ALT-DAIGO

« previous post | next post »

[This is a guest post by Nathan Hopson]

I live in the central Japanese industrial hub of Nagoya, the city that Toyota (re)built. Despite the greater Nagoya metro area's twelve million inhabitants and a GDP trailing Switzerland for #20 on the world country rankings, the locals in particular refer to the city as inaka, the boonies. Nagoya is a city almost universally described as, "not much to visit, but a nice place to live."

One of the nice quotidian things about living in Nagoya is its cafés' take on the "morning set" (mōningu, to the locals). Usually available from opening until about 11:00am, the Nagoya mōningu is a cheap, simple, and delightful breakfast. Order a regularly priced drink (usually coffee or tea), and it comes with a hardboiled egg and toast. Toast options generally include butter, cinnamon, chocolate, and a particularly Nagoya favorite, adzuki jam—often an extra \100, roughly the commonsense equivalent of a dollar. Known generally as anko, the jam made from adzuki beans comes in the proverbial smooth and chunky varieties familiar to anyone who has ever plunged a tablespoon into a jar of peanut butter. Nagoya, which is proud of its distinct regional cuisine, prefers the chunky kind known as ogura. Toast with adzuki jam is known as ogura tōsuto, or "ogre toast" around my house.

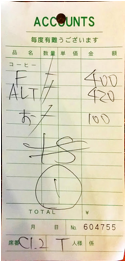

The local mōningu, with or without ogres, has become a Sunday morning tradition for my kids and me. Last week, I took my daughter. I ordered a coffee and ogura toast. She ordered iced lemon tea and cinnamon toast. When we got up to leave, I looked at our check, something I don't ordinarily do, since I know the mōningu menu and prices pretty much by heart now (\400 for my coffee, \100 for the ogura, etc.) I am glad I did. My coffee, a French roast, was labeled "F," my extra order of ogura with the hiragana お (o). It was my daughter's order that really caught my eye, though. "ALT." In common parlance here in Japan, and in East Asia more generally if I am not mistaken, this acronym refers to the hordes of (mostly Anglophone) "Assistant Language Teachers" who teach in primary and secondary schools as well as private language schools throughout the region. And besides, my daughter had ordered an "ILT."

The local mōningu, with or without ogres, has become a Sunday morning tradition for my kids and me. Last week, I took my daughter. I ordered a coffee and ogura toast. She ordered iced lemon tea and cinnamon toast. When we got up to leave, I looked at our check, something I don't ordinarily do, since I know the mōningu menu and prices pretty much by heart now (\400 for my coffee, \100 for the ogura, etc.) I am glad I did. My coffee, a French roast, was labeled "F," my extra order of ogura with the hiragana お (o). It was my daughter's order that really caught my eye, though. "ALT." In common parlance here in Japan, and in East Asia more generally if I am not mistaken, this acronym refers to the hordes of (mostly Anglophone) "Assistant Language Teachers" who teach in primary and secondary schools as well as private language schools throughout the region. And besides, my daughter had ordered an "ILT."

But of course, she hadn't. She had ordered an aisu lemon tī. Ergo, an ALT.

All this reminded me that when I first set about learning to read Japanese in earnest, I struggled with and was fascinated by the way the language handles acronyms and abbreviations. For example, where English abbreviates the United Nations to UN, Japanese goes with 国連 (Kokuren), taking the first kanji from 国際 (kokusai; international) and 連合 (rengō; alliance or association). I work at Nagoya University (名 古屋大学), shortened to Meidai (名 大) in conversation because the first kanji is read both na and mei. This kind of shortening permeates the language; as a translator, my deadlines were often ASAP (naru haya, an abbreviation of なるべく早く narubeku hayaku).

Reading and watching the news in Japanese, I quickly realized that the UN is something of an exception and that the media handle the alphabet soup of international organizations by giving the English acronym along with its Japanese translation the first time, and then simply using the English acronym thereafter. So the World Health Organization becomes WHO (世界保健機関), and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization is NATO (北大西洋条約機構). In conversation, many of these well-known bodies are simply referred to by their English acronyms; even the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (連合国総司令部) is just called GHQ.

This phenomenon, which is a great example of the flexibility of the Japanese language, has recently been taken to an extreme by the Japanese musician and personality known as DAIGO, who is incidentally also the grandson of former Prime Minister Takeshita Noboru. His unique take on abbreviation is called "DAI語." The pronunciation of this coinage is the same as his name; the last character means "language."

