This 'n that

« previous post | next post »

A recent Elle Cordova short:

Many aspects of this skit deserve linguistic analysis — I'll focus on on two things:

- The semantic step from literal "this and that", referring to two specific things, to an expression that Wiktionary glosses as referring to "various unspecified things".

- The cross-linguistic variation in degrees of distance contrast in demonstratives.

WRT point (1), Wiktionary has no pages for ceci et cela or dit en dat or dies und das or esto y aquello — I'm not clear whether that's because the expressions are less (or not at all) colloquial in French and Dutch and German and Spanish etc., or just because those Wiktionary sections are less populated. Certainly a few examples can be found on line, e.g. the name of a grocery store in Toulouse… Reactions from readers will be appreciated, extending to whatever other languages you know.

There's a passage in St. Augustine's Confessions suggesting that a version of the analogous idiom existed in 4th century Latin:

(26) Retinebant nugae nugarum et vanitates vanitantium, antiquae amicae meae, et succutiebant vestem meam carneam et submurmurabant, “dimittisne nos?” et “a momento isto non erimus tecum ultra in aeternum” et “a momento isto non tibi licebit hoc et illud ultra in aeternum.” et quae suggerebant in eo quod dixi “hoc et illud,” quae suggerebant, deus meus, avertat ab anima servi tui misericordia tua! quas sordes suggerebant, quae dedecora! et audiebam eas iam longe minus quam dimidius, non tamquam libere contradicentes eundo in obviam, sed velut a dorso mussitantes et discedentem quasi furtim vellicantes, ut respicerem. tardabant tamen cunctantem me abripere atque excutere ab eis et transilire quo vocabar, cum diceret mihi consuetudo violenta, “putasne sine istis poteris?”

(27) Sed iam tepidissime hoc dicebat. aperiebatur enim ab ea parte qua intenderam faciem et quo transire trepidabam casta dignitas continentiae, serena et non dissolute hilaris, honeste blandiens ut venirem neque dubitarem, et extendens ad me suscipiendum et amplectendum …

(26) My old friends, utter frivolity and complete vanity, were restraining me. Beneath my garment of flesh they were pinching me gently and whispering softly, “Are you going to send us away?” and, “from that moment we shall no longer be with you forever” and, “from that moment you will not be allowed to do such and such ever again.” As for the things they were reminding me of, in that “such and such” I just referred to, what they were reminding me of, O my God, let your mercy turn it aside from the soul of your servant! What filth, what shame they were reminding me of! I was not even half-listening to them, and they no longer argued with me in an open attack. Instead they were grumbling behind my back and, as it were, furtively nagging me, even as I was abandoning them, to look back. They slowed me down as I hesitated to snatch myself away from them and shake them off, and to make the leap to where I was being called; for my impetuous habits kept calling to me, “Do you think you can cope without those things?”

(27) But that call of habit was now barely lukewarm, for from the direction where I had turned my face, and where I trembled to move across, there appeared the pure excellence of Chastity. She was tranquil rather than carelessly merry, she was frankly coaxing me to come on and not hesitate, she held out holy hands to support me …

(English translation by Carolyn J.-B. Hammond. It seems to me that "this and that" would work as well as "such and such" to translate Augustine's "hoc et illud", but the general idea is clear either way.)

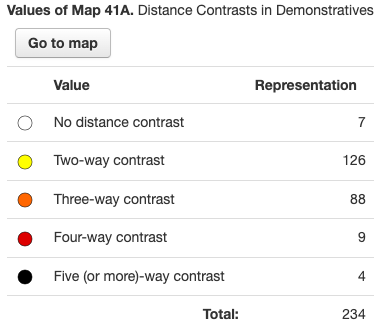

Moving on to point (2), we note that the World Atlas of Language Structures distinguishes at least five type of "Distance Contrasts in Demonstratives":

I have some personal experience with one four-way contrast language, namely Somali, based on a field-methods course from which I took a simple morphology exercise for ling001 (see section 3(b)…). But I don't know whether Somali has a way of combining some of these demonstratives to make an idiom meaning "various unspecified things".

