Used to be a bun

« previous post | next post »

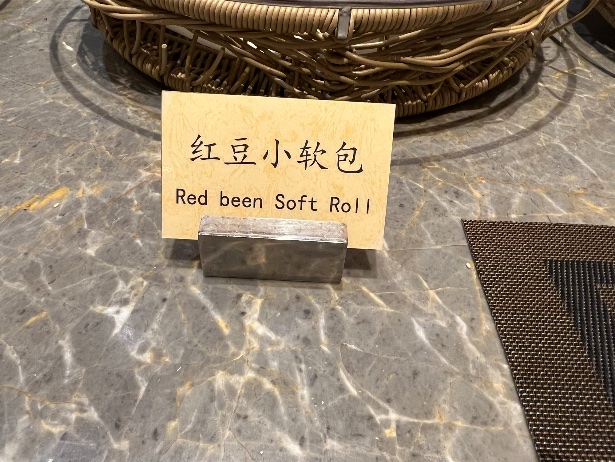

Dunhuang (see here and here) is turning out to be a Chinglish goldmine. Maybe that's because it's so far out in the remote, desolate, desert northwest.

The Chinese label says:

hóngdòu xiǎo ruǎnbāo

紅豆小軟包

"red bean small soft bun"

The printing is nice.

Selected readings

- "Somking" (7/7/23)

- "More savory Chinglish from Dunhuang" (7/9/23)

- "Baozi: The stuffed, steamed bun becomes a meme"

Philip Schnell said,

July 12, 2023 @ 2:08 am

Given your research, I’m sure you’re already aware of this, but it may be of interest to anyone curious about that little-known region—there’s a historical novel by the Japanese novelist Yasushi Inoue called 敦煌 (“Tun-Huang,” in the English translation by Jean Oda Moy) that’s an imaginative recreation of the provenance of the Dunhuang manuscripts through the eyes of a scholar who sleeps through his civil-service exam and ends up making his way west to pursue his fascination with the Tangut script. It’s a delight.

Hiroshi Kumamoto said,

July 12, 2023 @ 7:41 am

And a movie based on the novel.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hztD944M-S0

The late James Hamilton said that he was delighted to watch the film on a flight to Japan.

The novelist remarked somewhere that in preparation for the novel he hand-copied (in a pre-Xerox era) Prof. Fujieda Akira's (藤枝晃) "沙州歸義軍節度使始末" in 4 installments in Tōhō-Gakuhō 東方学報 (Kyoto), 1941-1943. In the late 70s when I started to work on Dunhuang MSS it was still the only reliable general survey of the history of Dunhuang in the 9th and 10th centuries.

Victor Mair said,

July 12, 2023 @ 8:51 am

We are so fortunate to have Yasushi Inoue's historically grounded novel about Dunhuang and its English translation by Jean Oda Moy.

I had the privilege of knowing the great Dunhuang scholar (Tonkō gakusha 敦煌学者), Fujieda Akira, and visiting him in his Kyoto study, where he showed me how to detect forged Dunhuang manuscripts and revealed other arcana of Dunhuangology.

Hiroshi Kumamoto, an outstanding specialist of Khotanese and other premodern Iranian languages, was the first UPenn graduate student on whose doctoral thesis committee I served, worked extensively on Dunhuang materials.

My latest PhD student, Nikita Kuzmin, who successfully defended his dissertation two weeks ago, is a specialist on Tangut inscriptions, including those from Dunhuang.

Denis Mair said,

July 12, 2023 @ 5:03 pm

Your readers may be interested in knowing that 高尔泰 Gao Ertai's account of his years doing research at Dunhuang can be found in his autobiography《寻找家园》. His experiences give a window into the Chinese side of Dunhuang Studies during the leftist period. After nearly starving in a prison camp, Gao was fortunately appointed as a researcher at Mogo Grottoes in 1962. His research on "transformation texts" was permitted, because texts in Tang vernacular were considered as precursors of literature for common people. The research was compatible with his personal interest in aesthetics, but he wisely kept his theoretical interests to himself. After establishing a research facility in a Daoist temple near Mogao Grottoes, the provincial government became preoccupied with internal struggles and left the facility to pursue its work without interference for several years. Gao recounts his years at the Mogao Grottoes in the following chapters of his memoir: "敦煌莫高窟," "寂寂三清宫," and "花落知多少." // The divisive campaigns that disrupted research at Mogao Grottoes during the Cultural Revolution are discussed by his former colleague Xiao Mo here: http://www.yuwenwei.net/readnews.asp?newsid=8496 // On May 24, 2013, Gao Ertai gave a talk to the Library of Congress in which he summarized his studies of transformation texts. The Chinese text of his talk is available here: https://www.chinesepen.org/blog/archives/22094

Victor Mair said,

July 13, 2023 @ 6:09 am

@Denis Mair:

Thanks for introducing us to Gao Ertai. I vaguely heard of him in the past, perhaps partly through you. From what I can quickly glean on the internet about him, he was a painter, calligrapher, writer, critic, and philosopher. He is said to have "published four collections of essays on beauty and freedom in Chinese".

It's good to know about Gao's work at Dunhuang, though, in that respect he seems to be more of an aesthetician and art historian than a literary scholar. Strictly and briefly speaking, Gao mixes up biànwén 變文 ("transformation texts") and jīngbiàn 經變 ("sutra / scripture transformations"). The former are popular, semi-vernacular narratives that are a type of storytelling with pictures which had a tremendous impact on the development of subsequent prosimetric fiction and drama, whereas the latter are paintings based upon Buddhist Hybrid Sinitic (basically Literary Sinitic / Classical Chinese) texts with a heavy overlay of Sanskritic syntax and lexical elements.

For extensive studies of biànwén 變文 ("transformation texts"), see:

Victor H. Mair, Tun-huang Popular Narratives (Cambridge [Cambridgeshire] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

Victor H. Mair, T'ang Transformation Texts: A Study of the Buddhist Contribution to the Rise of Vernacular Fiction and Drama in China (Cambridge, Mass.: Council on East Asian Studies Harvard University: Distributed by Harvard University Press, 1989).

Victor H. Mair, Painting and Performance : Chinese Picture Recitation and Its Indian Genesis (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1988).