Text trumps art

« previous post | next post »

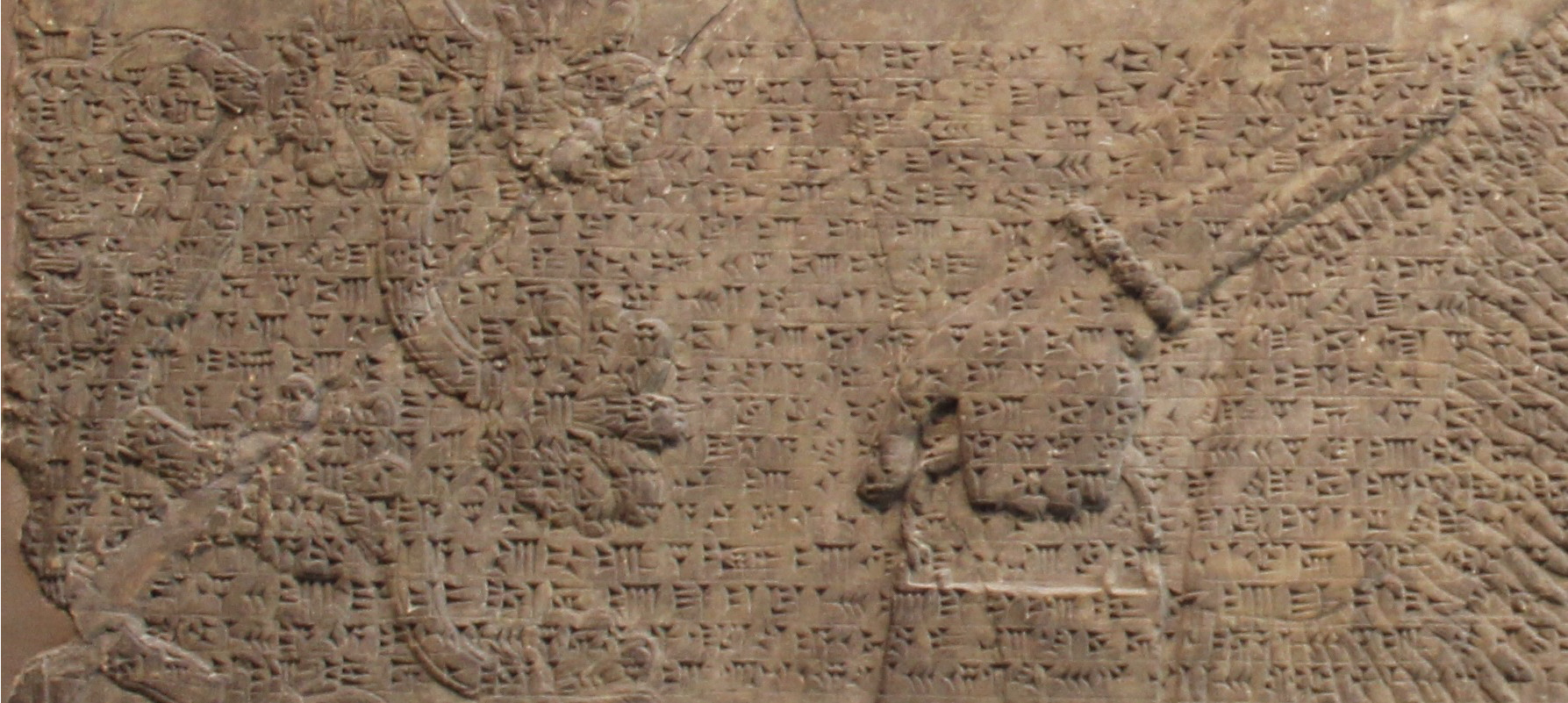

On a visit to the British Museum last week, Zihan Guo spotted this captivating relief in the Assyrian collection. You may not be able to see it upon first glance, but she was especially transfixed by the inscription running midriff on the eagle-head figure:

The inscription is easier to see in this Flickr image.

I asked Hiroshi Kumamoto what's up with writing all over the artwork?

