Trends in book titles

« previous post | next post »

I've been interested for some time in the way that (written) English sentence lengths have evolved over time — see "Trends", 3/27/2022, or the slides from my 5/20/2022 talk at SHEL12, "Historical trends in English sentence length and syntactic complexity". It's well known that the titles of published books have undergone an analogous process, but I don't think I've written about it. (Nor do I know of any scholarship on the topic — perhaps some commenters will be able to suggest some.)

A couple of days ago, while looking for the origins of an idiom, I stumbled across a contender for the title-length championship in in an interesting work from 1740 (image here):

THE ART of READING: OR, THE ENGLISH TONGUE MADE Familiar and easy to the meanest Capacity. CONTAINING, I. All the common words, ranged into distinct tables and classes; as well in regard to the number of letters in each word, as to the easiness of pronunciation, and the bearing of the accent. With useful notes and remarks upon the various sounds of the letters occasionally inserted in the margin. II. A large number of lessons, regularly suited to each table. III. An explanation of several words; particularly such as are of the same, or nearly alike in sound: designed to correct and prevent some orthographical errors and mistakes. IV. Some observations, rules, and directions, relating to the reading and writing English properly and correctly. The whole done after a new and easy Method. Approved of, and recommended, as the best book for the use of children, and all others, who would speedily attain to the knowledge of the English tongue. By P. SPROSON, S. M.

Just as in transcriptions of spontaneous speech, it's not at all clear where "sentences" begin and end. Here periods are used to divide the title page into eight or nine segments:

THE ART of READING: OR, THE ENGLISH TONGUE MADE Familiar and easy to the meanest Capacity.

CONTAINING, I. All the common words, ranged into distinct tables and classes; as well in regard to the number of letters in each word, as to the easiness of pronunciation, and the bearing of the accent.

With useful notes and remarks upon the various sounds of the letters occasionally inserted in the margin.

II. A large number of lessons, regularly suited to each table.

III. An explanation of several words; particularly such as are of the same, or nearly alike in sound: designed to correct and prevent some orthographical errors and mistakes.

IV. Some observations, rules, and directions, relating to the reading and writing English properly and correctly.

The whole done after a new and easy Method.

Approved of, and recommended, as the best book for the use of children, and all others, who would speedily attain to the knowledge of the English tongue.

By P. SPROSON, S. M.

The whole thing is arguably a single noun phrase, with clear syntactic relationships among its parts. But it could also be considered a series of fragments, connected only by a rhetorical structure — if we believe that there's a bright line between syntax and rhetoric…

(I'll note passing that I've left off the two pseudo-quotations from Cicero, and the information about who published it when and for whom, which actually have a similar relationship to the preceding array of fragments.)

