The end of "Teaching Lucy"?

« previous post | next post »

Helen Lewis, "How one woman became the scapegoat for America's reading crisis", The Atlantic 11/13/2024:

Lucy Calkins was an education superstar. Now she’s cast as the reason a generation of students struggles to read. Can she reclaim her good name?

Until a couple of years ago, Lucy Calkins was, to many American teachers and parents, a minor deity. Thousands of U.S. schools used her curriculum, called Units of Study, to teach children to read and write. Two decades ago, her guiding principles—that children learn best when they love reading, and that teachers should try to inspire that love—became a centerpiece of the curriculum in New York City’s public schools. Her approach spread through an institute she founded at Columbia University’s Teachers College, and traveled further still via teaching materials from her publisher. Many teachers don’t refer to Units of Study by name. They simply say they are “teaching Lucy.”

But now, at the age of 72, Calkins faces the destruction of everything she has worked for. A 2020 report by a nonprofit described Units of Study as “beautifully crafted” but “unlikely to lead to literacy success for all of America’s public schoolchildren.” The criticism became impossible to ignore two years later, when the American Public Media podcast Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong accused Calkins of being one of the reasons so many American children struggle to read. (The National Assessment of Educational Progress—a test administered by the Department of Education—found in 2022 that roughly one-third of fourth and eighth graders are unable to read at the “basic” level for their age.)

The whole article is worth reading, and may help readers understand why reading instruction remains both cult-ridden and disappointingly unsuccessful.

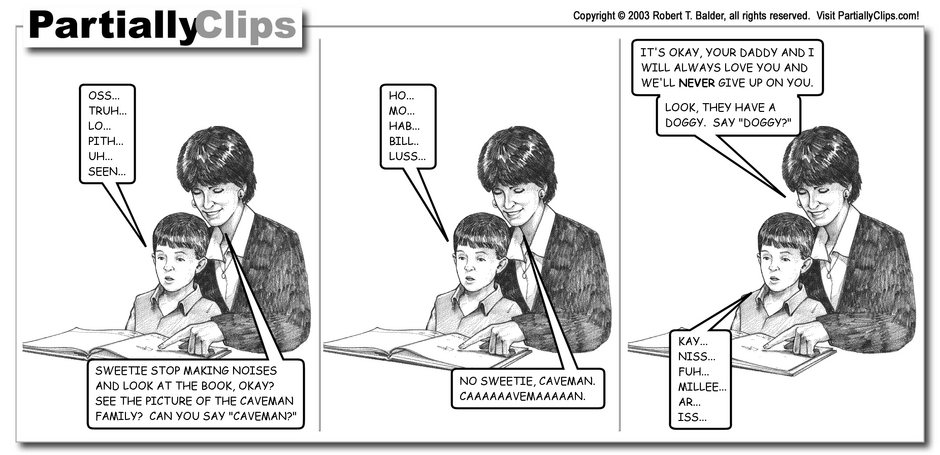

This would also be a good time to reprint this 2003 Partially Clips cartoon:

That cartoon was mainly aimed at the pre-Calkins "Whole Language" ideology, though the Atlantic article quotes several critics who characterize Calkins' system as "a strategic rebadging of whole language”.

If you're interested in a deeper dive into the current situation and trends in U.S. reading instruction, see Foster et al., "On the Same Page — A Primer on the Science of Reading and Its Future for Policymakers, School Leaders, and Advocates", Bellwether 2024:

Reading is a life-transforming and essential skill. It does not come naturally; it must be taught. Nearly all children have the capability to learn to read, with the right teaching and support. And yet, just 32% of fourth-grade students achieved reading proficiency in 2022.

If you prefer to watch and listen, the same material is available as a webinar on YouTube.

I should note that I'm a co-PI for the new Using Generative AI for Reading R&D Center, which is just being set up — so you can expect more posts on this topic as things develop.

