Retraction Watch: Swamp Man Thing

« previous post | next post »

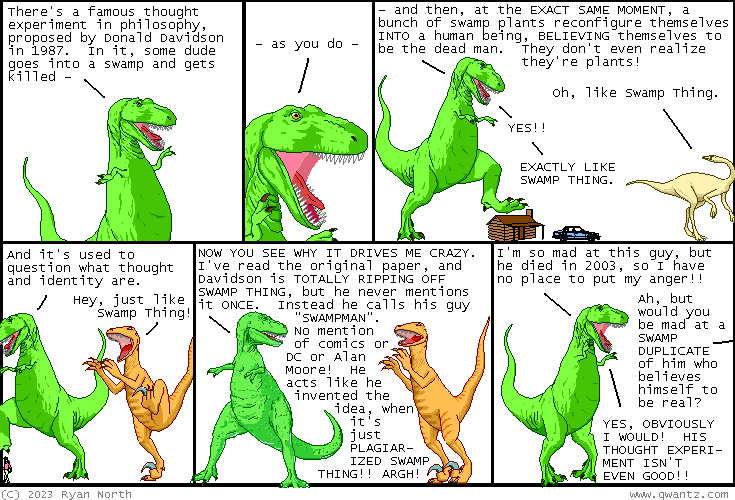

A recent Dinosaur Comic features a passionate investigation into alleged philosophical plagiarism:

The mouseover title: "For my next thought experiment, suppose a man, a super man, gets turned into energy and is widely considered to be the same man, but then one day splits into two energy guys: one red and one blue. WHICH IS THE REAL SUPER MAN? philosophy says: wow, we may never know."

Donald Davidson's contribution, as described in volume 3 of his collected essays:

'Knowing One's Own Mind', Essay 2, was delivered as the Presidential Address at the Sixtieth Annual Pacific Division Meeting of the American Philosophical Association in Los Angeles on March 28, 1986, and published in Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association (1987), 441-58.

Davidson's essay starts like this:

There is no secret about the nature of the evidence we use to decide what other people think: we observe their acts, read their letters, study their expressions, listen to their words, learn their histories, and note their relations to society. How we are able to assemble such material into a convincing picture of a mind is another matter; we know how to do it without necessarily knowing how we do it. Sometimes I learn what I believe in much the same way someone else does, by noticing what I say and do. There may be times when this is my only access to my own thoughts. According to Graham Wallas, 'The little girl had the making of a poet in her who, being told to be sure of her meaning before she spoke, said 'How can I know what I think till I see what I say?" A similar thought was expressed by Robert Motherwell: 'I would say that most good painters don't know what they think until they paint it.'

Gilbert Ryle was with the poet and the painter all the way in this matter; he stoutly maintained that we know our own minds in exactly the same way we know the minds of others, by observing what we say, do, and paint. Ryle was wrong. It is seldom the case that I need or appeal to evidence or observation in order to find out what I believe; normally I know what I think before I speak or act. Even when I have evidence, I seldom make use of it. I can be wrong about my own thoughts, and so the appeal to what can be publicly determined is not irrelevant. But the possibility that one may be mistaken about one's own thoughts cannot defeat the overriding presumption that a person knows what he or she believes; in general, the belief that one has a thought is enough to justify that belief.

Swampman comes along somewhat later:

But it was Hilary Putnam who pulled the plug. Consider Putnam's 1975 argument to show that meanings, as he put it, 'just ain't in the head'. Putnam argues persuasively that what words mean depends on more than 'what is in the head'. He tells a number of stories the moral of which is that aspects of the natural history of how someone learned the use of a word necessarily make a difference to what the word means. It seems to follow that two people might be in physically identical states, and yet mean different things by the same words.

[…]

Since some may be a little weary of Putnam's doppelganger on Twin Earth, let me tell my own science fiction story—if that is what it is. My story avoids some irrelevant difficulties in Putnam's story, though it introduces some new problems of its own. […] Suppose lightning strikes a dead tree in a swamp; I am standing nearby. My body is reduced to its elements, while entirely by coincidence (and out of different molecules) the tree is turned into my physical replica. My replica, Swampman, moves exactly as I did; according to its nature it departs the swamp, encounters and seems to recognize my friends, and appears to return their greetings in English. It moves into my house and seems to write articles on radical interpretation. No one can tell the difference.

