Ambisyllabicity

« previous post | next post »

The comments on "Hypertonal conlang" (12/8/2024) include a lengthy back-and-forth about where the syllable break should be located in English words like "Cheryl". I was surprised to see that no one brought up the concept of ambisyllabicity, which has been a standard and well-accepted idea in phonology and phonetics for more than 50 years. It continues to be widely referenced in the scholarly literature — Google Scholar lists about 2,170 papers citing the term, and 260 since 2020.

The most influential source is Dan Kahn's 1976 MIT thesis, “Syllable-based Generalizations in English Phonology”. There's more to say about the 1970s' introduction into formal phonology of structures beyond phoneme strings (or distinctive feature matrices), but that's a topic for another time.

Dan's 1976 thesis introduces the concept on pp. 33-35, under the heading "Section 3 – Ambisyllabicity". You can read the whole thesis here, but for convenience, here's the text of that section:

In all traditional treatments of English syllabication, a word like atlas would consist of two syllables, [at] and [las]. Since each syllable is well-defined, it makes sense to speak of a "syllable boundary" as occurring between the [t] and [1] of atlas. This phenomenon of well-defined boundary is observed in a large class of cases in English, leading to the general assumption on the part of many phonologists that it is always possible to segment an English utterance into n well-defined syllables, i.e., to choose (n-1) intersegmental positions as syllable-boundary locations.

However, this conclusion is not a logical necessity. There need not correspond to every pair of adjacent syllables a well-defined syllable boundary. For example, as opposed to a word like atlas, where the boundary between syllables is uncontroversial, it would seem completely arbitrary to insist that hammer contains a syllable boundary either before or after the [m].

In the past this fact has been typically either ignored (but see below), in which case one arbitrarily assigns a syllable boundary in a word like hammer, or else taken as evidence that the concept of the syllable is an untenable one. The position taken here is a middle one between these two extremes: it makes sense to speak of hammer as consisting of two syllables even though there is no neat break in the segment string that will serve to define independent first and second syllables.

Using Pike's term "sonority" (each syllable contains exactly one "peak of sonority"), there appears to be a sonority trough at the [m] in hammer, as opposed to a complete break in sonority between the [t] and (1] of atlas. It would seem reasonable to maintain, then, that while hammer is bisyllabic, there is no internal syllable boundary associated with the word. As an analogy to this view of syllabic structure, one might consider mountain ranges; the claim that a given range consists of, say, five mountains loses none of its validity on the basis of one's inability to say where one mountain ends and the next begins.

The observation that polysyllabic words in English need not have well-defined syllable boundaries has in fact been made before. Careful phoneticians not committed to a theory of well-defined syllabication have suggested that intervocalic consonants in English may belong simultaneously to a preceding and a following vowel's syllable.

For example, in discussing words like being, booing, Trager & Smith (1941:233) say, "…in cases like these, the intersyllabic glide is ambisyllabic (i.e., forms phonetically the end of the first and the beginning of the second syllable), so that these words exhibit a syllabic structure exactly parallel to that of such words as bidding…"

Smalley (1968:154) points out that it is easy to identify the "crests" of syllables but notes that "it is not always possible to determine an exact syllable boundary. A consonant between two syllables may belong phonetically to both." He gives the English word money as an example of this phenomenon.

The difficulty speakers of English experience in saying, in many cases, just where one syllable ends and the next begins, referred to by Abercrombie (see quote above), is doubtless due to their uncertainty about arbitrary syllabication conventions in these ambisyllabic cases. The only phonologists who to my knowledge try to deal formally with the phenomenon of ambisyllabicity in English are Anderson & Jones (1974). For them also, words like hammer, being, booing, bidding, and money would involve ambisyllabic segments. I will have more to say about their proposals below and in Chapter II.