Some relevant past posts:

"Ghoti and choughs again", 8/16/2008

"Why isn't English a Bar Mitzvah language?", 8/19/2008

"The science and politics of reading instruction", 8/17/2012

"The Gladwell Pivot", 10/28/2013

"Faimly Lfie", 6/21/2017

"Julie Washington on Dialects and Literacy", 5/21/2018

Jerry Packard said,

November 20, 2024 @ 9:40 am

In my pre-retirement role as a professor of Chinese, linguistics and Ed Psych, my colleagues, students and I were involved in reading instruction and research – Chinese kids learning Chinese in China, and undergrads learning Chinese in the US – for many years.

The two most common methods for teaching reading at the time were ‘whole language’ (i.e., sight word reading) and phonics. Over the years there has been a lot of tension between the whole language and phonics camps, as exemplified in the Partially Clips cartoon.

In my experience, I observed that most of us are naturally sight readers, while some of us have an easier time with phonics. My recollection is that most kids who had problems learning to read with whole language instruction benefitted from a greater focus on phonics. I found this to be true in learning to read Chinese (both as L1 and as L2), except that, comparatively speaking, it took longer exposure to Chinese (e.g., 3 years or more) than English for a student to effectively rely on phonics. That’s because the Chinese phonetic radicals do not reliably reflect pronunciation, especially in the high-frequency, first-encountered characters. This means that learning to read Chinese requires exposure to a lot more characters (maybe 1-2 thousand) before the phonetic regularities in the characters begin to become apparent to the learner.

I do not have a particular point to make except maybe to agree that children do learn reading best when they love reading, and that teachers should try to inspire that love by making materials available and using them often

Philip Taylor said,

November 20, 2024 @ 9:51 am

[I may have stated the following facts in a previous comment, in which case I apologise for repeating myself].

My parents (particularly my mother) taught me to read long before I started school, and she used what was then known in the U.K. as the "look-say" method, which I now believe to be the same as "whole language". I then attended a number of schools (my family moved house regularly), some of which used "look-say" while the others used phonics. I found the latter incredibly frustrating, as my mother had not only taught me to read but had also taught me the whole (English) alphabet, in both directions (ZYX and WV, UTS and RQP, ONM and LKJ, IHG, FED and CBA), so being forced to pronounce "A" as /æ/ I found complete anathema (and protested accordingly).

bks said,

November 20, 2024 @ 10:07 am

I was in charge of the "Scholastic Book Club" for my daughter's kindergarten class. There was already a bifurcation in the class of those kids who already knew the alphabet and many words, and those who did not. I attributed this to parents who had the time and inclination to stress the importance of reading to their children. I was astounded to meet parents who didn't read books at all, let alone read books to their children. (c. 1990)

J.W. Brewer said,

November 20, 2024 @ 10:25 am

It's not just reading instruction – there have been lots of transient bad-idea fads in math instruction in American K-12 schooling over the last few generations, although the unsatisfactory output of bad math instruction is easier to measure quantitatively and thus harder for the bad-idea advocates to handwave away as missing the point. Something is structurally/sociologically wrong with the schools of education faculty that makes them particularly prone to clever new ideas that end up making things worse in practice whereas e.g. the schools of engineering faculty are better at focusing on clever new ideas that may or may not work but at least accept and try to improve on what has already been shown to work rather than discard it and risk technological regression.

A related structural issue may be that lots of U.S. public school districts have some bureaucrat with a job title like Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum Development or something like that, and those bureaucrats are incentivized to push for a random and radical change in how the district teaches some subject (doesn't matter which subject) every couple of years, because anyone in that position who takes an "if it ain't broke don't fix it" approach will raise questions of whether their job and its associated salary is justified.

