Are LLMs writing PubMed articles?

« previous post | next post »

Kyle Orland, "The telltale words that could identify generative AI text", ars technica 7/1/2024

In a pre-print paper posted earlier this month, four researchers from Germany's University of Tubingen and Northwestern University said they were inspired by studies that measured the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by looking at excess deaths compared to the recent past. By taking a similar look at "excess word usage" after LLM writing tools became widely available in late 2022, the researchers found that "the appearance of LLMs led to an abrupt increase in the frequency of certain style words" that was "unprecedented in both quality and quantity."

To measure these vocabulary changes, the researchers analyzed 14 million paper abstracts published on PubMed between 2010 and 2024, tracking the relative frequency of each word as it appeared across each year. They then compared the expected frequency of those words (based on the pre-2023 trendline) to the actual frequency of those words in abstracts from 2023 and 2024, when LLMs were in widespread use.

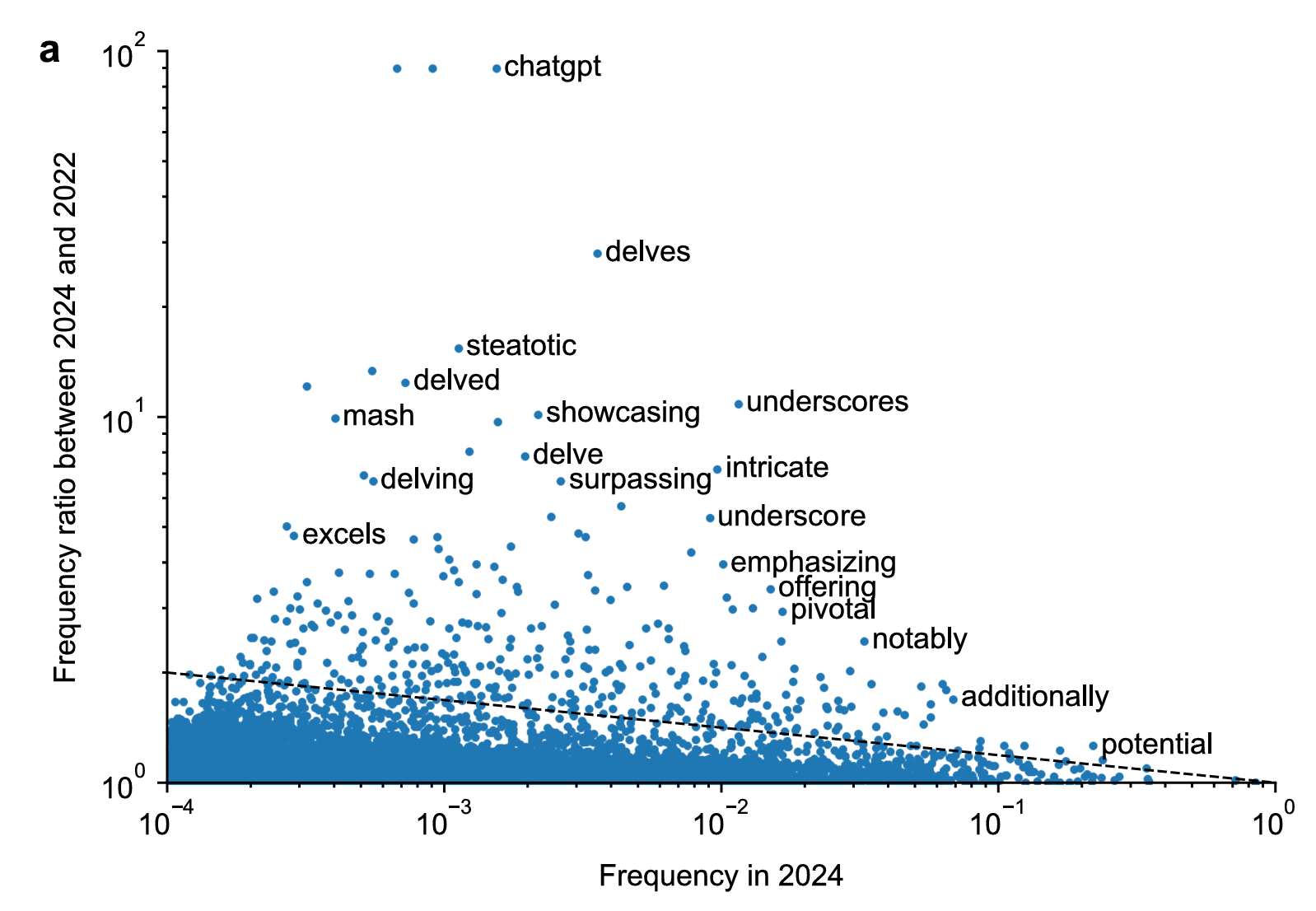

The results found a number of words that were extremely uncommon in these scientific abstracts before 2023 that suddenly surged in popularity after LLMs were introduced. The word "delves," for instance, shows up in 25 times as many 2024 papers as the pre-LLM trend would expect; words like "showcasing" and "underscores" increased in usage by nine times as well. Other previously common words became notably more common in post-LLM abstracts: the frequency of "potential" increased 4.1 percentage points; "findings" by 2.7 percentage points; and "crucial" by 2.6 percentage points, for instance.