He replied:

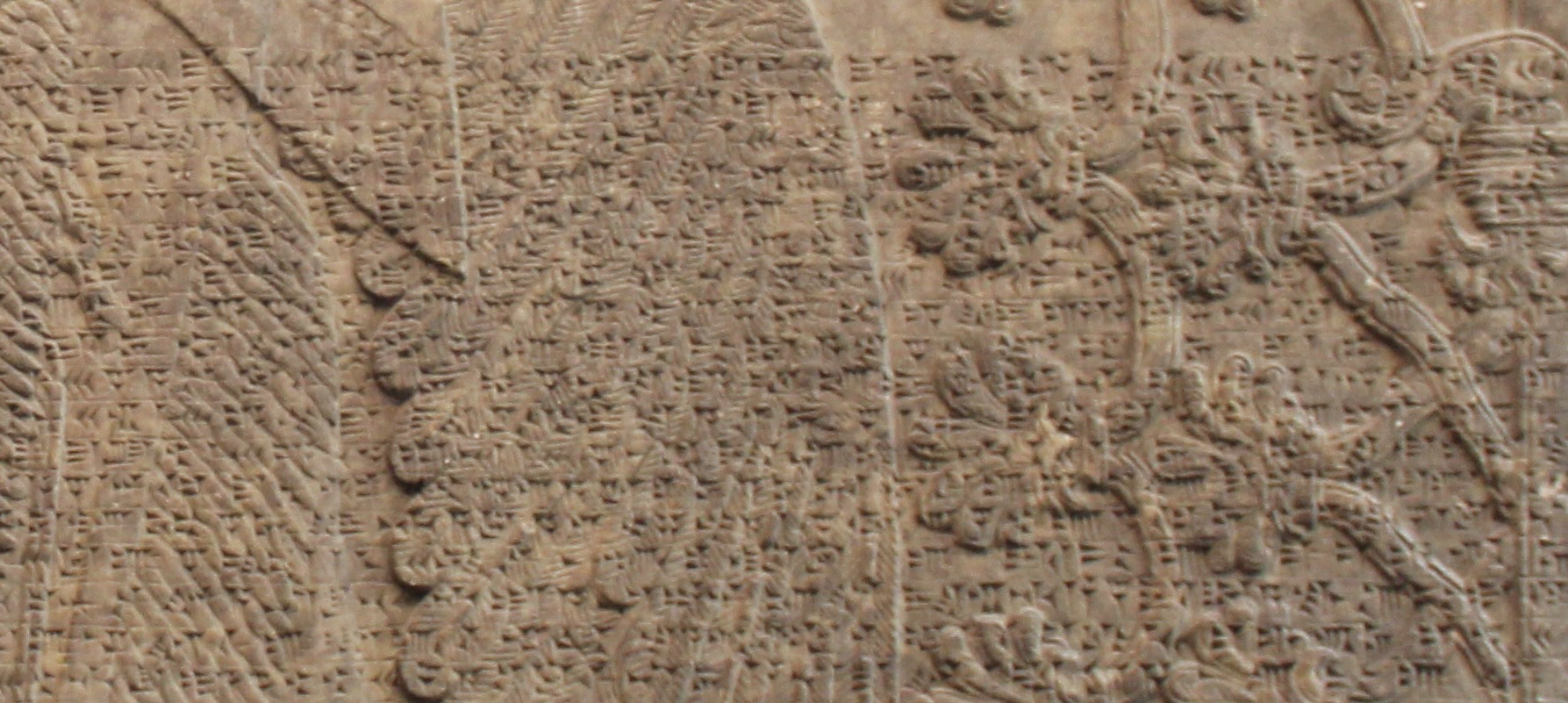

The picture seems to be one of the panels in the NW palace of Nimrud. The inscription must be the so-called "Standard Inscription" which is repeated with little variation.

For more information on the inscriptions, see this work (pdf for download) on them.

And here's the accompanying explanation:

Hiroshi further explained:

If it is correct that the reliefs and inscriptions are from the NW Palace of Nimrud, it comes from the reign of Ashurnasirpal II in the 9th C BCE (see the section of "Palace of Kalhu" in the Wikipedia article.

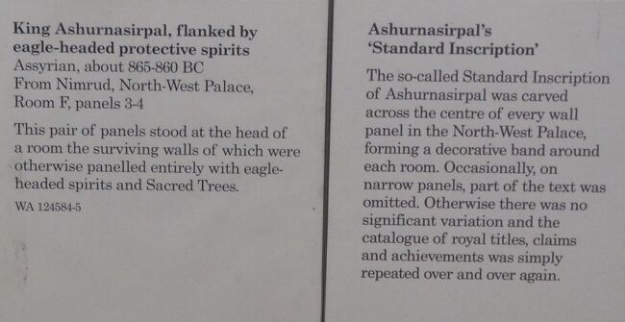

Chinese officials, scholars, artists, and emperors did the same thing to the most famous art of their land:

Presumably, their imprimaturs (!) enhanced the value of the work.

