Surprising Transformations of a Beijing Street Name

« previous post | next post »

In a recent LL post, I wrote about Northeast and Northwest Mandarin borrowings from Russian that — in the mouths of those who are not highly literate in characters — seem to have escaped the phonotactic constraints of the sinographic script. In this post, I write about a Beijing street name that began as a sinographically writable expression, but which — again in the mouths of those whose speech is not strongly conditioned by the characters — devolved into a form that cannot readily be written in characters.

We start with the book form of the name: 大柵欄. The "proper," Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) pronunciation of this name should be Dà Zhàlán, which means "Big Paling(s) / Railing(s) / Bars." This is the name of one of the oldest commercial streets in Beijing, which lies in the Qianmen ("Front Gate") district to the southwest of Tian'anmen (Gate of Heavenly Peace — made especially famous by the events of June 4, 1989).

Some years ago, probably about ten, I set out to find this street and its hutongs (alleys) about which I had heard so much. Armed with a map, and already knowing my way around Beijing fairly well, I headed in the direction of Dà Zhàlán. When I got near where I thought it should be, I began to ask the people on the street, "Qǐngwèn, Dà Zhàlán zài nǎr?" 請問,大柵欄在哪儿 ("Please tell me where Dà Zhàlán is"). Every single person looked at me uncomprehendingly, even though I very carefully and deliberately enunciated my question in the best MSM I could muster. After about 20 minutes of circling around in the area where I knew the street must be, I became more and more frustrated. My failure to find Dà Zhàlán was particularly galling, inasmuch as I had prepared so thoroughly for finding it (bringing a map, reconnoitering the area, making sure I knew how to pronounce the characters with the proper tones, being careful to say nǎr 哪儿 ["where," with the Pekingese retroflex ending, instead of MSM nǎlǐ 哪裡], and so on).

At my wit's end, and surmising from all of my focused wanderings through the hutongs that I must already have been on Dà Zhàlán street for some time, I decided to change my tactic. So the next person I met, who looked like a real local who surely ought to know, I asked, "Qǐngwèn, zhè tiáo jiē jiào shénme míngzì?“ 請問,這條街叫甚麼名字? ("Please tell me the name of this street.") The answer I received almost made me keel over: "Dashlar!" Whereupon I mentioned that I was looking for Dà Zhàlán street — enunciating very carefully and with restrained exasperation, to which my interlocutor replied, "I don't know where that street is, but this is Dashlar."

Finally, I saw a couple of Americans and went over to ask them where Dà Zhàlán street was, to which they replied, "You're on it."

How did this happen? How did Dà Zhàlán become Dashlar?

The main problem lies with the second syllable. For some reason, the local Beijingers don't want to be troubled to articulate zhà as is when it is sandwiched between dà and lán. The phonological transformations of the name seem to have proceeded thus: Dà Zhàlán –> Dà Shàlán –> Dàshílàn / Dàshilàn –> Dàshílànr / Dàshilànr –> Dashlar.

Here is the name as pronounced by a highly character-literate Beijinger:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