But there is a difference. My replica can't recognize my friends; it can't recognize anything, since it never cognized anything in the first place. It can't know my friends' names (though of course it seems to); it can't remember my house. It can't mean what I do by the word 'house', for example, since the sound 'house' Swampman makes was not learned in a context that would give it the right meaning—or any meaning at all. Indeed, I don't see how my replica can be said to mean anything by the sounds it makes, nor to have any thoughts.

As for Swamp Thing, Wikipedia tells us that

As for Swamp Thing, Wikipedia tells us that

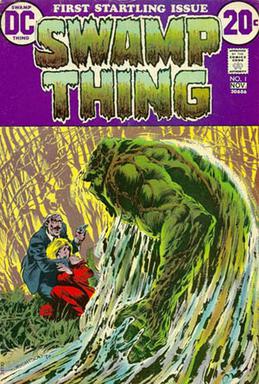

The Swamp Thing is a superhero in American comic books published by DC Comics. A humanoid/plant elemental creature, created by writer Len Wein and artist Bernie Wrightson, the Swamp Thing has had several humanoid or monster incarnations in various different storylines. The character first appeared in House of Secrets #92 (July 1971) in a stand-alone horror story set in the early 20th century. The character then returned in a solo series, set in the contemporary world and in the general DC continuity. The character is a swamp monster that resembles an anthropomorphic mound of vegetable matter, and fights to protect his swamp home, the environment in general, and humanity from various supernatural or terrorist threats.

The character found perhaps its greatest popularity during the original 1970s Wein/Wrightson run and in the mid-late 1980s during a highly acclaimed run under Alan Moore, Stephen Bissette, and John Totleben. Swamp Thing would also go on to become one of the staples of the Justice League Dark team of magical superheroes.

The character has been adapted from the comics into several forms of media, including feature films, television series, and video games. The character made its live-action debut in the film Swamp Thing (1982), with Dick Durock playing the Swamp Thing, while Ray Wise played Alec Holland.

So the date of the feature film is just about right to have inspired the thinking behind Davidson's 1986 essay.

But the story is somewhat different. For one thing, it's important to the philosophical parable that Swampman is an exact physical replica of Donald Davidson, whereas the DC Comics character is visually a monster:

|

|

And Swamp Thing's origin story (at least the first of several) involves death in a not-in-the-swamp explosion followed by swamp burial, not a lightning bolt striking a tree next to a living person in a swamp:

Alexander "Alex" Olsen was a talented young scientist in Louisiana in the early 1900s, married to Linda. Alex's assistant, Damian Ridge, was secretly in love with Linda and plotted the death of his friend. He tampered with Olsen's chemicals, killing him in the explosion, and dumped his body in the nearby swamp. Ridge used Linda's grief to convince her to marry him; however, Ridge was confronted by Alex Olsen, now a risen humanoid pile of vegetable matter. Olsen killed Ridge but Linda did not recognize him and ran away, leaving Olsen to wander the swamps alone as a monster.

But still…

Update: From John Baker in the comments, Wikipedia's List of Swamp Monsters… all of which, even if derived from human individuals, are visually far from exact copies. So Davidson's parable, even if inspired by popular culture, introduces a crucial new aspect. Sort of Swamp Thing meets the Body Snatchers…

John Baker said,

May 10, 2023 @ 7:05 pm

In reality, I think it is clear that Swampman derives from a long line of swamp monsters and was not necessarily influenced specifically by Swamp Thing. The original was It, by Theodore Sturgeon, and the first comic book character was the Heap. Wikipedia has a list at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_swamp_monsters.

Peter Hollo said,

May 10, 2023 @ 7:13 pm

It's also interesting that Davidson's Swampman is just another formulation of a philosophical zombie, which had most certainly been around for a while by the time this address was delivered in 1986 – although it was David Chalmers that really popularised them in 1996 in The Conscious Mind.

So, a second-hand story to descibe a second-hand thought experiment?

Well, philosophy is all about finding new ways to conceive of ideas.

