Combating stereotypes — with stereotypes

« previous post | next post »

Laura Starecheski, "Can Changing How You Sound Help You Find Your Voice?", NPR All Things Considered 10/14/2014:

Just having a feminine voice means you're probably not as capable at your job.

At least, studies suggest, that's what many people in the United States think.

There's a gender bias in how Americans perceive feminine voices: as insecure, less competent and less trustworthy. This can be a problem — especially for women jockeying for power in male-dominated fields, like law.

The first of those studies seems sound to me, but as I noted a few months ago ("Vocal fry probably doesn't harm your career prospects", 6/7/2014), the second study seems mainly to have shown that listeners are put off by people who try to imitate a voice-quality that isn't natural to them. The All Things Considered piece goes on, paradoxically, to try to combat voice-based stereotyping by promoting voice-based stereotyping:

Men often speak in more of monotone, with a percussive, staccato rhythm, explains Annette Masson, a voice coach at the University of Michigan who works with actors, singers and sometimes other professionals, like Hanna. Feminine speech patterns — more musical, with more pitch variation — reflect the different way women connect with other people, she says.

Women tend to be more collaborative communicators than men, Masson says. We say "we" more than we say "I."

"Musicality" is in the ear of the listener, I guess, but "pitch variation" can be quantified. And Eli Anne Eiesland, who wrote to me about this, asked

Do women really have more pitch variation in their speech? That sounds like something that might be true, but also like it could just be made-up stereotypes. Likewise with the claim that women use "we" more than "I". I looked at your post about pronoun use in facebook posts, but I can't say that the difference between first person pronouns looked all that big.

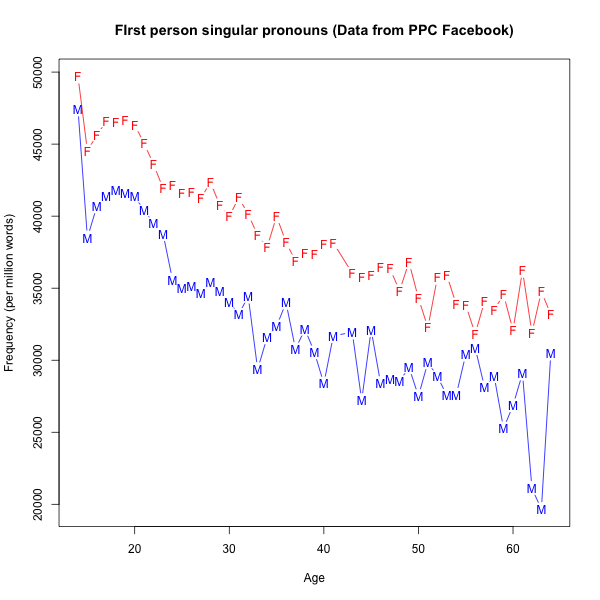

It's certainly not true that women "use 'we' more than 'I'" — in fact they typically use "I" many times more often than "we", in pretty much genre and context, just as men do. In the Facebook data (see "Sex, age, and pronouns on Facebook", 9/19/2014), women actually use first-person singular pronouns (I, me, my, mine) more than men. And in the same dataset, there's essentially no sex difference in the use of first-person plural pronouns (we, us, our, ours):