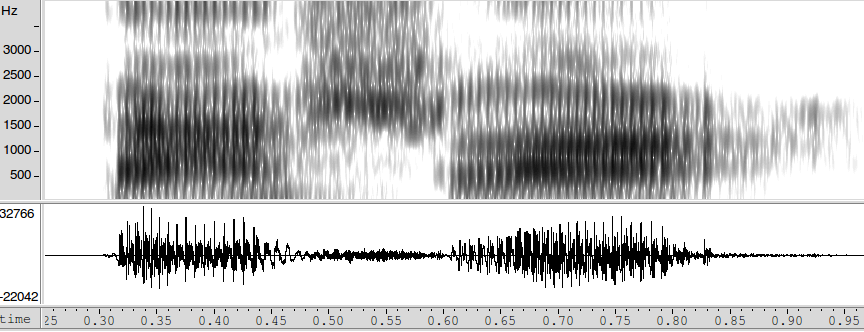

The person who spoke this would romanize it thus: Dàshilànr. But I can barely hear the [i] after the [ʃ], If it's there, it's present only as a somewhat elongated (140 msec.) [ʃ] segment, a tiny (15 msec.) voiceless [i] that is hardly distinguishable from the inevitable transition between [ʃ] and [l], and perhaps a pitch contour a bit different from what would unexpected in a true disyllable. This is same sort of process of high-vowel devoicing and assimilation to a preceding fricative which creates the typical Japanese pronunciation of e.g. "sukiyaki", where the first two syllables become [ski], with the only evidence of the /u/ vowel being an elongated [s] and a moral commitment to the lack of consonant clusters.

Here's a spectrogram of the above pronunciation of Dà Zhàlán, illustrating the point:

I'm certain that I didn't hear even that ghost of the -i sound after the sh- when it was spoken to me on the street: Dashlar!

Such phonological transformations are profuse in Pekingese speech, making it very difficult for outsiders to understand what the locals are saying. The permutations of Gē'ermen 哥儿们 ("brothers, buddies, pals…"), for example, in increasingly less formal levels of speech, all the way down to gangster talk, are truly astonishing. And that's not even to broach the matter of unique lexical items in Pekingese, which are totally opaque to all but native speakers of the colloquial language (e.g., cuibenr ["toady, sycophant"].

In fact, in all of the many varieties of Mandarin, the phonological expectations embodied in the writing system seem to have a much stronger effect on speech perception than on speech production. That is, native speakers produce all sorts of phonologically interesting forms which literate native listeners have a very hard time hearing. As a result, these phenomena have been much less widely documented and studied than might be expected, given how striking they are to learners. The widespread lenition and even deletion of the medial consonant in two-syllable words is another example. Presumably the failure to hear such things is related to the well-known phoneme restoration effect.

[Thanks are due to Jing Wen and Zhao Lu]

Twitter Trackbacks for Language Log » Surprising Transformations of a Beijing Street Name [upenn.edu] on Topsy.com said,

January 29, 2011 @ 8:03 am

[…] Language Log » Surprising Transformations of a Beijing Street Name languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2931 – view page – cached January 29, 2011 @ 6:59 am · Filed by Victor Mair under Phonetics and phonology, Writing Systems […]

mondain said,

January 29, 2011 @ 9:43 am

I tried to locate Dashlar in a recording of 侯宝林 (Youtube at 6:07; WAV), which sounds to me with more stress on [ʃ].

Chris Slaby said,

January 29, 2011 @ 9:46 am

I'm curious as to what the "official" Chinese position on this would be. In the past Professor Mair has written about certain government officials speaking out against foreign/Western/non-Chinese influences on the Chinese language. Seeing as these non-standard (phonologically) words do exist, what do those same Chinese officials make of this? Do they acknowledge the existence of such words? Do the take what would basically be a prescriptive approach and denounce such words as inappropriate/ungrammatical/wrong? I guess I'm wondering if there is a sense, at least among some, of linguistic nationalism, which in this case includes a sense of phonological purity.

Stu said,

January 29, 2011 @ 11:00 am

It's interesting that you mention the Japanese example of 'sukiyaki.' I spent a lot of time in Kyoto and Tokyo during college, where (although suki desu was always pronounced as 'ski') 'sukiyaki' was always very clearly pronounced 'su-ki-ya-ki.' However, my girlfriend, who learned what japanese she knows from her Ishikawa-born father, refuses to pronounce it as anything other than 'skiyaki.'

We've done informal polls with others (as this is a longstanding topic of conversation with us), and, very unscientifically, it seems that the people who are most likely to say 'skiyaki' tend to be from more rural areas, whereas the various edokko tend to say 'sukiyaki.'

Yao Ziyuan said,

January 29, 2011 @ 11:19 am

The non-standard phonological features you hear in colloquial Chinese speech are certainly created by the Chinese people in their daily work and life over time. Chairman Mao famously said: "The people's wisdom is infinite." The people tend to set language free, simplifying characters and speech to suite their daily needs, while political authorities over history tend to standardize language usages and even complicate characters so that they can make more people illiterate and foolish.

