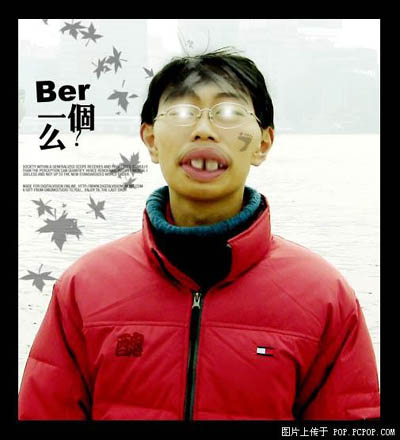

Kiss kiss / BER: Chinese photoshop victim

« previous post | next post »

David Moser sent this photo to me about five years ago and I'm only now getting around to unearthing it from the masses of files scattered over my desktop:

As David exclaimed when I told him that I had found his old message, "Ha! Great! At any rate, nothing has changed in five years, it's still a timely problem."

In Pekingese colloquial, the word BER is often used to describe a quick, light kiss, a "peck" as we would say in English, hence the irony of this photo. It is not an uncommon term in Pekingese; if you listen in on the conversations of real BeijingeRs (PekingeRs, if I may), chances are that you'll hear it surface in their rapid fire patois from time to time.

The problem is that we have this morpheme in spoken Pekingese, but nobody is really sure how to write it in characters. The same is true of many other morphemes in the spoken language, although frequently frustrated character enthusiasts will retroactively assign this or that combination of characters to write an expression from the spoken language and then ex post facto justify their reading (e.g., the contortions they go through to explain the different ways ["bury the bill; buy the bill", etc.] they write Cantonese MAIDAN ["bring the bill"]).

David remarks:

The short Chinese question, which reads "Ber yīge me? / Ber一個么?", roughly meaning "Do you wanna give me a kiss?" is intended to be funny. "Ber yīge ba / Ber一个吧 is a common cutesy phrase, usually used with kids, that means "Give me a kiss". (Hard to reproduce the tone of it, but something like "Gimme a kissy-kissy" or the like.)

First of all, we may assume that the me 么 is meant to substitute for ma 吗 (interrogative particle), but the main thing is the pinyin. I've heard this phrase often myself, and never knew the character for it, and apparently most Chinese aren't sure, either. I just tried searching on the Internet, and found numerous instances on blogs and other websites where others had resorted to this, a lot of hits for "ber一个", indicating that a huge number of people don't know which character this is. I've never been sure, either, whether it's "bei + r" or "ben +r" or "beng + r" or what. I asked my wife and a few other people, and most either don't know or seem to think the proper character is bo1 波, though one guessed 啵 with a mouth radical, and I did find many hits for "啵儿一个", which would maybe be pronounced "ber" as well, I guess. This surprised me. I haven't been able to find a dictionary that gives the definition of "kiss" for any of these characters, which makes me think there perhaps isn't a standard graph for this item. I don't know if you've written about this one yet, but "ber yige ba" (or "bor yige ba", however you would write it) is really very, very common in Beijing at least, and I don't know to what extent in other parts of China.

Whoever did this photoshop was no doubt completely clueless as to how to write it, and had to resort to an alien writing system to write their native language. It's just our old friend the "morpheme with no graph". I'm sure the morpheme probably does have a graph, just that virtually no one knows it. I'm not sure if the retroflex syllable is "ben" or "beng" or maybe even "bo", which I think someone once told me it was. I could find no one who knew the appropriate graph.

By the way, "benr yi ge" is usually used by parents talking to children, or adults being silly with each other, and just means something like "give me a kissy-poo', "kissy-kiss".

If we do a Google search now (the middle of 2014; David wrote the above in 2009) on 啵儿一个 or 波儿一个, we do get a lot of hits, but many of them are false hits because they are broken up by punctuation and refer to something else than the expression under discussion in this post.

Two days ago I did a search on "ber一个" and got 19,100 hits.

For the record, bō 波 means "wave" and bo 啵 is a particle whose usage is similar to that of ba “吧” for denoting a request, command, etc., mainly used in early vernacular. So neither of these characters can be the true běnzì 本字 ("original graph") for the "ber" of "ber一个".