Still, Davidson thinks it's obvious that Swamp-David isn't conscious. I'm with Ryan North – that's anything but obvious. I would prima facie think that a physical replica of me would have all my thoughts, but I'm innately disposed towards physicalism, so go figure.

The Wikipedia article on p-zombies has a decent history of the idea, as wel as the term "zombie" to describe them. Davidson's Swampman does make an appearance.

rm said,

May 10, 2023 @ 7:44 pm

For what it's worth, later Swamp Thing comics established that Swamp Thing is a sentient vegetable creature who learns tbat he was never Alex Olsen — he only thought he was. He is an ancient elemental creature who briefly had the delusion he was transformed from a man. That story is what the dinosaur says Davidson plagiarized.

chris said,

May 10, 2023 @ 8:14 pm

It seems clear to me that Swampman, as the scenario is presented, *does* know Davidson's friends' names, even though he never learned them, and he remembers Davidson's house even though he was never there.

I note that Davidson misgenders Swampman by any possible standard, despite having put the word "man" in the name himself; it was a long time ago and Swampman, being fictional, will neither object nor suffer any harm, but it's hard not to jump to the conclusion that Davidson did that *intentionally* to rhetorically emphasize the otherness of Swampman.

The fact that so many of Swampman's memories are *false* is due to his bizarre origin story. But unlike most people with false memories, that won't actually be a problem for him because he effortlessly impersonates Davidson and anyone who remembers Davidson being at some prior event won't contradict Swampman's claim to have been there.

I don't think any of this actually has all that much to do with Swamp Thing, which is AFAIK instead more about how Swamp Thing *appears different* from his previous lifetime and how that screws up all his relationships. Either the dinosaurs or their creator were just confused by both having "swamp" in the names, I guess?

David L said,

May 10, 2023 @ 8:30 pm

I would prima facie think that a physical replica of me would have all my thoughts

I disagree. My take is that a person's thoughts and memories are dynamic in nature, consisting of the chemical and electrical signals that rattle around in the brain. I don't believe our memories are permanent, as if they were fixed states on a hard drive, for example.

So when the original person is destroyed, all his thoughts and memories vanish. The replica that emerges from the swamp might have his physical structure, but it would be loaded with the correct software and operating system, so to speak.

David L said,

May 10, 2023 @ 8:31 pm

would NOT be loaded, I meant to say…

Brett said,

May 11, 2023 @ 12:22 am

I suspect that Davidson's use of the name "swampman" is a reference to the fact that there were two very similar comic book characters created in 1971, Swamp Thing and Man-Thing, with fairly similar origins. Both of them (in their original formulations—before Moore retconned Swamp Thing into a mere imitation of Alex Olsen) were brilliant scientists whose dead bodies ended up lost in the swamps of the American South. The combined effects of swamp magic and the advanced biochemical agents they had been working on (and been exposed to) caused the them to be reconstituted as shambling human-vegetable hybrids, who went on to wreak revenge on the villains responsible for their deaths.

These similarities are not coincidental. In 1971, Gerry Conway, one of the creators of Man-Thing for Marvel, and Len Wein, one of the creators of Swamp Thing for D. C., were roommates. Moreover, over the next few years, both of them actually ended up working on both comics.

Peter Grubtal said,

May 11, 2023 @ 6:28 am

@John Baker, David L

Good that Heap is not forgot, although I only came across him in a take-off in MAD magazine. In the….sixties?

On the question which is exercising the philosophers, surely David L said it: I don't understand how there can be anything more to discuss.

It calls to mind the old anecdote…terrible noise coming from the office of the Dean of the college, he's ranting at the head of the physics faculty who wants a new particle accelerator: the Dean: "100 million for your toy, always you **** physicists bankrupting this college – why can't you be like the English faculty, they just need paper, pencils and a wastepaper basket….or like philosophy even, they just need paper and pencils".

KeithB said,

May 11, 2023 @ 7:10 am

I am confused by this:

"It can't know my friends' names (though of course it seems to)"

That seems to imply that the memory is there, but it can't "know" them because it is a replica.

Mark P said,

May 11, 2023 @ 8:48 am

I think the idea that the physically-identical replica can’t “know”’what the original knows assumes that the original’s knowledge and thoughts come from something not contained in the physical structure of the body. Exactly what and where that would be, I do not know.

