A New Morpheme in Mandarin

« previous post | next post »

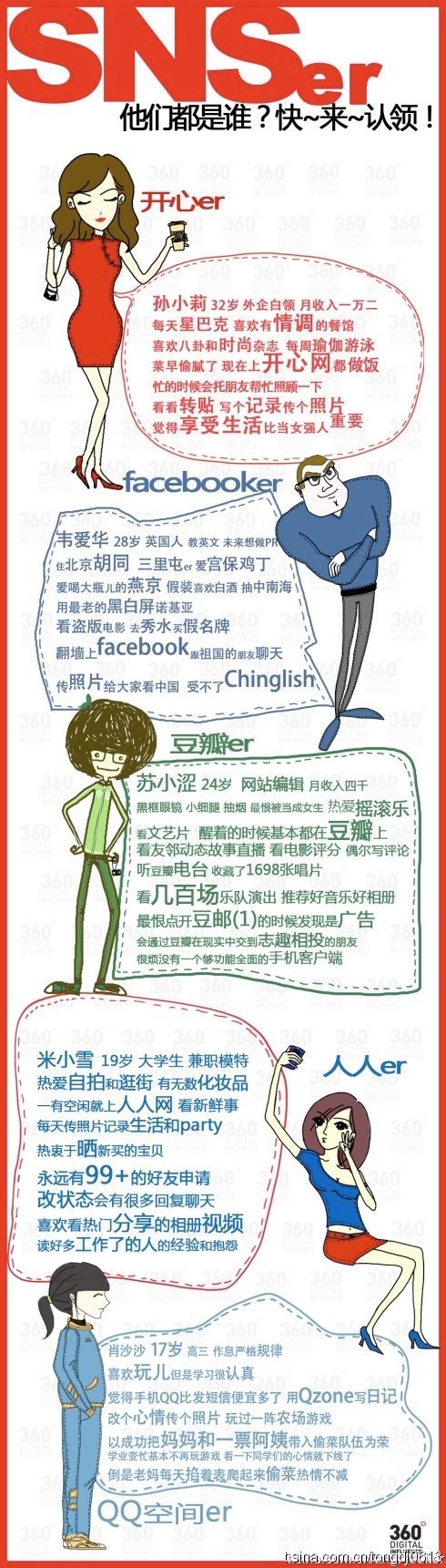

A week ago, Anne Henochowicz sent me the following illustrated introduction to devotees of the five most popular Social Networking Services in China — Facebook (which is off limits to Chinese, but expats and others who can figure out how to get around the Great Firewall are naturally fond of it) and the top four indigenous knock-offs:

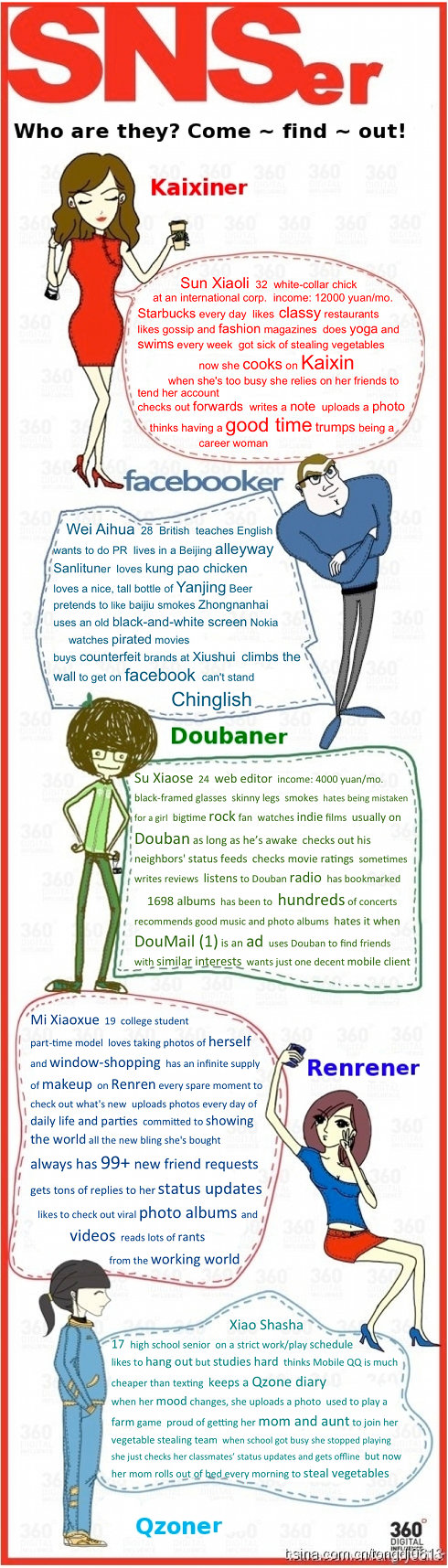

A week later, Anne went the extra mile and delivered this beautifully crafted English translation of the entire text:

An alternative translation may be found here (with brief descriptions of each of the five SNSs, together with a quick summary).

One thing that immediately strikes the reader is the prominent occurrence of Roman letters in the original Chinese text. Since, as Mark Hansell and others have shown, the Roman alphabet has already been incorporated within the Chinese writing system, the frequent appearance of Roman letters in Chinese texts is not all that surprising. But the alphabetical elements in this text go beyond mere acronyms and the occasional inserted English word.

What is remarkable about the Roman letter components of this text is the recurring -er ending in all six titles, from the main title through the five sectional titles — whether English (Facebook) or Chinese (the remaining four). Note, however, that the English plural suffix -s has not been added to SNSer in the main title, although one would expect it to be there if the -er of SNSer were functioning as a purely English suffix .

A few additional notes on the names of the various Chinese SNSs:

Kāixīn

开心

happy

Dòubàn (name of a hutong [alley] in Beijing)

豆瓣

bean segment (used to make a very flavorful type of bean paste [dòubàn jiàng 豆瓣酱])

Rénrén

人人

everybody

QQkōngjiān

QQ空间

QQ space / room / zone

One could write a small treatise about the various meanings and origins of "QQ" in Chinese, but I shall restrict myself here to these observations:

1. in the present instance it derives from ICQ (meaning "I Seek You"), the name of a instant messaging program). At first, the offshoot called itself OICQ ("Open I Seek You"), but when it was sued by ICQ, it changed its name to QQ, which stuck. One of the reasons for this is that "Q" or "QQ" in Chinese often stands for the English word "cute." It helped that fans of QQ were enamored of the company's penguin mascot, which they though was very QQ ("cute").

2. Q or QQ in Taiwanese means "chewy" (like gummy bears and certain kinds of pasta). In any event, all the nice associations of QQ ("chewy") are also in the background when one talks about the QQ instant messaging service. There is no Chinese character for this morpheme in Taiwanese. Although the made-up character [食+丘] is sometimes pressed into service (e.g., khiū-teh-teh [食+丘] 嗲嗲), the Roman letter form of the morpheme (Q or QQ or even QQQ) is far more prevalent (almost always, since [食+丘] is not really an established character).

3. QQ — wouldn't you know it? — is also the name of a car made by Chery Automobile.

4. Another very different meaning for QQ is that of an emoticon showing a person with tears in their eyes.

5. Also said to be related to #4, but not relevant to the IMS in question, is the usage in the popular internet game called Warcraft, where (I am told; I don't know this firsthand) you press ALT+QQ when you are forced to quit. Ex.: "Why don't you QQ, noob?"

About 15 years ago, I wrote a science fiction novel called "China Babel" (still unpublished) in which I described a time in the future when Chinese would merge with English. When I see things like this text about SNSer[s], I begin to think that my futuristic imaginings may not have been that wide of the mark.

[Thanks are due to Jing Wen, Sophie Wei, Melvin Lee, and Grace Wu]

Jim said,

April 26, 2011 @ 6:22 pm

I suspect the "Alt-QQ" etymology is mistaken, but "QQ" is used pretty commonly in WoW culture to describe complaining, especially when it's particularly melodramatic or about something trivial or clichéd.

cntrational said,

April 26, 2011 @ 6:31 pm

Q_Q also looks vaguely like a crying face.

cntrational said,

April 26, 2011 @ 6:33 pm

Oops, you already mentioned that. Excuse me.