I seldom (almost never) disagree with David on anything, but I would not be so sure that there is a character for writing this morpheme (anyway, David qualified his "sure" with "probably").

I've even seen this "ber一个" written as "吅儿一个" where the two mouths are graphically meant to depict a kiss. But this is not the true character for writing the "ber" of "ber一个" either, since 吅 is actually pronounced as xuān (said to be equal to 喧) and mean "clamor; call out loudly" or sòng (said to be equal to 讼) and mean ("dispute; argue; debate; litigate; bring a case to court"). Consequently, the two characters that are most often pressed into service to write the "ber" of "ber一个" are definitely not the true běnzì 本字 ("original graph") for the "ber" of "ber一个".

As if that were not dismaying enough for hanzi enthusiasts, the situation is further complicated by phonological constraints. Knowledgeable informants on Pekingese pronunciation have told me that the "ber" of "ber一个" is actually closer to "benr" or "beir" than just "ber".

Nonetheless, we also find the character with the mouth radical used in related expressions such as dǎbobo 打啵啵 and dǎbor 打啵儿, both of which mean "to kiss" (dǎ 打 is the multipurpose verb meaning "strike; beat; hit; do" — there are at least two dozen more meanings for this verb).

"Ber yīge / Ber一個" ("kissy-poo; kiss-kiss") now has a competitor, "mua yīge / mua一個" ("smooch; smack"), something I was completely unaware of five years ago. A web search for "mua一個" will get you a mind-boggling 244,000 ghits.

Now, if the character for the "ber" of "ber一个" is uncertain, the "mua" of "mua一個" is even less writable in sinographs, since it's not even a permissible syllable in Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM). This is further evidence that the Roman alphabet has become a part of the Chinese writing system. See here, here, here, here, here (no. 45), and here.

It would be interesting to see how Wang Shuo or other writers of highly colloquial Pekingese fiction write these expressions. I would imagine that, if they are being true to the speech of real Pekingers, they would often be faced with the dilemma of how to write popular expressions in characters (Lao She, the famous Peking novelist of a previous generation, often confronted this challenge). Ditto for authors who wish to write colloquial expressions from other topolects.

Sinitic Morphemes in Search of Characters

The difficulty of writing genuinely colloquial Pekingese in Chinese characters is a subject that we have often addressed on Language Log. Here is a sampling of some of the relevant posts:

- Sayable but not writable

- Surprising Transformations of a Beijing Street Name

- Pushing Pekingese

- OMG moments induced by allegro forms in Pekingese

- Pekingese put-downs

- Real BeijingeRs

- Trainspotting-like Voices in Chinese

When it comes to other, non-Mandarin topolects (Cantonese, Taiwanese, Shanghainese, etc.), the difficulty of writing all the morphemes of their colloquial forms is even greater, but I shall refrain from listing the relevant posts here, since they are too numerous even to begin to enumerate.

[Thanks to Brendan O'Kane, Rebecca Fu, Gianni Wan, Zhao Lu, Jing Wen, Jiajia Wang, and Ziwei He]

Brendan said,

July 22, 2014 @ 4:16 pm

For what it's worth, my wife (who grew up in the PLA compound used for filming the movie In the Heat of the Sun/阳光灿烂的日子, based on Wang Shuo's novella The Animal Years/动物凶猛) said when I asked her about this that the character was 啵, and that she had "learned it from Taiwanese TV." (Perhaps the subtitles on 康熙來了 or some similar variety show.) This is common enough, but it seems strange: "bor" is definitely distinct from "ber" (which I'd always heard as being either "beir," like the common Beijinghua 倍儿 but with a different tone, or "benr"); just ask a Beijinghua speaker to say a common phrase like "又来了一波人" to confirm this. Chen Gang's dictionary of Beijinghua terms doesn't seem to have anything plausible for "ber," unfortunately; neither does the more recent 北京话词典 edited by Gao Wenjun and Fu Min.

Rubrick said,

July 22, 2014 @ 4:27 pm

I'm not entirely clear on what it would mean for a (modern) word to "have" a graph which virtually no one knows. Is there a central authority which lists all "official" graphs? If not, there doesn't seem to be much meaning to having a graph outside of what people choose to use for a given word; and if so, surely one can just look up BER to see if it has one?

david said,

July 22, 2014 @ 4:36 pm

mwa is text-messaging for a kiss. Saying an unvoiced mwa produces the lip movements often used to send a kiss to some one watching at a distance. The Urban Dictionary in 2008 said it was mainly used by Arabic people.

