stand out.

It's very easy to confuse a 2-3 with a 2-0 tone contour. (The third tone is falling-only more often than what textbooks might make one think. But then note that a neutral tone after a second tone is often pronounced like what seems like a clipped high falling tone (making a distinction often easy after all), though I haven't checked whether the origin of the second tone (ie: whether it can be interpreted as deriving from a third tone) matters.) But I could be wrong.

2. Some people expressed that they might pronounce 好好 as hǎohǎo (understood in pinyin orthography to be pronounced háohǎo after obligatory tonal change) if part of the larger saying "好好学习,天天向上".

While I don't know how common this particular variation is in standard Mandarin, there will be a simple explanation: In juxtaposition with 天天 (tiāntiān), saying (the equally reduplicative) 好好 as hǎohǎo will create more parallelism than saying it as hǎohāo, thereby mirroring the identical tones 1-1 in 天天. Of course hǎohǎo is actually háohǎo, but at least it's as parallel as we can make it (because one can never violate the constraint against two successive surface third tones in MSM, unless there's a phrase boundary in the middle). That there is even more parallelism in the whole tonal sequence is like icing on the cake: 3[2]-3-2-2 / 1-1-4-4. Prosody can be mysterious, but here it seems apt.

Victor Mair said,

January 15, 2014 @ 9:49 am

From San Duanmu, who says that this "is a great topic for an experiment. I hope someone would be interested to do one."

======

If you ask me how I pronounce it in my PTH, I'd say 2-3 (rise + low, not rise + fall-rise), but my native dialect is not Beijing. I guess most non-Beijing speakers of PTH would use 2-3.

The question is what do Beijing speakers use, 2-3 or 3-0 (low-high, not low-fall). I think there are two possibilities:

1. 3-0 (hao-hao or hao-haor). This is consistent with a Beijing rule that a common adverbial XXr is usually 3-0 (慢慢儿,好好儿,高高儿,etc.). Non-common XX adjectives or adverbs may still be 2-3 though, such as 满满(一碗饭),久久(不来),老老(的一位长者),仅仅(三个人),紧紧(地关上门)etc.

2. 2-3 (hao-hao). This is the pattern with most other 3-3, such as non-reduplicated A or N (很好,好久,小狗,etc.), or non-XXr reduplicates, such as 想想,走走,小小,etc.

Now, since 3-0 好好儿 is a common expression in Beijing, why do Beijing speakers choose 2-3 at all? There are several reasons. First, there is no 儿 in the written form. Second, the expression is not a colloquial one, but a formal command or expectation. Third, official (public media) PTH uses 儿 and 轻声 less often than Beijing, especially with formal expressions.

Victor Mair said,

January 15, 2014 @ 8:11 pm

From Tsu-Lin Mei:

It occurred to me that “good, good, study” is not something that we say*, and therefore there is so much confusion as to the tone sandhi, or the lack of, associated with this phrase. I am watching CCTV 4 every day and I find the language quite bad. The reporter reads aloud what she has written (and passed censure) and not she wants to say in a natural, colloquial style. When I was teaching at Harvard, there was staff meeting to find out how we would say something, e.g. “study diligently and well”. Perry Link has a book out detailing officialese in China. A few years ago, I think it was in 2005, I saw at Peking University a large banner congratulating XXX Institute for victoriously opened a conference. Does it mean that are bad elements trying to prevent the opening of this conference? Of course, at the end of every conference, the MC would congratulate everyone for victorious completed the task entrusted to them.

Victor victoriously inaugurated the Sino-Platonic Papers.

*[VHM: By that, I'm pretty sure that Tsu-Lin means "we Chinese in the pre-Communist era.]

Stephan Stiller said,

January 15, 2014 @ 11:44 pm

Btw Perry Link's book that Tsu-Lin Mei is referring to is An Anatomy of Chinese, which came out in the beginning of 2013 and which is very high on my reading list! It also talks about prosodic matters (chapter 1, "Rhythm").

Akito said,

January 16, 2014 @ 3:53 am

No expert, merely learning Chinese as a hobby. Could this be the correct derivation of the 3-1 tone sequence for haohao(-r)?

3-3

reduction of second syllable to neutral tone -> 3-0

neutral tone reanalyzed as first tone -> 3-1

(the neutral tone after third tone is relatively high)

A similar process in English is when the "short o" of from, of, what is reduced to schwa and reinterpreted as "short u" in American dialects.

Just a thought.

Akito said,

January 16, 2014 @ 4:24 am

And an afterthought:

The neutral tone was reanalyzed as first tone to reduce the third syllable to neutral tone in haohaorde. Then the 3-1 sequence became fixed as an alternate pronunication even where -r is absent.

Akito said,

January 16, 2014 @ 4:26 am

Even where de is absent. Sumimasen.

Conal Boyce said,

January 16, 2014 @ 9:50 am

I found Yao Hui's remark about speaking vs reading especially interesting. I can't produce an example off-hand, but there must be countless words in English, too, that we say one way in the heat of the moment, yet pronounce quite differently if shown on a piece of paper, to be read aloud (especially if for the benefit of an ESL student, ironically). Two different parts of the brain light up perhaps?

So, for what it's worth, coming from a nonnative speaker, when speaking I would say hao3hao1.de or — if in a BJ milieu — perhaps even "haohaol(.de)" referring back to Tsu-lin Mei's post that references Y.R.Chao & Iris Pian (wonderful trip there down memory lane, all the way back to 1957[!], those rich quirky voices of father and daughter, engraved forever on one's mind).

Victor Mair said,

January 16, 2014 @ 9:57 am

From a long-term resident in Taiwan:

Among people who grew up in Taiwan, it would normally be 2-3-2-2. 'Normal' means as opposed to jocular or pretentious. A minority of people around my age who grew up in 眷村 might say 3-1-2-2.

I have never noticed anyone say 天天向上.

Daniel Tse said,

January 17, 2014 @ 4:15 am

@Victor Mair: If the award is divisible, I humbly accept half ;)

frog from well said,

February 27, 2014 @ 9:36 am

hao3 hao0 xue2 xi2, hao2 hao3 xue2 xi2

Victor Mair is right, both correct.