Free Tibet!/?

« previous post | next post »

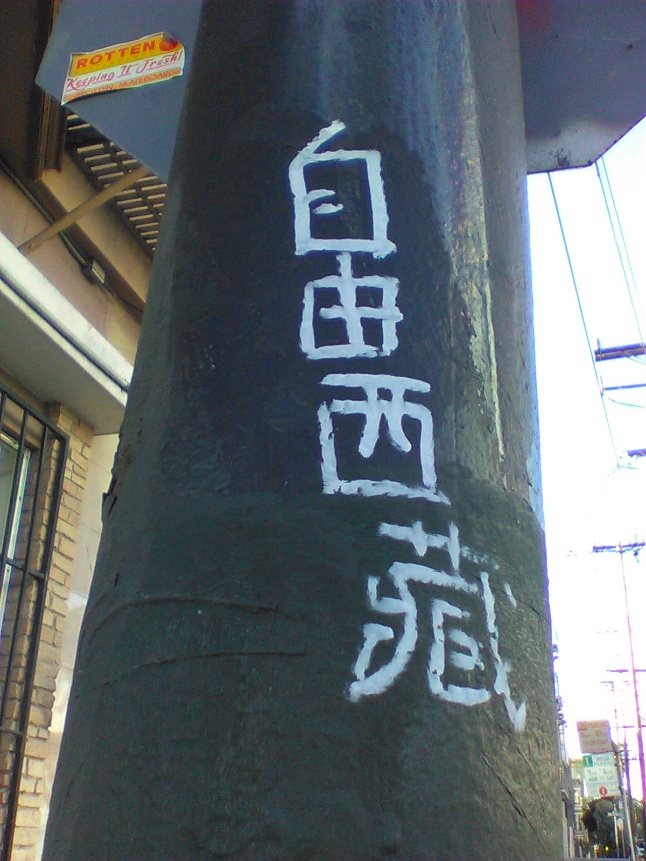

From Charles Belov: seen on a street-sign pole in the Mission District of San Francisco:

The writing says:

zìyóu Xīzàng 自由西藏 ("free Tibet")

Seems pretty straightforward, doesn't it? Not to me, though. As soon as I read it, my grammar antennae went up. The way it's stated just doesn't sound like authentic Chinese. It grates against my ears as unidiomatic. Why?

First, although (according to some native speakers) it's apparently possible to force "zìyóu 自由" ("free[dom]; liberty") to function as an imperative verb when followed by a noun like Tibet (though that really seems odd, if not impossible, to me), it is far more common to think of it as an adjective / modifier. If one really does want to make an imperative call to "free Tibet!", the verb one would use is "jiěfàng 解放" ("liberate"). But "jiěfàng Xīzàng 解放西藏" ("free Tibet") still does not ring true in this context, since it has been coopted by Marxist-Leninist rhetoric, whereas Tibet is currently a part of the People's Republic of China, which is a communist country dominated by Marxist-Leninist ideology, while the person responsible for the writing on the street sign pole in the Mission District of San Francisco almost certainly is calling for Tibet to be freed from communist control.

I felt fairly confident about my reflections on the idiomaticity of the writing on the pole, but wanted to check my assessment with native speakers. Here are responses from three humanities PhD candidates who are native speakers of Mandarin:

I.

I think you have the right instinct that jiěfàng 解放 sounds more natural when "free" is a verb, and that zìyóu Xīzàng 自由西藏 can be construed both ways just as Free Tibet in English. While it is very likely that this phrase is meant to be ambiguous (is there a significant difference?), I tend to think that it is in the former sense as it is not yet free. Zìyóu xīzàng 自由西藏 with zìyóu 自由 as an adjective sounds okay to me. For a slogan like this, some elements have to be truncated.

If one were to overinterpret it, jiěfàng 解放 seems semantically slimmer, whereas zìyóu 自由, in addition to the two senses you mentioned, can mean a natural state of being ever since its inception.

II.

Theoretically, both jiefang and ziyou work in this case, so one might call it a double entendre. However, practically, zìyóu 自由 works better in this scenario than jiěfàng 解放. First, jiěfàng 解放 is “liberate”. Second, it (either ‘jiefang’ in the Chinese case or ‘liberation’ in the international realm) has a very special association with the communist agenda — e.g., “jiěfàngqū 解放区” ("liberated area[s]), “jiěfàng quán Zhōngguó 解放全中国” ("liberate the whole of Chnia"), “gōngrén jiěfàng 工人解放” ("worker liberation"), etc, — which clearly this free-Tibet-supporter would like to get away from. And by contrast, zìyóu 自由 / freedom as an ideology and a concept, is nevertheless tied to the libertarian intellectual history / political agenda. Therefore, between the two key concepts of these contending political forces, the libertarian / anti-communist free-Tibet movement should utilize zìyóu 自由 in their political language.