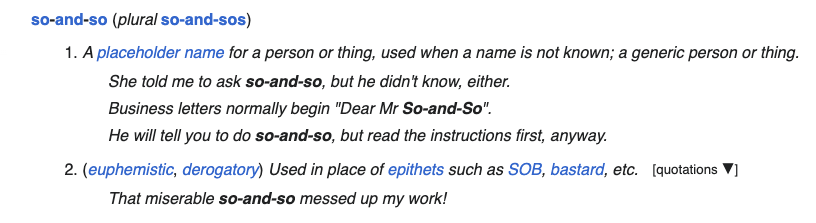

Update — Note that "so-and-so", in addition to normally being hyphenated, has a possible derogatory meaning, which Wiktionary gives as a second gloss:

But Elle Cordova's use of "so-and-so" in the cited skit is laudatory rather than derogatory.

"Such-and-such" has no analogous derogatory extension.

JimG said,

December 14, 2024 @ 7:10 pm

You sent me off on tangents:

AmEnglish commonly uses a 3-way expression, "this, that, and the other."

Spanish "tal y tal" translates as so-and-so (as in "he's such a so-and-so", or as in such-and-such.)

There are various languages that use a triplet for unspecified persons (e.g. Tom, Dick and Harry, or Spanish: Fulano, Mengano y tal)

Laura Morland said,

December 14, 2024 @ 9:46 pm

Re: "Wiktionary has no pages for ceci et cela …. I'm not clear whether that's because the expressions are less (or not at all) colloquial in French.

You nailed it. French people don't say "ceci et cela". (And in fact, they don't often say "ceci" these days, and "cela" is usually shortened to "ça".)

The one believable translation I was able to locate of "this and that" in French is the following:

Plus le soleil baisse plus je me sens bien seul sous mon casque a réfléchir à tout et à rien.

More the sun sets and more I feel good alone in my helmet to think of this and that.

("This and that" is offered here as a translation of "everything and nothing," which doesn't quite mean the same thing.)

Florent Moncomble said,

December 15, 2024 @ 1:00 am

French speakers don't say « ceci et cela », but they do say « ceci cela » :

« Il était au garage. Son garage. Une vieille torpédo qu'il avait. Il passait son

temps à la chouchouter et la repeindre, changer les pièces, graisser, perfectionner ceci cela dans le moteur. »

(Alphonse Boudard)

Mind you, there's no Wiktionary entry for either.

JPL said,

December 15, 2024 @ 1:42 am

"("This and that" is offered here as a translation of "everything and nothing," which doesn't quite mean the same thing.)"

Quite right, but did you mean that '"Everything and nothing"' doesn't quite mean the same thing as '"this and that"' in English, or that 'a tout et a rien' in French doesn't quite mean the same thing as what 'this and that' does in English, or that 'a tout a rien' in French doesn't quite mean the same thing as what "everything and nothing" does in English? (All true.)

I imagine that translating poetry probably does this kind of thing, looking not for lexical equivalence, but discourse equivalence of idiom. What you've got to do is to describe from a pragmatic point of view what is the equivalence in what is expressed by the two expressions in their respective discourse contexts. What is the "sentiment"? This is not a question for a flip or pat answer; it takes some thought, "describe", not "express". (Just saying "referring to 'various unspecified things'" is not enough.) For example, there is an :

"inner" logical relation common to the two, beyond the conjunction.

AntC said,

December 15, 2024 @ 2:23 am

a version of the analogous idiom existed in 4th century Latin

The Latin phrase that gave rise to the Languedoc vs Langue d'oïl opposites was 'hoc ille' . Literally 'this is it'. Which English got so overused (esp on a BBC radio satire show in the ?? 70's) as to bleach it of any meaning. If wikip is to be believed, it's since been resurrected.

Phillip Helbig said,

December 15, 2024 @ 3:51 am

Others have commented on French and Spanish (which I know less well). Never heard it in Dutch, In German, one does hear “dieses und jenes” in the same sense.

Originally, there were three demonstratives, corresponding to location: near the speaker, near the person being spoken to, far from both. Some languages (Macedonian, for example) has three corresponding definite articles. Swedish has a suffix for the definite article (like Macedonian), which is the general forrm. It also has “den här” and “den där” (or “det” instead of “den” for neuter) where the location (just two possibilities) is important. (Not sure whether colloquial English “this here” and “that there” are calques.)

In English, the three were this, that, and yon. Yon is archaic and yonder is colloquial. Obviously, dieses and jenes are cognates of this and yon. In English, the third, yon, has disappeared; in German the second, at least as far as declinable demonstrative adjectives go. For the undeclinable, the third has disappeared, leaving dies und das, like this and that.

