Steele v. Monboddo

« previous post | next post »

In "AI win of the week" I explored the inter-personal dimensions of Rousseau's 1754 contention that "there is neither rhythm nor melody in French music, because the language is not capable of them". In the comments, AntC objected that "But, but. Rousseau wrote an opera, in French, to his own Libretto. audio + full score available on Youtube".

For now, I have only two comments on this. First, trolls are often happy to abandon consistency in the service of pwning their audience. And second, the 1754 edition of Rousseau's screed, published two years after the debut of his opera, goes into considerable detail about how he painfully transferred the musicality of Italian prosody to the composition and performance of a work with French lyrics.

But rather than diving further into Rousseau's argument about the relative musicality of different languages' prosody, the point of today's post is to note its resonance with another mid-18th century prosodic dispute, namely Joshua Steele's refutation of James Burnett's claim that English prosody gives its syllables "nothing better than the music of a drum, in which we perceive no difference except that of louder or softer, according as the instrument is more or less forcibly struck".

My connection with this argument began in 1973, when I was trying to learn something about English intonation. The (very small) relevant section of the stacks in MIT's library happened to have (a facsimile edition of) Steele's 1775 work, An Essay Towards Establishing the Melody and Measure of Speech to be Expressed and Perpetuated by Peculiar Symbols. I read it carefully and learned a lot.

One of the first things I learned was Steele's motivation for the enterprise. His description starts this way:

[M]y learned and honoured friend Sir John Pringle, President of the Royal Society, desired me to give him, in writing, my opinion on the musical part of a very curious and ingenious work lately published at Edinburgh, on The Origin and Progress of Language, which I should find principally in part II. book ii, chap. 4. and 5. wherein several propositions, denying that our language has either the melody of modulation, or the rhythmus of quantity, gave occasion to the following systematic attempt to prove the contrary.

At that point I paid no further attention to Monboddo's "very curious and ingenious work", partly because I was convinced by Steele's arguments against it, and partly because the library didn't have a copy of (any of the six volumes) of the work in question. But digital facsimiles are now easy to come by, and so I've taken a look at the stuff that led Pringle to question Steele, and led Steele to write his essay.

The author was James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (see Language Hat's post on the interpretation of the name), and the six volumes of The Origin and Progress of Language were published between 1774 and 1792. Volume II was part of the initial 1774 publication, giving Steele only a year to prepare and publish his response a year later.

The relevant pages of Monboddo's work are here, if you really want to slog through them. The critical passage comes at the end:

But what do we mean then when we speak so much of accent in English, and dispute whether a word is right or wrong accented? My answer is, That we have, no doubt, accents in English, and syllabical accents too: but they are of a quite different kind from the antient accents ; for there is no change of the tone in them; but the voice is only raised more, so as to be louder upon one syllable than another. Our accents therefore fall under the first member of the division of sound, which I made in the beginning of this chapter, namely, the distinction of louder, and softer, or lower.

That there is truly no other difference, is a matter of fact, that must be determined by musicians. Now I appeal to them, whether they can perceive any difference of tone betwixt the accented and unaccented syllables of any word; and if there be none, then is the music of our language in this respect nothing better than the music of a drum, in which we perceive no difference except that of louder or softer, according as the instrument is more or less forcibly struck.

Of course Monboddo is also wrong that drum sounds can differ only in loudness and not in frequency content — watch and listen here for a refutation, or here for another (and more linguistically relevant) one.

But in fairness to Lord Monboddo, his "English accents are like drum beats" claim is not quite so idiotically tone-deaf as it seems, since he makes two other claims earlier that fuzzify it somewhat. One is the idea that English pitch changes exist, but only as "the tones of passion or sentiment":

As to accents in English, Mr Foster, from a partiality, very excusable, to his country, and its language, would fain persuade us, that in English there are accents such as in Greek and Latin. But to me it is evident that there are none such; by which I mean that we have no accents upon syllables, which are musical tones, differing in acuteness or gravity. For though, no doubt, there are changes of voice in our speaking from acute to grave, and vice versa, of which a musician could mark the intervals, these changes are not upon syllables, but upon words or sentences. And they are the tones of passion or sentiment, which, as I observed, are to be distinguished from the accents we are speaking of.