So far as I know, the most (in)famous emperor for adding his writing to art was Qianlong (1711-1799; r. 1735-1796; emperor emeritus 1796-1799), of whom Hajni Elias has said:

Yes, without a doubt it was Qianlong.

Not only his seals but he had no qualms having his poems (much of which, according to the late Prof. Frederick Mote, were substandard and I cannot agree with him more) inscribed on beautiful objects such as the Song Guan vase in the British Museum (photos and description, including reference to Qianlong's poem inscribed on the bottom, may be found here).

In fact, I often challenge my students, offering them a reward, if they can find a piece from the Imperial collection that does not bear Qianlong's signature.

What an insufferable egotist!

Selected readings

- "Language nudges Art"

- "Mandarin translation issues impeding the courts in New York" (6/20/24) — see the comments for the meaning of "chop", i.e., "seal"

Victor Mair said,

July 6, 2024 @ 4:36 pm

From Bob Mowry:

Yes, Qianlong impressed more seals on paintings in the Imperial Collection than any other emperor–by far! A painter and calligrapher–if of modest talent–Qianlong was also a collector; he added more works of art to the Imperial Collection than any other emperor. A connoisseur, he loved the collection and enjoyed looking at works from it, which he did frequently. He typically added seals to works of painting and calligraphy when he viewed them, and he occasionally had an inscription and seals carved into ceramics and jades that he particularly loved.

It should be noted that many of the Qianlong seals that appear on works of painting and calligraphy are "cataloguing seals", rather than personal seals; such cataloguing seals indicate that a particular work has been officially recorded, described, and included in one or another of the collection catalogues. Many such works bear several different cataloguing seals as well as personal seals.

The most famous of the Qianlong painting catalogues is Shiqu Baoji 石渠寶笈; there are several "series" or "continuing volumes" of the Shiqu Baoji 石渠寶笈續編 etc.

Anyone doing research on a painting with Qianlong catalogue seals must check the catalogues to see if the painting is included therein. If the painting is not listed there, then the seals are surely spurious; if the painting indeed is listed therein, one must still check the authenticity of the painting and the seals to make sure neither painting nor seals is a clever fake. The seals on any work still in the Imperial Collection (i.e., in either Palace Museum, whether Taipei or Beijing) are virtually above suspicion; it's paintings with such seals now outside that collection that must be scrutinized and verified; those in major museums have been so verified–Boston, Met, Kansas City, Cleveland, Freer, etc.–but others turn up from time to time and must be scrutinized.

Several other emperors impressed seals on works of painting and calligraphy–Ming Xuande, Qing Kangxi, and Qianlong's successors–but because of his interest in and love of the arts, Qianlong impressed more than any other emperor; indeed, more than any other individual.

Private collectors who impressed seals on a number of fine paintings include Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590) and his grandson Xiang Shengmo 項聖謨 (1597–1658). Xiang Yuanbian was arguably the best and best-known private collector of Chinese painting and calligraphy during the Ming dynasty. And An Qi 安岐 (c. 1683–c. 1744; also known as An Yizhou 安儀周) was arguably the best and best-known private collector during the Qing dynasty. An Qi was Korean; in his youth he accompanied his father to Beijing and remained in China the rest of his life. A salt merchant, he became exceptionally wealthy through the salt trade.

Much of the Xiang Yuanbian and An Qi collections eventually ended up in the Imperial Collections.

Victor Mair said,

July 6, 2024 @ 4:41 pm

Remember to click on the images to embiggen if you want to see the details (e.g., cuneiform inscriptions) up close.

BTW, what is the object the muscular eagle-man is carrying with his left hand?