DJL said,

December 15, 2024 @ 4:10 am

The phrase ‘esto y aquello’ is certainly common in Spanish, as in ‘sobre esto y aquello’ o ‘contra esto y aquello’ (there are at least two books by Unamuno with ‘esto y aquello’ in the title). The phrase ‘tal y tal’ means something else, as pointed out above. In Italian ‘questo e quello’ is not as common in my idiolect, but it’s the title of a well-known Spaghetti western.

Lukas Daniel Klausner said,

December 15, 2024 @ 5:40 am

In reply to Phillip, I'd say I more often hear “dies und das” in German, at least here in Austria. (But “dieses und jenes” is at least possible, even though it sounds a bit stilted and overly formal to my ears.)

Dorian Lidell said,

December 15, 2024 @ 6:06 am

Japanese has the same phrase constructed in the opposite order: あれこれ (are-kore), where "are" means "that (over there)" and "kore" means "this". The more various-sounding あれやこれや (are-ya-kore-ya) is also used, with the particle や contributing a sense of "and such"-ness.

David Morris said,

December 15, 2024 @ 6:09 am

I would suggest that 'such and such' points to one thing, while 'this and that' points to two ore even more. When my siblings and I were teenagers, we often asked our mother was was for dinner, and she'd reply either 'Wait and see' or 'This and that'. Neither of those was limited to two food items.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 15, 2024 @ 9:57 am

In Mandarin zhe4na4de 这那的 lit. "this-that" but this seems often to imply the "stuff" is pointless or tiresome. Perhaps cf. "this that and the third."

bi3ci3 彼此 lit. that (arch.)-this (arch.) is lexicalized and means 'each other, the both of us'

David Marjanović said,

December 15, 2024 @ 10:40 am

Literally "this that", or arguably "this it" at later stages.

In written German, der/die/das has indeed retreated to its function as the article. But as soon as you get slightly more colloquial, der/die/das is very much a demonstrative adjective as well, either (in the north) replacing jener/jene/jenes which has been gone from spoken language and a lot of written usage for a long time, or (in the south) replacing the entire system, leaving us with no contrast. Indeed, where exactly the limit between this and that lies in English has been difficult to learn for me.

You hear dies in Austria? I grew up without ever hearing it; it feels very northern to me.

I'd say irgendwas halt "well, something, anything" in most situations.

ulr said,

December 15, 2024 @ 5:12 pm

For me, dies und das is perfectly normal spoken standard German. And der/die/das seems to me more common in spoken German as a demonstrative pronoun (often accompanied by pointing gestures) than dieser/diese/dieses.

According to Georges' Handwörterbuch, the Latin expression was either haec et haec (citing Quintilian) or hic et (atque) ille (citing Horace). I am a bit surprised there is no citation from Cicero. (It seems the big 19th century Latin dictionaries – ultimately deriving from Forcellini's 18th century monolingual dictionary – had little interest in the language of the Christian writers of late antiquity (and the 20th century OLD ignores the Latin of late antiquity altogether).

Andrew Usher said,

December 16, 2024 @ 12:19 am

As mentioned – and as one might assume – 'this and that' (and variants) implies two or more distinct referents, a list. In contrast 'so and so' and 'such and such' do not; they may refer to one, and not necessarily one unknown, but simply better not mentioned now (also true for 'this and that', but there the reason is more likely brevity).

'So and so' can be a placeholder for both persons and things, and I'd find it more natural, while 'such and such' can only be a thing; it is also required when a modifier as in 'such-and-such a thing', where 'so and so' never occurs.

I suspect these would generally be the case for analogous expressions in other languages. I'm not currently seeing how to use the last-mentioned source but it wouldn't surpise me if the two forms in Latin were so distinguished.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

John Swindle said,

December 16, 2024 @ 4:32 am

Mandarin also has 这个那个 'this and that'. I've heard it but am not close enough to China to know how common it is.

Jaap said,

December 16, 2024 @ 5:13 am

The Dutch version is "ditjes en datjes", where the diminutives make it clear that it is about unimportant things. It means bric-a-brac when referring to physical things, and otherwise it means a trivial subject of discussion (e.g. talking about the weather).

Chas Belov said,

December 16, 2024 @ 6:38 pm

Interesting map. I see if I click on a dot, then click on the demonstrative count, I get the list of demonstratives. (As someone who tends to do less clicking, it took me a retry to discover that, so sharing for other minimal clickers.)