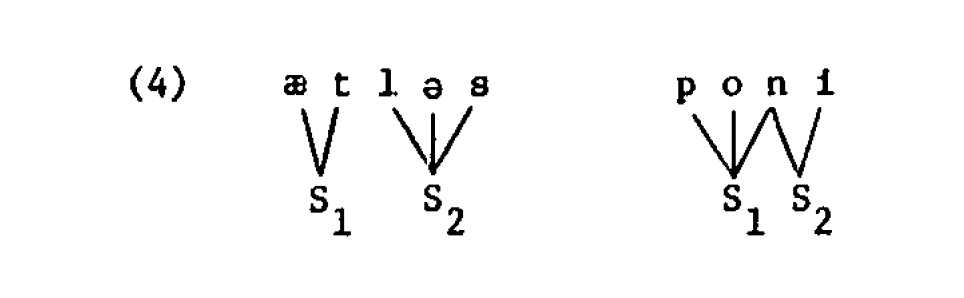

One reason that Dan's work was so effective was the notation he suggested. Here's his Figure 4, illustrating the syllable structure of atlas and pony:

His ideas was to treat syllables as "suprasegmental" or "autosegmental" entities, analogous to tones, listed on a separate tier and connected to the segmental sequence by links that obey order allow segments to be shared by two adjacent syllables.

There have been many additional ideas about syllabic (and sub-syllabic and super-syllabic) structure, the relationship of those structures to phonological features, and the place of the traditional concept of "segment" in all that. But essentially all of these proposals agree on the idea that there are some phonological entities (whether segments or features or whatever) that belong to two adjacent syllables (or syllable-like entities).

Update — the earlier works cited in the quoted section from Kahn 1976 include:

Trager & Smith, "An Outline of English Structure", 1957.

Smalley, "Manual of Articulatory Phonetics", 1963.

Anderson & Jones, "Three theses concerning phonological representations", 1974.

Chris Button said,

December 14, 2024 @ 7:16 am

I'm surprised the post does not cite the work of John Wells.

For example, his 1990 article "Syllabification and allophony" says the following:

Mark Liberman said,

December 14, 2024 @ 8:08 am

@Chris Button: "I'm surprised the post does not cite the work of John Wells."

Um, because the 1990 Wells citation (though certainly relevant) is 14 years after the clear presentation in Kahn 1976, and is one of several thousand post-1976 discussions that cite Kahn 1976?

Andrew Usher said,

December 14, 2024 @ 8:59 am

I didn't bring it up, though I believe in it, because I thought it was already being effectively granted. It was being asked which was the better syllabification, not assuming that only one could be correct. Only the number of syllables and their nuclei have any real existence, the boundaries between them are otherwise arbitrary; ambisyllabicity simply emerges from that.

In the Kahn quote, the mountain-range analogy is wrong – there's a clear definition of the boundary between mountains in that case, the low points on the ridge-line between peaks. Sonority doesn't work like that, even if you believe it's an absolute standard, the low points will be found during one sound, bot between them. Hence ambisyllabicity. But for the same reason I'd also disagree that there's one correct syllabification for 'atlas' – as the /t/ is the sonority minimum, why is it not also ambisyllabic? Why not a-tlas? Of course, we know that would be odd in English phonology and that at-las is more _useful_ in terms of a model of how English pronunciation works. So for all words, and it may and does happen that the best syllabification of the same phonetic sequence differs between languages or dialects.

In the particular case of intervocalic /r/, I gave my opinion that for Brits and others with the traditional pre-R vowel system, it is probably best to throw the R to the second always, while in General American, it's definitely better with the first vowel if that is stressed and not a diphthong.

I don't follow John Wells here, and it seems his dismissal of ambisyllabicity is just begging the question. In 'additive', if you accept ambisyllabic consonants, both intervocalic stops are, so it makes no sense to move them around as he shows. I seem to remember that his syllabifications were eccentric in maximising codas.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

Chris Button said,

December 14, 2024 @ 9:05 am

@ Mark Liberman

My point is rather that Wells makes a very effective point. Unfortunately, it's a point that makes the institution uncomfortable. The most powerful ones usually do. Lumping the point in with "several thousand" other points, really just misses the point.

Andrew Usher said,

December 14, 2024 @ 9:09 am

'The institution'? Really, do you see Wells as a rebel?