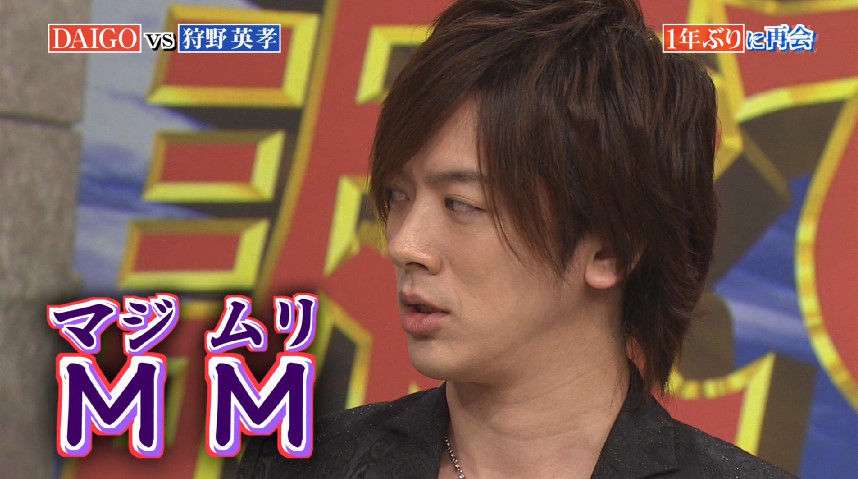

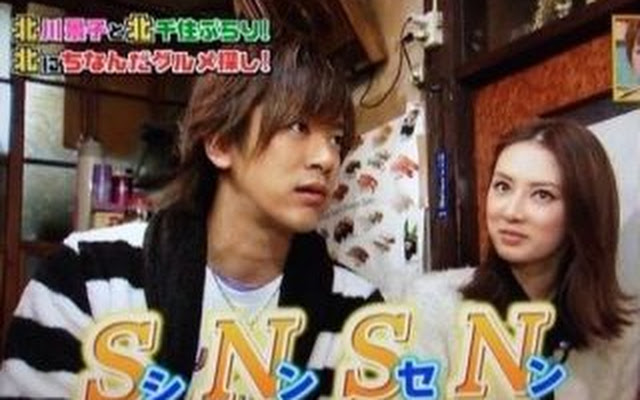

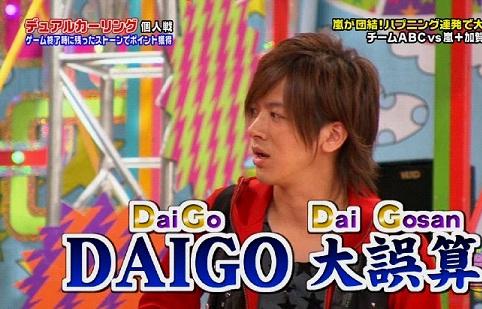

So what is this strange new tongue? This is best explained with a few TV stills. It's first worth noting that Japanese TV tends to be very textually rich, with the screen populated by an enormous amount of written data. This is especially true for the news and for comedy, which often both depend a great deal on what is being said. The titles—interestingly still called "telop (テ ロップ)" after the television opaque projector developed in 1949—have provided program directors with fabulous opportunities for communicating extra messages, many of which take advantage of the particular characteristics of the Japanese language in clever and informative ways. Glosses over characters are used in many different ways, including to enhance the richness of humor, as seen below.

In the first still, DAIGO is saying, "MM," which has been helpfully glossed as マジムリ (maji muri). ムリ (or 無 理 in kanji) means something like, "No way!" and the マ ジ is an intensifier meaning "seriously." In the second picture, he goes one step further: "SNSN" is glossed as shinsen (新 鮮; "fresh"). Below, "DGDG" is read as "Daigo no dai gosan" (DAIGOの 大誤算), or "DAIGO's big miscalculation."

