Ron's Princibles

« previous post | next post »

Sunday's post on "Listless vessels" opened with this clip:

about what are you trying to achieve on behalf of the American people

and that's got to be based in principle

uh because if you're not rooted in principle

uh if all we are is listless vessels that just supposed to follow

you know whatever happens to come down the pike on Truth Social every morning

that- that's not going to be a durable movement

And in the 30th comment, Yuval wrote

FWIW, both utterances of "principle" sound like 'princible' to me.

He's absolutely right — but what those two words "sound like" leaves an important theoretical (and practical) question open.

First, let's look at (and listen to) Ron's "principles".

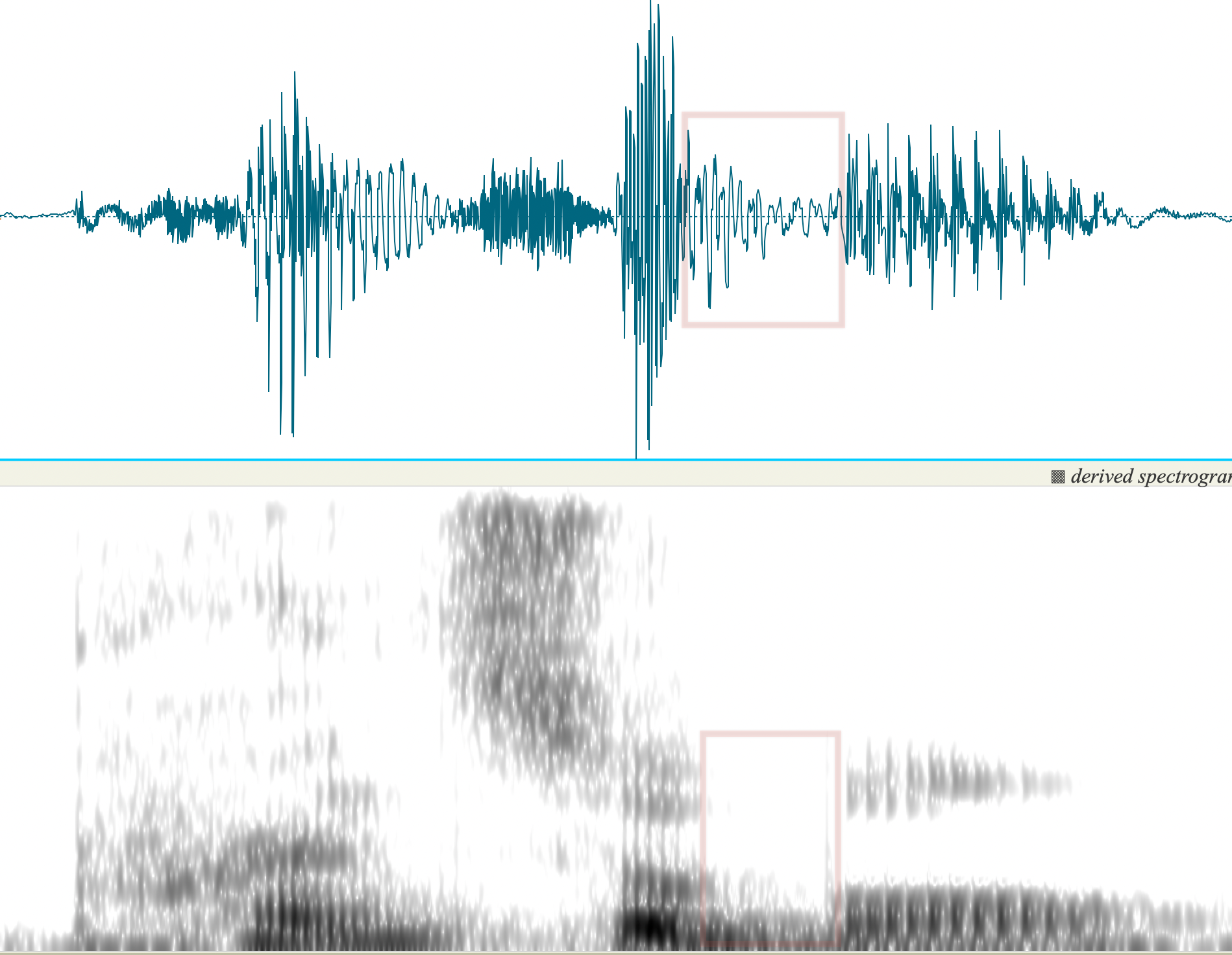

Here's the first one, followed by an image of the waveform and spectrogram, with the closure of (what the dictionary says is) the /p/ of _ple in outlined in red:

If you're at all familiar with interpreting images of waveforms and spectrograms, you'll see that the voicing continues throughout the closure, and the release is weak, short, and voiced (unlike the burst of the word-initial /p/).