Chris Button said,

December 14, 2024 @ 9:19 am

@ Andrew Usher

Yes, like all the best academics.

He very effectively challenges the orthodoxy. Here that orthodoxy goes CV.CV.

Dick Margulis said,

December 14, 2024 @ 10:40 am

Of course, you guys are talking about syllables as sound, not syllables as written word breaks, so this is just a side note. But in written {En·glish (Merriam-Webster) | Eng·lish (American Heritage)}, the main concern of non-linguists is where to put the damn hyphen when a word breaks at the end of a line of type. And for that purpose, the conventions, even though there are two conflicting conventions, agree that doubled consonants are always* split, so it's ham·mer, which neatly resolves the ambiguity for my purposes but probably just kicks the ambiguity can down the road for yours.

* There may be exceptions I'm not thinking of.

Mark Liberman said,

December 14, 2024 @ 10:44 am

@Chris Button:

I must be missing your point. Who exactly are these orthodox CV.CV-ers? According to Wells, their position is just that CV is a "natural" or "unmarked" pattern, since it's trivially obvious that there are other phonotactic patterns. What implications this really has for e.g. the medial /r/ in "Cheryl" is not clear, though Wells feels that it implies onset-maximization. But in any case, the only "orthodox" folk that Wells cites are Fudge's 1984 work English Word Stress, which recapitulates the ideas in Fudge 1969 that were explicitly (and I think wrongly) ignored or rejected by most orthodox phonologists, and Grunwell's 1982 book "Clinical Phonology", which looks interesting but I've frankly never heard of, and is not cited by any "orthodox" phonologists whose work I've seen.

Wells 1990 argues that "not only onsets but also codas are maximized in stressed syllables", and that "ambisyllabicity is not a useful concept". That might be true, but it doesn't seem relevant to the observation that the earlier discussion failed even to note the possible existence of ambisyllabicity as a position. And I remain somewhat puzzled about which sect views onset-maximization über alles as orthodox doctrine…

Jonathan Smith said,

December 14, 2024 @ 1:35 pm

Agree "cher.yl or che.ryl" etc. is not meaningful. The mountain analogy above is good — but IMO why even bother claiming explicitly that the trough belongs simultaneously to both mountains? Just count peaks, right? On which framing my interest over there was in situations where the same "mountain gestalt" may be construed by different viewers as consisting of definitely 1!! or definitely 2!! peaks. Whereas an opposing view was that you just have to look hard enough and you'll figure out Reality.

Chris Button said,

December 14, 2024 @ 3:41 pm

@ Mark Liberman

Is John Wells' proposal mainstream/orthodox? Not as far as I'm aware

Is John Wells' proposal preferable to more mainstream/orthodox proposals? Well, it seems to me to be grounded in solid phonetic principles based on how people actually speak.

Is John Wells' proposal relevant here? Even if John Wells weren't one of the world's most eminent phoneticians, I still think his proposal merits a mention whenever ambisyllabicity rears its (superficially attractive) head

At least, that's how I see it …

Jerry Packard said,

December 14, 2024 @ 4:39 pm

It seems to me that ambisyllabicity is an eminently useful concept both substantively and theoretically; substantively because many if not most speakers would admit that, e.g., a nasal on a syllable boundary like ‘pony’ can be thought to belong phonetically to either or both sides. Theoretically because, e.g., the theoretical apparatus that allows either one tree branch or two to attach to the nasal [n] in ‘pony’ gives more explanatory possibilities than an apparatus that doesn’t. And frankly it fits more nicely with the notion that any definition of ‘syllable’ can give you an accurate syllable count, but won’t be able to tell you what phonetic stuff belongs to each syllable in a non-arbitrary way.

Yves Rehbein said,

December 14, 2024 @ 5:34 pm

I addopt Steve's approach but instead of using two syllables and 175 tones, I have to make do with one syllable and let context do the heavy lifting.

Mi mi mi. Mi mi mi, mi mi mi. Mamma mia!

[That's nonsense. Syncrony equals diachrony and ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. Not!]