The Ridger said,

April 26, 2011 @ 6:42 pm

Is the Facebook guy's personality as obnoxious in China as it would be here? Is this a putdown of Facebook?

John Lawler said,

April 26, 2011 @ 6:54 pm

Jeez, Victor. I just gave a lecture at a Science Fiction convention about linguistics in science fiction. As you know, the list of good science fiction with good linguistic science is short. I sure wish I'd known to add your name to the list.

rootlesscosmo said,

April 26, 2011 @ 7:10 pm

What's the vegetable-stealing about?

Simon said,

April 26, 2011 @ 7:33 pm

http://www.marbridgeconsulting.com/marbridgedaily/archive/article/32185/china_prohibits_vegetable_stealing_in_sns_games

After that, I'm still somewhat in the dark about vegetable stealing.

aaron said,

April 26, 2011 @ 7:36 pm

#5 is spurious. "QQ" has nothing to do with quitting the program, and refers only to the crying-face emoticon. "qq more noob" is the basic and most common expression of this usage.

Bruce said,

April 26, 2011 @ 7:37 pm

The vegetable stealing is for Farmville-type social networking games.

As xkcd notes: "Best trivia I learned while working on this: 'Man, Farmville is so huge! Do you realize it's the second-biggest browser-based social-networking-centered farming game in the WORLD?' Then you wait for the listener to do a double-take."

http://xkcd.com/802/

y said,

April 26, 2011 @ 8:29 pm

I remember a few years ago when Taiwanese newspapers were creating a hubub for their use of the suffix "-ing" at the end of Chinese verbs. I haven't actually seen it proliferate, though– I wonder how tenacious these additions actually are.

Anne Henochowicz said,

April 26, 2011 @ 8:45 pm

I think "-er" is used in the cartoon exactly as 者 would, hence no plural. It's an English morpheme with a Chinese equivalent, obeying the rules of Chinese.

Tezuk said,

April 26, 2011 @ 9:02 pm

Y,

The ING is actually very common in Taiwan now. It is very strange, as when I have heard people use this in spoken Chinese, they spell out the letters e.g. 打滾-I-N-G

See 五月天's MV for numerous examples:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3CBp74HXpYM

Ethan said,

April 26, 2011 @ 9:03 pm

Chinese and English also beat out competitors to become the future of standard interstellar communication in the first and only season of "Firefly."

neminem said,

April 26, 2011 @ 9:21 pm

Yeah. My first thought about QQing was also WoW, and I will agree with previous comments that it's merely a logical extension of #4, "QQ"ing having been turned into a verb meaning, roughly, "to throw a pointless hissyfit over something dumb". Not particularly related to the rest of this discussion, but it *is* fairly interesting seeing what was originally an unpronouncable emoticon get turned into a verb (spoken "cue cue").

And of course, as mentioned immediately above, I also hope you've seen Firefly, it having done a pretty shiny job of showing a verse where people speak English+Chinese. (Apparently if you speak fluent Chinese, you can tell that the actors have just memorized their Chinese lines, and don't actually speak any Chinese. I don't speak fluent Chinese.)

Lareina said,

April 26, 2011 @ 10:10 pm

I really want to see China Babel :DDDD

It should be Animal Farm in the linguistic world

Q——-Q (this is the whole emoticon that means crying)

Leonardo Boiko said,

April 26, 2011 @ 10:33 pm

Please do publish China Babel.

mondain said,

April 26, 2011 @ 11:26 pm

The '-er' suffix here is more than a borrowed morpheme from English meaning '者'. It may well be a suffix indicating 儿化音, esp. in the cases of 豆瓣儿, 人人儿.

Bob Violence said,

April 27, 2011 @ 5:13 am

The -ing suffix also pops up a lot in (mainland) China, not only in the expected places (online writing, text messages) but also in advertising. One use I noticed recently was in an ad for Subway restaurants, although I can't recall the specific context.