Victor Mair said,

January 29, 2011 @ 11:45 am

Jianhua Bai reminded of something that I've often noticed on the streets of Beijing. Instead of saying bùzhīdào 不知道 ("I don't know"), real Beijingers ("Lao Beijing" 老北京) say BURDAO, with the retroflex -R- sneaking in between the first and last syllables (it is usually attached to the end of words in which it appears).

The level of casualness in BURDAO is comparable to that in English "dunno" for standard "I don't know," or, even more properly, "I do not know."

Mark Mandel said,

January 29, 2011 @ 11:58 am

For those readers even less familiar with Mandarin than I am: the change of /zhī/ to /-r/ is not as bizarre as it might look. /zh/ is a voiceless retroflex affricate, and IIRC* the phoneme symbol /i/ in this context is a retroflex vowel, IPA [ʅ] (U+0285), to which /-r/ is the corresponding off-glide.

* and I'm sure I'll be corrected if not

Mark Mandel said,

January 29, 2011 @ 11:59 am

Oops, make that "unaspirated" instead of "voiceless".

Hermann Burchard said,

January 29, 2011 @ 1:30 pm

Victor Mair's "dunno" example reminds me of my 1970 experience with the Bloomington IU housing manager, when a clutch of baby mice in the wall had died in my rental house, an unhappy and smelly situation. He explained to me how a wall is built, new to this immigrant, and that it has a structural element called a "toob'foe" — very patiently repeating the word several times the only way he could pronounce it until I understood "two-by-four." Not clear to me now how it was possible that I actually understood the concept never having heard anybody say the word before.

maidhc said,

January 29, 2011 @ 5:36 pm

@Hermann Burchard

I've heard that Italian-speaking construction workers in Toronto, who were of course brought up on metric units, created a new Italian word "tubafora".

Victor Mair said,

January 29, 2011 @ 8:21 pm

From a German friend:

Although I don't, of course, understand any Chinese, somehow this story reminds me of a curious situation I encountered in Bavaria. And just like not understanding Chinese, I am not sure how to spell out this Bavarian situation (including not having an Umlaut icon on this P/C). For about a year I went to school in Eichstaett (roughly betw. Munich & Nuernberg). As the only Protestant in a Catholic convent was an interesting experience – in more ways than one. Always curious, I would ask when some word in dialect was unrecognisable. The girls always used the same greeting(s), rather like we might say "bye" or ciao or "seeya", something quite short and quick. I'm a bit at a loss if I can manage to put this word into letters – "Pfueady" (the ue representing the Umlaut) The Pf was always pronounced very strongly, like a strong blowing sound, and the U Umlaut and following A were clear, distinct syllables. I puzzled over this for some time and finally asked one of the least religious appearing outside teachers (i.e., not nuns as most were) and was told the greeting was a contraction of the Catholic blessing "behuet dich Gott".

Before television, Germany used to have some rather interesting, colorful and odd dialects, most of which, however, one was able to unpuzzle eventually. But this Bavarian greeting still has me stumped. And now writing it down for the first time, it looks even more peculiar. There is no logical way to find a basic word derivative, either in the letters nor what the ear perceives.

Since the advent of TV only those raised before still speak dialect, often in a "diluted" form. Do you find that not also the case in China?

Of course we spoke only "High German", although in school I would "berliner" with my classmates". But my father had us often engaged in every possible dialect so that I could pretty much tell, within about 50 Km, where people were from. Now one cannot even detect the slightest of inflection.

VHM: If you Google on / pfüati / and / pfüat di meaning /, you'll find explanations of the Bavarian term my friend is talking about.

Hermann Burchard said,

January 29, 2011 @ 11:32 pm

About one hundred and fifty years ago, educated North Germans often spoke French. The said "Adieu" when parting, which later became "Tschuess" (Tschüß) .

