The Twittering Machine

« previous post | next post »

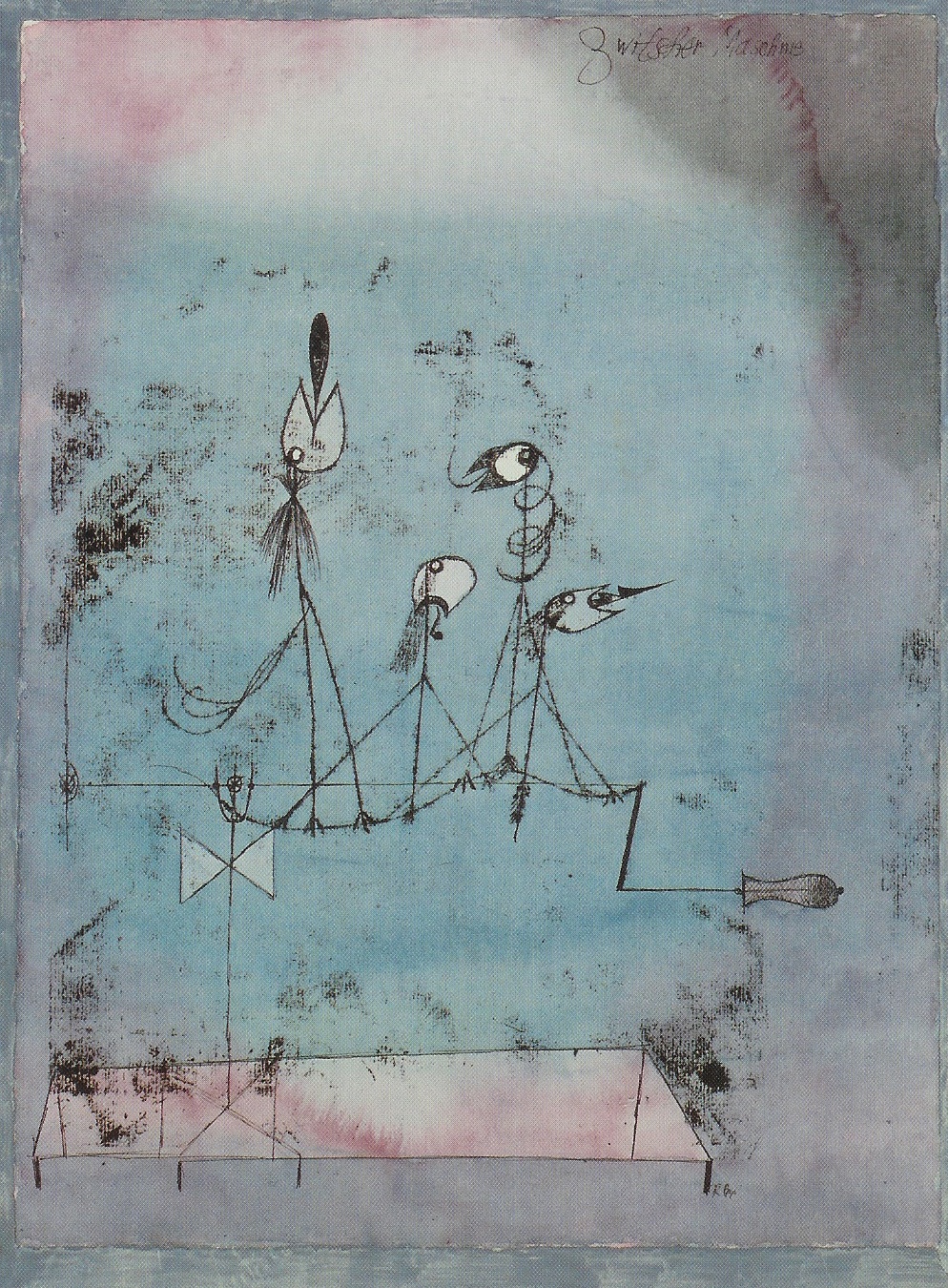

Illustrating Ben Tarnoff's 11/11/2022 NY Review of Books article "In the Hothouse", Paul Klee's 1922 painting Die Zwitscher-Maschine ("The Twittering Machine"):

Wikimedia's English description: "Group of birds shackled to a wire attached to a hand crank."

The start of Tarnoff's article:

Mark Zuckerberg once called Twitter a clown car that fell into a gold mine. Now there is a new clown behind the wheel, and the gold’s all gone. Twitter has long been bad at making money, clownishly bad. But it continued to attract investment, thanks to the low interest rates engineered by the Federal Reserve to ease the pain of the 2008 global financial crisis and its long aftermath. Gorged with capital, investors spent many years pouring money into tech firms that don’t make money in the belief that someday they would.