|

|

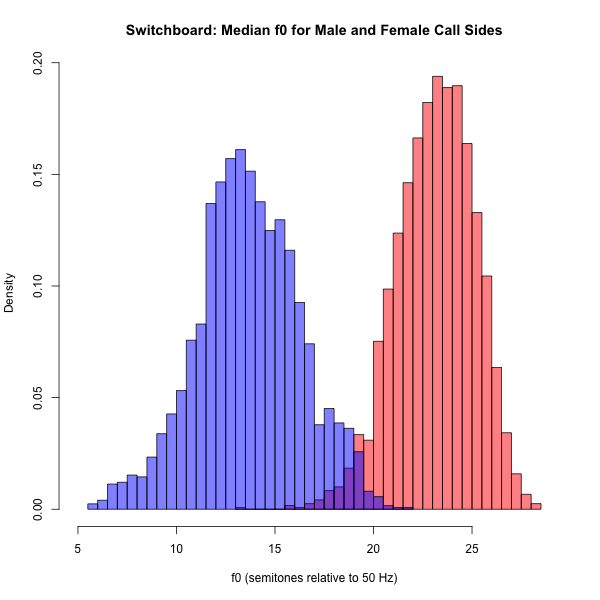

But what about the question of pitch variation? There's no doubt that post-pubescent women have higher voices, in general, than post-pubescent men. Here is the distribution of median f0 (fundamental frequency) values in 2,393 female call sides from the Switchboard corpus, compared to the distribution of f0 values in 2,483 male call sides. The left-hand plot shows the distributions in Hz (cycles per second), while the right-hand plot shows the distributions in semitones relative to 50 Hz.

|

|

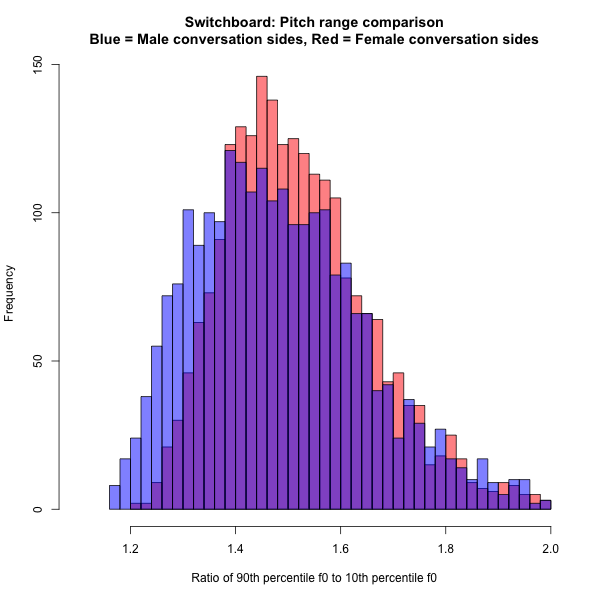

On either scale, there's very little overlap — this is a case where the infamous "gender binary" really is pretty binary, since 99+ percent of humans are chromosomally either XX or XY, and respond in the typical way to testosterone, which causes the larynx to increase substantially in size at puberty for the XY genotype. (For more, see "Biology, sex, culture, and pitch", 8/16/2013.) However, this doesn't tell us anything about "pitch variation", since that's a matter of pitch ratios — and a baritone or tenor can in principle execute the same set of pitch ratios, i.e. musical intervals, as an alto or soprano. One simple way to look at pitch variation is to calculate, for each speaker, the ratio between the 90th percentile of f0 values and the 10th percentile. Here's what the distribution of that ratio looks like for the male and female speakers in Switchboard. As before, the blue histogram is the male speakers, and the red histogram is the female speakers — but now the purple part, where blue and red overlap, dominates the display:  There are a few more male speakers on the low-ratio left-hand side of the graph, and a few more female speakers in the middle-ratio area, but mostly the distributions are quite similar. And I'd bet that the mumblers on the left margin are not impressing anyone as especially secure, competent, or hireable.

There are a few more male speakers on the low-ratio left-hand side of the graph, and a few more female speakers in the middle-ratio area, but mostly the distributions are quite similar. And I'd bet that the mumblers on the left margin are not impressing anyone as especially secure, competent, or hireable.

Larry Sheldon said,

October 18, 2014 @ 1:31 am

Why can I not share links to valuable stuff here to Facebook?

[(myl) Does the Facebook button in the panel at the bottom of the post not work for you?

]

maidhc said,

October 18, 2014 @ 3:33 am

I guess I don't understand what a feminine voice is. Women have a variety of voices. What makes one more or less feminine? Pitch alone? Pitch variation?

