Strange prescriptions

« previous post | next post »

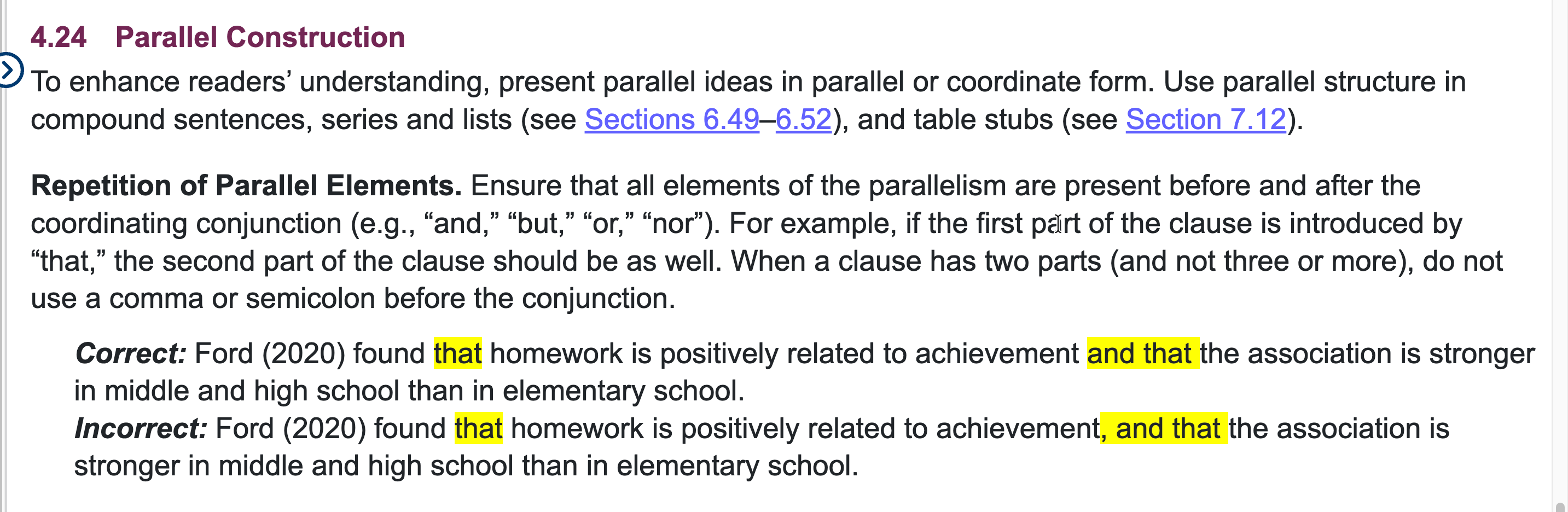

An email recently informed me that the American Psychological Association has created an online version of the APA Style Guide (technically the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Seventh Edition, and that Penn's library has licensed it. A quick skim turned up a prescriptive rule that's new to me, forbidding the use of commas to separate conjoined that-clauses unless there are at least three of them:

This seems to be a generalization of the "serial comma" principle, which prescribes commas to separate "elements in a series of three or more items". And it's sensible enough to use commas in "yesterday, today, and tomorrow", but not in "yesterday, and today".

But generalizing this advice to conjunctions of that-clauses strikes me as wrong: a tone-deaf prescription, opposed by common sense as well as by a long history of contrary usage.

A trivial search in William James' Principles of Psychology turned up several hundred "incorrect" examples. Here are the first few from Volume I:

However firmly he may hold to the soul and her remembering faculty, he must acknowledge that she never exerts the latter without a cue, and that something must always precede and remind us of whatever we are to recollect.

They find that excision of the hippocampal convolution produces transient insensibility of the opposite side of the body, and that permanent insensibility is produced by destruction of its continuation upwards above the corpus callosum, the so-called gyrus fornicatus (the part just below the 'calloso-marginal fissure' in Fig. 7).

Wider and completer observations show us both that the lower centres are more spontaneous, and that the hemispheres are more automatic, than the Meynert scheme allows.

But Schrader, by great care in the operation, and by keeping the frogs a long time alive, found that at least in some of them the spinal cord would produce movements of locomotion when the frog was smartly roused by a poke, and that swimming and croaking could sometimes be performed when nothing above the medulla oblongata remained.

And from Volume II:

They tell us that the relation of sensations to each other is something belonging to their essence, and that no one of them has an absolute content.

Helmholtz maintains that the neural process and the corresponding sensation also remain unchanged, but are differently interpreted; Hering, that the neural process and the sensation are themselves changed, and that the 'interpretation' is the direct conscious correlate of the altered retinal conditions.

Hering shows clearly that this interpretation is incorrect, and that the disturbing factors are to be otherwise explained.

It can, however, easily be shown that the persistence of the color seen through the tube is due to fatigue of the retina through the prevailing light, and that when the colored light is removed the color slowly disappears as the equilibrium of the retina becomes gradually restored.

It's equally easy to find examples from other eras, other authors, and other publishers. Here are a few examples from Bertrand Russell's Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy:

But this presupposes that we have defined numbers, and that we know how to discover how many terms a collection has.

It is very easy to prove that 0 is not the successor of any number, and that the successor of any number is a number.

We now know that all such views are mistaken, and that mathematical induction is a definition, not a principle.

Although various ways suggest themselves by which we might hope to prove this axiom, there is reason to fear that they are all fallacious, and that there is no conclusive logical reason for believing it to be true.

Why did the APA take this weird prescriptive step? It seems to be one of many cases where style guides are led astray by false logic.

wgj said,

November 8, 2025 @ 7:20 am

Looks like a typical case of one person (whoever wrote that rule into the guide) trying to impose their fringe personal preference onto the world.