Some of his other creations include:

| SKSG | 試行錯誤 | Shikō sakugo | Trial and error |

| DKB | 大好物 | Dai kōbutsu | One's favorite food |

| KWI | 恐い | Kowai | Scary |

| GGDD | 言語道断 | Gongo dōdan | Outrageous, preposterous |

| OYSM | おやすみ | Oyasumi | Good night |

But DAI語 is not just for DAIGO. Anyone can take a stab, and increasingly others are. As DAIGO himself said, "GIGS" (郷 に入りては郷に従え gō ni ireba gō ni shitagae), or "When in Rome…" In the last photo, model Rola is speaking with DAIGO, and speaking to him "MTM," or "man to man" (man tsū man).

DAI語 is playful, can easily work as in-group argot, and is eminently suited to a world of electronic input and 140-character limits. DAI語 appeals to the same sense of linguistic creativity and improvisational virtuosity that gave us everything from Japanese linked verse to rap. The popularity of DAI語 might ultimately turn out to be little more than a flash in the pan (RTDB 竜頭蛇尾 ryūtō dabi). But his fifteen minutes in the spotlight could leave a mark on the language for years to come. If it does, it will be because DAIGO's inventiveness draws heavily on a pantheon of abbreviation techniques, a tradition of linguistic glossing and multiple meanings hidden in homophony, and a quotidian culture in which iced lemon tea is ALT.

tsts said,

March 26, 2016 @ 4:26 pm

"Despite two and a quarter million inhabitants and a GDP trailing Switzerland for #20 on the world country rankings,"

I think this statement needs to be edited. The GDP number is for "Greater Nagoya", which has 12 million inhabitants, not just the 2.25 million in the actual city. See http://greaternagoya.org/en/eco_inf/eco.html.

[VHM: Thanks for catching that. The author copied and pasted wrong. It's fixed now.]

Doc Roc said,

March 26, 2016 @ 6:22 pm

When we lived in Kanagawa Prefecture 神奈川県 in 1983-4, my son was between three and four years old. He loved anpan アンパン, a sweet roll filled with red bean paste, which he called "adzuki bean chocolate."

Joseph said,

March 27, 2016 @ 1:50 am

I can see why the people of Nagoya call it the boonies. When I visited it was striking to me how dark all of the tall buildings were around the main train station, and how there were no tall buildings elsewhere in the city as a walked all the way to the beautiful wall of the Nagoya Castle.

The Japanese don't need DAI語 to write more abbreviated messages since the kanji are the most abbreviated writing system there is. For example, DAI語's GIGS " (郷 に入りては郷に従え gō ni ireba gō ni shitagae) can already be written in four characters as ru xiang sui su 入鄉隨俗. It will be a sad day if the kanji are forgotten and replaced with DAI語.

Joseph said,

March 27, 2016 @ 1:54 am

In my comment above I forgot the would DAI in Japanese could possibly represent the character 代 making a meaning of 代語 or substitute language. It seems like this play on words may have been intended.

flow said,

March 27, 2016 @ 8:05 am

"and a particularly Nagoya favorite, adzuki jam—often an extra \100, roughly the commonsense equivalent of a dollar"—for everyone outside of Japan, that \ (backslash) symbol was probably meant to represent ¥ (Yen sign). Way back before the advent of Unicode, a number of encoding schemes for Japanese had the latter in the position of the former; this was convenient because that way you could use a US keyboard and type both $ and ¥. It was sort of a usability disaster, though, because MS Windows insists on using the backslash in file system paths in lieu of the / (forward slash), meaning that Japanese Windows users have to deal with C:¥ugly¥yensigns on the command line.

I had no idea that the association between backslash and Yen sign is still so ingrained, to this day, that mail from Japan still means you have to mentally swap \ and ¥. Turns out it's a thing, though; read https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Backslash#Confusion_in_Usage for some background, or http://answers.microsoft.com/en-us/office/forum/office_2010-word/change-yen-symbol-to-backslash/5bd48ad1-534e-e011-8dfc-68b599b31bf5?auth=1 to learn how to have MS Word 2010 do the conversion for you (or keep it from doing it for you: "go to File, Options, Advanced, at the bottom click on Layout Options and uncheck 'Convert backslash' characters into yen signs").

Victor Mair said,

March 27, 2016 @ 8:14 am

@Joseph:

Since this post is about Japanese language issues, which you yourself were discussing, why did you switch to Mandarin pronunciation for rùxiāngsuísú 入鄉隨俗 (equivalent to "When in Rome, do as the Romans do")?