The cited paper is Dmitry Kobak et al., "Delving into ChatGPT usage in academic writing through excess vocabulary", arXiv.org 7/3/2024 (v.1 6/11/2024):

Recent large language models (LLMs) can generate and revise text with human-level performance, and have been widely commercialized in systems like ChatGPT. These models come with clear limitations: they can produce inaccurate information, reinforce existing biases, and be easily misused. Yet, many scientists have been using them to assist their scholarly writing. How wide-spread is LLM usage in the academic literature currently? To answer this question, we use an unbiased, large-scale approach, free from any assumptions on academic LLM usage. We study vocabulary changes in 14 million PubMed abstracts from 2010-2024, and show how the appearance of LLMs led to an abrupt increase in the frequency of certain style words. Our analysis based on excess words usage suggests that at least 10% of 2024 abstracts were processed with LLMs. This lower bound differed across disciplines, countries, and journals, and was as high as 30% for some PubMed sub-corpora. We show that the appearance of LLM-based writing assistants has had an unprecedented impact in the scientific literature, surpassing the effect of major world events such as the Covid pandemic.

This claim may very well be right — I haven't evaluated their statistical model, in which what counts as "excess word usage" will very much depend on the assumed nature of the underlying stochastic processes — but there are some things about the argument that leave me skeptical.