In today’s macroeconomic environment, the appetite for such risks has subsided. The worst inflation since the early 1980s has got the Fed rapidly cranking up rates. The financial floodplains of Silicon Valley are drying up; it is a time of layoffs, hiring freezes, down rounds, and cratering stock prices. It is therefore the worst possible moment in recent memory to acquire an unprofitable tech company, especially if you paid a high price for it and took on a lot of debt to do so.

A mine with nothing left to mine is just a hole in the ground. And this is where Elon Musk now finds himself: deep in a hole. The precise depth of the hole was determined by a gag. Back in April, when he made his first bid, he proposed to take Twitter private at $54.20 a share, a weed reference, and that is ultimately what he paid. This stupid number is more meaningful than it may seem. It reveals a wider truth, one that does not displace so much as subsume the various interpretations about why Musk is behaving the way he is: it’s all a joke.

A joke is a terribly serious thing. It makes matters more complicated rather than less. Freud said that jokes are like dreams: they come from the unconscious, he believed, and are thus glutted with meanings in excess of those intended by the teller. Musk’s relationship to Twitter is, to use a Freudian word, overdetermined. It is a bundle of psychic attachments so densely knotted that it would take a century on the couch to unravel.

For Musk, Twitter means too much. It is an outlet for his immeasurable ressentiment, an incubator for his reactionary politics, an arena for irony-poisoned meme combat, a stage from which to cultivate a fanbase, a megaphone for marketing his various ventures, a place to get his feelings hurt, a high school cafeteria full of cool kids against whom to take revenge. And this is what makes him such a lousy chief executive. The cool discipline of capital requires restraint. Musk, by contrast, has spent his short tenure as Twitter’s owner in a fever of desublimation—antagonizing the advertisers on whom the vast majority of Twitter’s revenue depends, haggling with Stephen King over the price of a blue check, circulating a right-wing conspiracy theory about the attack on Nancy Pelosi’s husband, laying off half of Twitter’s employees only to ask some of them to take their jobs back the next day.

One gets the sense that Musk, despite having turned Twitter into a personal dictatorship, is not exactly in control. Oedipus was king of Thebes and also, famously, not exactly in control. There is something poignantly Greek about the likelihood that Twitter may die, or at least be mangled beyond recognition, at the hands of someone who can’t seem to live without it. It would be a fitting end for the most neurotic website on the Internet.

Perhaps because of the current chaos, Twitter seems more interesting than ever. I personally hope that something non-toxic emerges, though at the moment it's hard to see how.