Terry Collmann said,

July 22, 2014 @ 6:16 pm

David – "mwa is text-messaging for a kiss."

"Mwa" is what pretentious people actually say when air-kissing someone. See here at 1:55

David Moser said,

July 22, 2014 @ 9:22 pm

Dear Rubrick,

For those who don't know the basics of the Chinese script, your question would seem to be a reasonable one. If you do a little investigation on the problematic relationship between Chinese characters and the sounds of Chinese, you'll see that the problem is quite complex. I would suggest you first read the list of articles Prof. Mair has linked to under "Sinitic Morphemes in Search of Characters." You'll quickly see the problem.

David Moser said,

July 22, 2014 @ 9:31 pm

By the way, the opposite problem — graphs for which people are unsure of the pronunciation — is also common in Chinese, for the same reasons.

Which reminds me of when Prince changed his name to a strange hieroglyphic-like symbol, causing the media to coin the phrase "the artist formerly known as 'Prince'" to refer to him.

I'm also reminded of the whimsical Superman villain Mr. Mxyzptlk, a favorite of fans for years, who could never quite agree on how to pronounce the name. See:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mister_Mxyzptlk

David Moser said,

July 22, 2014 @ 9:34 pm

Sorry for the barrage of posts, but just for good measure, you can check out this article "Some Things Chinese Characters Can’t Do-Be-Do-Be-Do", at Pinyin.info:

http://pinyin.info/readings/moser/chinese_characters.html

Rubrick said,

July 22, 2014 @ 11:36 pm

@David Moser:

I follow Prof. Mair's posts closely (or as closely as someone who doesn't speak any Sinitic languages can hope to do), and understand the complexity of the relationship between speech and characters. What's confusing me is the concept of "běnzì". If this term originated in speech, rather than writing (which seems likely), why would there be any expectation at all that it would have such an "original graph"? Who would be the originator?

Is the idea that there is a supposition (clearly false in practice) that Chinese speakers can only coin new words which are based on existing characters?

Stephan Stiller said,

July 23, 2014 @ 7:12 am

Surely the actual problem is this: While any alphabetic writing system lets people write whatever they wish, writing systems with lower degrees of phoneticity waste the time of both writer and reader, because they will need to spend time thinking about how to encode and decode between speech and symbols for anything without an established orthography.

David Moser said,

July 23, 2014 @ 10:28 am

@Rubrick

Stephan Stiller is on the right track. The point of this example in Prof. Mair's post is not so much the question of determining what the appropriate or "correct" graph should be. Rather, the point is this deficiency in the writing system that Stephan Stiller mentions. The point is that the person creating this photoshop joke simply "gave up" on the writing system altogether and resorted to the latin alphabet and pinyin. And the larger issue is that native speakers often resort to wild guesses, or pinyin, or even English to write words that already have a well established, standard character. Chinese script is just terribly non-user friendly in this regard. English orthography allows me to make up a word like "splorg" and write it phonetically. I'm certainly free to make up a nonsense word in Chinese as well, but how am I supposed to write it? As Stephan says, I have to put some thought into the problem, and the usual solution is to give up.

JS said,

July 23, 2014 @ 2:04 pm

As regards Chinese, it seems to me that the implicit assumption is often that there is no such thing as ex nihilo coinage; that all words have a history and thus ought to have been written down in some way or ways in the past which, by dint of their vintage, are to be seen as more proper than whatever seat-of-the-pants solution we might come up with today. To some, this properness is not merely a matter of vintage — hardcore běnzìists seem to feel it ought to be possible to associate every (monosyllabic) word with a single character first tailored specifically to write it. The truth about a script like the Chinese is of course that, given the desire to write new words or words for which one is unaware of a written form, you just have to make something up — with different people making up different somethings, often by borrowing extant characters or components based on their phonetic (or semantic) value vis-a-vis other words… a process which has been going on from the very, very beginning.