And he adds

[T]here is another difference betwixt our accents and the antient, that ours neither are, nor can, by their nature, be subjected to any rule ; whereas the antient, as we have seen, are governed by rules, and make part of their grammatical art.

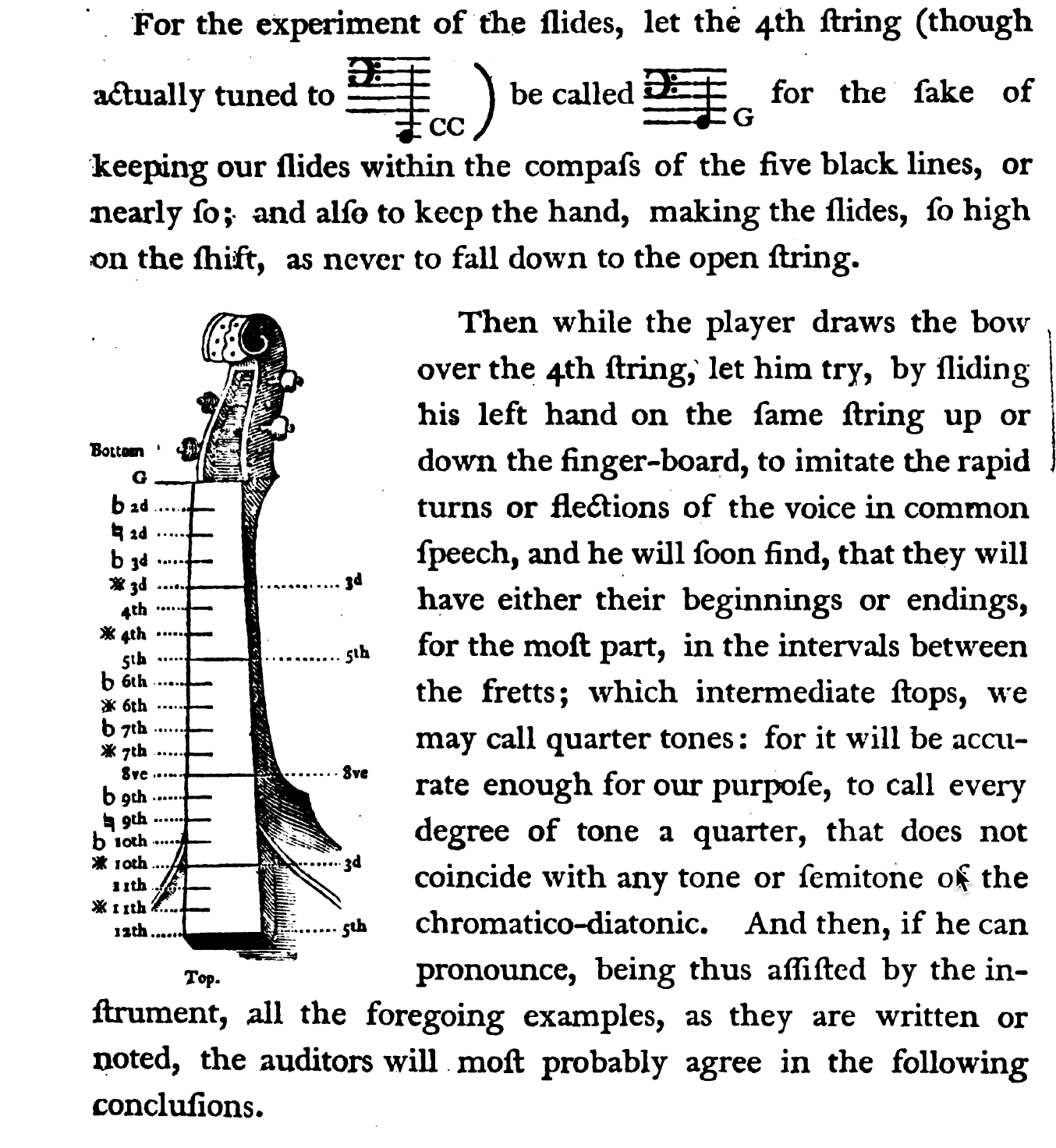

Anyhow, Steele took it on himself not only to show that English had "melody and measure", but also to provide "peculiar symbols" for expressing it. The pages where he introduces his notation are here. His instrumental analysis method — using a bass viol — is better than any other one that would be available for the following couple of hundred years:

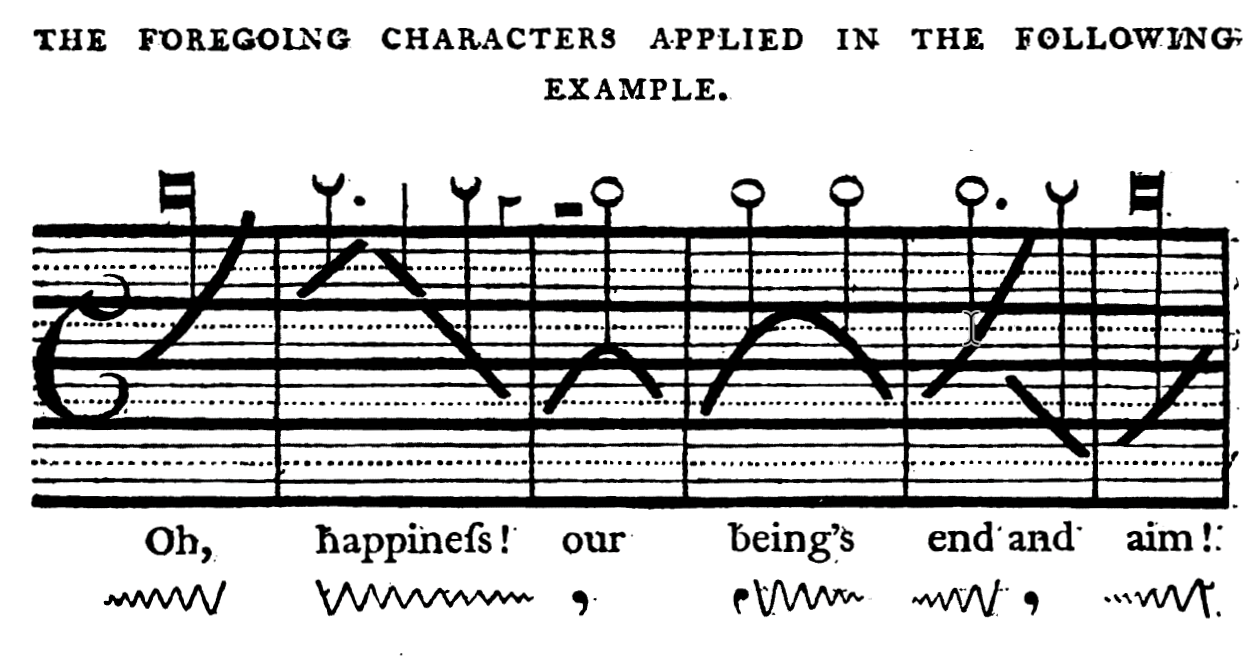

Along with some other notational inventions, the result is transcriptions like this:

And his conclusions:

1st, That the sound or melody of speecb is not monotonous, or confined like the found of a drum, to exhibit no other changes than those of loud or soft.

2dly, That the changes of voice from acute to grave, and vice versa, do not proceed by pointed degrees coinciding with

the divisions of the chromatico-diatonic scale; but by gradations that seem infinitely smaller (which we call slides); and though altogether of a great extent, are yet too rapid (for inexperienced ears) to be distinctly sub-divided; consequently they must be submitted to some other genus of music than either the diatonic or chromatic.

3dly, That these changes are made, not only upon words and upon sentences, but upon syllables and monosyllables. Also,

4thly, and lastly, That in our changes on syllables or monofyllables, the voice slides, at least, through as great an extent as the Greeks allowed to their accents; that is, through a fifth, more or less.