Just for the heck of it, I clicked all the 5-or-mores.

Maricopa, in what is now known as Arizona, has (hmm, this doesn't copy and paste well, filed a Github issue on the project):

So, from a high hill in eastern San Francisco, Mount Diablo would be sva while the Sierra foothills would be aas. ¡Nice!

Navajo has:

So, from San Francisco, Mount Diablo would be ńléí while the Sierra foothills would be ʔéidì or ʔéi, but for different reasons than for Maricopa.

Koasati has:

With the last two similar to Navajo, not sure about the distinction diffences between the two languages.

So far these have all been indigenous western hemisphere langages. The last is from an island off Africa:

Again, apparently similiar to Navajo for the last two.

I'm not sure what the difference is between distal and close. I don't know whether that represents a different shade of meaning or if it just represents that two different people analyzing the data used two different terms.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

December 18, 2024 @ 8:26 am

And, of course, in Pittsburgh we have 'n'at without the "this" part; "this" being replaced by the immediately preceding phrase, as in: "Getting ready to fry some fish next Tuesday?" / "Yeah, gotta clean out the garage 'n'at."

Note that here, 'n'at isn't surplusage — it might mean wash the fryer, make a trip to the Strip District to buy the fish, or any manner of things related to Christmas Eve fish preparation.

Although "'n'at" is more properly synonymous with "and whatnot" or "and so forth" or "et cetera", even though with some native speakers, it approaches the English verbal tic of "innit".

Chas Belov said,

December 18, 2024 @ 8:55 pm

@Benjamin E. Orsatti: Somehow in my 10+ years doing the latter part of my growing up in Pittsburgh, I never picked up "n'at" or, for that matter "redd up". I did pick up "needs washed," "yinz," "jagger bush," and "off by heart."

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

December 19, 2024 @ 8:48 am

Chas,

Is "off by heart" a localism? Yikes, I'm going to stand out like a sore thumb when we move to Syracuse this summer. And what else would you call a jagger bush? A "thorn bush", maybe? Wouldn't that also include a rose bush?

I'd venture to say that the last person to utter "redd up" unironically might have been one of Henry Clay Frick's housemaids. Same thing with "grinny" and most of the other elements on that list that keeps getting circulated around the internet.

As for "'n'at", it's definitely not within the prestige dialect, but still thrives within, say, the communities bordering the Mon and the Allegheny. I use it in informal speech, not to be "folksy", but because it does serve a useful purpose that doesn't have a precise "standard" analogue; much like "yinz" (although I've been hearing natives saying "y'all" lately, which is troubling). I fear "yinz" is becoming ossified into a "brand" — you see it now in names of coffee shops, bumper sticker footballs, etc.

Andrew Usher said,

December 19, 2024 @ 9:15 am

Is 'n'at (as you spell it) something like 'and shit' in less-regional speech? Seems like it from your quote.

I admit I could get no clue to what 'jagger bush' or 'off by heart' might mean, though again context would help.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

December 19, 2024 @ 9:36 am

Andrew,

(1) /'n'at/ ~ "and that" ~ "and shit" (but you could let "'n'at" slip at oral argument in front of a county judge, whereas "and shit" would probably earn you a trip downstairs for a drug & alcohol screening and contempt of court sanctions).

(2) You're out for a nice hike in the woods, and when you come back, your pants are all covered with these nasty, sticky, sharp, spiky seed pod things that take forever to pick out — you've walked through a jagger bush. Which is why I hesitate to substitute "thorn bush" because jaggers aren't really thorns.

(3) "Off by heart" is something that, until an hour ago, I had thought was standard Am.Eng. — it means, literally, that you can recite something without notes, or, figuratively, you know it like "the back of your hand". Anybody know what the "standard" expression for this would be?

Rodger C said,

December 19, 2024 @ 11:16 am

Anybody know what the "standard" expression for this would be?

I'd suppose "by heart" without the "off."

Philip Taylor said,

December 19, 2024 @ 1:19 pm

As a Briton, "off by heart" was immediately meaningful to me, and it is only in the light of Rodger C's immediately preceding comment that I now realise that the "off" element is (a) optional, and (b) frequently omitted. I have a feeling (and it no more than that) that one would say something like "by the age of six he had all of his [multiplication] tables off by heart" but "before the age of 11, he had learned The Song of Hiawatha by heart".