Admit that I did not recall origin of "pfüati" before seeing it explained, although dialects in Bavaria and Tirol are very similar, and as a kid we stayed in Tirol from '40 to '42. Playing out in the street, my sister and I learnt to speak "Tirolerisch" fluently within weeks. Even now, I still can pronounce Tirolian accent free. Back in the hotel we spoke High German. Still, everybody knew we were from North Germany, so they called us "Sau-Preissen" or "Pig Prussians" in memory of trouble in the 1860s, even though we were from Hamburg. In every other respect they treated us kindly.

Allegedly we went because of my brother's tuberculosis, but in reality to hide, because of non-Aryan descent (my guess). It was a big help that my dad was from an influential family. He moved us from one rural area to another when on furlough. As a result, I changed grade school six times by '45. After '43 he served at home, having been wounded multiple times. He was a medic and never fired a shot. In '45, he and his oldest brother were involved in the surrender of Hamburg to the British without fighting.

Fluxor said,

January 29, 2011 @ 11:54 pm

Here's a quote from zdic.net:

栅 shi

◎ 〔大~栏〕方言,中国北京市前门外一条热闹街市名。

Seems pretty well documented. 栅(柵) can also be pronounced as shan1 or shan4. In fact, this usage is quite common in my line of work to refer to logic gates or gate terminals of transistors. It's not hard to see how "shi" might have evolved from shan1/shan4. Granted, when used with 欄 as in 柵欄, 柵 is supposed to be pronounced as zha4. But it may just be a differene between la1ji1 and le4se4. Language committees simply chose different variants as the standard.

As for BURDAO, I don't think it's a retroflex 'r' sneaking in there, rather, it's the retroflex 'r' remaining in place after contracted speech. Perhaps the pinyin spelling is confusing the issue. The 知 (zhi1) in 不知道 is pronounced with the retroflex. Dropping the "zh" in "zhi1", as may happen during contracted speech, changes the pronunciation to "ri1". Thus, BUZHIDAO becomes BURDAO.

Hermann Burchard said,

January 30, 2011 @ 12:17 am

@maidhc

Italian "tubafora" with a melodious four syllables, of course. While "toob'foe" is 1.5 syllables, the "foe" almost toneless, not much more than a schwa. Does anybody know where the Italian got their musical speech? From the Lombards? Originally they were from Sweden, famous for its melodious tonal language.

Peter G. Howland said,

January 30, 2011 @ 3:53 am

words to work by

As Yao Ziyuan pointed out above, people often simplify the phonetic features of speech to suit the needs of their daily work. And it seems that the more common a term is, the more likely it is to change into something that has escaped the phonological constraints of strict orthographic representation.

“Put that two-bah-tin own toppa that stakka tubahforz.”

(Put that two-by-ten on top of that stack of two-by-fours)

“They’s tubefor studs under that four-buh-ate.”

(There are two-by-four studs under that four-by-eight)

On any given construction site there will be hundreds of two-by-fours of various lengths used throughout the work, but only a small number of the larger sizes, typically used for headers, beams, etc., on hand. I’ve observed that when the less commonly used materials are referred to, their size designations are far more likely to be enunciated with a degree clarity.

BTW, loved the Italian “tubafora”…especially when I said it aloud several times in a so-called “Italian” accent. Perfect! Reminds me of the Mexican “drywalleros” I used to hear about on job sites in Southern California, an appellation used without hesitation by Spanish-speaking contractors to designate their workers who installed dry wall. Need a word? Make one up!

Marc said,

January 30, 2011 @ 2:50 pm

Stu, in almost all Kansai dialects 好き is pronounced with an accent on the す, and the /u/ is very audible. The situation with すき焼き is slightly different, because there are more syllables, but you can still hear the /u/ in the first syllable in some Kansai dialect speakers' speech.

It's not an urban/rural division.

Mary Kuhner said,

January 31, 2011 @ 4:18 am

English, it seems to me, encounters this with slang terms that have a stop in them, like the Simpsons' "d'oh" or the reduced form of "no" usually spelled "unh-uh." There is really no consensus way to write this sound, but native-born slang words have it. How strange is that?!