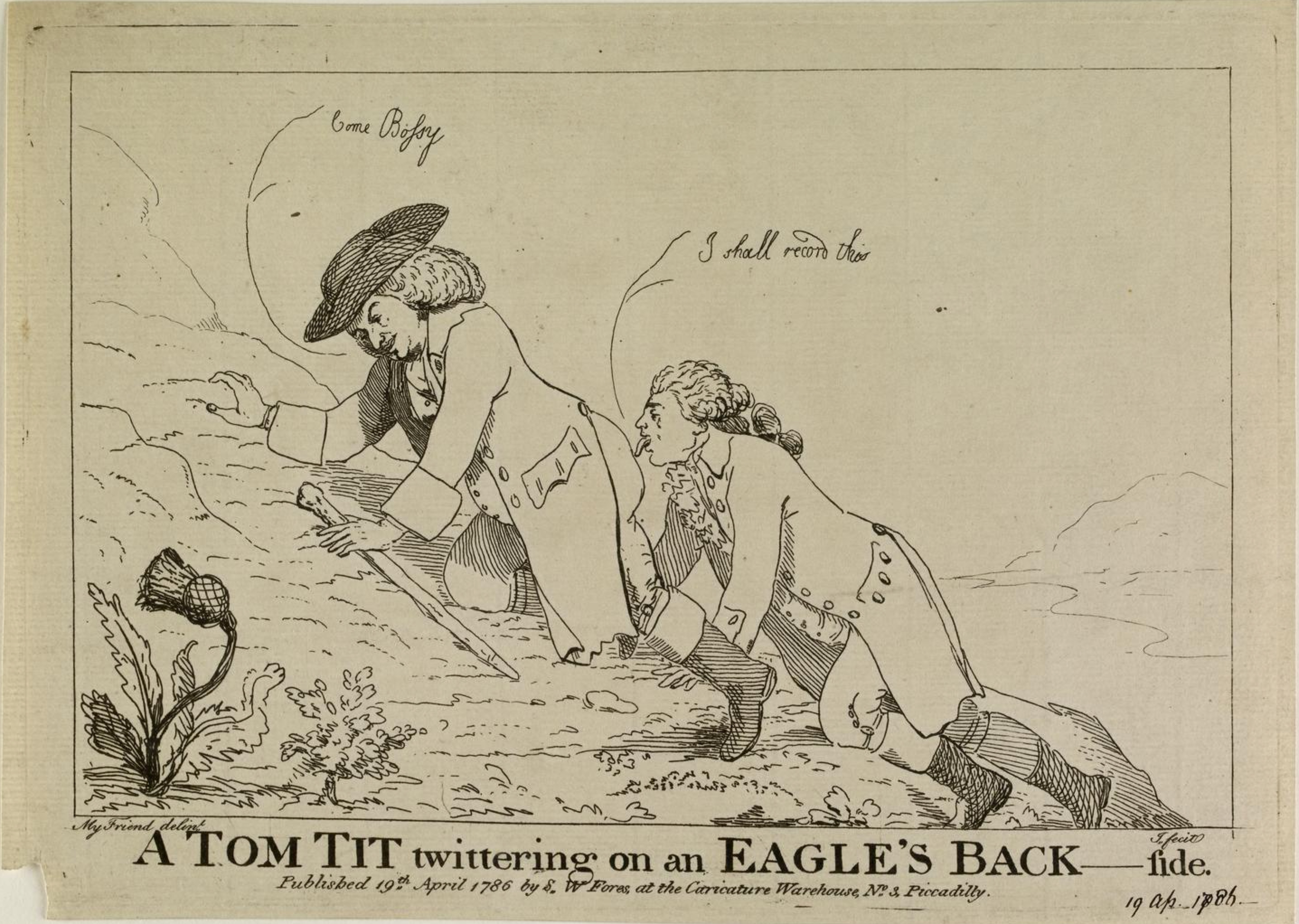

Amplifying the Freudian resonance, Wikimedia's other hit for "twittering" is a satirical 1786 etching A Tom Tit twittering on an eagle's back-side:

Wikimedia's description:

Johnson (left) climbs up a mountain on hands and knees, his oak stick in his left hand. Boswell follows, also on hands and knees; he licks Johnson's posteriors, saying, "I shall record this". Johnson says, "Come Bossy". Behind and below them a loch and mountain (right) are indicated. In the foreground (left) is a huge thistle.

Presumably this is a blend of two of the OED's senses for the noun twittering:

2.a. An eager desire or longing; a hankering, a yearning. Frequently with prepositional phrase or infinitive expressing the object of desire.

2.b. The action or an instance of trembling, shaking, or quivering.

I suppose that in modern times, Boswell would again be twittering, though the meaning has continued to evolve.

Philip Taylor said,

November 13, 2022 @ 10:33 am

I can't see any visible evidence of the birds being shackled to the wire — to my eye, they merely appear to be perching on it.

Mark Liberman said,

November 13, 2022 @ 12:12 pm

The page for this work at MOMA says:

A violent marriage of nature and industry, the crazy contraption in Twittering Machine mechanizes the songs of birds. All but one bird are tethered to a perch that can be turned by a handle over a pit, a potential trap for the latest choir member. Constructed with Klee’s characteristic wiry, agile black line, the birds lurch and cry out, their tongues resembling both musical notes and fishhooks. Klee described drawing as “an active line on a walk, moving freely” and connected his liberated line to his belief that “through the universe, movement is the rule.” In this drawing, humans turn movement and song against nature, making them activities of enslavement.

And the Wikipedia article says

The picture depicts a group of birds, largely line drawings; all save the first are shackled on a wire

But in any case, the shackling-or-not issue is probably the least relevant aspect of the post…

Philip Anderson said,

November 13, 2022 @ 2:19 pm

@Philip Taylor

Looking closely, the three birds on the right appear to have three legs each, some of which clearly end in birds’ feet, but the middle ones end in more of a ball, so those are probably chains.

Bob Ladd said,

November 13, 2022 @ 2:20 pm

This post reminded me of Neil Smith's book The Twitter Machine (subtitle "Reflections on Language"), which came out long before Twitter got started. I always wondered about the title, and now I wonder if the book (which I haven't read) makes reference to Klee's painting. And whether Twitter was inspired by either of them.