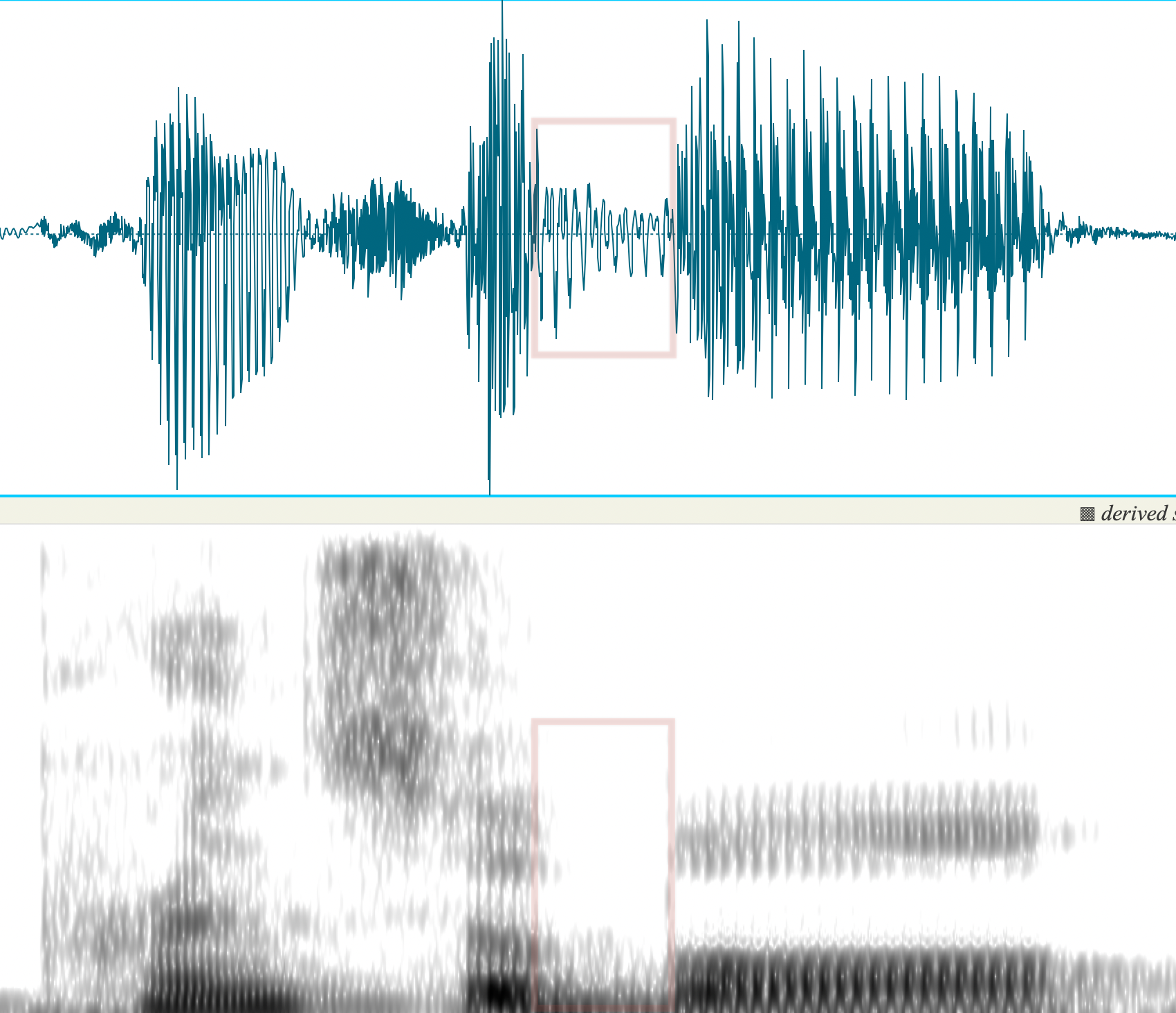

And here's the second one:

Same thing.

