On swallowing and slurring in Pekingese

« previous post | next post »

I called this old post to the attention of Yijie Zhang, a true native of Peking / Beijing / Beizhing:

"How they say 'Beijing' in Beijing" (8/18/08)

Yijie's reply:

I totally agree with you! There is indeed an enormous amount of slurring and swallowing of consonants in Pekingese, which is sometimes referred to as "tūn zìr 吞字儿" ("swallowing characters") or "tūn yīn 吞音" ("swallow sounds"). As a native Běijīng rén 北京人 ("Pekingese"), I remember a friend of mine from Jiangsu province once complained that it almost sounded like a trisyllabic word when I was saying a five-character phrase, and she always had to guess what I was saying (according to the vowel contours) because of my "tūn yīn 吞音" ("swallowing the sounds"). Other topolect speakers enumerated some of the most typical words of "tūn yīn 吞音" ("swallowing the sounds") in Pekingese:

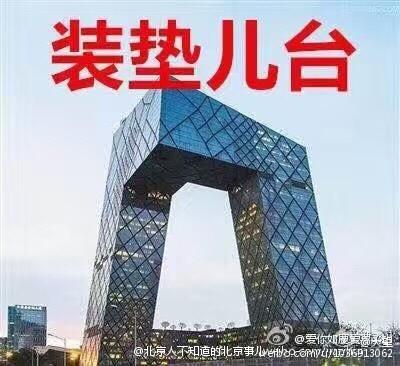

Zhuāng diànr tái 装垫儿台 ("padded / cushion station") for Zhōngyāng diànshì tái 中央电视台 ("CCTV")

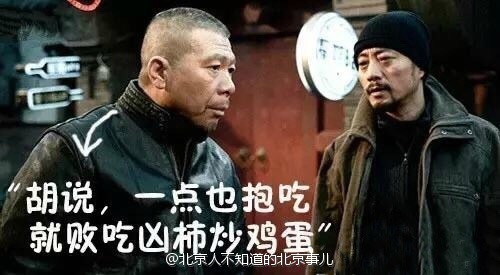

"Húshuō, yīdiǎn yě bào chī, jiù bài chī xiōng shì chǎo jīdàn 胡说,一点也抱吃,就败吃凶柿炒鸡蛋 ("Nonsense, I've eaten a little full; just fail to eat fierce persimmons with scrambled eggs") for "Húshuō, yīdiǎn yě bù h ǎochī, jiù bù ài chī xīhóngshì chǎo jīdàn 胡说,一点也不好吃,就不爱吃西红柿炒鸡蛋" (" Nonsense, not good at all, I don’t like to eat tomatoes with scrambled eggs")

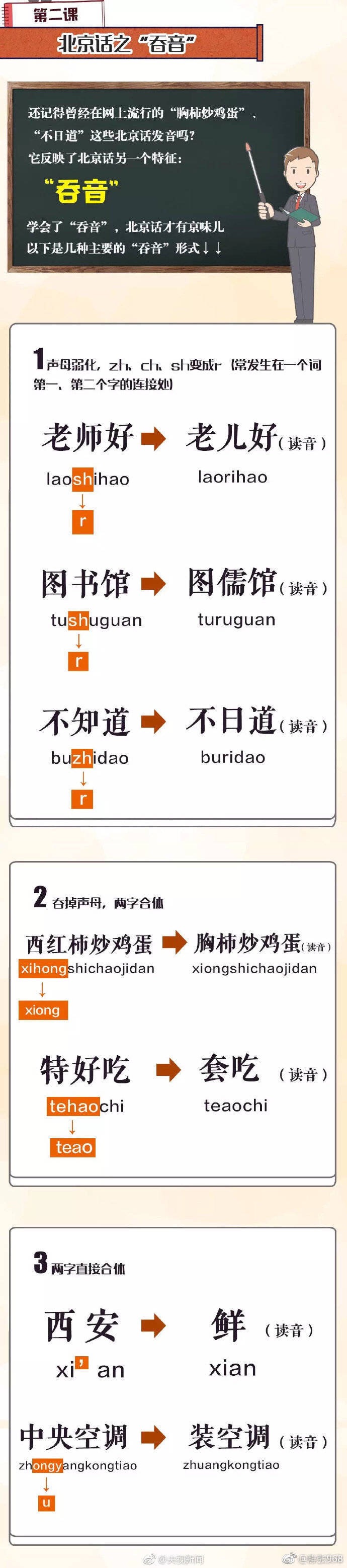

Some even summarized the basic rules:

[VHM; Since the characters and Romanizations are given, I will only provide the English translations for the six example pairs that were not covered above:

1. "Hello, teacher." "Hello, old man."

