The end of "Teaching Lucy"?

« previous post |

Helen Lewis, "How one woman became the scapegoat for America's reading crisis", The Atlantic 11/13/2024:

Lucy Calkins was an education superstar. Now she’s cast as the reason a generation of students struggles to read. Can she reclaim her good name?

Until a couple of years ago, Lucy Calkins was, to many American teachers and parents, a minor deity. Thousands of U.S. schools used her curriculum, called Units of Study, to teach children to read and write. Two decades ago, her guiding principles—that children learn best when they love reading, and that teachers should try to inspire that love—became a centerpiece of the curriculum in New York City’s public schools. Her approach spread through an institute she founded at Columbia University’s Teachers College, and traveled further still via teaching materials from her publisher. Many teachers don’t refer to Units of Study by name. They simply say they are “teaching Lucy.”

But now, at the age of 72, Calkins faces the destruction of everything she has worked for. A 2020 report by a nonprofit described Units of Study as “beautifully crafted” but “unlikely to lead to literacy success for all of America’s public schoolchildren.” The criticism became impossible to ignore two years later, when the American Public Media podcast Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong accused Calkins of being one of the reasons so many American children struggle to read. (The National Assessment of Educational Progress—a test administered by the Department of Education—found in 2022 that roughly one-third of fourth and eighth graders are unable to read at the “basic” level for their age.)

The whole article is worth reading, and may help readers understand why reading instruction remains both cult-ridden and disappointingly unsuccessful.

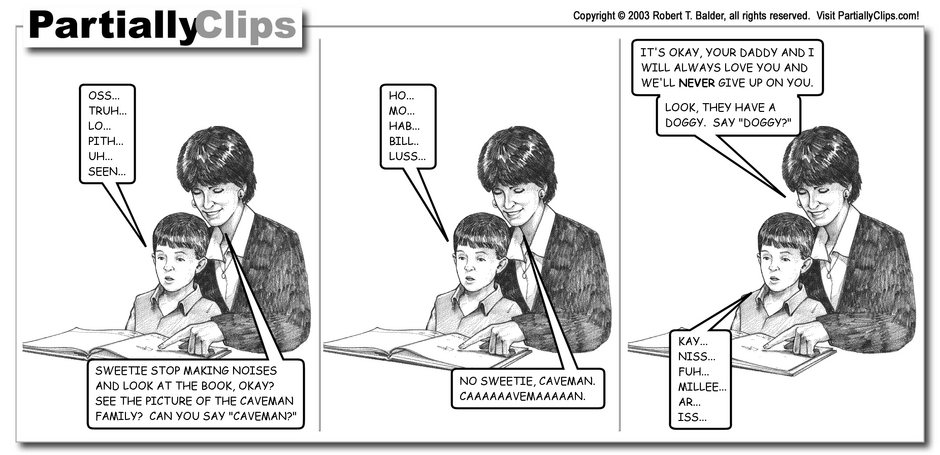

This would also be a good time to reprint this 2003 Partially Clips cartoon:

That cartoon was mainly aimed at the pre-Calkins "Whole Language" ideology, though the Atlantic article quotes several critics who characterize Calkins' system as "a strategic rebadging of whole language”.

If you're interested in a deeper dive into the current situation and trends in U.S. reading instruction, see Foster et al., "On the Same Page — A Primer on the Science of Reading and Its Future for Policymakers, School Leaders, and Advocates", Bellwether 2024:

Reading is a life-transforming and essential skill. It does not come naturally; it must be taught. Nearly all children have the capability to learn to read, with the right teaching and support. And yet, just 32% of fourth-grade students achieved reading proficiency in 2022.

If you prefer to watch and listen, the same material is available as a webinar on YouTube.

I should note that I'm a co-PI for the new Using Generative AI for Reading R&D Center, which is just being set up — so you can expect more posts on this topic as things develop.

Some relevant past posts:

"Ghoti and choughs again", 8/16/2008

"Why isn't English a Bar Mitzvah language?", 8/19/2008

"The science and politics of reading instruction", 8/17/2012

"The Gladwell Pivot", 10/28/2013

"Faimly Lfie", 6/21/2017

"Julie Washington on Dialects and Literacy", 5/21/2018

Jerry Packard said,

November 20, 2024 @ 9:40 am

In my pre-retirement role as a professor of Chinese, linguistics and Ed Psych, my colleagues, students and I were involved in reading instruction and research – Chinese kids learning Chinese in China, and undergrads learning Chinese in the US – for many years.