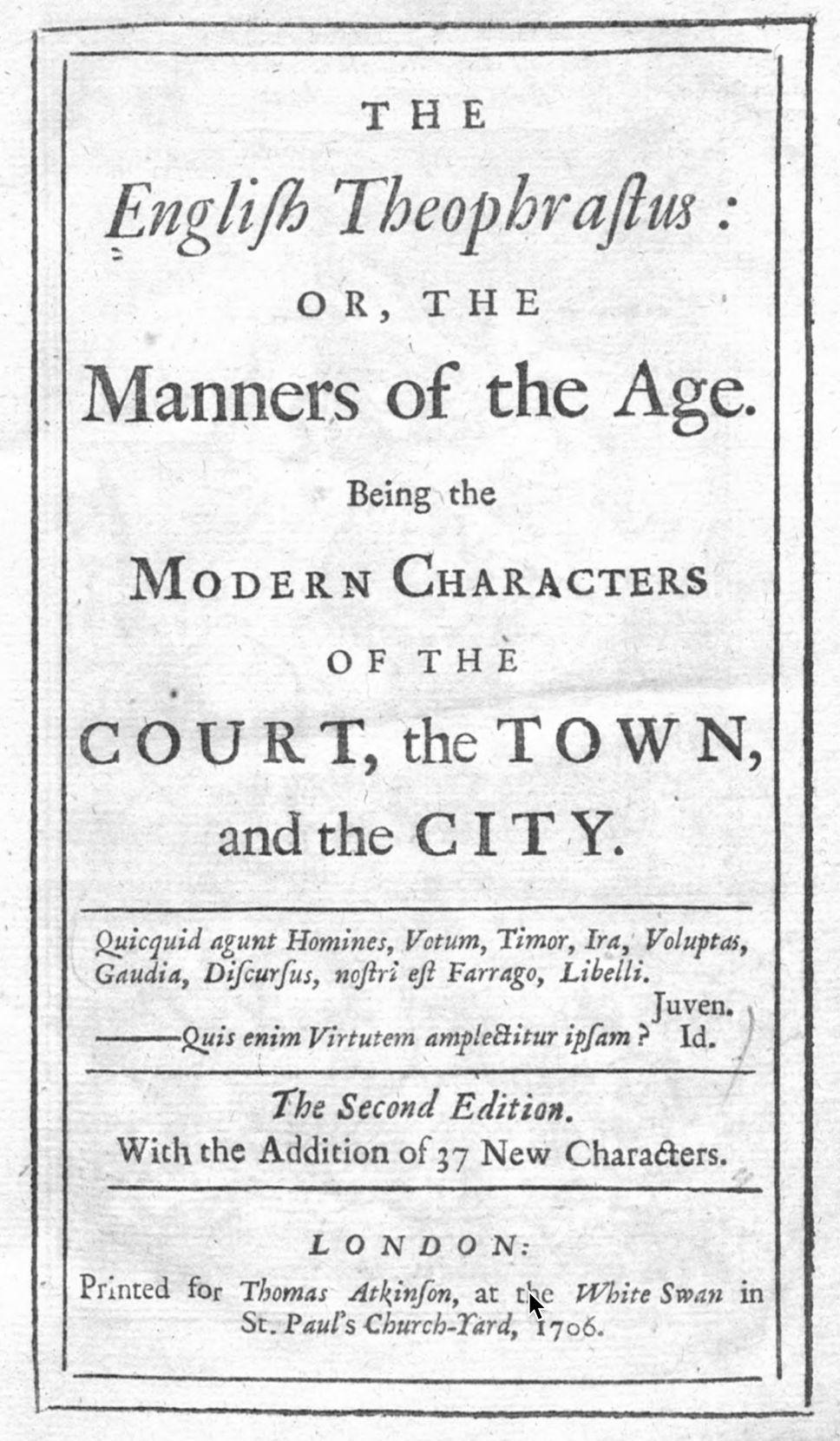

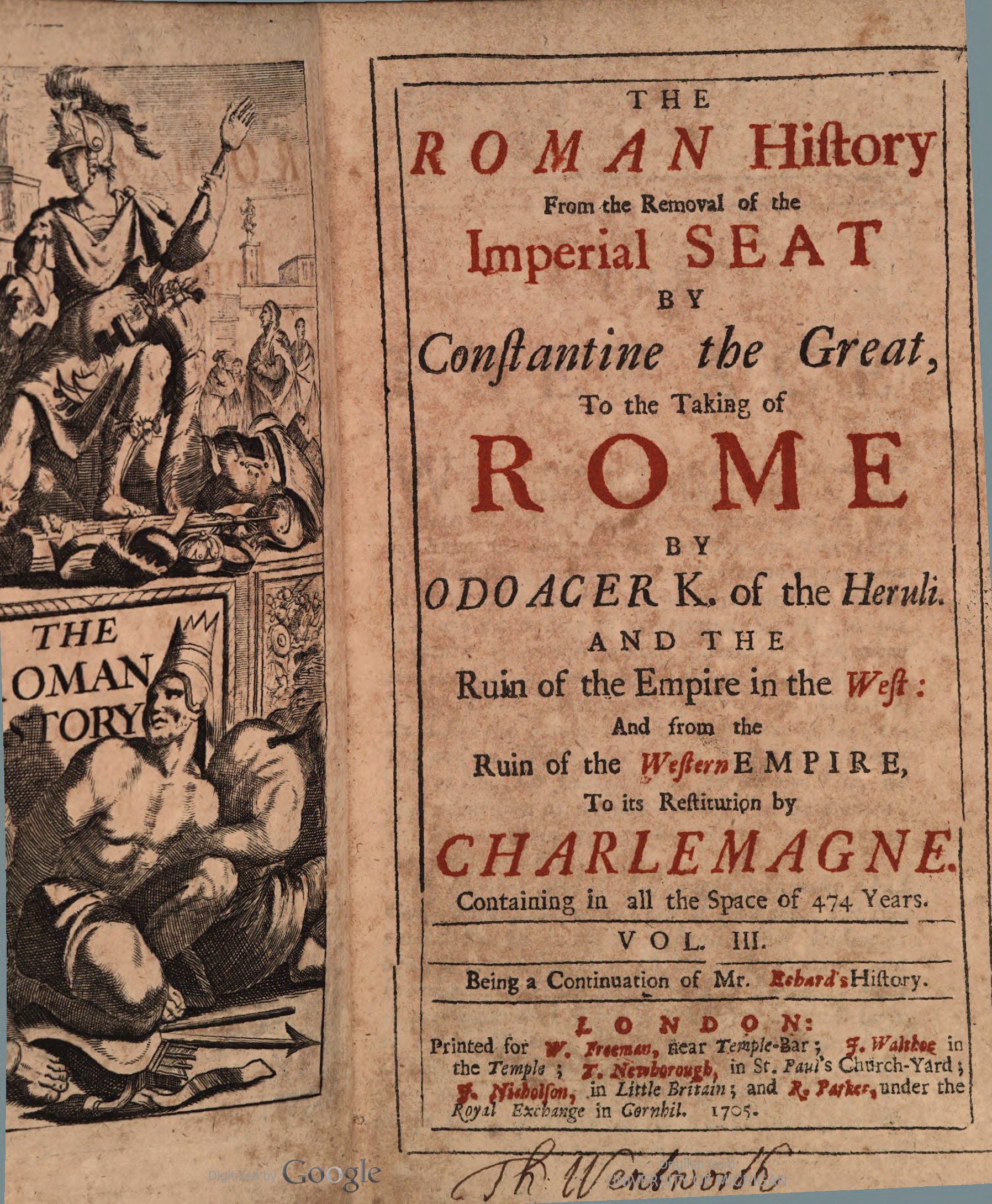

This general sort of title was normal for its time. Here are three other random 18th-century examples:

THE English Theophrastus : OR, THE Manners of the Age. Being the Modern Characters OF THE COURT, the TOWN, and the CITY. The Second Edition. With the Addition of 37 New Characters.

THE ROMAN History From the Removal of the Imperial SEAT By Constantine the Great, To the Taking of ROME BY ODO ACER K. of the Heruli. AND THE Ruin of the Empire in the West : And from the Ruin of the Western EMPIRE To its Restitution by CHARLEMAGNE. Containing in all the Space of 474 Years. VOL. III. Being a Continuation of Mr. Rebard's History.

A DICTIONARY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE : IN WHICH The WORDS are deduced from their ORIGINALS, AND ILLUSTRATED in their DIFFERENT SIGNIFICATIONS BY EXAMPLES from the best WRITERS. TO WHICH ARE PREFIXED, A HISTORY of the LANGUAGE, AND An ENGLISH GRAMMAR. By SAMUEL JOHNSON, A.M. In TWO VOLUMES. VOL. I.

So this leads me to wonder about the longer-term historical trajectory of book titles, in English and in other languages: Overall length, structure, punctuation, font types/sizes/colors, capitalization, line divisions, etc.

There's also more to say about Mr. Sproson's reader — but that's all I have time for this morning.

Gregory Kusnick said,

August 5, 2022 @ 9:32 am

Sproson's title reads more like what today we would call an abstract. So maybe the trend is not that titles got shorter, but that this sort of prefatory material got longer and moved to a separate section in the book.