Daniel C. Waugh said,

July 6, 2024 @ 5:47 pm

On the object in left hand, another Wikipedia source:

Other depictions of genii show them holding what appear to be a pine cone and a pail. These two elements are commonly associated with the Tree of Life. Many interpretations have stated that the depiction is of the genii fertilizing the tree and tending to it. Other interpretations place the pine cone as an object known as a mu-li-la, and in conjunction with the pail, is used to avert evil forces whether real or supernatural. Another interpretation stated that the tree and sun above it represent the distinction between heaven and earth. Some theories state that these symbols are directly related to the cult of Assur, where the sun symbolizes Shamash the sun god and the tree symbolizes Assur himself. Therefore, it is inferred that the genii protecting the tree represent the supernatural forces that the Assyrians believed were protecting the earth and more importantly the Assyrian Empire.

[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winged_genie]

On Qianlong's collections, there is quite an amazing array of Buddhist sculptures in the Forbidden City museums, each carefully tagged with information as to the donor, date (many from centuries earlier), or whatever. We saw an striking selection (which also included the 18th-century high quality "replicas" being cast for the court) there a good many years ago.

katarina said,

July 7, 2024 @ 1:56 am

When I was a college student in Taiwan many decades ago in the 1950s, my mother had me take lessons in Chinese traditional painting and calligraphy from Prince Pu, or Pu Xinyu (also known as Pu Ru), a cousin of the last Qing dynasty emperor, Pu Yi. Traditionally, one was supposed to first show respect and obeisance to the teacher by bringing presents and kowtowing to the teacher. We were poor refugees then and I could only bring one chicken cooked by my mom and a small fee. She did not have me kowtow because she said that if I kowtowed, he would treat me as an apprentice and would have me do tasks around the house such as wash his windows. The painting and calligraphy lessons were given in quite a different manner than what I had expected from my Western schooling. Each lesson was held with my fellow "classmates" , four or five rich socialite ladies, wives of top officials and bankers, all beautifully made up and coiffed and fashionably dressed in the Chinese qipao (high collar dress with side slits), and myself standing before his square low table (like a coffee table) on which was the "rice paper" on which he painted and the dish of black ink and the little ceramic bowls of water in which he swished his brush. He would be seated on the floor behind the table. Plump and fiftyish then, he would chat with the rich fashionable ladies (among whom I was timid and mute) while he painted continuously, and a beautiful black and white painting would materialize before our very eyes. You learned by watching him. You would be given one of his many paintings thus generated to take home and paint your own copy of the painting. During the next lesson I would show him my "homework" and he would point out its many deficiencies. Of course my copies were wretched and he would look at me with pity as a poor ignorant misbegotten Westerner, even though I was Chinese. To come to the point, I learned a lot about Chinese painting from these sessions, but one of the most important things I learned about Chinese traditional painting was his remark that text trumps art, or rather, text trumps picture, trumps painting. Although he was arguably the greatest traditional Chinese painter of the twentieth century, he said of himself: "Painting is not my real interest." We understood that as a refugee he had to do it for a living. "What I am really interested in is poetry. I would like to teach you poetry, not painting. Painting is subordinate to poetry. A painting is just to express the spirit of a poem. A painting is of no value if it doesn't have a poem on it." He himself was an accomplished poet. By this criterion, the paintings of Qi Baishi, one of the most celebrated painters of that period, would not be of the highest value. Qi's paintings didn't have poems on them because Qi didn't receive a classical education.

Victor Mair said,

July 7, 2024 @ 6:12 am

@katarina

Extraordinarily precious memories elegantly and poetically expressed.

fēichánggǎnxiè 非常感謝 ("thank you so much")!

I know a few other Westerners who studied with Prince Pu in those days, but they were male, and they learned how to read Classical Chinese / Literary Sinitic from him — the traditional way, not the analytical way I teach it. They are all famous Sinologists now.

Victor Mair said,

July 7, 2024 @ 11:22 am

There were two Manchu Prince Pu scholars in Taiwan back in those days

From Robert Eno:

I think you’re confusing two different princes. Prince Pu (Puru 溥儒) was an artist. The classicist who trained foreigners in 四書五經, etc., was Yuyun 毓鋆, often referred to as Yulao 毓老 by his students. Puru was a generation up genealogically, I believe. Looking at Wikipedia, Puru died in 1963, which is when Yulao was just beginning to train Western sinologists; Yulao (who died in 2011 at 104) occasionally spoke of him.