David L said,

May 11, 2023 @ 8:58 am

On further reflection, I think the problem with the original idea is inexactness about what is meant by a 'physical replica.' If it means something that is truly identical to the original person, down to every last quantum state of every electron in every atom in every molecule of the original, then it would be indistinguishable in any way and would perforce contain all the thoughts and memories of the dead person. It would be the same person, in fact.

But there are also these crazy people with too much money who plan on having their bodies or just their brains put into deep freeze as soon as they die. They are wasting the money, because the cryo-stiffs would not preserve the dynamics aspects of their brain function etc that I mentioned before. A better idea, as I think Ray Kurzweil has suggested, would be to upload your brain contents into a digital repository so that they could be later downloaded into a robot. It might not look like you but it would be you, intellectually and psychologically.

bks said,

May 11, 2023 @ 10:23 am

Upload brain contents into a digital repository? Can that be done at different ages? Can we download 2-month-old Ray Kurzweil into one robot and 60-year-old Ray Kurzweil into another?

David L said,

May 11, 2023 @ 10:39 am

The technology doesn't yet exist, of course, and the answer to your question would depend on whether the uploading process is non-destructive or not…

Gregory Kusnick said,

May 11, 2023 @ 11:06 am

David L:

I think the evidence is against your model of memory. We awaken from general anaesthesia or concussion with our long-term memories intact, which strongly suggests that they're encoded in the physical structure of the brain (connections between neurons) and not in some volatile electrochemical state. This is supported by observations that electrical stimulation of specific neurons can elicit highly specific memories.

To my mind the problem with Davidson's thought experiment is that the simultaneous destruction of one brain and the creation of an exact replica of it seems to imply a causal connection between the two, despite Davidson's disclaimer that it's "entirely by coincidence".

A better formulation might be to imagine that sometime in the inconceivably remote future, long after the heat death of the universe, a random collocation of gas molecules happens to coalesce into a Boltzmann brain that (by even more absurd coincidence) happens to be an exact replica of my brain right now. It seems pretty clear that anything that brain thinks it knows is an illusion with no basis in history, and indeed for each such brain that exactly replicates my memories, there are inconceivably many inexact replicas that "know" things that were never true of me here in the present.

Brett said,

May 11, 2023 @ 12:07 pm

@Mark P: That "knowledge… come[s] from something not contained in the physical structure of the body" was precisely what Hilary Putnam was arguing, although not in the way you seem to mean. Putnam argued that a lot of what we think we "know' is really knowledge if it corresponds correctly to something in the external physical world. For example, Putnam described a first encounter with intelligent aliens who appear to speak English, but with tiny differences. For examples, when the aliens say "aluminum" they really mean what we would call molybdenum. Despite both sides in the conversation (human and alien) having a perfectly clear understanding of what they are themselves talking about, they are taking past each other, and if they actually have to work with some "aluminum," the facticity of its chemical makeup will suddenly matter. Hence, Putnam argued, real meaning cannot just be in the mind.

David L said,

May 11, 2023 @ 12:14 pm

Neuroscience is not at all my area of expertise, but during general anesthesia or concussion the brain is still active — it does not switch off entirely so presumably retains some electrochemical activity. I'll accept that there can be some physical basis for memory but in any case the point stands that unless you can reproduce not only the physical structure of the brain but also its dynamic activity then you cannot reproduce the whole person.

I agree with your point about the dubious coincidence in the thought experiment.

Whether the memories of the Boltzmann brain you posit are illusions gets into deep waters, I think. One could argue that they would be genuine memories of real events, just not events experienced by the brain in question. But maybe that's semantics.

Gregory Kusnick said,

May 11, 2023 @ 1:22 pm

If I roll a handful of dice repeatedly, and one of those rolls happens to reproduce my phone number, I think it would be difficult to argue that that one roll, as distinct from all the others, somehow embodies genuine knowledge of a true fact about the world. There needs to be some causal relation between the fact and its representation for the latter to count as genuine knowledge.