I'm also fascinated by David Moser's article, linked above, but think the inflexibility he points to (basically, "why is it impossible to write a Chinese splorg?") is a function of the language and not of the script (though that the script is as it is may in part be a function of certain properties of the language). It might seem we have, with the alphabet, the capacity for limitless intercombination of individual sounds to create "nonsense" words like splorg, but such creations are strictly governed by English phonotactics: spl and rg are regular initial and final consonant clusters respectively (we can't exchange the two, nor could we arrange the individual constituents of either in any other order.) (Note this approximate phoneme string would even occur during the utterance of a phrase like "explore Greenland.") By contrast, the hypothetical Mandarin nonce creations suggested in the article (ging, etc.) violate ironclad phonotactic constraints — no monolingual speaker of Mandarin Chinese, Ella Fitzgerald clone or not, would generate such a syllable, whatever the nature of her script.

Maybe the problem gets a bit trickier than this: native speakers of all languages have subconscious and robust knowledge of the legality of particular sound combinations, but in Chinese languages, as distinct from English, one important class of such restrictions involves the ways certain (classes of) consonants may or may not combine with particular (classes of) vowels ("co-restrictions") — thus precluded are David Moser's hypothetical Mandarin ging and shuing (only the so-called "palatal" consonants precede /i/) as well as puan and dua (the prevocalic glide /w/ occurs only in very particular contexts.) But the whole engine is driven by frequency relations and is not absolute — things like bou, shong, etc., for example, would rate higher than the above in wordlikeness (that is, they're "accidental gaps"), meaning a creative Chinese scat singer would be more likely to generate them. Ultimately, I think even the fact that a Mandarin speaker, while sure to much prefer bou to ging, will probably reject it more forcefully than an English speaker would reject something analogous like splorg, is explicable via statistical description of co-occurrence patterns and has nothing to do with the script.

Randy Alexander said,

July 23, 2014 @ 3:43 pm

DM:"Whoever did this photoshop was no doubt completely clueless as to how to write it, and had to resort to an alien writing system to write their native language."

Clueless? Alien writing system? The Roman alphabet is certainly not alien to Chinese people. I really doubt the person who made this scratched their head for any length of time and then finally broke down and woefully had to resort to using an alien script

Randy Alexander said,

July 23, 2014 @ 3:44 pm

to write that. (And then felt dirty afterward.)

Victor Mair said,

July 23, 2014 @ 3:48 pm

From a historical phonologist who is also a specialist on the evolution of the Chinese script:

Does anyone really argue that the Chinese script is a whole writing system for modern language?

Victor Mair said,

July 23, 2014 @ 3:50 pm

From a native speaker of Mandarin and several other topolects:

Romanization is much better for transcribing sounds in Chinese than characters.

Richard Warmington said,

July 23, 2014 @ 4:28 pm

There is this entry in Chao & Yang's "Concise Dictionary of Spoken Chinese" (1947):

邋, 落 lah. 邋了 to leave behind (through forgetfulness); to omit unintentionally.

["lah" is the GR equivalent of pinyin "la4"]

I can find no other dictionary that lists 邋 with this pronunciation and meaning, nor can I find an example of its usage in that sense on the Web.

A contact suggests that la4 was probably "one of those spoken dialectal words that were never written" and that "Chao (and maybe others) thought it was a good idea to write it 邋. Others probably *imagined* that it was related to 落, and obviously they won the day. lao for luo is a common thing, and there are all kinds of words for which this evolution is seen (uo->ao). la is much more improbable, and Chao had his reasons I guess. But maybe not based on actual usage. For Chao, la4 was a common word (in Beijing usage), so he had to include it; but maybe nobody had ever used it in writing."

Eidolon said,

July 23, 2014 @ 6:17 pm

I think it's worth observing that for transcribing sounds, the Chinese writing system is a syllabary, while alphabetic writing systems are phonemic. Alphabets operate at a lower level of abstraction than syllabaries and are therefore capable of expressing a greater range of variation. There are still limitations, of course – for example, the standard Roman alphabet isn't capable of distinguishing between Chinese tones, and is therefore insufficient for transcribing the Sinitic languages. Pinyin, however, is fully capable of doing so because of its extended phonemic range. Nonetheless, there are sounds pinyin isn't capable of expressing, too.