Thor Lawrence said,

April 27, 2011 @ 6:10 am

Just to confuse the issue, the -er morpheme is traditional school argot at one English public [i.e. fee-paying] school — a school that has established a satellite school in Beijing. Alumni spreading the word?

Victor Mair said,

April 27, 2011 @ 6:44 am

I'm happy to get all of the confirmation about the lasting power of -ing (which I first noticed a couple of years ago) and the spreading of -er.

mondain raises an interesting possibility, namely, that the -er ending might reflect the penchant for adding a retroflex ending to words that is prominent in many northern topolects (especially Pekingese, of course). I had actually briefly considered that possibility, but ultimately dismissed it for a number of reasons, including these:

1. it wouldn't go with "SNS" in the title or with "Facebook" in the body of the text

2. the -er ending fits better in all of the instances where it occurs in this text as indicating an actor, agent, or habitué rather than as a retroflex ending

Still, I'm glad that mondain brought up the possibility that Roman letter "-er" (as such) might sometimes be used for the sinographic 儿 ending. I wouldn't be surprised if it sometimes happens. Indeed, what is most intriguing, and this may be what mondain was really pointing at, is that the new -er morpheme in Mandarin may sometimes simultaneously be pronounced and analyzed by some speakers as retroflexion.

mondain said,

April 27, 2011 @ 7:29 am

@Victor Mair: I agree with both reasons you listed above.

I didn't notice '三里屯er' in facebooker's profile, which is more naturally a retroflex ending, but explicitly spelt out to express the sense of 'habitué'.

Ellen K. said,

April 27, 2011 @ 9:16 am

I can't read the Chinese in Mondain's post, now do I understand what's meant by a retroflex ending. Can someone fill me in?

Ellen K. said,

April 27, 2011 @ 9:25 am

I can't read the Chinese in Mondain's post, nor do I understand what's meant by a retroflex ending. Can someone fill me in?

Adam said,

April 27, 2011 @ 11:01 am

Is there no way to create new Chinese characters for new morphemes?

cntrational said,

April 27, 2011 @ 11:35 am

@Ellen K.: Some variants of Mandarin Chinese have an "-er" sound at the ends of syllables, pronounced [ɻ], the retroflex approximant. This is known as "erhua", and is most common in Northern dialects, and can be found to an extent in the Standard dialect.

Ellen K. said,

April 27, 2011 @ 12:50 pm

Still awaiting an explanation of Mondain's post about "er" meaning something.

Damon said,

April 27, 2011 @ 1:06 pm

Is "Wei Aihua" a sinicization of an English name? Because it sure seems odd to call someone that and specify that he's British.

cntrational said,

April 27, 2011 @ 1:28 pm

Ellen K.: Oh, uh, right, sorry; some dialects use erhua for grammatical purposes: Beijing Mandarin, for example, uses it to indicate diminutives. And erhua may be used for the new -er suffix.

richard said,

April 27, 2011 @ 4:26 pm

@Damon, the British guy's name could be translated (crudely) as "We Love China." I would guess that his traits are more those of a certain slice of expaits living in Beijing than anything specifically British.

Eric said,

April 27, 2011 @ 4:33 pm

Not knowing any Mandarin but having read "Beijing Sounds," it wasn't 'til I read Mair's analysis that I parsed -er as a suffix meaning "person who does X" as opposed to 儿.

@Ellen K.

"Does the Beijing -er Mean Anything?"

Chris Holdaway said,

April 27, 2011 @ 8:27 pm

A friend of mine mentioned the character 者 (zhĕ) which I see some other have brought up. Apparently it's the same as English -er, deriving a noun from a verb that denotes a person who does the action described by the verb.

听 (tīng) – listen

听者 (tīngzhĕ) – listener, someone who listens

She seemed to think that 者 (zhĕ) could only be applied to verbs not nouns, and -er is the same really. Prototypically a derivational suffix only for verbs, the application to nouns is now common, but I'd imagine still considered 'non-standard' to some degree by a great many people.

This is really interesting though, seeing incorporation of English into Chinese that is grammatical, not just lexical.