Philip Taylor said,

November 20, 2024 @ 10:39 am

BKS — "I attributed this to parents who had the time and inclination to stress the importance of reading to their children" — I would query "the importance" : my mother never taught me the importance of reading, she simply taught me (and encouraged me) to read for pleasure. I still treasure two of the books she and my father gave me — Coral Island (tho' I recoiled then, and still recoil to this day, at the scene in which a cat is whirled around someone's head by its tale and then thrown far out to sea …) and Tom Brown's Schooldays. Later on she became a little censorious over my choice of reading matter, and was none too impressed by my bringing home (probably from jumble sales) Roses of Martyrdom and Virtues' Household Physician. I'm fairly sure that she also confiscated the copy of Pilgrim's Progress that I had found in an "aunt's" house while visiting at around the age of eight and which I had immediately started reading (scare quotes around "aunt" because British children at that time tended to have rather more aunties and uncles than could actually claim any genetic connection). Those being pre-PC, pre-woke times, however, she had no problem with giving me a copy of The Story of Little Black Sambo which I vividly remember reading on a train at about the age of six while going to the seaside.

Philip Taylor said,

November 20, 2024 @ 12:22 pm

P.S. I was unfamiliar with "PartiallyClips" prior to this post, but having just trawled through the archive I cannot miss the opportunity to note this one — https://web.archive.org/web/20070710140545im_/http://www.partiallyclips.com/storage/dentist_lg.png

Mike Anderson said,

November 20, 2024 @ 1:27 pm

"… reading instruction remains both cult-ridden and disappointingly unsuccessful."

And yet, many of us (everyone reading this blog) learned to read quite well. How'd that happen? (FYI, Dad started me off with comic books and the backs of cereal boxes.)

STW said,

November 20, 2024 @ 2:42 pm

My daughter received her PhD in reading education. She had earlier despaired, as a classroom teacher, trying to help 7th graders who struggled to read. I asked her about "Told a Story" after I had listened to it. She figuratively nodded her head (by telephone) and said she'd learned all about that as part of her studies. Apparently many at the top of the reading education food chain knew the problems but could not overcome marketing and the true believers.

As parents we noticed a marked difference in her reading with phonics and that of her sister who came along in time for whole language.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

November 20, 2024 @ 2:47 pm

Having read the whole article, I found it was surprisingly nuanced given the limitations of its length. The author does touch on the complexities and costs of U.S. public school districts’ curricula decision-making.

I thought the key revelation about Lucy Calkins came in this quote from her, much further down in the story: “I felt like phonics was something that you have the phonics experts teach.” Unfortunately, the writer of the article apparently did not ask about whether Calkins had training in phonics or other areas of linguistics.

My conclusion is that Calkins is enthusiastic about sharing her love of what I would call “reading for understanding,” but Calkins herself has little enthusiasm for understanding language, even though language is foundational to reading. I think her work would have been strengthened if she had sought more collaboration with linguistics experts — including but not limited to phonics experts. Calkins does not seem to recognize her own blind spots.

Rick Rubenstein said,

November 20, 2024 @ 5:11 pm

I think the main problem with any of these teaching methods is that reading is simply too difficult a skill to expect to learn primarily in school. I'd bet a fair sum that a child's reading level correlates weakly with what teaching method they received in school, and extremely strongly with the literacy level of their parents (which in turn of course correlates strongly with the wealth of said parents).

KeithB said,

November 20, 2024 @ 5:40 pm

My wife -a Preschool Teacher – creates "Book Buddies", a book and associated soft toy in a bag. She sent them home with her students and expected the parents to read it to their children. The children are excited to get them, and hopefully pester their parents to read to them.

J.W. Brewer said,

November 20, 2024 @ 5:52 pm

How much parents encourage reading in the house and/or model it by their own behavior is obviously an important factor, but there are plenty of historical examples of societies transitioning from low literacy rates to high literacy rates in fairly short timeframes, and during those transitions it is perfectly commonplace for there to be literate children of illiterate parents. Which means that Rick Rubenstein's bet is likely too pessimistic to account for phenomena like that.