This is an instance of a much more general fact about English in general, and American English in particular — consonants are "lenited" (== weakened), especially in intervocalic position, when they aren't part of the onset of a stressed syllable. "Lenition" often means that voiceless stops become voiced, voiced stops become fricative-like — and more extreme changes in phonetic performance are also common.

The best-known example of this type of allophonic variation is the "flapping and voicing" of /t/, that results in "latter" sounding the same as "ladder". What Gov. DeSantis does with the second /p/ in "principle" is another example of the same sort of thing.

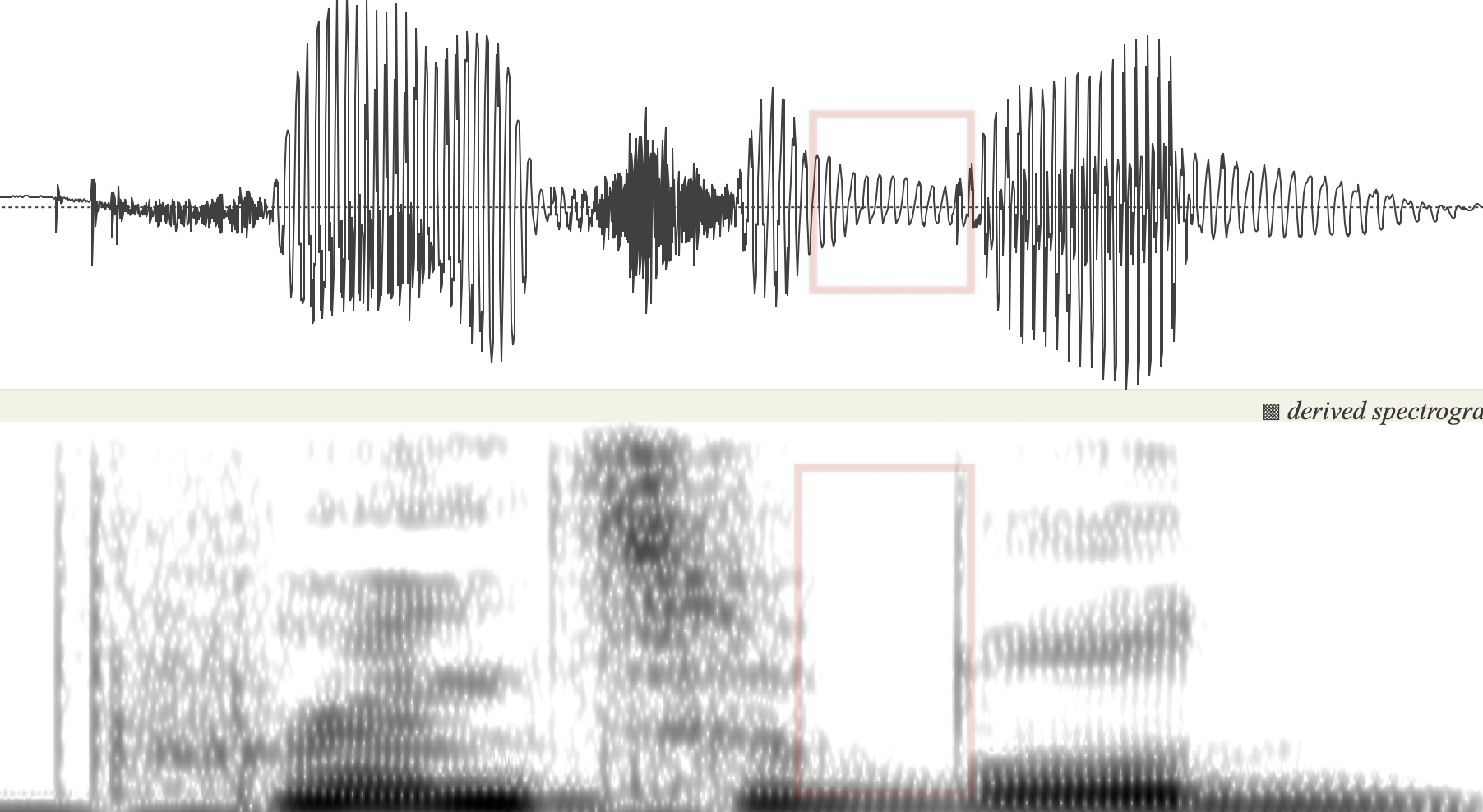

And that sort of thing happens to the word "principle" a lot. The NPR podcast corpus I've mentioned before has 2,160 examples of the word "principle", of which I selected 200 at random. Most of them exhibit a variety of lenitions in the final two syllables — which are sometimes further reduced to something like [svl̩] in IPA-ese. Gov. DeSantis' less-reduced pattern is common — here's Barbara Bradley Hagerty, from "Catholics Split On Obama's Birth Control Decision", NPR All Things Considered 2/10/2012:

which has at its core a principle dear to the church

And zeroing in on "principle":

Again the realization of the /p/ is voiced throughout, though there's a slightly stronger release than in the DeSantis examples.

So what's the "important theoretical question" that I brandished at the start of this post?

Have these instances of (the phonological category of) consonant /p/ really turned into instances of (the phonological category of) consonant /b/? Or are these examples just one region in a spectrum of variably-lenited and co-articulated phonetic implementations of the abstract phonological pattern in question?

In other words, is (this kind of) allophonic variation a mapping of symbols to symbols? Or is it just of part of the (necessary) translation of symbols into (articulatory and acoustic) signals?

In my 2018 paper "Towards Progress in Theories of Language Sound Structure", among other places, I argue that the null hypothesis should be the phonetic implementation theory, claiming that in every case where anyone has looked seriously into patterns of allophonic variation, that hypothesis wins empirically. In the cited chapter, I look in depth at some phenomena in English and in Spanish — many other cases in many languages have been studied over the years, e.g. Jiahong Yuan and Mark Liberman, "Investigating Consonant Reduction in Mandarin Chinese with Improved Forced Alignment", InterSpeech 2015.