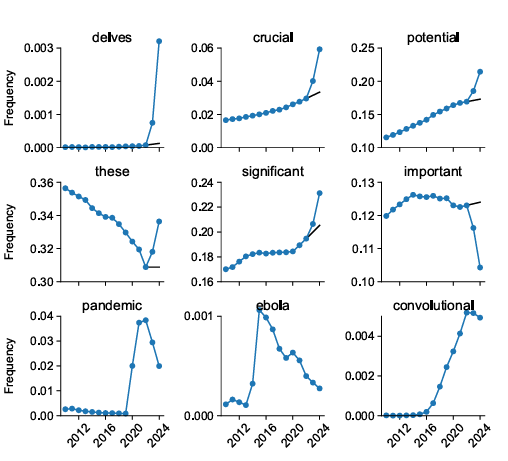

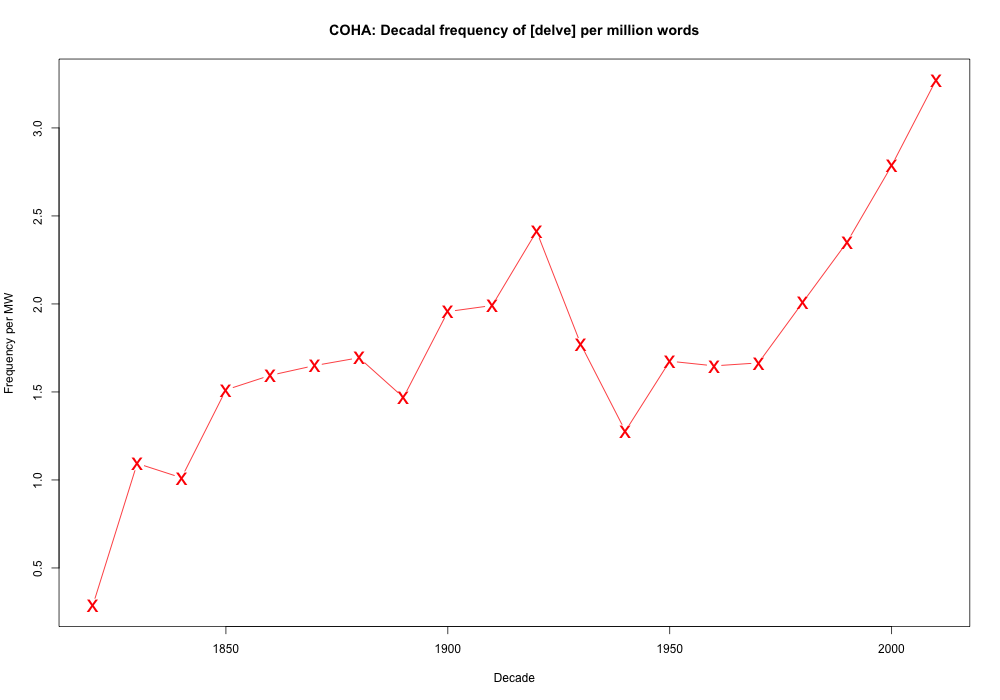

The first thing to note is that some of the cited increases are much more "abrupt" than others, with forms of the verb delve leading the list, as shown in their Figure 1:

And their Figure 2(a), captioned "Frequencies in 2024 and frequency ratios (r). Both axes are on log-scale":

(I believe that the paper's authors downloaded the PubMed data and did their own searches and counts, but if you do your own exploration on the PubMed site, keep in mind that PubMed apparently searches by lemma, so that a search for "delves" also hits on "delve", "delving", "delved" — which I'll signal in the usual way with square brackets, e.g. [delve]. And PubMed returns the number of citations (abstracts or available texts) per year containing the lemmas in question — for the relative frequency results, normalizing for the number of available citations per year, you can use Ed Sperr's github page. I haven't tried to separate the alternative forms, but that should not matter for the points I'm making below.)