Meme meemi [yours truly]

Yves Rehbein said,

December 14, 2024 @ 5:51 pm

*adopt

Which is almost on-topic. I do not either agree with the statement of "additive, morphologically /æd+ɪt+ɪv/," indeed it would be ad + dō, *dheH- as in fact, if Wiktionary is to be believed. That is is different from aditus, from adeō. But I do not see how that's relevant to Cheryl vis-a-vis churl, Carl, Carolus, Carola, Carulla (?), and I do not really understand the argument beginning "The principle of Occam’s razor". So mi mi mi it is.

Peter Cyrus said,

December 15, 2024 @ 5:49 am

Without implication for the broader question of ambisyllabicity, English seems to have lots of suffixes that begin with a vowel, and most of the examples cited involve them. I would break the syllables at the morpheme boundary: ham|er.

Andrew Usher said,

December 15, 2024 @ 11:13 pm

Yes, and that's entirely legitimate, as long as you acknowledge that it's not a matter of phonetic fact, but of preference. By the way hammer does not actually contain the suffix -er, as we can trace it, but I'm sure English speakers pronounce it just as if it did.

I'm afraid Chris Button isn't going to find anyone to agree with him, and if Wells believed that, he was likely mistaken; no one is so eminent as to never be mistaken.

Hyphenation, which has been mentioned, is to me another obsolete typographical oddity. All text prepared for the Internet is ragged-right without hyphenation; so is all handwriting as far as my experience goes. The need to fill all available space seems pretty much confined to printed newspapers, which are obsolete. And no one could argue that it is phonological, anyway.

Philip Taylor said,

December 16, 2024 @ 5:00 am

Because I am unable to write legibly at a small size, I frequently hyphenate when hand-writing greetings cards, etc. And hyphenation in print follows (at least) two quite different conventions — we Britons hyphenate on the basis of etymology, Americans hyphenate on the basis of syllabification.

As to "[a]ll text prepared for the Internet is ragged-right without hyphenation", simply not true — see (e.g.,) https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/CSS/hyphens

Chris Button said,

December 16, 2024 @ 5:36 am

Take a look at Wells' magnum opus: the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary.

Personally, I think Wells is actually hitting on something far more fundamental in terms of how syllables are built. It comes down to two concepts:

1. Sonority

2. Moraic weight

"Vowel" is a useful phonetic concept that refers to an unobstructed vocalization. It is less useful as a phonological concept, where it is simply a degree of sonority.

Take Proto-Indo-European syllables. They need a sonorant nucleus, but not necessarily a vocalic nucleus. So, /n/ [n̩] is as valid a nucleus as /j/ [i].

In some languages, a sonorant nucleus and sonorant coda can result in variable moraic weight across the syllable. A syllable like "tan" may have two forms: one with weight on "a"; one with weight on "n".

Take Old Chinese syllables. They bifurcate into what are conventionally known as "type A" and "type B" syllables on the basis of moraic weight.

Edwin Pulleyblank's writings on syllabic weight in Old Chinese seem to make the institution uncomfortable. So all manner of unconvincing proposals have been pushed out instead.

His plight sounds familiar.

Andrew Usher said,

December 16, 2024 @ 8:48 am

What is your point?

No one disagrees that non-vowels can be syllabic nuclei. No one (that knows such a language) will disagree that some languages have systems or morae not entirely coincident with syllables. Those are red herrings.

I have no idea about Pulleyblank's proposals, but ideas like that are not being suppressed. Disagreement is not suppression. Journals normally are normally quite willing (too willing, it often seems) to publish stuff by established names that contradicts the consensus. There is no suppression there. Yes, some ideas that disagree with consensus turn out to be right – we all know a few – but most don't, because the totality of scientists generally is more trustworthy than any one of them.