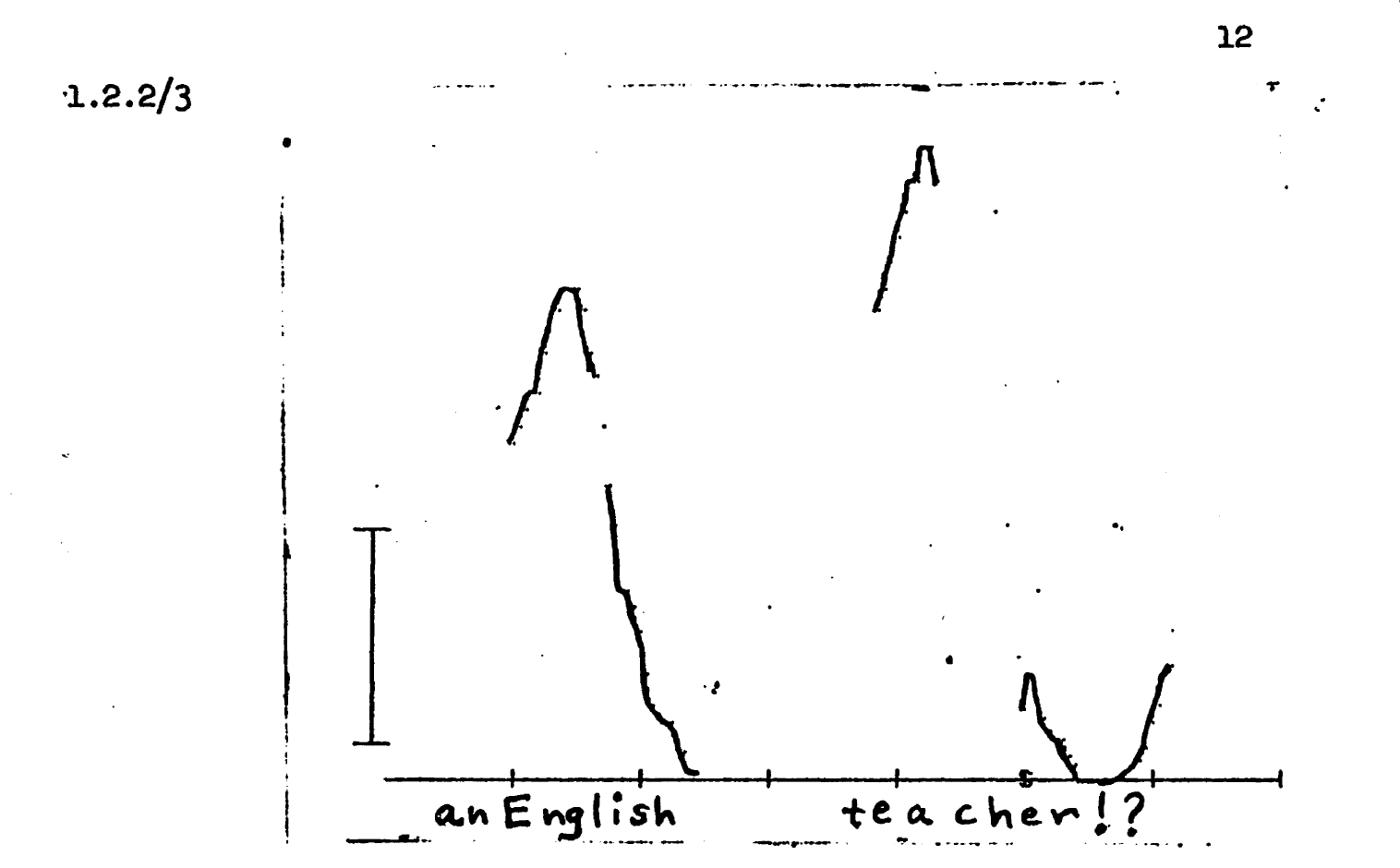

Not having access to a bass viol, I followed Steele's example using a computer program for a PDP-9, allowing figures like this one from my 1975 dissertation:

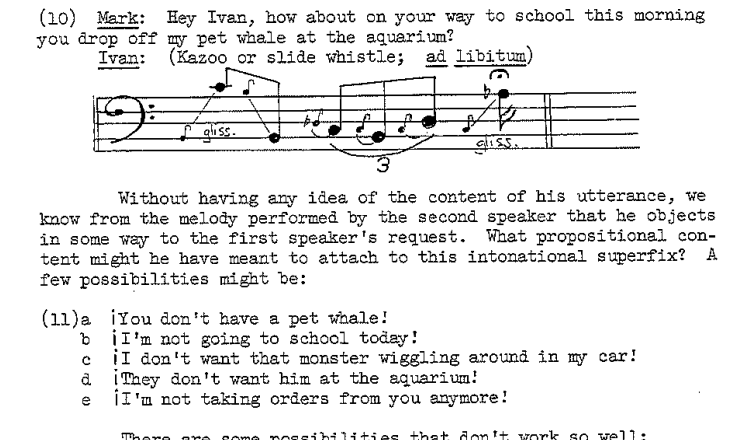

Though for presentational purposes, Ivan Sag used a kazoo in presentations like this one:

Jerry Packard said,

July 12, 2025 @ 12:38 pm

And of course it must be said that since then scholars such as Dwight Bolinger, Bob Ladd and Mark Liberman have given us exquisite treatments of English intonational patterns.

Chris Button said,

July 12, 2025 @ 1:41 pm

@ Jerry Packard

Don't forget the storied history of English phonetics at University College London.

One of the things I really appreciated about SOAS was that UCL's troves were right next door.

David Marjanović said,

July 12, 2025 @ 1:47 pm

Just for the record, there are languages like that. Some people speak Finnish this way.

Others have high pitch for stressed ( = word-initial) and low pitch for unstressed syllables, for a total of two pitches. This also occurs in Hungarian; other speakers of Hungarian add a third pitch for sentence-level stress or so.

At the other end of the scale, English intonation routinely does things that would, in German or most of it, count as singing rather than speaking.

Mark Liberman said,

July 12, 2025 @ 2:24 pm

@David Marjanović "Just for the record, there are languages like that. Some people speak Finnish this way. […] This also occurs in Hungarian.":

Please provide links to some realistic examples — this is not consistent with what I've seen in analyzing Finnish and Hungarian.

Stephen Bowden said,

July 12, 2025 @ 4:49 pm

The BBC children’s series The Clangers demonstrates how English can be communicated almost solely by musical pitch. The eponymous creatures communicate by Swanee whistle but the meaning is clear, and there were even complaints that some of their conversations included obscenities.

Jonathan Smith said,

July 12, 2025 @ 4:59 pm

Through a modern lens darkly and generously, I suppose Burnett might be understood to be claiming that English words feature only stressed or unstressed syllables; i.e., to be anticipating phonemic analyses that feature only one degree of stress. This makes some sense as a rough-and-ready account of what made e.g. Ancient Greek "pitch accent" so different (English-speaking learners of e.g. Japanese can relate)… though IDK how this system (or whatever parallel system [might have] existed in Classical Latin) was understood or taught back in the day.

KevinM said,

July 12, 2025 @ 5:13 pm

For a more modern and virtuosic example of speech-musical pitch equivalence, check out Mononeon: https://youtu.be/nQJeNl0b8g0 .

JPL said,

July 12, 2025 @ 5:37 pm

With regard to the question of the musicality of a language's prosody and Steele's refutation of Monboddo's claim about English, I've always liked late 80s-early 90s hip hop for the musicality of its lyrical speech-rhythms and prosody, stress-timing and lengthening of syllables, etc. I always wonder how this would have been received in early 20th century England, in spite of the innovations of Hopkins and his "sprung rhythms". In any case, it's time for summer madness!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kr0tTbTbmVA

Richard Rubenstein said,

July 12, 2025 @ 10:44 pm

With (precisely) due respect to Sapir and Whorf, I propose Rubenstein's Rule: By carefully studying the properties of a particular language, we can learn a great deal about the character and mode of thought of the person conducting the study.

Yves Rehbein said,

July 13, 2025 @ 12:57 am

Related: cf. "In Springfield" at the bottom https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=66001

AntC said,

July 13, 2025 @ 2:31 am

Delibes' "Sous le dôme épais" (Flower Duet) seems to be eternally popular, though not as famous as "Air des clochettes" (Bell Song) alleges wikip. Or does Lakmé not count because set in India? Debussy's Pelléas and Mélisande ain't too shabby, either. Perhaps we had to wait until thoroughly past the Baroque metronome regimen for French prosody to flourish in music?

Robert Coren said,

July 13, 2025 @ 9:41 am

As a trained (although strictly amateur) classical singer, I've had occasion to sing lots of music in English, French, German, and Italian, and my experience is that all of them are perfectly well suited for singing, although their different characteristics will generally inform the character of any particular song or aria.