Jonathan Smith said,

December 19, 2024 @ 7:07 pm

Re: nat cf. AAVE nem, proud producer of plural pronouns derived from Mandarin men by reversithis.

Andrew Usher said,

December 20, 2024 @ 8:52 am

The immediately preceding comment seems to be irrelevant at best, and will be ignored.

Re "off by heart": I am sure Philip Taylor's observation is right. The first form, not used in standard American, would I think not work without the 'off'. Informally we could say "he had all his tables down", but there adding 'by heart' would seem redundant. It would be interesting to know if Benjamin Orsatti also has this type of distribution.

Re "jagger bush": I don't have any word for that ('thorn bush' would be understood as any shrub with thorns). The things are burrs, not thorns, and I'd say instead of "walked through a jagger bush" "got burrs (on me)". Note that 'the woods' in this sense is an idiom; I've wondered how far it extends.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

December 20, 2024 @ 10:09 am

Well, since you asked… You could certainly say "by heart" and be perfectly well understood, but it would "mark" you as being west of Wheeling, north of Butler, East of Somerset, or south of Fayette. Locally, you would either say, "He had his times tables _down_" or "He knew his times tables off by heart".

Also, a bit of internetymology reveals that "jagger bush" is apparently the source of the word "jagoff", and not the onanism I had previously thought. (https://archive.triblive.com/local/local-news/yinzers-celebrate-pittsburgh-term-jagoff-added-to-dictionary/). Who knew?! I think the consensus is that a "jagger bush", unlike a briar, bramble, thorn, etc., is simply _any_ vegetative thing that leaves annoying sharp sticky things in your clothes / flesh as you walk through it.

Philip Taylor said,

December 20, 2024 @ 12:27 pm

I am with Andrew here — for me, they are simply "burrs", and I have no special name for the plants that bear them. Glad to know that I can use "jagoff" in polite company. though !

Chas Belov said,

December 21, 2024 @ 12:38 am

@Benjamin E. Orsatti: I can't say for certain that "off by heart" is regional, but my Philadelphian father was not happy that I had picked it up and said that "by heart" was the correct version. (He might not have been happy about my picking up "needs washed" either, but I don't recall a specific conversation about that.)

I agree that "jagger bush" is a useful term and that standard English has no such comparable term.

I'll occasionally use "you all" (not "y'all") here in California but now and then a "yinz" slips out of me, either by mistake or by intent.

Andrew Usher said,

December 21, 2024 @ 1:03 am

As I recall, the origin of 'jagoff' is not known, and one newspaper article (probably with no good evidence) is not going to settle it. It might reasonably be assumed that, even if not its ultimate origin, it was at least influenced or made more popular by its connection with a term for masturbation – but the same is probably true of 'jerk', which is to an extent usable 'in polite company'.

The two-word 'you all', stress on 'all', is entirely standard, surely, in emphatic contexts.

By Philip Taylor's distribution of 'off by heart', I meant that the 'off' would be omitted after learn at least.

Philip Taylor said,

December 21, 2024 @ 3:55 am

"The two-word 'you all', stress on 'all', is entirely standard, surely, in emphatic contexts" — possibly standard in some (perhaps all) American topolects; totally non- standard in British English. If I ever need to express the concept in British English (I rarely do), I use "you (plural)".

Andrew Usher said,

December 21, 2024 @ 7:35 am

I could hardly write, or say, 'you plural' except in response to someone that had clearly mistaken me as meaning the singular; and that may be what you mean. I don't feel anyone could normally say You (plural) need to sit down, say. But an equally acceptable alternative to 'you all' is 'all of you', which may work better in your English.

Philip Taylor said,

December 21, 2024 @ 3:58 pm

I might, very occasionally, use "you (plural)" in speech, but as the parentheses indicate, I regard it as primarily a written form. An example follows : the quoted text is copied verbatim from an e-mail addressed to Victor Mair and Mark Liberman :

Andrew Usher said,

December 22, 2024 @ 8:40 am

Yes, I see. I do think I've seen that sort of use at least once. It wouldn't be natural in speech, and I don't think I'd use it that way, but I can see why someone might. The 'all' variants would of course be wrong when there are known to be exactly two, but there are still other alternatives.

By the way, I agree that quote from 'The Economist' was a blunder, though one very difficult to spot while composing!