I remember the Internet struggling with how to write "d'oh" once people started to say it. I ended up learning a spoken-only word and a written-only word, and not connecting them together for a couple of years, because not a single one of the myriad alternative spellings communicated the stop to me.

Marc said,

February 1, 2011 @ 1:37 am

The glottal stop is American English's dirty secret. It's used as much as in Hawaiian or Arabic, but no textbook (that I've seen) teaches it. A sentence like "Witten wouldn't want Weatherford to punt one" has five of them. It's the reason "shipmate" is pronounced identically to "shit-mate."

But of course, English doesn't do spelling reform (only alphabetic language in the world with spelling bees: symbol of brokenness of English spelling, not something to be proud of ("Our spelling system is so stupidly unworkable we celebrate people who can spell! Yay!")), so don't hold your breath for any changes that would reflect how we actually speak our language…

Victor Mair said,

February 1, 2011 @ 10:57 am

The Turkologist, Peter Golden, notes: "It almost sounds like Azeri Turkish dashlar (stones, rocks, tashlar in Modern Turkish and most Turkic languages; -lar is the plural marker), but that, of course, is quite impossible."

To which I replied:

I felt all along that it *sounded* so Altaic. But, as you say, Peter, since the Chinese name is supposed to signify Big Railings / Bars, it would seem impossible that it could come from Turkic. However, it is very interesting that, upon reading my blog on Dashlar, a distinguished scholar of Sino-Tibetan (Robert S. Bauer) wrote the following to me:

====

I think what you have discovered is that deeply underlying Peking dialect is a strongly non-Han language base.

====

The late Mantaro Hashimoto and Charles Li, as well as others like David Branner, all feel that Mandarin was strongly influenced by Altaic languages in all respects (phonology, lexicon, grammar). In this case, the phonological shape of Dashlar resembles Turkic languages more than it does Sinitic.

Victor Mair said,

February 1, 2011 @ 11:01 am

Sarang said:

I assume the resemblance between "ashlar" and "dashlar" is entirely coincidental?

Ken Brown said,

February 1, 2011 @ 1:20 pm

@Marc, if we reformed our spelling to include glottal stops, we'd all have to put them in different places. Like "glottal". And then you'd get mad when we took all your Rs away.

Marc said,

February 1, 2011 @ 1:47 pm

Ken, good point. There's still room for improvement (and compromise). :)

As for Mandarin, if there were an underlying Altaic base to Mandarin, wouldn't it go from more obvious to less obvious as time passes?

Ron said,

February 1, 2011 @ 2:07 pm

"a moral commitment to the lack of consonant clusters" made me smile. It definitely belongs on a t-shirt.

I don't speak Mandarin and my Japanese is extremely rusty but I really enjoy your posts.

Gilbert Roy said,

February 5, 2011 @ 1:03 pm

The permutations of Gē'ermen 哥儿们 ?? – speaking of permutations, I have long used 哥们儿 with (male) friends in North China.

RE: Altaicization: I have contended for several decades that Mandarin verbs "assimilated" Altaic (specifically Mongol) verb suffix system during the relatively short span of the (Mongol) Yuan dynasty, i.e. beginning in the 13th century. I suppose the opposite phenomenon is possible,as offered by Bauer, that there is a "non-Han" language system underlying the tons of Han vocabulary???

Britta said,

March 22, 2011 @ 5:21 pm

There is also the Beijing dialect term spelled in standard pinyin "kong-er" 空儿 (colloquial term for "free time") but pronounced more like "ker" (but with a nasalized shua, which I can't do on this keyboard). When I was learning Mandarin in school, this pronunciation was listed as standard in the textbooks, though our teachers told us to just say "kong." The first time I was in China on a study abroad program in Beijing, I used the term in a hutong, and everyone within hearing distance cracked up laughing at the foreigner speaking in Pekingese.