More substantively, one difficulty is that the pedagogy that may be most effective in promoting further development of reading skills for the students who are already successfully picking up reading in their home environment may be dramatically different from the pedagogy that successfully inculcates the basics for the students who are not getting any "instruction" or encouragement in reading, whether formal or informal, in their home environment. Some schools may due to the nature of the community they serve have students overwhelmingly of one sort or the other (and of course it's a spectrum rather than a binary division), but many schools will have quite a mix of students as to this factor, meaning that a one-size-fits-all approach is highly suboptimal yet many classroom environments are not well suited for much beyond a one-size-fits-all approach.

Philip Taylor said,

November 21, 2024 @ 3:58 am

Rick — "I'd bet a fair sum that a child's reading level correlates […] strongly with the literacy level of their parents (which in turn of course correlates strongly with the wealth of said parents)." I respectfully beg to differ with the last part. Both of my parents were literate (and their library included works such as German with tears and Poems of Today) but not only was neither wealthy, they were borderline penurious. My father droves London 'buses and cleaned windows, my mother worked in a typewriter-ribbon factory. Yet despite their poverty I was graded "three years ahead of class" in reading skills.

David Morris said,

November 21, 2024 @ 6:07 am

There are some students learning maths who easily understand mathematical symbols and others who do better on 'someone bought x items for y amount each. how much did they pay and how much change do they have'-type questions. Some music students easily understand music notation and can sight read, and other play by ear and improvise. There are probably similar options for all subjects.

I have no doubt that some students respond better to whole-language/reading (by whatever name) and others to phonics/structured instructions. Given a choice between either/or and both/and, I will take both/and every time.

Philip Taylor said,

November 21, 2024 @ 6:42 am

Mike Anderson — "Dad started me off with comic books and the backs of cereal boxes" — I don't think either of my parents specifically encouraged me to read product packaging, but my introduction to the French language was at the age of nine when I taught myself to read the French on the back of H.P. Sauce bottles — Cette sauce de haute qualité est un mélange de fruits orientaux, d’épices et de vinaigre. Elle est absolument pur et ne contient aucune matiere colouratif ni preservatif.. The opening words remain with me to this day, but sadly I can no longer recall how it ended.

Roly H said,

November 21, 2024 @ 8:14 am

I can remember being part of a chorus of tots in Miss King's PNEU school chanting "A says æ, B says b etc…" in the England of the 1940's. But I also grew up in a household surrounded by books and with the TLS delivered weekly. Two close relatives, my grandfather and my uncle, were published writers and my grandfather read me a bed-time storey every night. I remember these started with the likes of Beatrix Potter (and little Black Sambo!) through A.A. Milne, Hugh Lofting's "Dr Doolittle" books, "Treasure Island" and Arthur Ransome's "Swallows and Amazons" books all the way to Dickens, with countless others in between. My grandfather had a knack of ending his nightly stories at a cliff hanger moment, encouraging me to read on. This nightly ritual continued long after I was able to read perfectly well by myself.

It was only later that I discovered that books were not an integral part of everyone's family.

So count me among those who believe that the home attitude to books and reading will have the major influence on the young. (And I still have all the Swallows and Amazons books!)

Jerry Packard said,

November 21, 2024 @ 11:02 am

In our research on children learning to read in China, one of our manipulated variables was ‘volume of reading’ (VOR). The VOR group manipulation included reading materials placed in a box at the front of each row, with children encouraged to read those materials during ‘down’ time (recess, rest times, etc.), and also encouraged to take those materials home to read with parents.

One salient observation we made was that the culture of ‘reading at home with parents’ was virtually non-existent in China, unlike in the US where it is common. For details, see: Li, W., Gaffney, J. S., Packard, J. L. (Eds.) (2002). _Chinese Children’s Reading Acquisition: Theoretical and Pedagogical Issues_. Dordrecht, Holland: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 266 pages

Kate Bunting said,

November 21, 2024 @ 11:24 am

I had pretty much the same experience as Philip Taylor. I remember the appearance of whole words, so (most) spelling errors are glaringly obvious to me. My mother told me that one of my primary school teachers reported that, when the class were being taught 'bat, bit, but' and so on I declared "This is silly"!