But given that the range of phonemes humans are capable of expressing is ultimately finite, one has to believe that there exists a hypothetical universal alphabet that is capable of transcribing all languages, both extant and hypothetical…

David Moser said,

July 23, 2014 @ 10:41 pm

@JS

Very good, your comments about the primacy of the phonotactic constraints of the sound system of Chinese over the writing system are well taken, and I agree with you. And of course, as you say, those constraints operate in English orthography as well. "Splorg" rolls off the tongue, but "slporg" doesn't. Eidolon's point about the characters as syllabic morphemes is good to keep in mind, too, and is something I mention in the article as well. The "grain" of the writing system is coarser than that of an alphabetic language, and this can influence or limit the speakers's degree of conscious phonetic awareness.

Victor Mair said,

July 24, 2014 @ 5:50 am

Phonotactics vs. the Script

Does the Chinese script make it difficult to record certain morphemes in the spoken language?

I still think that David Moser is correct for at least two reasons:

a. there are no BEN3ZI4 (supposed "original characters") for new morphemes that arise spontaneously or are borrowed

b. it is impossible with characters to write certain sounds, such as MUA, that are actually being spoken every day

It is precisely for reasons such as these that people are increasingly turning to the alphabet to write these expressions.

MUA is not the only example. Conspicuous and ubiquitous is QQ, which is pronounced the way it looks. When Lu Xun, the greatest Chinese writer of the 20th century, wrote "The True Story of Ah Q" in 1921-22, he made a big show of trying to figure out how the "Q" of the (anti-)hero's name was pronounced and what hanzi / kanji it stood for. No longer do Chinese think that "Q" might be pronounced qiu or gui. Now it is simply Q (sounding like "queue").

The alphabet permits us to write, and pronounce, such things as "tsetse fly", "Mozart", "intaglio", "neoguri" (even though the Revised Romanization for Korean is not optimal for English speakers), Ürumchi (cf. Mandarin Wūlǔmùqí 乌鲁木齐, which is far from the Uyghur), etc. that were not originally part of English phonotactics, but were acquired through borrowing or phonological change within English. I could easily give examples of dozens of other borrowings with phonemes that have been brought along with the alphabetically represented words of which they are a part.

During the past few years on Language Log, I have given plenty of evidence (partially documented in the links and bibliography of the original post (above) of Chinese speakers adopting "lettered words" into their vocabulary. Not only has the Roman alphabet been assimilated into the Chinese writing system (check the back of the Xiandai Hanyu cidian), Chinese speakers are increasingly *directly* using expressions that cannot be written in characters, and they are no longer forcing such expessions into a Mandarin phonological framework consisting only of morphosyllabic characters.

Note: the phonotactics of Shanghainese, Cantonese, Taiwanese, etc. are quite different from those of Modern Standard Mandarin. That is why "captain", when borrowed into Shanghainese, sounded all right, but when transferred via characters from Shanghainese into Mandarin sounded odd (Jiǎbìdān 甲必丹), ditto for taxi in Cantonese when transferred via characters into Mandarin (díshì 的士).

I have noticed during the past decade that my Chinese students and friends are increasingly using borrowed terms in their speech and are pronouncing them as they are spelled with the alphabet, not as they are transcribed in characters. Looking at their text messages and e-mails, which are peppered with Roman letter words, it is clear that they are not bothering to transfer terms from abroad into Chinese character forms, but are writing them and pronouncing them independently of the morphosyllabic character system.

Stephan Stiller said,

July 25, 2014 @ 4:35 am

I will add one point, complementing what has been written so far in this thread.

It is true that the decoding of text into speech is limited by English phonotactics too in certain ways. It is also the case that there are plenty of design annoyances of English orthography that don't even let one express all that's phonotactically possible in an unambiguous way. An example is given by the many language guides which try to indicate pronunciations in a self-made respelling system. They invariably run into the problem of how to distinguish between /aʊ/ and /oʊ/: the most obvious letter sequences – "ou" and "ow" – are inherently ambiguous, and the rest doesn't give stable results across all contexts either.

But that accidental but phonotactically unobjectionable gaps such as pinyin "lǖ" can't be represented is inherent to the design (if one can call it that) of the Chinese writing system. Such annoyances are less frequent in alphabetic writing systems.