What does this mean about Ron's "princibles"? I predict, in advance of doing the work, that a large sample of the phonetic implementations (by American speakers) of the second /p/ in "principle", although often voiced, would be different from a comparable sample of implementations of the /b/ in "sensible" — and that the differences would not fit very well with the hypothesis that some instances of /p/ were simply turned into /b/. And similarly for other near-minimal-pairs.

Coby said,

August 22, 2023 @ 1:27 pm

This phenomenon may not be all that recent OR American. Consider the uncertainty of the name of the composer John Dunstable/Dunstaple.

Peter Grubtal said,

August 22, 2023 @ 1:40 pm

As Coby says, the instability voiced/unvoiced is a frequent phenomenon in some of the languages with which I am familiar.

In German we have Habsburg/Hapsburg Kebab/Kebap. In Japanese the voicing in jukugo is often part of the formal language.

The above essay seems to be over-theorising a very natural phenomenon.

Mark Liberman said,

August 22, 2023 @ 2:50 pm

@Peter Gurtal: The above essay seems to be over-theorising a very natural phenomenon

Intervocalic consonant lenition is obviously a natural phenomenon — I cited examples in Spanish and Mandarin, but many other languages share similar effects — nearly all languages, at some points in their histories. The question is, whether (or when) to model this as a pattern of symbolic substitution, or as contextually-defined patterns in symbol performance?

David Marjanović said,

August 22, 2023 @ 5:12 pm

No. In German we have Habsburg, with a long /a/ as graphically shown by the b even if you don't distinguish /b/ and /p/ in this position (I do). Kebap is the official Turkish spelling, because Turkish has word-final devoicing and spells it out; -b is a partial restoration of the Arabic original (or was it Persian).

I would say it depends on whether your prediction comes true. If it does, /p/ and /b/ remain distinct in this context, even if they come out not as [p] and [b], but as [b] and [β] or whatever. If it does not, then /p/ is banned in this position for the speakers in question and has been replaced by /b/.