Take someone who would I think be considered as an authoritative speaker: Terry Gross. Does she have a feminine voice? I would say she does, according to my own definition. But according to the definition in this study?

Bob Ladd said,

October 18, 2014 @ 5:17 am

For the musically minded but mathematically challenged, it may be useful to translate the pitch range graph as follows: for the "mumblers on the left", 80% of their pitch values fall within a range of about 3 semitones – say, between A and C on the piano – while for the animated speakers way over on the right, the corresponding range is roughly an octave. The peak of the female distribution corresponds to a range of just under a fifth, and the peak of the male distribution to a range of about a tritone or 6 semitones (i.e. the difference between the male peak and the female peak is less than a semitone). None of this changes Mark's point that the distributions substantially overlap, but it may make it easier for some people to get an idea of what "monotone" really means in this context.

Eric P Smith said,

October 18, 2014 @ 5:51 am

Why do you call speakers with little pitch variation "mumblers"? As I understand it, to mumble is to speak indistinctly and without confidence. Where I come from (Scotland, central belt) many speakers have little pitch variation but are thoroughly clear and confident. Instance Judy Murray, the mother of Andy Murray the tennis player, who is way to the left on your pitch range graph. Listeners not used to the Scottish voice may have difficulty with her accent, but no-one could accuse her of mumbling.

[(myl) Two reasons. First, there's a strong correlation, within any given speaker's productions, between vocal effort and pitch range. So in a fixed context — telephone conversations with strangers — the examples on the low end of the pitch-range distribution are likely to be on the low end of the vocal-effort distribution as well. And second, the stereotype threaded through the NPR piece is that a monotone pitch range is manly, confident, and competent — but in fact it can also be found in someone who is shy, withdrawn, and verbally unimpressive.

In the interview that you link to, Judy Murray's 90/10 ratio is about 213/168, or 1.27. (About 4.14 semitones, as Bob Ladd would tell you.) This is certainly on the left-hand side of the distribution given above, and I agree with you that she's not mumbling. In fact she's having to speak fairly loudly, over a considerable amount of background noise.

Whether for that or some other reason, Ms. Murray's 90/10 ratio in this TV appearance is somewhat larger, namely 250/178, or about 1.40 (5.9 semitones).]

Dominik Lukes (@techczech) said,

October 18, 2014 @ 6:59 am

I think you underestimate how tiny differences in the distribution of features in a population can accumulate impact on both stereotypes and material consequences of these stereotypes. I recommend Virginia Valian's book 'Why so slow' that has some nice models how differences imperceptible in daily life may add up to systemic inequalities.

[(myl) But it's also true, through the miracle of confirmation bias, that stereotypes can arise and be maintained when the difference is non-existent or actually in the opposite direction.]

Also, there's the amplifying effect of stereotype bias that needs to be taken into account. Again, the differences can be quite minute but they do add up.

On the other hand, it is important to put the truth about the real distributions out there and combat the stereotype. But it does not necessarily mean that even the tiny difference that is conversationally magnified by the stereotype into a binary distinction wasn't actually a factor in the systemic outcomes.

Eric P Smith said,

October 18, 2014 @ 3:01 pm

@myl: Thanks for your thorough reply.

D.O. said,

October 18, 2014 @ 6:31 pm

I am almost sure that there is no sizable effect anyways, but monotone (or little pitch variation) does not mean a speaker's pitch varies only slightly throughout. It implies more local variation. Maybe we could look at correlation coefficient between successive syllables?

[(myl) This is a good point, but looking at measures of local variation requires somewhat more sophisticated processing. I'll see if I can come up with a reliable cheap proxy measure.]

D.O. said,

October 18, 2014 @ 6:37 pm

Also, whatever is actually true for pitch variation, it is possible that what is perceived as "monotone" is more of a constant loudness rather than frequency, despite the name. The two variations must be correlated though…

Eli Anne said,

October 20, 2014 @ 4:39 am

Hey, thanks for writing about this, awesome :-D