Nanani said,

March 27, 2016 @ 2:05 pm

DAIGO could hardly be a flash in the pan seeing as he has been all over Japanese TV (with a musical career and acting and so on) for over a decade now.

Perhaps you meant the popularity of DAI語, but if so it seems strange to use "his" to refer to a language style.

Joseph said,

March 28, 2016 @ 10:03 am

@Victor Mair:

The four character idiom I meant to use, on page 304 or Morohashi volume 11, is 入郷従郷 (meaning also when in Rome, do as the Romans do) because the Japanese kun'yomi or explanation reading is gō ni itte wa gō ni shitagae 郷 に入っては郷に従え which is "GIGS" in DAI語. Note that this kun'yomi reading, or a slightly modified and corrupted form of it, had become the standard modern Japanese word for when in Rome, do as the Romans do. Thus, it seems kind of ironic and interesting in this case that a set of four characters turned into a longer word only to turn back into another set of four characters. I think 入郷従郷 can also be read in Japanese as something like nyu kyou shou kyou, but I'm not sure of pronouncing Japanese like this and I wrote Mandarin pronunciation.

Victor Mair said,

March 28, 2016 @ 6:54 pm

@Joseph

Morohashi is a dictionary of Chinese, not Japanese. So I can understand why you were tempted to provide a Mandarin transcription for the saying rùxiāng cóngxiāng 入郷従郷, but it is perhaps more of a Chinese saying than it is a Japanese saying — especially when you read it that way.

If you use an onyomi reading for 入郷従郷, that would be nyūkyō jyūkyō. But if you read that out to Japanese, the likelihood of their understanding it would not be very high unless they took their time with it and made a special effort to figure it out.

It's possible to classify nyūkyō jyūkyō 入郷従郷 as a yojijukugo 四字熟語 ("four character idiomatic compound"), but it's not a part of common parlance.

The equivalent in Japanese is gō ni itte wa gō ni shitagae 郷に入っては郷に従え. All Japanese who hear that will understand what it means.

Here is an online dictionary entry for gō ni itte wa gō ni shitagae 郷に入っては郷に従え, with parallels in nearly two dozen different languages.

From Ashley Liu:

=====

Many Chinese traditional sayings have Japanese versions. The Japanese don't always keep the original Chinese syntax and like to convert them into Japanese syntax; one has to be really highly educated to know how it's written and correctly pronounced in original Chinese syntax. As you see in the definition, the Japanese usage is broader than Chinese usage.

Here's an example of Japanese common usage of the saying on following the rules of your company.

=====

I asked Japanese colleagues and half a dozen graduate students from the mainland who are fluent in Mandarin and in Japanese their impression of the usage of nyūkyō jyūkyō 入郷従郷 in Japanese. Here are some of their responses:

Fangdan Li:

=====

Since it does mean something in Japanese, the Japanese people should be able to understand it. However, I never used this word with a Japanese or heard a Japanese use it before, I’m not sure if it is commonly used in Japanese.

=====

Tianran Hang:

=====

I have not encountered this particular phrase in Japanese before, but my instinct is that it derives (or shares the same origin) as the Chinese idiom rùxiāngsuísú 入鄉隨俗. If this is the case, then I would guess the saying would probably be pronounced in onyomi 音読み (Chinese style reading): 入(にゅう)郷(ごう・きょう)従(じゅう)郷(ごう・きょう).

And I searched it on Google and a similar saying in Japanese popped out: 郷に入っては郷に従う(ごうにいってはごうにしたがえ) — links here and here.

This is a rather more familiar idiom in Japanese and is said to be derived from the textbook 童子教(どうじきょう ["teaching for children"]) complied by a Tendai monk Annen(安然 あんねん [841-889?]) during the Medieval Period. In this way it is pronounced in kunyomi 訓読み (Japanese style reading). The meaning of the phrase is exactly the same as the Chinese rùxiāngsuísú 入鄉隨俗.

If read directly using the Chinese-derived onyomi 音読み version, it would probably sound unfamiliar to most Japanese ears. They would guess out the meaning, but would probably not use the phrase themselves in this way.

=====

Mengnan Zhang:

=====

I don't think normal Japanese people would understand it if it were read aloud in Japanese since this is not a common word that people would use in everyday life.

=====

[Thanks also to Hiroko Sherry and Cecilia Segawa Seigle]