Stephen Hart said,

November 13, 2022 @ 3:00 pm

There's also The Twittering Machine, 2019, Richard Seymour

Here's the beginning of the Amazon description:

In surrealist artist Paul Klee’s The Twittering Machine, the bird-song of a diabolical machine acts as bait to lure humankind into a pit of damnation. Leading political writer and broadcaster Richard Seymour, author of Corbyn: The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics, argues that this is a chilling metaphor for our relationship with social media.

https://www.amazon.com/Twittering-Machine-Richard-Seymour/dp/1999683382

Bloix said,

November 13, 2022 @ 3:03 pm

The birds are not "tethered" or "shackled" as living birds would be; they are attached, as part of the mechanism. The tweets they make are as artificial as they are.

You can see an example of the kind of object the Twittering Machine would be in this video of Caulder's Circus, which was contemporaneous with the Klee drawing, starting at about 1:55 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GS2q-8dFyiw

And here is an attempt to construct the Twittering Machine itself

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tMdsPD1adP4

Philip Taylor said,

November 13, 2022 @ 5:05 pm

Philip Anderson — you are, of course, quite correct. I failed to count the bird's legs, and at least three of them have more than the canonical two. It is interesting that even when one clicks to "embiggen" (is that a real word ?), the image is still displayed at far less than full resolution — for example, Paul Klee's painting is displayed at 556px × 755px, whereas the underlying image is actually 994px × 1,350px.

Lucas Christopoulos said,

November 13, 2022 @ 5:58 pm

Les Shadoks:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Les_Shadoks

Seth said,

November 13, 2022 @ 6:30 pm

I wish that "Tom Tit" cartoon had a description explaining the context and intended message. It's clearly some sort of insulting commentary on the parties involved. But the past is another country.

Still, the forms may change, but the content does not.

Brett said,

November 13, 2022 @ 10:59 pm

@Seth: It's James Boswell licking Samuel Johnson's butt. The presumable implication was that Johnson (the eagle) was the important figure, while his friend and (later) biographer Boswell was a mindless little twittering tit—who recorded and transmitted whatever Johnson happened to say, whether it was actually important or not.

(The puzzling bit, to me, is the fact that the cartoon is dated 1786. That puts it in between Johnson's death in 1784 and the publication of Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson in 1791. I would have imagined that the strain of critique seen in the cartoon would not have been particularly salient in the intervening years. However, it may be an indication that Boswell had been heavily promoting his writing about Johnson for years before the final publication of his biography.)

Peter Grubtal said,

November 14, 2022 @ 3:16 am

@Brett

Boswell's " A Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides" was published in 1785 (cf. the thistle in the cartoon), and presumably there was some puff going on for that book, which provoked the satire.

This part of the past is not so foreign, being heavily documented.

Seth said,

November 14, 2022 @ 7:46 am

@Brett Thanks. I absolutely could see this being on social media today, with the relevant style updates :-)

Neil Smith said,

November 15, 2022 @ 6:39 am

The title of my book The Twitter Machine, as well as the choice of the picture on its cover, were determined by my admiratioon for Klee's work and my frustration as Head of Linguistics at UCL at not having time to do the major concentrated work I had hoped for. So I chose titles of a variety of Klee's pictures which inspired me to write essays on miscellaneous topics in linguistics, while simultaneously showing my delight at Klee's whimsical humour.

There were other motivations: I had long wanted something to dedicate to my sons; a means of drawing attention to, and perhaps alleviating, the grim position of my friend Jack Mapanje, imprisoned in Malawi by the egregious Hastings Banda; a way to share my conviction that linguistics is primarily fun. And writing books takes too long.

Nathan said,

November 15, 2022 @ 11:13 am

@Philip Taylor: Embiggen is a perfectly cromulent word.

Philip Taylor said,

November 15, 2022 @ 12:53 pm

"Embiggen is a perfectly cromulent word" — patterned on "GNU is Not Unix", "PIP Installs Packages", "TikZ ist kein Zeichenprogramm" and so on, I assume …

Ellie Kesselman said,

November 15, 2022 @ 3:17 pm

Philip Taylor: Um close but not quite. Embiggen has a web-conscious, neologism-type meaning as well as an historical one. The etymology of cromulent is another story entirely. See here for more https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisa_the_Iconoclast#Embiggen_and_cromulent

Neil Smith: Yes, Paul Klee's work does show his whimsical humor! The phrase about your imprisoned friend made me feel sad, and evoked thoughts of Klee's Angelus Novus.

Philip Taylor and Philip Anderson: The angel of Angelus Novus (1920) has somewhat similar feet to the birds of the Twittering Machine (1922). The angel has three toes but only two legs though.