The two most common methods for teaching reading at the time were ‘whole language’ (i.e., sight word reading) and phonics. Over the years there has been a lot of tension between the whole language and phonics camps, as exemplified in the Partially Clips cartoon.

In my experience, I observed that most of us are naturally sight readers, while some of us have an easier time with phonics. My recollection is that most kids who had problems learning to read with whole language instruction benefitted from a greater focus on phonics. I found this to be true in learning to read Chinese (both as L1 and as L2), except that, comparatively speaking, it took longer exposure to Chinese (e.g., 3 years or more) than English for a student to effectively rely on phonics. That’s because the Chinese phonetic radicals do not reliably reflect pronunciation, especially in the high-frequency, first-encountered characters. This means that learning to read Chinese requires exposure to a lot more characters (maybe 1-2 thousand) before the phonetic regularities in the characters begin to become apparent to the learner.

I do not have a particular point to make except maybe to agree that children do learn reading best when they love reading, and that teachers should try to inspire that love by making materials available and using them often

Philip Taylor said,

November 20, 2024 @ 9:51 am

[I may have stated the following facts in a previous comment, in which case I apologise for repeating myself].

My parents (particularly my mother) taught me to read long before I started school, and she used what was then known in the U.K. as the "look-say" method, which I now believe to be the same as "whole language". I then attended a number of schools (my family moved house regularly), some of which used "look-say" while the others used phonics. I found the latter incredibly frustrating, as my mother had not only taught me to read but had also taught me the whole (English) alphabet, in both directions (ZYX and WV, UTS and RQP, ONM and LKJ, IHG, FED and CBA), so being forced to pronounce "A" as /æ/ I found complete anathema (and protested accordingly).

bks said,

November 20, 2024 @ 10:07 am

I was in charge of the "Scholastic Book Club" for my daughter's kindergarten class. There was already a bifurcation in the class of those kids who already knew the alphabet and many words, and those who did not. I attributed this to parents who had the time and inclination to stress the importance of reading to their children. I was astounded to meet parents who didn't read books at all, let alone read books to their children. (c. 1990)

J.W. Brewer said,

November 20, 2024 @ 10:25 am

It's not just reading instruction – there have been lots of transient bad-idea fads in math instruction in American K-12 schooling over the last few generations, although the unsatisfactory output of bad math instruction is easier to measure quantitatively and thus harder for the bad-idea advocates to handwave away as missing the point. Something is structurally/sociologically wrong with the schools of education faculty that makes them particularly prone to clever new ideas that end up making things worse in practice whereas e.g. the schools of engineering faculty are better at focusing on clever new ideas that may or may not work but at least accept and try to improve on what has already been shown to work rather than discard it and risk technological regression.

A related structural issue may be that lots of U.S. public school districts have some bureaucrat with a job title like Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum Development or something like that, and those bureaucrats are incentivized to push for a random and radical change in how the district teaches some subject (doesn't matter which subject) every couple of years, because anyone in that position who takes an "if it ain't broke don't fix it" approach will raise questions of whether their job and its associated salary is justified.

Philip Taylor said,

November 20, 2024 @ 10:39 am

BKS — "I attributed this to parents who had the time and inclination to stress the importance of reading to their children" — I would query "the importance" : my mother never taught me the importance of reading, she simply taught me (and encouraged me) to read for pleasure. I still treasure two of the books she and my father gave me — Coral Island (tho' I recoiled then, and still recoil to this day, at the scene in which a cat is whirled around someone's head by its tale and then thrown far out to sea …) and Tom Brown's Schooldays. Later on she became a little censorious over my choice of reading matter, and was none too impressed by my bringing home (probably from jumble sales) Roses of Martyrdom and Virtues' Household Physician. I'm fairly sure that she also confiscated the copy of Pilgrim's Progress that I had found in an "aunt's" house while visiting at around the age of eight and which I had immediately started reading (scare quotes around "aunt" because British children at that time tended to have rather more aunties and uncles than could actually claim any genetic connection). Those being pre-PC, pre-woke times, however, she had no problem with giving me a copy of The Story of Little Black Sambo which I vividly remember reading on a train at about the age of six while going to the seaside.

Philip Taylor said,

November 20, 2024 @ 12:22 pm

P.S. I was unfamiliar with "PartiallyClips" prior to this post, but having just trawled through the archive I cannot miss the opportunity to note this one — https://web.archive.org/web/20070710140545im_/http://www.partiallyclips.com/storage/dentist_lg.png