Gregory Kusnick said,

August 5, 2022 @ 10:21 am

Further thought: your examples predate the 19th-century invention of library card catalogs. So perhaps the space constraints of such catalogs played a role in formalizing the notion of book titles as succinct identifiers rather than rambling descriptions of the contents.

J.W. Brewer said,

August 5, 2022 @ 11:19 am

For reasons that I think are not inconsistent with Gregory Kusnick's, I'm not sure that anything in the Sproson after "meanest Capacity" is usefully thought of as part of the "title.' That said, I think even on a tighter definition of "title" (including a subtitle, whether or not introduced by "or"), there has been a decided move toward comparative brevity in more recent centuries.

Perhaps the analogy is not so much Gregory Kusnick's "abstract" as something less academic, i.e. the sort of description of the work for marketing purposes found on the back cover or flap of the dustjacket or even occasionally on the cover itself. Modern example of the latter: I just pulled off my shelves William D. Zabel's 1995 "The Rich Die Richer and You Can Too." Below the title on the front cover it reads "One of the world's leading estate and tax planners shows how everyone can adapt the special strategies of the wealthy to enrich and enlarge an estate." Perhaps two centuries earlier that would have been worked into the "title" with a transitional word like "wherein," but that additional language is clearly not part of Zabel's actual title. It's not on the title page inside, and not on the spine.

Here's how the full title page of one of the more important books in English society over the relevant centuries (I'm not going to reproduce the typographic variation of what is and isn't in ALLCAPS) describes the contents: "The Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments, and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the Church of England: Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, Pointed as they are to be sung or said in Churches." In practice, no one ever refers to this by any form of title longer than the first four words. One might also note that the last 19 words describe what is technically a *different* book, not part of the BCP strictly speaking but traditionally bound with it in a single volume for the convenience of the intended users. Other editions stretch out the title-page text even further by adding "and the Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons," again reflecting a persnickety notion that the Ordinal is not part of the BCP proper but is included in the same volume for reasons of convenience.

Theo said,

August 5, 2022 @ 11:35 am

SEO (search engine optimization) of the 18th century?

Dick Margulis said,

August 5, 2022 @ 12:12 pm

To Theo's point:

The title page, in earlier centuries, had to do the work that is now done by the front cover, spine, and back cover of a modern book. People do just a book by its cover, and when books were sold as gathered and sewn signatures but without a cover (or, later, with a simple cloth or leather cover with no text beyond the main title and author), the title page was the place to market the book. And when the publisher was either the same as the printing house or a retailer who had commissioned the printing, that merchant's reputation for physical book quality was part of the message.

So the shortening and tightening as the centuries progressed was monotonic until the advent of Amazon, when the trend started to reverse, at least insofar as the lengths of main titles and subtitles was concerned, because now the game is to cram as many keywords into the title as feasible.

Dick Margulis said,

August 5, 2022 @ 12:13 pm

. . . do judge a book . . . , not" do just a book"

Karl Weber said,

August 5, 2022 @ 1:45 pm

As others have commented, over the past 250 years, information about the contents and style of the book presented so as to entice potential readers has migrated from the title (or title page) to other parts of the book and its marketing package–the back panel of a paperback, the flaps of a hardcover dust jacket, and the advertising copy that appears on an Amazon product page.

In addition, having worked in publishing for 40 years, I'd venture a guess that the average length of book titles themselves has gradually declined due to several factors, which include:

(1) The perceived increase in competition for readers' "eyeballs" (publishers' staffs are continually reminding one another, "We have to grab their attention fast!").

(2) The greater flexibility and creativity afforded to cover designers when working with a short title (a one- or two-word title, with the author's name, can be incorporated into a dramatic and eye-catching cover design more easily than a five-, eight-, or ten-word title).

(3) The rise in online book marketing, which means that browsers are often introduced to new books via small, thumbnail images (which are much more likely to be legible and attractive when the cover design is simple rather than complex).

Brian Ogilvie said,

August 5, 2022 @ 2:33 pm

As Dick Margulis has already pointed out, books sold unbound would use the title page to attract the interest of potential readers (except for clandestine works, whose false title pages aimed to turn away interest).