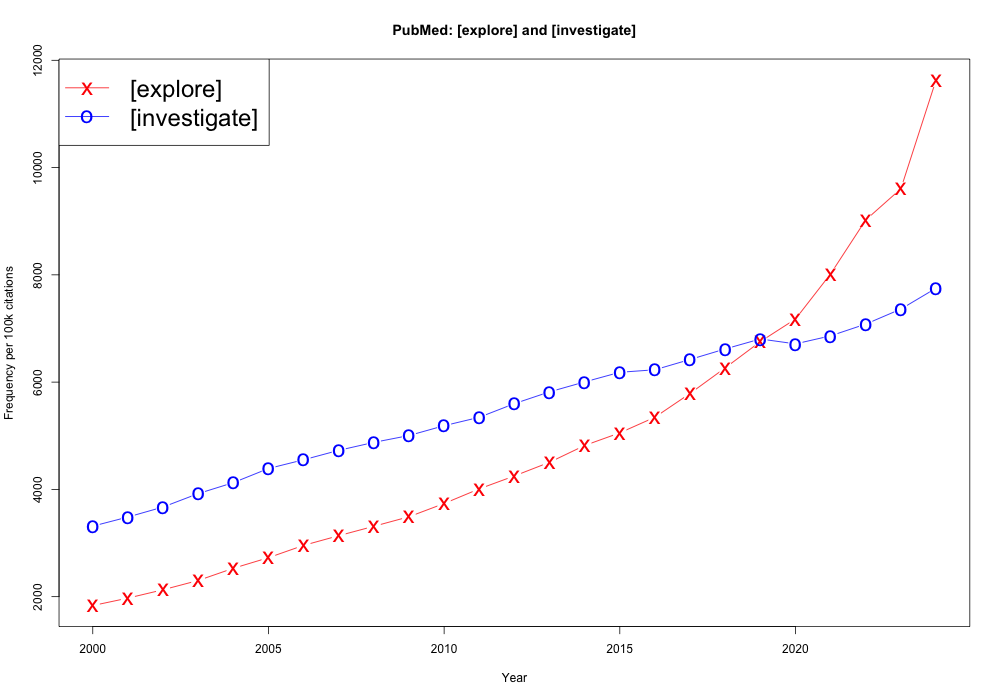

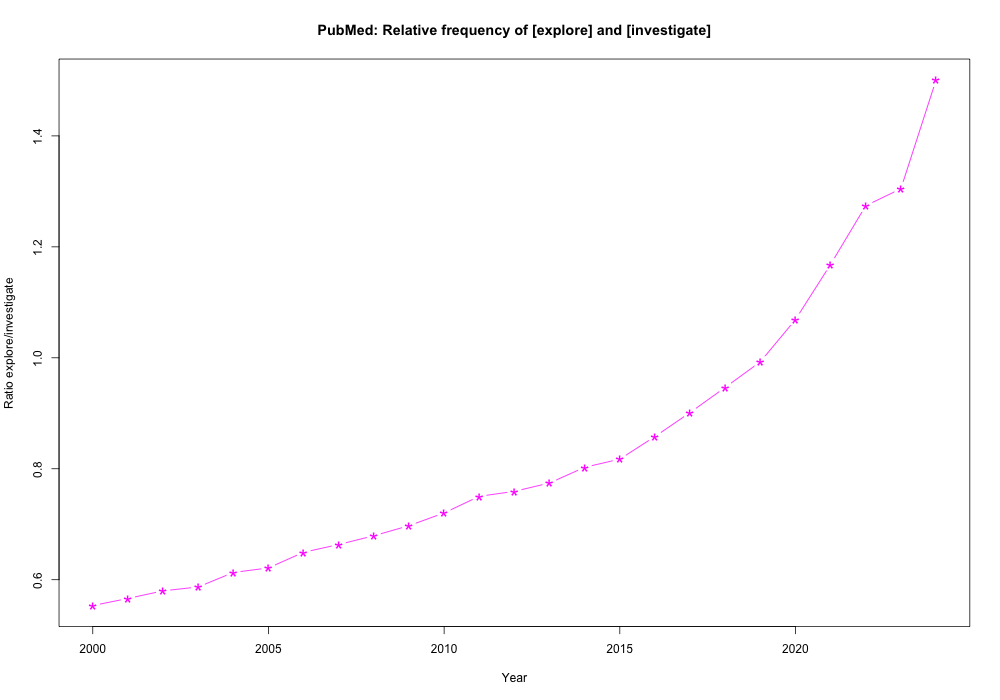

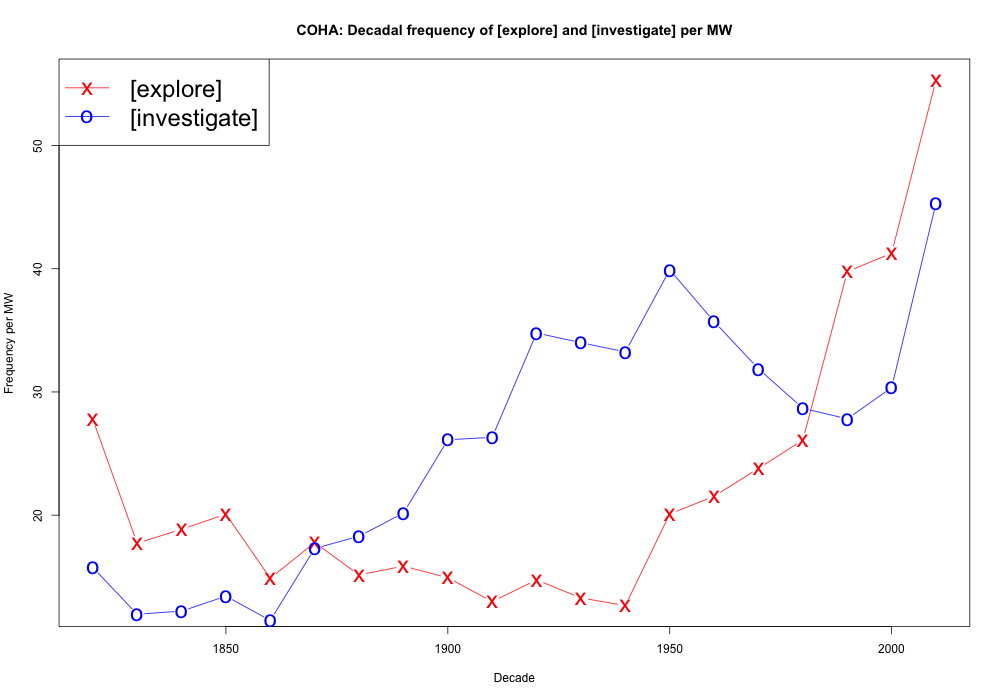

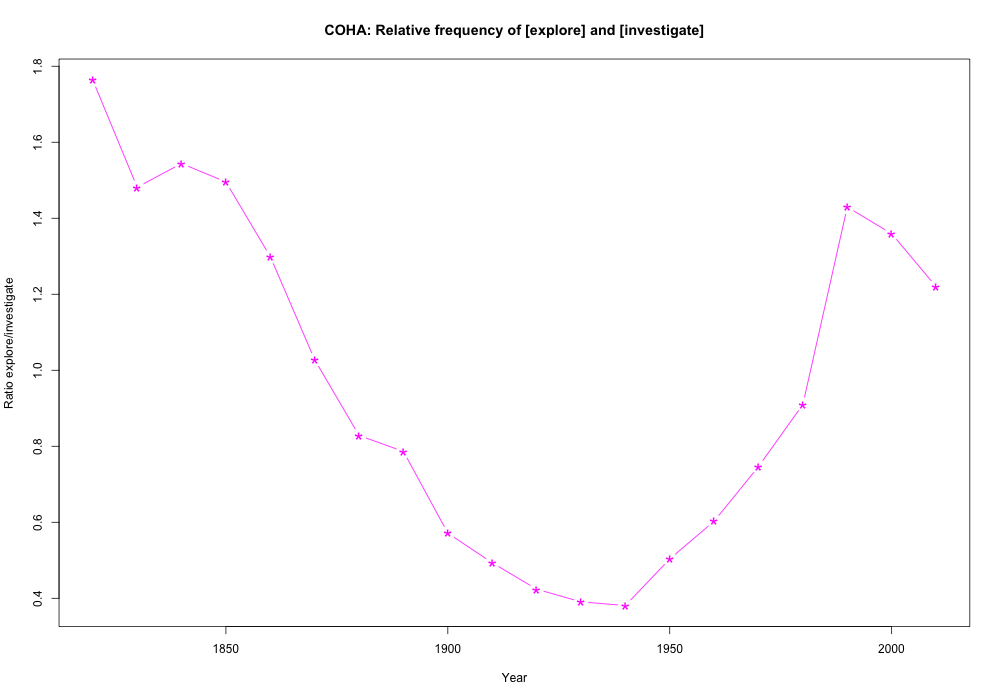

My first observation is that decades-long trends in relative PubMed word usage are common, and not just because of real-world references like ebola, covid, and chatgpt. For example, [explore] has been gaining on [investigate] for 25 years or so, with acceleration over the past decade:

It's also worth noting that trends of similar size (and often similar direction) can be found in more general sources than PubMed, e.g. Corpus of Historical American English:

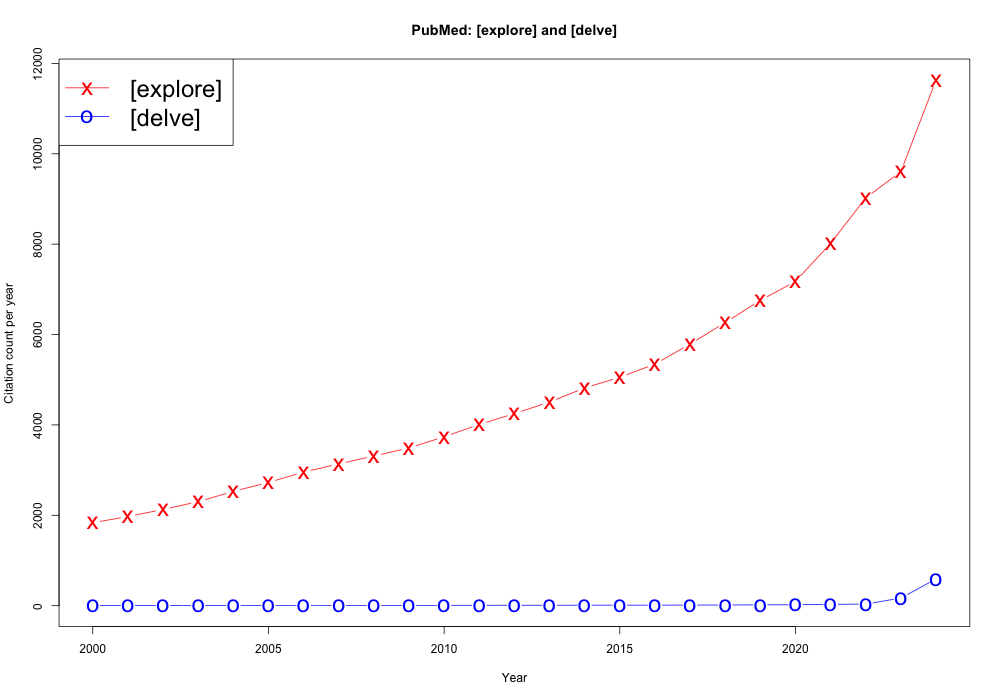

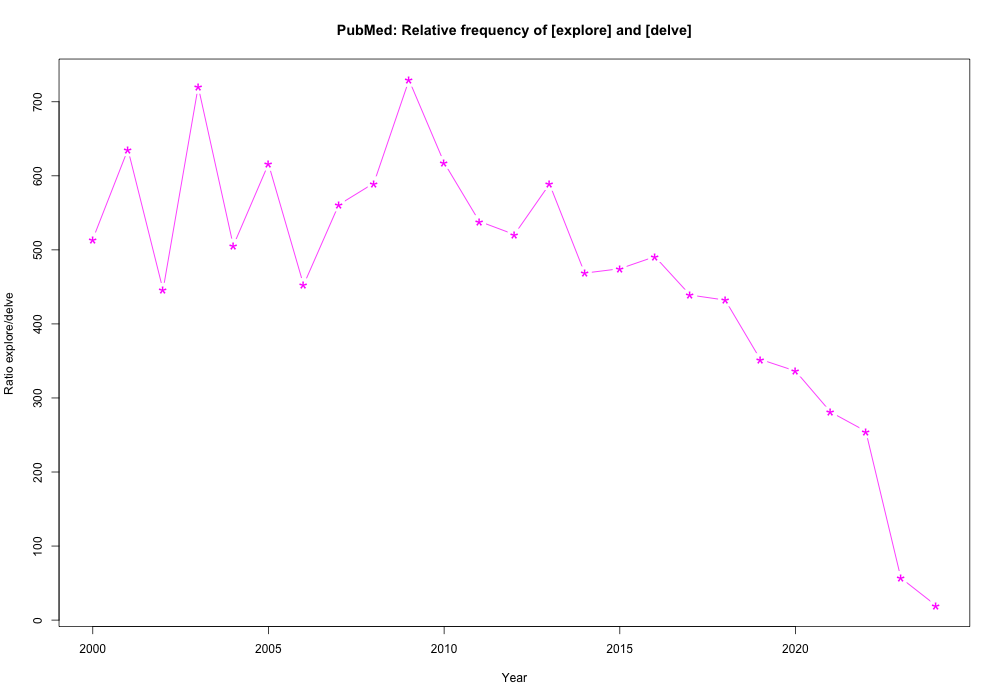

And the next thing to notice is that the changes in [delve], though extremely large in proportional terms, are small in terms of actual citation frequency, e.g. 5,526 in 2024 for [delve] compared to 108,616 for [explore]:

The proportional change for [delve] from 2022 to 2024 is indeed impressive (numbers below are from Ed Sperr's github page — the 2024 data is only for part of the year, obviously…)

- citations 629 to 5,526, factor of 8.8; citations per 100k 35.37 to 591.33, factor of 16.7

But if every PubMed citation containing a form of [delve] were written (or edited) by ChatGPT, those 591.33 citations per 100k would amount to just 0.59% of the year's citations. That's lot less than the "at least 10%" claimed by the article, which throws us back into the evaluation of their overall statistical model.

And the proportional changes from 2022 to 2024 for their other chosen words are substantially smaller, e.g.