Rodger C said,

November 21, 2024 @ 11:58 am

correlates weakly with what teaching method they received in school, and extremely strongly with the literacy level of their parents (which in turn of course correlates strongly with the wealth of said parents).

My father was a welder, my mother a homemaker. She read murder mysteries; he read technical literature and "men's" magazines. When I was little, every Disney comic included a page-long print story. My mother would read me this story while I sat on the chair arm looking at the page. One day (as she later told the story) I corrected her reading. "Well, then why don't you read me the rest of the story?" So I did. I was three. I literally don't remember a time when I couldn't read.

First grade: I could already read everything , and as soon as I learned to make letters for myself I passed a note to my teacher: "Gee, things sure are boring around here!" Soon I was in second grade. Spent the rest of my school years, up to first semester of MA, two years younger than everybody around me.

Julian said,

November 21, 2024 @ 4:41 pm

I suspect that readers of this blog, recalling their childhood learning experiences, are not very representative of the median child.

Julian said,

November 21, 2024 @ 4:45 pm

I intended the above comment to add the following, but the system stripped it off because presumably because I put carets around it, so I'll put brackets around it here:

(Insert smiley you know the one with the bracket and colon but I can never remember which order they go in does that make me left hemisphere or right hemisphere)

Speedwell said,

November 21, 2024 @ 7:40 pm

I'm autistic and didn't speak out loud until I was four (I could actually speak, but refused until I could sound like standard adult speakers to my own satisfaction). Nevertheless my mother insisted I learned to read before I was two and a half, through a combination of Sesame Street and being read to. One night she was tired and she tried to skip over words in a new book I'd recently been given. Every time she did I would fidget and fuss. Finally she said, "if you can't sit still, there will be no reading". I picked the book up and turned back to the beginning and started reading it (silently). Mom figured out something was up and started asking me to point to certain words on the page, which I was able to do. Then I did something that blew her mind. I pointed to "I" and "can" and "read". The subsequent flurry of excitement from my parents was scary and I thought I had done something wrong, so I refused to "perform" for the education specialist they took me to, haha. It took a beloved babysitter to finally confirm I was actually reading.

Josh R. said,

November 21, 2024 @ 8:27 pm

I'm with Julian on this. I also think this is where the whole whole language/balanced literacy/Lucy Calkins movement went wrong. They confused result with process. They looked at how good readers dealt with a text, and tried to teach that, which worked for the 40% of students that take well to reading in any case, but which was not so helpful for the other 60%.

Jenny Chu said,

November 22, 2024 @ 12:23 am

I don't remember learning to read; I do remember being surprised to learn, in kindergarten, that there were other children who didn't yet know how to read.

My children, on the other hand, definitively learned to read from early exposure to Starfall, a wonderful phonics website perfectly designed to captivate toddlers and preschoolers. I think they started going on Starfall at about two and a half, and were both comfortably reading Cat in the Hat type of books by the age of three. Yes, we have lots of books in the house; yes, we have read to the kids since they were babies; but it was Starfall that really taught them how.

Some years later (I think my kids were reading David Eddings and Rick Riordan), a friend and her six-year-old visited from Canada. The little girl was eager and interested in reading, but had little sense of how to sound out words. As we read Cat in the Hat together, she would read a word aloud when she recognized it, but if she didn't know a word, that was it – she just looked up at me and said, "What's this word?" I wondered if that difficulty was a result of the Lucy method.

Peter Grubtal said,

November 22, 2024 @ 4:38 am

J. W. Brewer

There was an old cynical adage:

Those who can, do, those who can't, teach, and those who can't teach, teach teachers.