KeithB said,

May 11, 2023 @ 3:36 pm

David L:

Much like the Star Trek TNG episode "Darmok" where they came across an alien species that spoke entirely in metaphor. The words could be translated into English, but made no sense unless you understood the referent.

Terry Hunt said,

May 11, 2023 @ 5:30 pm

It seems to me that Davidson's description of his hypothetical 'Swampman' is impossible and self-contradictory. I might go so far as to describe it as a strawman.

Peter Grubtal said,

May 12, 2023 @ 4:19 am

The Swampman scenario seems to be just a recontextualisation of Last Thursdayism.

And what is implied by "genuine knowledge", "true facts" smacks to me of scholasticism or Platonic ideals.

Scott P. said,

May 12, 2023 @ 7:08 pm

And what is implied by "genuine knowledge", "true facts" smacks to me of scholasticism or Platonic ideals.

It's not clear if you consider that a good thing or a bad thing.

There is some connection to the question of whether a number such as pi is 'normal' — that is, does every number, and every number sequence, appear with the same frequency? If so, since pi is infinite, every finite sequence will appear, indeed, an infinite number of times, in its decimal expansion.

If it is normal (which mathematicians suspect, but cannot yet prove), then if you converted the digits of pi into the letters of the English alphabet, the complete works of Shakespeare would appear, uninterrupted, somewhere within the number. So would the works of Milton, or Proust. Of course, there would also be an exact copy of Shakespeare with the exception of one line that reads "Out, out damned spout." copies with many lines changed, copies that are only tiny fractions of Shakespeare, etc.

David Marjanović said,

May 13, 2023 @ 9:54 am

I was taught twenty years ago that the formation of long-term memories involves the growth of extra synapses between the neurons involved. This is preceded by other things like stabilization of neurotransmitter production at the existing synapses, various phosphorylation phenomena etc. etc., all of them reversible.

The most interesting thing about anesthesia, to me, is that I wake up from it with no sense that time has passed (let alone how much) since I lost consciousness. This is very different from sleep.

db said,

May 15, 2023 @ 9:52 pm

@Scott P: I think you're mixing up quite a few mathematical concepts. Just because the decimal expansion of pi is infinite, does not mean that it contains all possible combinations of all possible values. Neither it being irrational, nor it being normal (if proven) would be sufficient for that. For example, it's trivial to prove that it cannot contain a repeating, rational number.

@Davlid L: "upload your brain contents into a digital repository" is just as bollocks as freezing your brain. At the very least, it's so woefully ill-defined as to be completely meaningless. What is meant by "brain contents"? How would those brain contents be digitized? Without any of those answers, it's the exact same premise as freezing your brain. Both are just a very abstract concept of "preserve the meaningful state" without any understanding of what the meaningful state that needs to be preserved is. Without that foundation, it's just pure sci-fi nonsense.

unekdoud said,

May 21, 2023 @ 1:57 am

The whole concept of perfectly copying and interpreting a brain is a bit too much into sci-fi for me, so what about something out of this decade? Let me introduce Chatman, a generative AI that has read all my writing and can impersonate it perfectly. Nobody, human or computer, can tell the difference.

Let me also introduce (as a strawman) the argument that nothing that Chatman says while impersonating me has any meaning, as it learns all its language in a different context from me. (A more traditional opinion is that Chatman is nothing more than math and numbers. Feel free to differ.)

(Some mixing up of experiments ahead.)

1. I write an essay of 1000 words, then all the even-numbered words are deleted and Chatman fills them back in as best as it can.

Has meaning been destroyed and then restored, or was it permanently gone with the deletion? Does the final text have a different meaning? Does it depend on whether Chatman got an exact reconstruction?

2. I'm trapped in a sealed box with Chatman, and we each write a 1000-word passage. At the end of the hour, one of the texts is output by the box, but its origin is not revealed.

Does the output text have meaning? Does the answer change in retrospect if the origin is revealed?

3. Scientists have designed a button that will destroy exactly one of us in the sealed box, at random. As we're isolated beforehand, the survivor does not get to witness this. The survivor is then allowed to exchange messages with the outside world, but not reveal their identity.

Do these messages have meaning? Does the answer change if the button is faulty and nobody dies? Does any of the above change if eventually the whole box is destroyed and nobody can ever know who wrote which message?