I don't doubt LPD uses Wells's conventions – a publisher is not likely to say no to someone like him – but that is no evidence for their correctness, as it's unlikely they were reviewed and approved for publication by anyone competent to judge. Stop thinking like a crank – science may not always be perfectly open, but it does not function by conspiracies as you are alleging and implying.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

December 16, 2024 @ 9:44 am

Philip Taylor said:

So, Shakespeare and Faulkner get the same hyphenation conventions in the Penguin editions? Although, maybe it's a slippery slope to object to that — if you're going to modify hyphenation conventions according to local speech patterns, wah nowt jus' go raht t'ah dah'lec'? And I don't think anybody wants that, in which case etymology seems like a good "neutral" metric.

But, let me ask a more basic question — why do linguists (apart from specialists parsing Homeric odes) care about how many syllables something has to begin with? Is there interesting data to be generated from an analysis of syllable counts? Is it used in historical linguistics to study language evolution or relatedness among languages, maybe? I'm not being sarcastic, I'm genuinely interested.

In other words, is there a rebuttal to the proposition put forth by esteemed linguist, K. Rogers, that, "ðɹl be time enough for counting when the dealing's done"?

Chris Button said,

December 16, 2024 @ 10:17 am

The Wellsian approach chimes with the notion that syllables may be constructed as far as phonotactic constraints allow. Then, they must break for the next syllable unless they have already broken.

When reconstructing Proto-Indo-European (PIE) or Old Chinese, the whole approach works quite well in terms of figuring out how syllables can be primordially built around ə (conventionally written as "e" in PIE) with its /a/ alternate (PIE "o").

A mistaken conflation of moras with syllables can confuse analyses though …

The relationship between moras and syllables is like the relationship between atoms and molecules.

So, moras are the building blocks of syllables in all languages–the moras are just more salient in some languages than in others.

Isn't that the point? Isn't that precisely how they became established names in the first place?

I didn't actually mean to allege or imply that at all! Admittedly it is very easy to misconstrue comments in a discussion forum like this. I think I did something similar to you earlier.

I merely meant to suggest that good ideas sometimes take a while to catch on–particularly if people have spent their careers arguing something different. I assume that's just the nature of academia?

David Marjanović said,

December 16, 2024 @ 11:11 am

Not mine! I was even taught to use = instead of – for syllable separation (as opposed to the other functions of a hyphen).

Sometimes you start a word before you notice it doesn't fit in the line. Admittedly more often in German than in English.

If it has weight on the "n", it automatically splits into two syllables, unless the "a" somehow gets reduced out of the vowel space: [tʁn̩]?.

What is the evidence that moraic weight is the difference?

(I'll take "see my forthcoming paper" for an answer.)

A long list of sound changes has indeed been found that operate on syllables; but even at a single point in time, every language yet investigated has phenomena that are most easily explained in terms of syllables. It's very uneven – many languages prioritize words, feet or morae over syllables –, but it's never zero.

Here you're talking about a pre-PIE stage, though; most likely a stage before the zero-grade developed. By PIE times, *e was distinct from the *ə found in zero-grades that couldn't be reduced to actual zero without creating consonant clusters the language treated as impossible. Example: the baby-word for "sleep" in 3sg and 3pl:

PIE: *sésti, *səsónti

Hittite: šešzi, šašanzi

**sesónti would have given **šišanzi: Hittite turned pretonic *e into i.

Philip Taylor said,

December 16, 2024 @ 11:16 am

"So, Shakespere and Faulkner get the same hyphenation conventions in the Penguin editions ?" — to be perfectly honest, I have no idea Benjamin. I became involved in the "rules" for hyphenation many years ago when Dominik Wujastyk wanted to transfer responsibility for the UK hyphenation patterns for TeX from himself and Graham Toal, and I therefore had to familiarise myself with the rules by which they were generated. The raw data were supplied by Oxford University Press, and comprised a superset of the information printed in The Oxford Minidictionary of Spelling and Word Division. That dictionary contains somewhere over 60 000 words while the data supplied by OUP contains 145954 entries. Although (as far as I can tell) the Minidictionary does not explicitly cite etymology as the over-riding criterion, it does say :

Perhaps the classic example of the difference between British and American practice is (or rather should be) "helicopter", where division by etymology would require "helico-pter" whilst division by syllabification would require "heli-cop-ter". Sadly neither the Minidictionary nor TeX with UK hyphenation patterns permit the former — the OUP database contains "helicopter[03]|heli!cop@ter".