@Eidolon

While microvariation in the phonetic realization of phonemes (according to many dimensions: place of articulation for consonants, vowel height, vowel duration, …) is inherently hard to capture, a very impressive project is Luciano Canepari's canIPA.

quill said,

July 25, 2014 @ 11:32 am

bei is the verb of choice for cantonese and a few other sintic languages for the verb to give.

JS said,

July 25, 2014 @ 5:39 pm

As regards the potential to convey to speakers of Language X entirely novel (i.e., foreign) phonemes, a phonemic writing system (where letters are associated in some more-or-less consistent way with the phonemes of Language X) is naturally insufficient to the task — most speakers of English don't seem to use (word initial) /ts/ in tsetse, still less /ʎ/ in intaglio or /ʌ̜/ in neoguri. Still, it's true that there is a relatively cosmopolitan minority who pronounce such words more faithfully with respect to their original forms, and for whom particular spellings provide meaningful cues: given such an entryway, it's surely true that a more analytic writing system allows for more ready adoption of new sounds or sound combinations by a speech community (witness the role of novel hiragana within Japanese.)

My point would only be, to take one example, that Wūlǔmùqí remains a perfectly normal, legitimate Mandarin re-rendering of Uyghur (from Mongolian?) Ürümchi ئۈرۈمچی — that is, someone entirely illiterate could well have created it. That the English pronunciation /uːˈruːmtʃi/ (via Wikipedia) happens in some respects to be closer to the original is just a function of the phoneme inventories and phonotactics of the three languages involved, and itself has nothing to do with script. Now, if English speakers beyond a coterie of specialists begin to produce "ü" as IPA /y/, we'll have witnessed a special capacity of the alphabet.*

[*Although it's true that this could probably only happen after the place name began to be more widely spelled with "ü" as opposed to "u", with the former not a part of the English alphabet as such.]

Victor Mair said,

July 26, 2014 @ 6:42 am

Linguistic change as recorded by different types of writing systems

The sound system of any given language is not eternally unchanging, elsewise we would never have different stages in the phonological development of languages. Sometimes the changes are subtle, sometimes they are radical.

Taking just a few examples with regard to Mandarin, we have:

1. the palatalization of the velars

2. the loss of entering tone (final -p, -t, -k)

3. the acquisition of retroflexion

In some cases changes are induced from without, in other cases they occur spontaneously from within. Scholars like Mantaro Hashimoto, Charles N. Li, and David Prager Branner point to Altaicization and other similar processes as examples of the former, while William Labov and William S-Y. Wang refer to lexical diffusion as instances of the latter. In my Language Log posts and elsewhere, I have often noted the importance of borrowing, allegro forms, and other linguistic processes as stimuli for nonce or long-term changes in a language. No matter how or why all of these changes take place, once they occur, it is far more easy and more accurate to write them down with an alphabet than with a morphosyllabic script such as hanzi / kanji / hanja.

Ivo Spira said,

July 26, 2014 @ 1:12 pm

On ber/bor:

In Dungan there is бый (in píngshēng), according to Hǎi Fēng 海峰 (2003): 呗 pei²⁴ 亲吻:~一口 [p. 318]

I have no idea whether this form is somehow related to Pekinese bor/ber, but it would be interesting to try to find out.

julie lee said,

July 26, 2014 @ 3:24 pm

@eidolon says:

"Alphabets operate at a lower level of abstraction than syllabaries …"

Could you explain that? I always thought the alphabet operated at a higher level of abstraction than the syllabary. Let's take a syllable BAN 班 in Chinese. I thought it's been said that the Chinese were not able to go to a higher level of abstraction, namely, abstract the sounds b, a, n, from a syllable such as 班 , and that being stuck in a syllabary-based script, and not moving on to an alphabet, has hampered the Chinese ability for abstract thought.

Victor Mair said,

July 26, 2014 @ 5:36 pm

@Ivo Spira

I do not know 呗 as meaning "kiss", only the following meanings:

bei 呗 final particle of assertion

bài 呗 chant

fànbài 梵呗 Buddhist / Sanskrit hymnody

JS said,

July 26, 2014 @ 5:46 pm

The ability to reflect language-internal sound changes directly is clearly a special capability of phonemic or phonemic-ish alphabets, if the users/adjudicators of such systems can be bothered with updates — we're a bit slow on the uptake in the case of English.

julie lee said,

July 26, 2014 @ 8:02 pm

eidolon:

I think I see what you mean now. In computer programming, the language of 0's and 1's is the lowest-level language, and ordinary English is the highest-level language, even though the programming language using only 0's and 1's is in a certain sense the most abstract language. I'm prepared to be corrected.