Laura Morland said,

November 22, 2024 @ 6:19 am

Chiming in here as another reader of this blog who is not at all representative of the median child. (cf. Julian above)

Clearly a large percentage of children needs to be taught phonics. But some of us are self-taught, early readers who invented the "whole language" approach all by ourselves. In my case, repetition helped: my mother grew tired of reading _The Cat in the Hat_ (indeed) out loud, and so she recorded it for me, on a reel-to-reel tape recorder. I can still remember being three years old, sitting cross-legged in my bedroom next to this large machine, staring at the book while listening to the words… and then suddenly one day all the words on the page had meaning, and I didn't need the tape recorder anymore. (It wasn't memorization; I could read anything from that point on.)

Despite going to a "nursery school" (as they were called then) populated in large part by other children of college professors, it would be another three years before I knew anyone else my age who was able to read. Not until I reached the first grade, and had to sit through phonics lessons that I neither wanted nor needed. (By then, I'd learned to hide my skill, because it made me unpopular.)

Like Kate Bunting, spelling errors have always been glaringly obvious to me, And like Kate, being an early reader led to problems in school. I detested the "reading circle," because I would rather read by myself. (And for the record, my parents never read a single book to me after I mastered Dr. Seuss. Reading was my solitary pleasure.)

Intriguing fact: the downside of being a visual learner is that I am not able to learn (i.e., remember) a new word, in any language, unless I can see it written down first. My godson is extremely dyslexic, and yet had mastered a wide-ranging vocabulary before finally learning to read at age 16. I'm completely baffled by how he is able to store words in his brain without knowing the written equivalent. Another downside: being visually-dependent is a hindrance to properly pronouncing words in languages other than English, for obvious reasons.

Laura Morland said,

November 22, 2024 @ 6:30 am

Postscript: As might be obvious from my previous comment, I completely disagree with the statement by Foster, et al.:

"Reading… does not come naturally; it must be taught."

As Speedwell writes above, he learned to read by himself (although Sesame Street was involved) at age two, and I did as well, at age three. I was given no instruction; simply the same couple of books were read to me, over and over.

Foster and colleagues clearly need a larger data pool.

David Marjanović said,

November 22, 2024 @ 7:33 am

Another one here: knew all the letters (and all the traffic signs and more) by age 4, figured out how to read by gazing at an envelope on the floor, entered kindergarten (unusually late) at age 5, read everything they had there. Unlike in the US it's normal to arrive in school at age 6 completely illiterate except maybe for one's name in all-caps.

Where I come from, this happens at the federal level. The job and salary of the minister of education are not questioned (unlike in the US), but nonetheless every new minister feels the urge to justify their existence by changing something, and so on all the way down.

That's a very common problem with teaching reading as if it's Chinese. My brother kept stumbling over unknown words for at least 20 years – and that's in German, where just reading one letter after another will get you a lot farther than in English. I was spared the reading-as-vocabulary method simply because I'm 3 years older.

Jerry Packard said,

November 22, 2024 @ 7:51 am

I completely disagree with the statement by Foster, et al.:

"Reading… does not come naturally; it must be taught."

We can do a thought experiment here. A bunch of pre-literate pre-lingual infants stranded somehow on an isolated island would presumably develop some sort of spoken language (?) as they developed into adulthood. If you accept that now imagine that there are scores of books of every sort scattered about – picture books, Cat in the Hat, readers, dictionaries etc. I cannot imagine in this poor group of souls that reading would spontaneously arise, even over several generations.

Why? Because we humans are hard-wired to acquire spoken language and not reading. [disclaimer: do not try this at home].

Andrew Usher said,

November 22, 2024 @ 8:25 am

Nor do I remember learning to read, no more than I do learning to speak. But it is conceded that our standard methods of education need to be targeted at average children, not especially gifted ones; the latter will learn no matter what.

Education is inherently empirical: no one, no matter how smart, sensitive, etc., can devise a technique from scratch. What has and hasn't worked in the past if what we _must_ go on; scientific research can help, but results are still the final test. No doubt much of the time that scientific input is ignored is because of the reality or perception that it's trying to ignore what really happens in practice.

