The Scalia/Garner canons: Departures from established law

« previous post | next post »

Previously:

Robocalls, legal interpretation, and Bryan Garner

The precursors of the Scalia/Garner canons

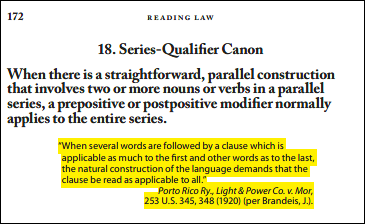

In my last post, I talked about the precursors of the canons from Reading Law that are the primary subject of this series of posts. As I explained there, the Last Antecedent Canon and the Nearest Reasonable Referent Canon are adapted from what is generally known as the Rule of the Last Antecedent (which you should remember not to confuse with the Last Antecedent Canon). And the Series Qualifier Canon was inspired by the pronouncement in a 1920 Supreme Court case that “that “[when] several words are followed by a clause which is applicable as much to the first and other words as to the last, the natural construction of the language demands that the clause be read as applicable to all.”

The purpose of that exercise in intellectual history was to provide the background that’s necessary in order to understand the present post, which will talk about the ways in which the three canons depart from the law as it existed before Bryan Garner and Antonin Scalia wrote Reading Law. Although those departures probably aren’t especially significant in the case of the Last Antecedent and Nearest Reasonable Referent canons (putting aside the confusion and complication they cause), the same isn’t true with respect to the Series Qualifier Canon.

As we’ll see, the default interpretation that is prescribed by the Series Qualifier Canon in a big category of cases is precisely the opposite of what would be prescribed by the Rule of the Last Antecedent. That change is, as far as I’ve been able to determine, unjustified by the caselaw (including the caselaw that was the Series Qualifier Canon’s inspiration). Nor is there any other justification I can think of.

BEFORE DISCUSSING THE WAYS in which the three canons depart from the existing case law, I need to make one thing clear, especially for the benefit of those who aren’t lawyers. Reading Law has no binding legal effect, so nothing that it says has any direct effect on the law of any jurisdiction. However, it has the potential to influence the direction of the law, because judges regard it as a reliable and authoritative statement of what the law is. To the extent that Reading Law is out of step with existing precedent, following its prescriptions can lead to an outcome different from what would be called for under the preexisting law. And even when that doesn’t happen, the book’s deviations from existing law can be a source of needless complexity and confusion, especially when those deviations aren’t recognized for what they are.

With that out of the way, let’s start examining the ways in which the Last Antecedent Canon, the Series Qualifier Canon, and the Nearest Reasonable Referent Canon differ from the existing law.

This examination will start out from the assumption that the Rule of the Last Antecedent represents the existing law. That’s an oversimplification, in that it doesn’t take account of Porto Rico Railway, Light & Power Co. v. Mor, but I’ll bring that into the discussion at the appropriate point. In the meantime, as a reminder of what the Rule of the Last Antecedent says, here are some representative statements of the rule:

“Relative and qualifying words and phrases, grammatically and legally, where no contrary intention appears, refer solely to the last antecedent.” [Sutherland, Statutes and Statutory Construction (1891)]

“An interpretative principle by which a court determines that qualifying words or phrases modify the words or phrases immediately preceding them and not words or phrases more remote, unless the extension is necessary from the context or the spirit of the entire writing.” [Black’s Law Dictionary (7th ed. 1999, 8th ed. 2004, 9th ed. 2009; Bryan A. Garner, editor in chief)]

“A limiting clause or phrase … should ordinarily be read as modifying only the noun or phrase that it immediately follows[.]” [Barnhart v. Thomas (U.S. Supreme Court 2003) (from the majority opinion by Justice Scalia)]

And as another reminder: Don’t confuse the Rule of the Last Antecedent, which has existed in its present form for more than 100 years, with the Last Antecedent Canon, which first made its appearance in 2012, when it was introduced in the pages of Reading Law.