From Edward Shaughnessy:

In your comment to Katarina, I suspect you were mixing up the two Manchu teachers in Taiwan in those days: Aisin gioro Puru 愛新覺羅溥儒 and Aisin gioro Yuyun 愛新覺羅毓鋆. Puru, of course, was the painter. Yuyun, better known as Yu-lao or "the Manchu Prince," was the classicist, teacher of your colleague Nathan Sivin and many others.

katarina said,

July 7, 2024 @ 2:34 pm

@Victor Mair

Thank you, Professor Mair, for your kind appreciation.

There are two additional tidbits that may be of interest, one about

language, and one about talent and worth.

The conversation at Prince Pu's once came to the Wuchang Uprising of 1911, an event which ended with the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty. Everyone knew from school textbooks about the Wuchang Uprising . But Prince Pu said: "It was not an uprising at all. It was the Rebellion of 1911." Uprising (in Chinese qiyi 起義 "Rise in Righteousness") made the participants heroes. Rebellion (zaofan

造反) made them villains and criminals.

Prince Pu had other pupils who came at different hours for lessons. I learned that his best pupil was a middle-aged woman. I met her. She didn't wear make-up, was not glamorous, not fashionable, just an unassuming very ordinary-looking kindly housewife. I learned that she produced the best copies of Prince Pu's paintings. This startled me because housewifery was a fate I (secretly) wanted to escape at all costs. This put it in a new light.

Yves Rehbein said,

July 8, 2024 @ 3:30 am

@VMR, "BTW, what is the object the muscular eagle-man is carrying with his left hand?

I believe journalist Graham Hancock has an answer to that. It's a bag, obviously, and from what I read it's a symbol of prosperity; maybe a gift? The shape, what could also be a rainbow or the höyük itself (Turk. "hill"), appears as early as in Çatalhöyük. Ignoring all his other claims I find this rather intriguing, but who knows.

On another note: Breaking News — Ricebag Fallen Over (China, the Onion).

Victor Mair said,

July 8, 2024 @ 11:24 am

Here is a video showing how Puru (Pu Xinyu 溥心畬) conducted his painting class:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iWJv0AnF0rU

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puru_(artist)

Victor Mair said,

July 8, 2024 @ 1:11 pm

From shaing tai:

At the beginning of the video, 溥心畬 was conducting a Chinese reading class with students from Japan and the West, as told by the.narrator. In this respect, your reply is supported by this video.

Victor Mair said,

July 8, 2024 @ 6:13 pm

From katarina, to whom I called attention to the video of Puru conducting his painting his class and asked whether she were in it:

No, I am not in it. It was probably made many years after my lessons (1951-1952), when he was not yet.a celebrity.

You can see how swift his brush strokes were. The film was not speeded up. What you see is really his speed. And you see his mastery of the brush, where a bamboo leaf can be shaped in a single brush-stroke, and where a long swift line can have many gradations of width and shades of ink, all controlled. It is calligraphic painting. All the figures, objects, and scenes came from his mind. They result from many years of youth copying masterpieces in the Imperial art collection. But no other Manchu prince achieved his virtuosity in painting and calligraphy. He used the old vocabulary of past masters to create new landscapes in the old style.

Victor Mair said,

July 8, 2024 @ 6:22 pm

From Bob Mowry:

When you wrote asking about Qianlong and his seals, I didn't realize that you were referring to those on the Han Gan "Shining Light of the Night" painting now in the Met's collection. There indeed are a number of Qianlong seals on that painting–including both personal and cataloguing seals (including the Shiqu Baoji 石渠寶笈 seal)–but there also seals but other collectors and connoisseurs, as it's an old, Tang painting and has historically been prized and celebrated.

The painting has a number of colophons with yet more seals and inscriptions. A click on the following link will take you to a list of all the seals and their owners as well as transcriptions and translations of the inscriptions and colophons (including Qianlong's). I hope this will prove interesting and useful:

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39901

The painting previously was in the collection of Sir Percival and Lady Sheila David, London; the Met acquired it in 1977–a wise and very astute acquisition on the part of the Met.

Philip Taylor said,

July 9, 2024 @ 1:52 am

"The painting previously was in the collection of Sir Percival and Lady Sheila David, London; the Met acquired it in 1977–a wise and very astute acquisition on the part of the Met" — an unfortunate collocation. In the context of London, "the Met" is the Metropolitan Police, the dodgier elements of which might well perceive the acquisition of the painting as a wise and very astute move !