The evolving PubMed landscape

« previous post | next post »

Following up on "Are LLMs writing PubMed articles?", 7/7/2024, Cervantes suggested a factor, besides LLM availability, that has been influencing the distribution of word frequencies in PubMed's index:

As an investigator whose own papers are indexed in PubMed, and who has been watching the trends in scientific fashion for some decades, I can come up with other explanations. For one thing, it's easier to get exploratory and qualitative research published nowadays than it once was. Reviewers and editors are less inclined to insist that only hypothesis driven research is worthy of their journal — and, with open access, there are a lot more journals, including some with low standards and others that do insist on decent quality but will accept a wide range of papers. It's even possible now to publish protocols for work that hasn't been done yet. So it doesn't surprise me at all that words like "explore" and "delve" (which is a near synonym, BTW) are more likely to show up in abstracts, because that's more likely to be what the paper is doing.

I agree, although it remains unclear whether those changes have been strong enough to explain the effects documented in Dmitry Kobak et al., "Delving into ChatGPT usage in academic writing through excess vocabulary", arXiv.org 7/3/2024.

I'll add another factor related to Cervantes' comment, namely the changing distribution of PubMed's cited sources.

Looking over the list of sources for [delve] in PubMed, I saw quite a few whose representation in PubMed has been increasing rapidly. The table below lists the per-100k citation numbers by year for the first four that I looked into, along with their proportions of increase between 2022 and 2024:

| StatPearls | Heliyon | medRxiv | arXiv | |

| 2019 | 0 | 44.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2020 | 0 | 139.1 | 45.8 | 2.9 |

| 2021 | 0 | 169.3 | 35.6 | 3.0 |

| 2022 | 54.0 | 227.9 | 18.8 | 1.3 |

| 2023 | 421.2 | 671.3 | 115.1 | 28.1 |

| 2024 | 1004.2 | 1005.3 | 133.3 | 39.3 |

| 2024/2022 | 18.6 | 4.4 | 7.1 | 30.2 |

At least in the case of arXiv, this is because PubMed is paying more attention — but in any case, those proportional changes are as large or larger than the ones that Kobak et al. used to argue for the role of LLMs. This doesn't mean that Kobak et al. are wrong, just that there are other things going on that should be taken into account.

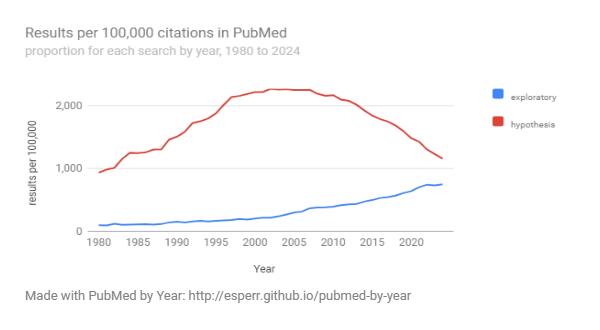

Update — additional support for Cervantes' observation can be found in a comparison of counts for [exploratory] vs. [hypothesis] over the decades since John Tukey introduced "Exploratory Data Analysis" as an alternative to "hypothesis testing" (see here for a recent summary):

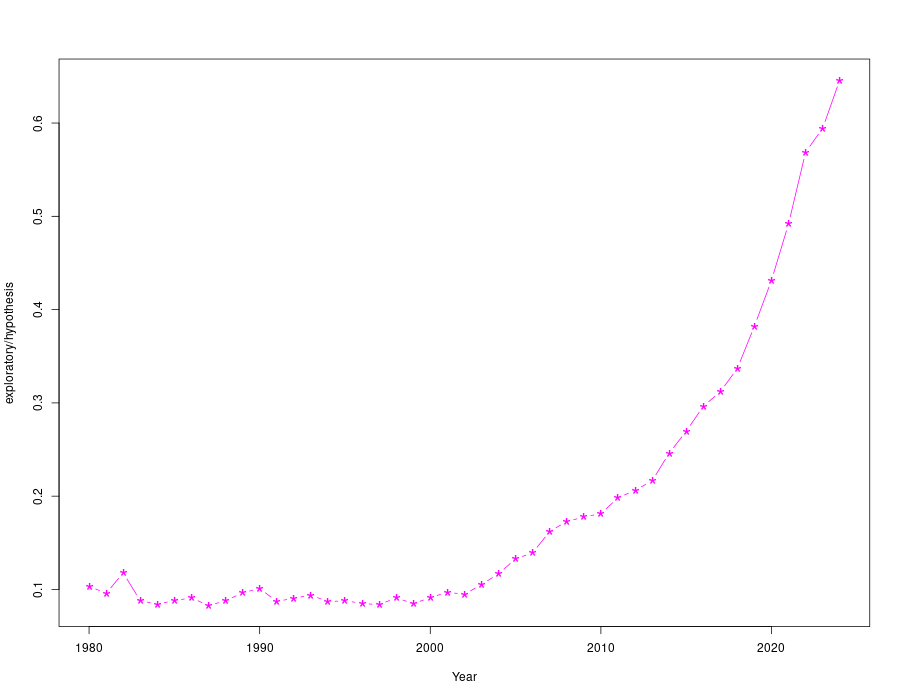

Plotting the ratio:

Cervantes said,

July 9, 2024 @ 11:43 am

Yes, that's pretty much what I meant. I really don't see any reason to attribute this to LLMs — why would they prefer explor* more than humans? But there's at least a highly plausible argument that this has to do with real trends in the scientific enterprise.

David Marjanović said,

July 9, 2024 @ 1:23 pm

Delve, however, is not a word I'm used to seeing in scientific papers, and LLMs are independently known to use it a lot.

Cervantes said,

July 9, 2024 @ 1:58 pm

If you read Mark's original post, you'll note that the actual frequency of delve remains quite low. There was a large percentage increase but the number is still small. I can certainly see someone writing an abstract with "we delve into the question/problem . . . .," but explore remains far more frequent.