2. library illustrated Confucian hall

3. don't know not day way

4. especially tasty set for eating

5. Xi'an fresh

6. central air conditioning install air conditioning]

Basically, 1. most of the medial consonants beginning the second syllable of bisyllabic or trisyllabic words are weakened, and sometimes "zh", "ch" and "sh" / the IPA [ʈʂ],[ʈʂʰ] and [ʂ] are replaced by an "r" sound following the first syllable; 2. "h" / the IPA [x] beginning the second syllable of a word is sometimes elided and thus the first and second syllables are "combined as one"; 3. the second syllable of a word without a consonant or the second syllable with "y" / the IPA [j] as its consonant are sometimes blurred and become a glide.

In speaking of "j", "q" and "x" (the IPA [tɕ], [tɕʰ] and [ɕ]), I feel like they are weakened more often as the second syllable of trisyllabic words than bisyllabic words

And unless I enunciate conscientiously on purpose, "大家好" would never come out sounding like “dà jiā hǎo”, rather, it always comes out like "dà-yā hǎo" (I wish I could say these words from my mouth since typing is kind of limiting in this circumstance :D).

Added notes by David Moser:

Because the initial in "jing" is not a retroflex, "Beijing" in ordinary rapid speech still tends to retain an auditory trace, but yes, it seems to me that in very rapid, slurring speech (e.g. Beijing cab driver) the word "Beijing dianshitai" does sound like "Bei (y)ing dianr tai".

By the way, I was noticing just the other day that we English speakers not only say "Whaddya wanna do?" for "What do you want to do?", but we also sometimes slur it even more into "Wha' ya wanna do?" There are degrees of slurriness.

VHM: And then there's the famous example of "What's up?" –> "'sup?"

Readings

"OMG moments induced by allegro forms in Pekingese" (1/26/12)

"Surprising Transformations of a Beijing Street Name" (1/29/11)

other one spoon said,

May 3, 2019 @ 12:28 pm

As a friend from London once asked me, "Jur ched?"

This translated as, "Did you hurt your head?" When it comes to swallowing sounds in English, the London accent is probably a strong contender for top prize.

Arthur waldron said,

May 3, 2019 @ 12:36 pm

In America all foreign words are pronounced as if they were

French. In England as they were Received Pronunciation.

Arthur

Ross Presser said,

May 3, 2019 @ 1:14 pm

In Philadelphia we also famously have "jawn", which purportedly evolved from "joint" in New York dialect.

And there's the widespread American "A'ight?" which represents "All right?"

Going way back to the 70s, my mother used to be amused by "Jeet yet? No, ju?" (Did you eat yet? No, did you?)

Ross Presser said,

May 3, 2019 @ 1:16 pm

And another is "Nome sane?" (Know what I'm saying?)

Trogluddite said,

May 3, 2019 @ 4:32 pm

A few of my favourites reputedly from around here in Yorkshire, though somewhat more widespread in reality, I suspect…

"Supwier?" – What it up with you?

"Tintintin" – It cannot be found in the metal container.

"Nobbut" – Nothing but (via "nowt but".)

Some local place names can be fun like that too, and not necessarily in clipped speech. If someone tells you they're from "Aptrick" or "Barlick", they mean Appletreewick or Barnoldswick.

RfP said,

May 3, 2019 @ 7:32 pm

I’ve been told that Samancisco—California’s City By The Bay—is often referred to as Sampancho by Spanish-speaking locals.

And our great newspaper columnist of the mid-20th century, Herb Caen, sometimes styled himself as the Sackamenna kid, coming as he did from the state capital.

B.Ma said,

May 4, 2019 @ 12:53 am

I'm not sure of the value of translating things like "Nonsense, I've eaten a little full; just fail to eat fierce persimmons with scrambled eggs" since the characters involved are simply used for their sounds. 先 could just as well have been used for the slurred representation of Xi'an.

David Marjanović said,

May 4, 2019 @ 5:28 am

See also: Trahno, Can'da.

Philip Taylor said,

May 4, 2019 @ 6:55 am

I used to pass through "Trahno" on my way to Guelph, Waterloo & Kitchener quite frequently, but used to hear it more as /ˈtrɒ-nə/.