Apologies if any of the Chinese is wrong… I have never studied it, and am going off some quickly scrawled hand-written notes which I can only hope I am reading accurately.

C.

Chris Holdaway said,

April 27, 2011 @ 8:34 pm

Qualifying the above:

With place names and proper nouns, -er wouldn't be non-standard at all. Didn't think about that at the time, and I suppose in some way the names of social networking sites are all proper nouns.

Caio said,

April 28, 2011 @ 5:37 am

Erg, I go on the internet to get away from chinese stereotypes of foreigners.

The Zhongnanhai one made me shudder. Nothing like walking into a store and having the clerks laughingly insist I buy Zhongnanhai and coca-cola.

Jerome Chiu said,

April 28, 2011 @ 5:52 am

The use of "-er" has for a long time been very popular in Chinglish, sometimes pushing it to quite absurd levels, e.g. In the anime Springfield Flower Flower Kindergarten Alumni Association, classmates of McDull would like to become not only doctors, lawyers and chief executive officers but also "cappuccino brrrrrrrrrrrrrr-ers" and "chicken claw lun-lun-lun-lun-lun-ers":

http://youtu.be/1nVGb2KZd94

minus273 said,

April 28, 2011 @ 10:27 am

-er may be an equivalent to "者", but "者" won't work here. Possible suffixes to -er could be "男" (male), "青年" (youth), "控" (fan < complex) or "党" (party). "族" is too old-fashioned.

B.Ma said,

April 28, 2011 @ 1:43 pm

I suppose you could say something like Facebook使用者 instead of just 者, which makes it far easier to say "er".

jjatria said,

April 28, 2011 @ 2:00 pm

This might be a little far from the topic at hand, but I've seen something very similar to this when I went on a short visit to Hong Kong some months ago, although involving different languages.

While walking on the streets with some friends, we stumbled on a number of signs on the street that used the japanese "の" like the english "'s" at the end of some nouns to indicate possession (or at least what I can imagine were nouns, since I know nothing of Cantonese).

Sadly, I don't have any pictures of the relevant signs, but I was told by a local friend that it had become a somewhat popular practice recently. Has anybody else seen or heard anything about this, or practices like this?

ohwilleke said,

April 28, 2011 @ 2:55 pm

"About 15 years ago, I wrote a science fiction novel called "China Babel" (still unpublished) in which I described a time in the future when Chinese would merge with English."

Ethan is on point here in his Firefly/Serenity reference. Indeed, this science fiction world in addition to leaving the two languages dominant does show some limited Spanglish style language merger. For example, English speaking characters curse in (ideomatic modern) Chinese.

Chris Holdaway said,

April 28, 2011 @ 4:06 pm

@minus273

The same friend I mentioned in my above post had a further think, and gave me some instances where 者 does modify a noun (or adjective).

正义 (zhèng yì) – justice, just

正义者 (zhèng yì zhĕ) – a just person, a person with a sense of justice

长 (zhăng) – old

长者 (zhăng zhĕ) – elder, an eldery person

So it would seem that 者 is not quite equivalent to the English -er derivational suffix. But in nay case, my friend agreed that it would not work in the cases of people who use social networks.

minus273 said,

April 29, 2011 @ 5:48 am

I think the problem is that the SNS's are considered as place names, which is why we can say "Doubaner" in English (à la "Dubliner", "Berliner" …) but not "豆瓣者" in Chinese (because we say "北京人", "北京青年" etc.)

Eric Vinyl said,

May 4, 2011 @ 4:23 pm

@jjatria

It's mentioned/documented in Languages of Hong Kong on Wikipedia. Apparently it's pronounced jì.

Niku said,

June 11, 2011 @ 11:10 pm

@jjatria

I'd bet it's an import from Taiwan – many many Taiwanese people substitute の for 的 when taking notes (because it's much faster that way). The first time I saw this, I did a huge double-take. It's extremely common to see this kind of stuff on street signs, store names, etc, but to see it coming out of somebody's pen was quite a shock.

One friend mentioned that she was taught that way in elementary school. I'd be really curious to know if that's true or common!