Similarly, with /t/- and /d/-flapping, some insist that ladder remains distinct from latter in that the former has a longer vowel (in other words, latter retains pre-fortis clipping despite the absence of a phonetic fortis). Others insist they're exact homophones. In 2006 I met someone aged around 60 who once misunderstood his son over this: he understood write in but his son had meant ride in, so maybe there's a recent merger here that's still spreading.

The answer may lie in the middle, too. There's a series of studies on word- or syllable-final fortition in a few European languages that found there's a partial merger: the speakers can hear whether another speaker intended the fortis or the lenis some 2/3 of the time, and the spectrograms bear this out. Apparently that disproves whole classes of theories of phonology.

Thomas Hutcheson said,

August 22, 2023 @ 10:07 pm

What is making "vulnerable into "vunerable," and "library" into "libary" called?

Jarek Weckwerth said,

August 23, 2023 @ 4:35 am

If I was feeling flippant, I would say it depends on how much (and what kind of) statistics you throw at it.

But in principle ;) I'm in total agreement with Mark. The null hypothesis should always be that these kinds of things are subphonemic (or, perhaps, as David suggests, they start as subphonemic), and are overinterpreted (by native speakers in particular) as phonemic.

One of my own favourite examples is the "epenthesis of /t/" story in words such as prince which was pretty standard in phonology until that seminal article (I can look up the details if someone needs them, but it was I think from Haskins Labs) that showed that the /t/s are actually different in prince and prints on a number of counts.

Mark Liberman said,

August 23, 2023 @ 5:42 am

@Jarek Weckwerth: If I was feeling flippant, I would say it depends on how much (and what kind of) statistics you throw at it.

True enough. And it also depends on what range of hypotheses you entertain (though I suppose that "what kind of statistics" covers that…)

We're wandering into the area of "near mergers", where the psychology and sociology of phonology get complicated.

Cervantes said,

August 23, 2023 @ 7:19 am

In Puerto Rico and, I believe, most Spanish, the intervocalic d becomes a minimal /ð/. As with all of these examples I believe it's basically laziness — just reducing the need to adjust the vocal apparatus.

Mark Liberman said,

August 23, 2023 @ 8:13 am

@Cervantes: As with all of these examples I believe it's basically laziness — just reducing the need to adjust the vocal apparatus.

"Laziness" is unduly judgmental, IMHO. Rather call it "rationality in action".

The first point is that speech pushes the articulatory system to its limits — the physics and physiology of the situation force coarticulation and reduction to take place, and the only question is where and when and how much.

And in speech as in all actions of animals, the goal is joint optimization of efficacy (here the rate of effective information transfer) and effort (crudely, calories/time/cognitive load expended).

You can talk faster, at the expense of more co-articulation and reduction; or you can talk more slowly and carefully, at the expense of wasting time, perhaps boring your audience, and raising the question of why you're doing it.

Obviously, where you position yourself on this continuum depends on your skills, the contextual information density of your material, etc.

Cervantes said,

August 23, 2023 @ 8:34 am

I actually majored in theater as an undergrad and worked as a stage actor for a couple of years. We learned to pronounce very precisely so I know that it is actually difficult and requires practice and effort. "Laziness" is a shorthand way of explaining that. True, there's no reason to make the effort as long as you can be understood. Stage actors have to simultaneously speak reasonably fast, but without too much reduction. It's a skill. It comes off as unnatural on film or video, however, where you want more verisimilitude.

Coby said,

August 23, 2023 @ 8:52 am

Re "laziness": Cubans (and other Hispano-Caribbeans) have a reputation for speaking "lazy" Spanish, for example pronouncing sábado as sao. But Cuban singers enunciate lyrics very clearly. This is different from American (and perhaps other English-language) pop singers, whose songs are often hard to understand without subtitles.

Tom said,

August 23, 2023 @ 10:09 am

/p/ and /b/ show up in German nightmare, *Albtraum*, and now has a dictionary variant *Alptraum*, because it's said to sound like the *Alps*. In Germany, spelling reformers of the 1990s introduced dictionary variants for words, because (children, turned) adults confused sound and acustic “false friends”.

To my knowledge, there are no flips in *Habsburg*. Why? The spelling reformers were criticized for nitpicking words, leaving out an entire dictionary that could have fallen under the same schemes.