Formal education can only take one so far; while true in all fields, in reading the 'so far' is (or should be) reached especially early. Once basic competence has been reached the only way to get much better in practical terms is to read a lot, and it doesn't much matter what, as long as it's text and not specifically written for learning children. The Internet should provide an unlimited source of reading material, on practically any subject one might have interest in; if I'd had the modern-day Internet, instead of books, I'm sure I'd have reached my current level at least as well and at least as fast. That is simply the one thing everyone having notable proficiency will tell you: they read (past or present) a lot.

Perhaps the most important point to stress is related to this:

(J.W.Brewer)

> … lots of U.S. public school districts have some bureaucrat with a job title like Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum Development or something like that, and those bureaucrats are incentivized to push for a random and radical change in how the district teaches some subject (doesn't matter which subject) every couple of years …

Of course. And when anything goes worse in the US than in other countries, one can generally assume stupid bureaucracy is the reason. But surely the holder of such an office isn't himself responsible, right? The system encourages doing this, and even allowing such large changes to be made at the school-district level is bizarre. Such a position may be justified, but would do far more good making smaller changes to a wide variety of subjects than a large change to one. Whom do they need to impress by doing the latter, or is it just a matter of ego? DM's independent response suggests the 'ego' option, but it shows a systemic problem either way.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

John Swindle said,

November 22, 2024 @ 7:43 pm

In mid-century mid-America kindergartners (age 5) weren't supposed to learn to read. I think they wanted us to become socialized or something first. I only knew how to read short environmental words in all caps, like "FORD," "HOT," "COLD, "OFF," "ON," and my own given name, which I didn't necessarily spell right. Fortunately, in a way, I had to spend a month in the hospital about then. Sister Mary Rose, if I remember her name correctly, who was also smuggling extra milk to me, took pity on me and taught me to read. I have registered and respect the widespread dislike for Roman Catholic nuns, especially among those who've attended Catholic schools, but my own experience of Catholic nuns as a Protestant child was quite different.

Philip Taylor said,

November 23, 2024 @ 5:13 am

"Hot", "cold", "off" and "on" I can all see as words that a child in the environment that you describe might well encounter, but I am intrigued to know in what context you encountered "ford". Was there a nearby stream that could be safely crossed at only one point ?

Andrew Usher said,

November 23, 2024 @ 8:52 am

The automobile? Surely that's the default meaning of 'ford', or rather 'Ford', to Americans, and one could read it from the vehicles. The riverine meaning is practically historical for me, in modern use it's wade/ride/drive across.

Philip Taylor said,

November 23, 2024 @ 9:59 am

But John writes of "environmental" words, Andrew. Would a word found on a car qualify as an "environmental" word ?

Rodger C said,

November 23, 2024 @ 11:37 am

If there were cars in his environment, as there must have been.

Rodger C said,

November 23, 2024 @ 11:40 am

Unlike in the US it's normal to arrive in school at age 6 completely illiterate except maybe for one's name in all-caps.

This was normal in the US day; it's why everybody was so amazed at me. By the way, spending one's schooling two years younger than one's classmates isn't something I recommend.

Rodger C said,

November 24, 2024 @ 11:14 am

*in the US in my day

Andreas Johansson said,

November 25, 2024 @ 5:06 am

While I wasn't as dyslectic as Laura Moreland's godson, in my early school years I did combine distinctly subpar reading and writing skills with a vocabulary well beyond that expected for my age.

I arrived at school at age seven (the normal age in Sweden) knowing the alphabet and able to write my name, but without having grokked that the sequence of letters used to write a word had something to do with how you pronounce it, so I worried about how one was ever going to be able to memorize the spellings of thousands of words. Learning that there were rules for spelling was a revelation, but not one that allowed me to learn quickly or efficiently.

When I finally, around age ten, had reached the point that I could read for pleasure, though, learning sped up and I finished primary school with above-average reading and writing grades.