As some data in favor of J. W. Brewer's remarks, it's instructive to compare title pages with contemporary catalogue entries. The humanist Johannes Sambucus's library catalogue has an entry (#563 in Pál Gulyás's edition) for "Pirotegnia del S. Vannuccio Biringuccio Senese //. Venetia Hieronym Giglius et Socij. 1559."

The title page of the book proclaims: "PIROTECHNIA del S. Vannuccio Biringuccio Senese; nella quale si tratta non solo della diversità delle minere, ma ancho di quanto si ricerca alla pratica di esse. E di quanto s'appartiene all'arte della fusione, ò getto, dei metalli. Far campane, arteglierie, fuochi artificiati, et altre diverse cose utilissime. Nuovamente corretta, et ristampata. Con la tavola delle cose notabili. In Venetia, Appresso P. Gironimo Giglio, e compagni. M.D.LIX."*

The cataloguer did not consider the lengthy description to be part of the book's title; he settled on the misspelled "Pirotegnia." Other entries are longer, but they still give a relatively brief title without much description of the contents.

*PYROTECHNICS of Mr. Vannuccio Biringuccio of Siena, in which are discussed not only the diversity of mines but also what is involved in their practice. And what belongs to the art of fusion or casting of metal. Making bells, artillery, fireworks, and other useful things. Newly corrected and reprinted. With a table of noteworthy things. In Venice, by Geronimo Giglio and partners. 1559.

CuConnacht said,

August 5, 2022 @ 4:12 pm

What does the "S.M." appended to Mr Sproson's name mean? Was there a Master of Science/Scientiae Magister degree in the eighteenth century?

Brett Altschul said,

August 5, 2022 @ 4:16 pm

The year 2005 saw the publication of An Almanac of Complete World Knowledge Compiled with Instructive Annotation and Arranged in Useful Order by myself, John Hodgman, a Professional Writer, in The Areas of My Expertise, which Include: Matters Historical, Matters Literary, Matters Cryptozoological, Hobo Matters, Food, Drink & Cheese (a Kind of Food), Squirrels & Lobsters & Eels, Haircuts, Utopia, What Will Happen in the Future, and Most Other Subjects.

Mike D said,

August 5, 2022 @ 7:39 pm

I wonder if any of these long titles are long enough to challenge the conventional view that titles cannot be copyright?

They can be trademarked, as Wisden (cricket statistics) and anyone's use of say the Title : Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Latitude 38° 54' N, Longitude 77° 00' 13" W

(Author: Harlan Ellison) might provole a legal action for 'passimg off'

languagehat said,

August 6, 2022 @ 7:42 am

I'm not sure that anything in the Sproson after "meanest Capacity" is usefully thought of as part of the "title.'

I strongly agree.

GH said,

August 7, 2022 @ 4:05 am

I am not convinced that there is, or has been, a general trend for book titles to get shorter over the last 200 years or so. My impression is that different genres of books all have their own various trends and fashions in titles, lasting maybe a decade or two, so that title lengths are constantly going up for some books and down for others, before the tide turns again.

Academic titles, popular history books, travel books, biographies, political books, self-help books, "literary" fiction, science fiction, fantasy, crime fiction, romance, humor, YA, children's lit… they all have their different "templates" for what a title typically looks like, which then lead to different title lengths. And usually, multiple templates are available to choose from for any particular type of book.

So I think the data is so complex and messy that even if you could draw a linear regression or whatever and find some vague tendency, it would miss the interesting story.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

August 7, 2022 @ 5:12 pm

Do title pages with extensive information about the book, such as Sproson has, become less of a combination of synopsis and sales pitch as publishing trends change? For instance, book pages were once printed on large pages that were folded and sold uncut, so the option to page through the book to look at content was restricted. Some books were sold with cardboard or wrappers to protect them, but were not bound by the publisher. The lengthy title page served more than one function.

Colorful binding with print on the spring and covers, and also colorful dust jackets with promotional information such as a synopsis or brief author bio came later. When the cover, spine, or dust jacket could provide marketing space and the pages were cut as part of book manufacturing, did titles shorten?