-

- [showcase]: citations 1,900 to 4,470, factor of 2.4; per 100k 106.85 to 478.74, factor of 4.48

- [surpass]: citations 1,984 to 4,348, factor of 2.2; per 100k 111.57 to 465.67, factor of 4.17

- [emphasize]: citations 17,945 to 22,151, factor of 1.2; 1009.13 to 2372.36, factor of 2.35

- [potential]: citations 455135 to 270421, factor of 0.59; per 100k 25590.98 to 28908.95, factor of 1.13

And [delve] has been gaining in relative frequency on (for example) [explore] since 2009, long before ChatGPT was available to researchers, even though [explore] has been gaining in popularity during that time:

In the broader COHA collection, [delve] has been increasing in popularity since the 1940s:

None of this explains [delve]'s proportional change factor of 16.7 from 2022 to 2024 in citations per 100k, but it does show that there are cultural trends (even fads) in word usage, independent of recent LLM availability. And it's also not clear why ChatGPT should promote [delve] and not e.g. [probe] or [seek] or [sift] — though maybe it's because of who they hired for RLHF?

[See also "Bing gets weird — and (maybe) why" (2/16/2023); "Annals of AI bias" (9/23/2023) ]

David Marjanović said,

July 7, 2024 @ 1:27 pm

Who did they hire, and why is that important? Medium wants me to "create an account to read the full story", so all I can see is that ChatGPT is apparently well known to overuse delve very noticeably.

Jason M said,

July 7, 2024 @ 3:20 pm

Wow. Thanks for delving into PubMed to explore all these data for us!

I am puzzled by the two-century [explore/investigate] data. Why did they fall out of favor in mid 20th century?

I also wonder if [delve] was already increasing before LLM ubiquity: Is ChatGPT training text weighted for recency such that it will perpetuate whatever the latest trendy words are? If so, it would set up a positive feedback circuit that might see [delve] soon approach [explore/investigate] in frequency as the algorithm keeps training on a dataset that the algorithm itself previously wrote..

Mark Liberman said,

July 7, 2024 @ 3:48 pm

@David Majanović: "Who did they hire, and why is that important?"

See Alex Hern, "How cheap, outsourced labour in Africa is shaping AI English", The Guardian 4/16/2024, which cites an earlier claim that [delve] is common in Nigerian English, with that and several other Nigerian-English features emerging in LLM preferences because a lot of Nigerians were hired for RLHF.

And also see "Annals of AI bias".

Mark Liberman said,

July 7, 2024 @ 3:59 pm

@Jason M: "I am puzzled by the two-century [explore/investigate] data. Why did they fall out of favor in mid 20th century?"