Chas Belov said,

December 16, 2024 @ 5:21 pm

Hmm, thinking about it:

1. I think of words like Cheryl as having 1.5 syllables. I agree ambisyllabicity applies here.

2. If I'm singing "If I Had a Hammer" I split it "ha.mer". If I'm saying it in a sentence, I'm variously saying it "ham.er" or, more frequently ambisyllably (taking a guess on how to notate it) "ha,m,er".

3. Burlingame (California) is apparently (at least according to Caltrain) pronounced "bur.lin.game." But I tend to say "bur.lē,ŋ,ām" or "bur.liŋ.gām". (Sorry, not IPA fluent.)

4. "The principle of Occam’s razor, though, shows that ambisyllabicity is not a useful concept." seems intellectually lazy to me.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 16, 2024 @ 7:35 pm

"Ambisyllabicity" isn't affecting counts (i.e. Cheryl still has 2 syllables), just foregoing (in some cases) the necessity of intrasegmental boundaries. IDK if half-syllables per se have been called on analytically for English or if this is just occasional handwaviness for ambiguous-seeming cases. Cf. "sesquisyllabic", James Matisoff's term for words featuring "minor" (i.e. highly phonotactically constrained) + fuller tonic syllables, common in some Southeast Asian languages. But often these can be analyzed as cluster-onset monosyllables and scan as such in verse as pointed out by Guillaume Jacques here… so "sesquisyllabic" might also just be impressionistic, depending.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 16, 2024 @ 7:36 pm

*intersegmental

J.M.G.N said,

December 17, 2024 @ 10:13 am

@Philip Taylor

I've been trying to find the algorithms that lexicographers follow for written syllabi(fi)cation, but no luck so far.

So, for the barely three/four times a year that I need it, I trust the Random House Learner's Dictionary of American English: hel•i•cop•ter.(https://www.wordreference.com/definition/helicopter).

Chris Button said,

December 17, 2024 @ 2:04 pm

Unless, as Pulleyblank proposed, ə is epenthetic rather than the result of a reduction.

Think of it in terms of tense/lax or fortis/lenis, which can often surface as a length distinction.

Take a look at Pulleyblank's articles (most notably his 1994 "The Old Chinese origin of type A and B syllables"), and then look at how that feeds into his meticulously argued 1984 "Middle Chinese" book.

Incidentally, the 1984 book is a tour de force, but it is heavy going. I suspect that if it were less heavy going, it might have had even more of an impact on the field. It is, however, in my opinion the one book that should be essential reading for anyone interested in historical Chinese phonology.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 17, 2024 @ 6:09 pm

Pulleyblank tentatively suggested that A vs B may first have been "two types of syllables, one accented on the final [giving Type A] and one accented on the initial [giving Type B]" (1984: 179), or "two kinds of accentuation, on the second or first half of the syllable respectively" (1984: xvii), or "accent on the first mora [and] accent on the second mora" (1996: 106). That's all the details because "direct evidence by which to test this theory is difficult to find" (1984: 179). So naturally "[t]he mechanism by which [this prosodic contrast] would have given rise to the contrast in syllable types that we find in Early Middle Chinese […] remains rather obscure" (1996: 196).

As I've advised Chris, Pulleyblank's work was in fact deeply influential, not mulishly ignored, and a new publication (not a blog post) attempting to give this idea theoretical bones and render the diachronic picture less "obscure" would be welcomed. No luck thus far :D

Anyone interested in early A vs. B could first consult e.g. Schuessler (2006) ("The Qieyun system divisions as the result of vowel warping") because it leaves aside "Old Chinese" and stays closer to attested forms, meaning the reader can look at e.g. his "late Han"

B: i 死 / ie 支 / iə 思 / ɨɑ 居 / ɨo 句 / u 九

A: ei 西 / e 雞 / ə 改 / ɑ 吉 / o 勾 / ou 寳

and decide for themselves how they think such a system might have developed from earlier distinct but rhyming syllables.