On kebap or kebab, the https://en.langenscheidt.com/german-english/search?term=kebap /p/ doesn't show in *Langenscheidt*, while it does in https://www.dwds.de/wb/Kebap , a German corpus, *note* the (blue) statistics graph on the word frequency over time; also, the *Herkunft * references to Arabic and Turkish.

Personal opinion: Spelling errors in school exams are said to have increased, many word origins have been lost by the spelling reforms, French accents got eliminated, German speech has not gotten any easier; English words.

However, if speakers say /b/ instead of /p/, they might be just tired? Occam's / Ockham's razor?

Barbara Phillips Long said,

August 24, 2023 @ 3:15 pm

@Thomas Hutcheson —

I don’t know what the phenomenon is called, but using “libary” for “library” often, in my experience, comes from speakers who are not particularly eager or adept readers. I wish I could say that that is a solid hypothesis, but the “library” speakers may say “often” instead of “offen,” and I was taught that the t is silent in the word often.

Then there’s February. Despite being drilled in the “proper” pronunciation by an autocratic junior high English teacher (who also obsessed over pronouncing horrible and Tuesday), I find that when I am not paying particular attention, the name of the second month comes out “Febuary” despite myself. So there does not seem to be a reliable correlation between skill with reading (and familiarity with the visual appearance of the spelled word) with the pronunciation of words where some letters are commonly elided or altered during speech.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

August 24, 2023 @ 3:19 pm

Sorry I did not catch some spell-check unhelpfulness. I had written that “libary” speakers may say “often.”

SP said,

August 24, 2023 @ 4:11 pm

As I understand it, this same process was the origin of initial consonant mutation in the Celtic languages, which is certainly a mapping between symbols. (Identical sound changes also occurred word-internally, giving e.g. Welsh *disgybl* from Latin *discipulus*.)

JPL said,

August 24, 2023 @ 5:02 pm

The elision of a sound in the pronunciation of a word, compared to the citation form, is also called "syncpe" — sorry, "syncope".

I think Mark's hypothesis is the correct one. What's important is to distinguish between, on the one hand, what is being referred to in the world — in this case articulatory actions, their acoustic results (from a hearer's point of view) and the categorical structures that make the instances in action possible; and on the other hand, the notations used by the linguist to describe the realities. In the case of the traditional distinction between narrow (phonetic) transcription and broad (phonemic) transcription, there is a distinction in the meaning and the reference of the expressions: in the case of narrow transcription, differences in symbol indicate differences in the articulatory and acoustic facts in the world, in terms of relevant properties of the articulatory actions (place, manner, etc.) and perceivable results; in the case of broad transcription, differences in the symbols (in the notation) indicate differences in the relatively small number of types of sound the language uses to distinguish the "Bloomfieldian forms" of the language (used to distinguish words and morphemes). Particular articulatory actions, as examples of purposeful action, are instances of action schemata (like e.g., your backhand stroke) that have the internal structure of the category, a relevant property of which is that there is variation in the properties of the instances due to context of application, in this case phonetic context (allophonic variation). So instances of sounds in speech (phones) are instances of real categorical structures, and an instance of a purposeful /p/ may have articulatory and acoustic properties similar to an instance of a different "category" /b/, and it would be interesting to see if the physical properties are or are not completely equivalent. I could give an example of evolution in a language's sound system due to "phonemicization" of allophonic differences, but this comment is too long. BTW one can describe the instances of allophonic differences by switching to a narrow transcription, or one could simply describe the articulatory nuances using natural language (e.g., "palatalization", "fronting", "continuity of voicing", etc.)

Taylor, Philip said,

August 25, 2023 @ 5:06 am

Libary speakers / often / February / Tuesday /etc.

Introspections leads me to believe that where I was taught a pronunciation at school, I stuck with it rigidly (/ˈlaɪ brə ri/, /ˈfeb ru æ ri/, /ˈtjuːz deɪ/, / ˈkʌn dɪt/), whereas when I learned a word informally (colander, often, England) I am far more likely to have adopted a spelling pronunciation in later life, once such concepts entered my stream of consciousness.

David Marjanović said,

August 25, 2023 @ 7:46 am

In all of* Castilian, Catalan, Basque and probably a few others in the region, but not Portuguese, b d g come out as approximants, [β̞ ð̞ ɰ], except after pauses and nasals, where [b d g] survive, as (AFAIK) they do in deliberately slow & clear enunciation. This has not created new phonemes.