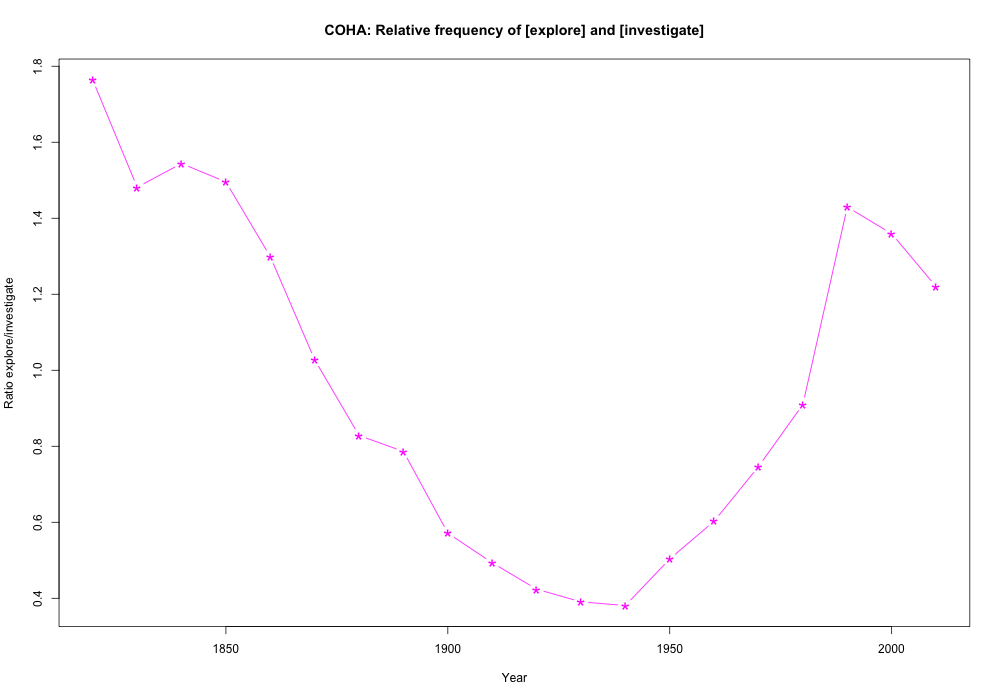

You've misinterpreted the plot — it shows the ratio of [explore] counts to [investigate] counts over the decades:

And what it tells us is that in the 1820s, [explore] was 1.76 times more frequent than [investigate]; then the ratio fell steadily until the 1940s, when it reached 0.38; and then it rose steadily until it reached 1.43 in the 2000's.

[explore] does dip slightly 1820-1940, but [investigate] rose starting in 1870 in a way that more than compensated:

Mark Davies tried hard to make COHA large enough and balanced enough to give an accurate picture of overall usage, but of course there are certainly social and contextual factors involved as well as linguistic ones, and some sampling issues as well.

Jason M said,

July 7, 2024 @ 4:39 pm

@mark liberman yes I did misinterpret the “ratio” as meaning the overall ngram-like ratio of either word relative to all other words, not of one to the other. I get it now, though still funny ups and downs. Of course, some of the swerviness of the curves is driven by the earliest datapoint for [explore] and the latest for [investigate] fwiw.

Julian said,

July 7, 2024 @ 7:03 pm

It's critical to explore these trends more fully.

Seth said,

July 8, 2024 @ 9:07 am

As we delve into these trends, we should explore the possibility that certain word-popularity of LLM's due to trainers, is also reflected more broadly in some cultures, due to increased general reach of those trainers. That is, if you take a bunch of people and give them Internet jobs in a big tech company, some of their quirky words choices might get propagated widely and picked up in general.

Cervantes said,

July 8, 2024 @ 10:59 am

As an investigator whose own papers are indexed in PubMed, and who has been watching the trends in scientific fashion for some decades, I can come up with other explanations. For one thing, it's easier to get exploratory and qualitative research published nowadays than it once was. Reviewers and editors are less inclined to insist that only hypothesis driven research is worthy of their journal — and, with open access, there are a lot more journals, including some with low standards and others that do insist on decent quality but will accept a wide range of papers. It's even possible now to publish protocols for work that hasn't been done yet. So it doesn't surprise me at all that words like "explore" and "delve" (which is a near synonym, BTW) are more likely to show up in abstracts, because that's more likely to be what the paper is doing.

Kenny Easwaran said,

July 8, 2024 @ 1:25 pm

What might be particularly useful is checking whether some of the most distinctive changes in word frequency, like "delve", "crucial", and perhaps "important" (negatively), are strongly correlated with each other. If so, then that's a good estimate of some sort of not-too-edited use of LLMs. (Which could of course either be for directly writing publication-mill quality papers, or for taking papers with high quality ideas written by non-fluent writers and turning them into fluent documents.)

[(myl) FWIW, we can compare [delve] and [crucial] with [delve] AND [crucial]…]

Rick Rubenstein said,

July 8, 2024 @ 2:29 pm

I can see the pull quote already: "Study: ChatGPT provides words of 'unprecedented quality'".

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

July 8, 2024 @ 3:15 pm

Reminds me about the old lawyer joke, where the beleaguered counsellor has just witnessed his witness being shredded to mincemeat by opposing counsel on cross-examination.

The witness gets off the stand, sits down at counsel table, and whispers in his lawyer's ear, "How'd I do?". The attorney sighs and responds, "Incredible, you were absolutely incredible.".

Julian said,

July 9, 2024 @ 4:09 am

@Seth, "some of their quirky words choices might get propagated widely…."

Maybe this is why, in bureaucrat- and consultant-speak, I now see the word "critical" with fingernails-running-down-the-blackboard frequency.