Chris Button said,

December 17, 2024 @ 6:46 pm

@ Jonathan Smith

Respectfully I don't think you are properly representing Pulleyblank's position.

Neither Pulleyblank's1984 book nor 1996 article go into detail on his proposal. The 1984 book is too early and covers Middle Chinese; the 1996 article is a rebuttal of a different proposal.

His 1994 article (the one I mentioned above that you don't mention) is where he goes into real detail on the topic and provides the supporting evidence. I would recommend checking out the thoughts of Michel Ferlus in that regard too.

Regarding Pulleyblank's work, I think "deeply influential" is an understatement; it was completely transformative. His two 1962 articles shook the foundations hard.

However, he would also abandon arguments that he formerly held, and his arguments are spread across countless journal articles that are not always easy to find.

Notably, the concepts that are harder to grapple with (or more contentious) have not caught on yet. For example, distinctive vowel length for type A/B syllables (an idea that he himself proposed in 1962 and that was later adopted by others) is a far more approachable angle than distinctive moraic weight on the nucleus or coda.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 17, 2024 @ 8:07 pm

IDK about misrepresentation as I used five verbatim remarks, but true the 1994 article should be cited. No there is no "evidence" or — crucially — diachronic account there. His conclusion is that the nature of the OC contrast remains a matter of conjecture, with the remark about developments to later Chinese remaining "obscure" coming in 1996.

What there *is* in 1994 is well-argued rejection of "yod" — a point long since accepted by basically everyone. And much discussion of diphthongization including in Vietnamese, thinking which informs Schuessler (2006, 2009) and others. And re: the prosodic idea per se, there is reference to the situation in Sizang as described by Stern (1963), whose contrastive "peaking" requires heavy syllables -VV -VC -VVC.

But there are lots of other Sizang syllables types — like V and CV. Another thing that might be addressed in your upcoming paper. Again, the idea is interesting, is why. And if your remarks above represent a shift from "Pulleyblank was ignored/misunderstood" to "calling him deeply influential is just not good enough," well that is progress.

Chris Button said,

December 18, 2024 @ 11:34 am

@ Jonathan Smith

I didn't expect this topic to veer into these matters :). But I do take responsibility for bring it up!

Yes, it should be cited. You could have taken short comments on OC type-A/B prosody from any number of Pulleyblank's post-1962 publications (e.g. 1973 "word families", 1977-8 "final consonants", 2000 "morphology in OC"). But the 1994 article is the one dedicated to the matter.

Stern's article is worth reading so you can fully understand what Pulleyblank is getting at here.

One caveat is that Stern suggests contrastive syllable weight for Sizang diphthongs, which does not occur. Most likely, he was noting interference from very closely related Tedim, where the weight is applied differently from in Sizang. However, both Sizang and Tedim are internally consistent, albeit different from each other.

The influence from Tedim in Stern's materials is clear from his failure to note the secondary dissimilatory diphthongiziation of Tedim /e/ [ɛː] to Sizang /ɛa/.

Take a look at what Ferlus (2009, 2012) has written. I find his attempt to attribute the split to an actual fortis-lenis contrast in Old Chinese onsets problematic, but there is common phonological ground with Pulleyblank's proposal.

I find Schuessler's non-committal use of the word "lâche", when describing how he marks Type A syllables, to be very leading: "a symbolic circumflex accent as in French lâche 'lax'."

Which paper is that? I'm not an academic. I just wrote a PhD and then moved onto other pursuits.

I am writing a character-based etymological dictionary of Chinese and Sino-Japanese in my (limited) spare time, but that won't be ready for years unless someone decides to offer me an advance so I can work on it full time :)

Scott P. said,

December 18, 2024 @ 11:58 am

Hyphenation, which has been mentioned, is to me another obsolete typographical oddity. All text prepared for the Internet is ragged-right without hyphenation; so is all handwriting as far as my experience goes.

Adobe InDesign and other graphic design layout software packagers incorporate hyphenation as a matter of course, and it is used to create everything from packaging to web design layouts.