III.

I believe you are completely right! I think "zìyóu Xīzàng 自由西藏" is mistranslated from the English translation of "jiěfàng Xīzàng 解放西藏" (free Tibet), since "zìyóu Xīzàng 自由西藏" doesn't make much sense (unless it refers to "Tibet as a place of freedom", which seems to be quite opposite to the translator's original meaning). As you suggested, "zìyóu 自由" here seems to be an adjective, and "zìyóu 自由" itself could be an adjective, an adverb, a noun, but never a verb.

All things considered, what sort of person would have been likely to write this kind of Chinese in such circumstances? My own judgement, checked against the opinion of the authors of I. II., and III. above, is that it is highly unlikely to have been a native speaker from any part of the Sinosphere. They just couldn't bring themselves to write that sort of awkward Chinese. Rather, it must have been a foreigner (or foreign-born Chinese with non-native ability in the language) who had middling or somewhat better command of the language. This interpretation is corroborated by the quality of the calligraphy.

Selected readings

- "Easy Grammar from the Free Hong Kong Center" (8/25/20)

- "Hong Kong protests: 'recover' or 'liberate'" (11/3/19)

Joe said,

August 9, 2022 @ 9:16 am

Lots of interesting comments about "free", but what about "Tibet"? I'm told by a native speaker that this message would be better translated as "free Xizang", where Xizang is the name that the Chinese government imposed on the region (cf. "Xinjiang" for East Turkestan). He says Mandarin-speaking Tibetans living free in Taiwan would never call their homeland Xizang, but rather Tibet 圖博.

Joe said,

August 9, 2022 @ 9:28 am

Oh and tying it all together, I'm told that 解放西藏 "jiěfàng Xīzàng" would therefore sound like a kind of sick Orwellian parody: it would be calling for the "liberation" of Xizang Province (not Tibet) into the greater Chinese workers' commune, i.e. calling for what has already happened.

Michael Watts said,

August 9, 2022 @ 12:17 pm

It is possible to interpret the English slogan "Free Tibet" as a statement of the goal rather than a command, the same way you'd interpret e.g. "Medicare for all". That reading would make 自由西藏 a more natural translation.

JOHN S ROHSENOW said,

August 9, 2022 @ 12:43 pm

I dimly recall a short-lived? publication in Taiwan in the late 1950s entitled Ziyou Zhongguo, which was translated, and understood, as "Free China", where 'free' was taken as an adjective.

PeterL said,

August 9, 2022 @ 2:56 pm

I had always parsed "Free Tibet" with "free" as an adjective. Similar to "Vive le Québec libre!" (Long live free Quebec! – which got de Gaulle in trouble in Canada in 1967. Similar parsing: Free France (French: France Libre) during WW2.

With that interpretation, wouldn't 自由 (adjective) make sense? Possibly 自由 is one of the 19th century Japanese neologisms that were adopted by Chinese https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E8%87%AA%E7%94%B1#Etymology_2

Chas Belov said,

August 9, 2022 @ 10:31 pm

Thank you for this insight.

Victor Mair said,

August 9, 2022 @ 10:47 pm

From a fourth PRC humanities PhD candidate who lives in California:

I don't think "zìyóu 自由" in Chinese can be a verb, as "free". I really can't think of any usage of this. According to my experience, many of those who write these kinds of signs in America actually do not have a good command of Mandarin. Sometimes I see similar signs at other places in California, and they just do not make much sense to me as well.

Victor Mair said,

August 9, 2022 @ 10:55 pm

From South Coblin:

I wonder if what native speakers of Chinese would most likely say in a case wouldn’t just be Xīzàng dúlì 西藏獨立 ("Tibet independence"). Compare Tâi-oân to̍k-li̍p 台灣獨立, which is a common slogan among Taiwan nationalists the world over.

Victor Mair said,

August 10, 2022 @ 8:16 am

So, South, your Xīzàng dúlì 西藏獨立 ("Tibet independence") and Tâi-oân to̍k-li̍p 台灣獨立 are noun phrases, not calls for action, right?

Victor Mair said,

August 10, 2022 @ 8:26 am

South's reply:

Right. The Taiwan one is often shortened to 台獨*, as in the verb phrase 鬧台獨**.

VHM: *Taiwan independence **agitate for Taiwan independence