Victor Mair said,

July 27, 2014 @ 6:38 am

@JS

"we're a bit slow on the uptake in the case of English."

But still a heck of a lot faster than Chinese, whereas Finnish, now….

William Locke said,

July 28, 2014 @ 1:35 am

In regards to all the false 本字 of ber, and following JS's first comment: aren't such "false borrowings" (假借) long-established in Chinese? I remember Wieger, following the 说文解字, lists this as one of the six categories of characters, and gives the example of 萬 being a character that originally meant "scorpion" (pronounced wan) but was borrowed for a word meaning "ten thousand, a myriad" (also pronounced wan) purely on the basis of their similar sound. Would "波儿一个" and other variants not be examples of this same process? (even though, as David Moser points out, the pronunciation of that character and the sound "ber" don't seem ideally matched)

Victor Mair said,

July 28, 2014 @ 6:45 pm

False borrowings and Trail Bologna

Once more on the flexibility of alphabets and the rigidity of the Chinese writing system.

@William Locke

Very well put! You may be the first person ever to connect the "false borrowings" (假借) of Xu Shen's "Six Categories" (liùshū 六書) with false BEN3ZI4 本字. And I'm very happy that people are finally starting to see that many (probably most) so-called 本字 (BEN3ZI4 [supposed "original characters"]) are not really "original" after all, but were false from the very get-go.

As for alphabets being sufficiently flexible as to borrow foreign phonemes, I have an even better example than "intaglio" (which I gave above), namely "Bologna / bologna".

I have always been a stickler for correct spelling and precise pronunciation, even as a little boy in rural Ohio. So when my dad bought famous "Trail Bologna" (that's what was on the package and that's what my dad would write on his grocery lists) but referred to it in speech as "Trail baloney", I was deeply puzzled (and even troubled) by this sound switcheroo. As for the city, whence the sliced meat product got its name, I already knew as a child how it was pronounced, and so did my father and everyone else around me. Listen to the recordings here:

http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Bologna

I have never heard anyone say "buh-log-na", neither for the city nor for the sliced meat.

http://public.wsu.edu/~brians/errors/bologna.html

And tonight, by sheer chance, for dinner I had gnocchi with cheese.

http://www.thefreedictionary.com/gnocchi

William Locke said,

July 28, 2014 @ 10:43 pm

@Victor Mair

Thank you for your reply! Glad to know I wasn't too far off-base.

Looking at "bologna" and "baloney," I have to ask: wouldn't the latter be a better example of alphabetical flexibility? Connecting the spelling of "bologna" to the sound "buh-LOAN-ee" is, as you noted, a confusing process! It almost seems comparable to connecting the characters 波儿, which we might expect to be pronounced "bor," with the pronunciation "ber" (minus the additional semantic confusion of 波 meaning “wave"). The spelling of "baloney," on the other hand, much more closely approximates (in our particular mode of alphabetic writing) how we actually say the sliced meat.

As for the city name, Bologna, I had to click on the link to make sure my own assumed pronunciation was correct. Growing up in the Midwest (United States), I'm aware that pronunciations of place names can drift from their origins. My grandfather's favorite was always "Beaucoup Creek, IL," which Wikipedia says is pronounced "Ba Cou" locally but my grandfather swore was "Buck Up Creek" (this could have been another local variant, or my grandfather's unique sense of humor).

Victor Mair said,

July 29, 2014 @ 2:43 pm

From South Coblin:

假借 doesn’t mean “false borrowing”. 假 itself can mean “to borrow”, so this is really a synonym binome.

JS said,

July 29, 2014 @ 3:57 pm

Jia3 假 (v.) is often better treated as 'coopt, put on, assume': we still have 狐假虎威,假公济私,etc. Jia3 'false' is etymologically speaking a straightforward extension of this word, with the sense of artifice/artificiality arguably original and thus present in jiajie 假借 and the like. We can also compare J. kana 仮名~假名, which is the same idea even if ka 假 is not SJ, as some sources suggest.