Julian said,

May 4, 2019 @ 7:01 am

Mark Twain, in his memoir of Australia and New Zealand (1897), describes how a well bred Australian, if you give them something, will say, 'Q.' To which you should answer, 'Cm.'

Victor Mair said,

May 4, 2019 @ 7:01 am

"Nonsense, I've eaten a little full; just fail to eat fierce persimmons with scrambled eggs"

1. I provide such translations for those who have zero understanding of the meaning of Chinese characters and are curious about what the characters used for such transcriptions signify.

2. Those transcriptions do partially convey some silly ideas, and the people who make them up are quite aware of that, as are the people in China who read them.. They are not just sounds without any meaning whatsoever. That's what makes them all the funnier.

Language Log readers have often told me how they appreciate my efforts to make my posts accessible to those who do not know any Chinese. To suggest that there is no value in my efforts is being trollish.

R. Fenwick said,

May 4, 2019 @ 9:17 pm

@other one spoon:

When it comes to swallowing sounds in English, the London accent is probably a strong contender for top prize.

I don't know, broad Australian (or, in broad Australian, "Strine") could probably give it a rock solid contest.

"Jegoda the footy?" "Nar, dingo – sorten TV."

"Emma chisit?" "Threem form smite."

"Leasher kemput the egg nishner on."

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strine

Ouen said,

May 5, 2019 @ 5:02 am

Does the contraction of 不要 to 嫑 (pronounced biao) originate in Beijing? How common is it in Beijing for people to actually type the character 嫑

It’s just a character a came across in a dictionary and I haven’t met a native speaker who uses it as of yet

Mark Liberman said,

May 5, 2019 @ 3:15 pm

Among linguists, this sort of "swallowing and slurring" is known as "sound change".

Jerry Packard said,

May 6, 2019 @ 7:03 am

@Mark Liberman

I love it.

Jonathan Smith said,

May 6, 2019 @ 9:31 am

Re: sound change — yes and in some of these cases the above impressionistic naive and/or prescriptive accounts may be all we have. For example, "túshūguǎn > túrūguǎn" is capturing something real, but it's both unclear (to me) that this is a precise description of the change involved and certain that the process is paralleled in onsets from different manner series.

Incidentally word-internal changes of this kind cause problems in historical studies because the focus there tends to be on the morphosyllable/"character". So wrt other Sinitic varieties we definitely have the equivalent of claiming for the above case that "rū is 'book' in native Pekingese while shū is a literary intrusion" or indeed further "PK 'book' is rū while 'deep' is shēn both of which correspond to Middle Chinese ɕ- thus [surprising conclusion about historical Chinese]."

Chris Button said,

May 7, 2019 @ 8:15 pm

@ Jonathan Smith

The phonological change is pretty easy to identify. You can essentially treat zh, ch, sh and j, q, x as the same sound just with an r or y component respectively. In rapid speech, all that is left is that approximant component.

That would be like divorcing the assimilated "im" or "il" sounds in "impossible" and "illogical" from their original "in" form.

Jonathan Smith said,

May 8, 2019 @ 10:58 am

@ Chris Button

I mean that "túrūguǎn" and others are just eye dialect awaiting considered analyses; you could do lots of things but real data would be good first… i.e., does this process really yield perceptual minimal pairs with (something like) [r] resulting from /ʃ/ and /r/? Is it really (strictly) a "rapid speech" phenomenon? People speak Mandarin fast in many places but this change AFAIK is characteristic of Beijing… perhaps the "apical" vowels are actually phonetically rhotic (?) there not elsewhere, which might allow an analyses something like yours to work? Does this change involve aspirates /tʃʰ/, etc., as you imply? Surely not? And as I said my sense is that there are parallel cases which make it tempting to invoke something more general like "intervocalic voicing"… etc.

Re: "That would be like divorcing the assimilated 'im' or 'il' sounds in 'impossible' and 'illogical' from their original 'in' form" — yes, quite like that. For early Chinese, where you can pretend almost usefully that words are monosyllabic, there is perhaps less of a problem here, but for anything post-Han-ish, focus on the "character" level can be disastrously misleading.

Chas Belov said,

May 11, 2019 @ 5:36 pm

San Franciscan here. When I'm not calling it "The City" or, jocularly, "the west bay" (to placate Oaklanders and Berkeleyites who object to "the east bay"), I pronounce it approximately "Samfancisco." In Cantonese it's Sàam Faahn Síh 三藩市(three-wall city), which I find particularly clever.