J.W. Brewer said,

December 18, 2024 @ 1:15 pm

The "ambisyllabic" and "sesquisyllabic" concepts can be fruitfully integrated in some but not all of the examples in the earlier thread. "Carl," for example, can be /kɑɹ.ɹl/, or maybe /kɑɹ.ɹ[ə]l/ if you resist syllabic r. On the other hand, the sequisyllabic realization of "pool" (not in my idiolect but I've certainly heard it) is /pu.əl/, without a shared phoneme spanning the light boundary. Note that while the sesquisyllables in Southeast Asian languages that originally gave rise to the label are supposedly always iambic, with the "half" or "minor" syllable coming first,* in English they are generally (maybe always, haven't put in enough thought to confirm absence of counterexamples) trochaic, with the half/minor bit at the end.

*https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minor_syllable

J.W. Brewer said,

December 18, 2024 @ 1:16 pm

Sorry, an erratum: for "first" in prior comment read "last."

J.W. Brewer said,

December 18, 2024 @ 1:16 pm

Disregard prior erratum, which was erroneous. More coffee is apparently needed.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 18, 2024 @ 6:14 pm

@Chris Button

Point re: Sizang is that we are far from a bifurcation across all or most segmental syllable types.

Re: Ferlus, no, he proposed OC-era "sesquisyllables" in Type A, an idea I sought to develop in the 2018 paper. And his resultant "tense" vs. "lax" are syllabic features, not consonant types.

And as should be obvious, most "proposals" on A vs. B amount to typographical conveniences. The phonetics are open-ended and one can find whatever connections one likes between e.g. kka vs. ka / ká vs kà / kâ vs. ka / kaa vs. ka / ka vs. kaa / etc. Except Ferlus's/mine of course

Jonathan Smith said,

December 18, 2024 @ 6:24 pm

@J.W. Brewer

This is interesting but (1) I still suspect that in SEA, "sesquisyllable" is largely descriptive as opposed to part of a theoretical apparatus concerning syllabicity specifically; and (2) I think that English mile and others simply have one syllable to most and two syllables to a (growing?) minority (many cases of which I did not appreciate until your comment in other thread + further investigations.) So for me the owl and the pussycat is just excellent iambic tetrameter while for most (?) others (including Edward Lear it would seem) it is just not, as opposed there being some middle "1.5" position.

Chris Button said,

December 18, 2024 @ 6:36 pm

That is just manifestly false. The bifurcation is precisely what makes Kuki-Chin languages (not just Sizang) particularly interesting!

Even the inadequate missionary transcriptions, which ignored tone, noted the clear bifurcation in terms of a vowel length distinction!

Yes he did. I'm struggling to understand why on you would use that to negate what I said though.

Chris Button said,

December 18, 2024 @ 7:09 pm

There are certain phonotactic constraints, which differ slightly across individual languages, but they have no bearing whatsoever on the diachronic picture.

There are also not always one-to-one matches in the two syllable types across individual languages. Sometimes that indicates a loanword; sometimes a reduction in inflectionally-derived forms (e.g. a derived verb ousts it root form); sometimes the cause is unclear.

Andrew Usher said,

December 19, 2024 @ 9:16 am

Jonathan Smith said:

> I think that English mile and others simply have one syllable to most and two syllables to a (growing?) minority …

As I've explained, this confuses production and perception. It is basically a two-syllable word to all standard speakers, but many consciously think of it as one. But that is not necessarily phonemic: if a speaker consistenly rhymes it with words like 'denial' and says that _those_ have a syllable break, then his conscious beliefs are simply incorrect and reflect neither a phonetic nor a phonemic analysis of his actual speech production.

> So for me the owl and the pussycat is just excellent iambic tetrameter while for most (?) others (including Edward Lear it would seem) it is just not, as opposed there being some middle "1.5" position.

The middle position is that these words can be scanned either way in poetry. And they can. This doesn't imply an intermediate pronunciation, but can be just as well explained by a 2-syllable 'compressible' pronunciation, as with many a and other cases where two unstressed syllables often fit into a position for one, even in the most orthodox meter.