* Except where even further reduction has taken place; Cuba has been mentioned, and [ð̞] has disappeared in Granada, so that en Granada no hay nada famously comes out as en Graná no hay na. Or so I've been told. – French has been through a version of this, too: most of the time, Spanish d corresponds to zero in French, and Spanish b to v.

It's the other way around: the pre-reform version is Alptraum, and the reformed version is Albtraum; it was reformed to remind people of the etymology, which contains the cognate of elf (and oaf).

However, unlike most other native speakers, I would not pronounce these the same… I have a pure fortis/lenis distinction without voice (or aspiration). Fortunately, this word isn't in my active vocabulary anyway. I'd say "I dreamt bad(ly)".

It is interesting that the reform left haupt- ("main") alone. The /b/ is uncontested in Haube "beanie".

No, that's optional.

(Most parts of the reform, actually, were optional from the start or were made optional at the last minute in 2005.)

Uh, what? It was a spelling reform, not a language reform. There is nobody who could have the authority to change what does or does not count as Standard German.

No, that's loss of aspiration in /sk/. Most of English has that, too, it just doesn't spell it out.

Tom said,

August 25, 2023 @ 7:51 am

@Philip Taylor

Does school teach schedule or skedule, issue or isshoo, /ˈpraivit/ or /ˈpraivət/?

YouTube youngsters keep saying, some ways come across as “old, that posh” and they convey the idea, to dismiss RP and BBC English, to accept dialects and variants.

Tom said,

August 25, 2023 @ 8:53 am

On German:

That's right, “the pre-reform version is Alptraum”, mixed that up.

“… that the reform left haupt- ("main") alone,” is symptomatic for how (social) reformers generally approach problems, namely having no approach, no testing, no proven system. Spaghetti approach that is.

The proponents then and now lack the intellectual wisdom and foresight. Unlike Webster, the one-man dictator with having the benefit of decades, the German reforms were done by committee, by bargains, and groupthink, with politicians at the table, in other words, done by a Politburo. And they claim to be linguists, rather than dictionary bureaucrats, the sort of Trottel type, the mundane.

For example, Swiss writers noticed early on, the reformers couldn't care less about Swiss German conventions, so Switzerland added an additional four years of corrections (2006–2009/10) to the ten-years of corrections. And the Germans then complained about that, Switzerland would become an island … some sort of Hong Kong/Taiwan.

As I said, the saying is, spelling errors in schools have increased—and it's said, the reforms would make it easier.

My own mixing of /b/ and /p/ in Alb/Alp shows it.

Taylor, Philip said,

August 25, 2023 @ 4:48 pm

Tom — "Does school teach schedule or skedule, issue or isshoo, /ˈpraivit/ or /ˈpraivət/? ". I honestly don't know (or perhaps don't remember). The four words I listed I clearly recall being taught at school (and being told how important it was to sound, for example, the first "r" in "February, and how important it was to forget the spelling of "conduit" when saying the word out loud). For "schedule", I was long aware of this being used in two different senses with two different sounds — "Schedule A" (which I think had something to do with taxation) was /ʃe dʒuːl/; "schedules", on the other hand, which were similar to rotas, timetables, etc., were /ˈske djuːlz/. About "issue" I am ambivalent. But "private" is definitely /ˈpraivit/, just as "privet" is /ˈprɪ vɪt/, not /ˈprɪ vət/.

SP said,

August 26, 2023 @ 5:19 am

@David Marjanović:

>>Identical sound changes also occurred word-internally, giving

>>e.g. Welsh *disgybl* from Latin *discipulus*.

>No, that's loss of aspiration in /sk/. Most of English has that, too,

>it just doesn't spell it out.

I meant /p/ > /b/ in the final cluster of *disgybl*, the same change as in “princibles”.

David Marjanović said,

August 26, 2023 @ 12:45 pm

Oops! Yes, that's exactly the same. :-)

Taylor, Philip said,

August 27, 2023 @ 2:10 pm

Except, of course, when speaking of a scheduler (e.g., a computer program which I use to assign bowls matches to days / time slots / rinks), when I invariably think of the word as /ˈʃe dʒə lə/. So much for trying to be consistent !