IN COMPARING the three Scalia/Garner canons against the Rule of the Last Antecedent, I’ll begin with the issue that I’ll refer to as “coverage” or “scope”: the set of issues as to which the Rule of the Last Antecedent and each of the canons prescribes out default interpretation.

What Reading Law did was to divide Rule of the Last Antecedent’s coverage into three parts, each of which was assigned to a different one of the canons we’re looking at. The dividing lines were drawn on the basis of grammatical criteria. Issues relating to identifying the antecedents of “pronoun[s], relative pronoun[s], or demonstrative adjective[s] were assigned to the Last Antecedent Canon. Issues relating to ambiguities in the scope of modifiers were divided between the other two canons, with the Series Qualifier Canon applying “when there is a straightforward, parallel construction that involves all nouns or verbs in a series” and the Nearest Reasonable Referent Canon covering what was left over.

One effect of this allocation of issues is that the Last Antecedent Canon’s coverage is significantly smaller than Rule of the Last Antecedent’s. But if you’re Old School, you can take solace in the fact that the reduction in scope isn’t as large as might appear at first. That’s because, as we’ll see, the coverage of Last Antecedent Canon overlaps to a significant extent with that of the Series Qualifier Canon.

The second departure from preexisting law relates only to the Series Qualifier and Nearest Reasonable Referent Canons. Whereas issues involving modifiers under the Rule of the Last Antecedent were limited to backward-looking modifiers—words or phrases that come after the chunks of text they modify, as in lawyers and doctors from Texas (“postpositive” modifiers, to use Reading Law’s terminology)—the Series Qualifier and Nearest Reasonable Referent canons cover not only those, but also forward-looking modifiers such as highly educated lawyers and doctors (“prepositive” modifiers).

Until Reading Law came out, there was, as far as I’ve been able to tell, no recognized canon dealing with such modifiers. There were, to be sure, individual cases in which courts said that prepositive modifiers apply to each item that follows them. But I’m aware of nothing to suggest that those statements had attained canonical status.

That said, I’m not particularly worked up about this difference between Reading Law and the prior caselaw. What Garner and Scalia say about prepositive modifiers is generally consistent with the cases I’ve read. So if that were the only way in which Reading Law departs from the existing law, I probably wouldn’t have been motivated to write this series of posts. I’ll therefore have nothing more to say about issues involving prepositive modification.

This brings us, finally to the Series Qualifier Canon as it applies to postpositive modifiers. And unlike the innovations that I’ve discussed so far, the default rule prescribed by the SQC as to such modifiers is diametrically opposed to the one prescribed by the Rule of the Last Antecedent.

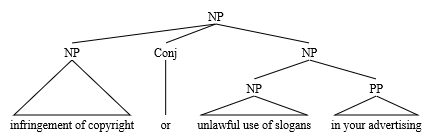

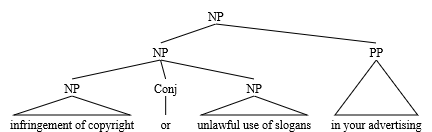

The Rule of the Last Antecedent establishes a preference for low-attachment interpretations, in which the modifier is understood to apply only to the word or phrase that immediately precedes the modifier:

But the Series Qualifier Canon in effect states a preference for high-attachment interpretations, with the modifier being understood to apply to the larger phrase of which the closest “antecedent” is a part:

Thus, for issues within the scope of the Series Qualifier Canon, the result of following Reading Law rather than the preexisting Rule of the Last Antecedent would be to change from a default rule of X to a default rule of not-X. That’s a rather significant change, yet Garner and Scalia didn’t point out that any change had been made. Nor, obviously, did they provide any explanation for the change that they didn’t disclose.

Be that as it may, some uncertainty exists as to the extent to which the Series Qualifier Canon displaces the Rule of the Last Antecedent. But there’s a twist, which can be seen either as lessening the effects of that change or as increasing the disruption, depending on how you want to look at it: the Series Qualifier Canon’s coverage overlaps with that of the Last Antecedent Canon.

Recall that the Last Antecedent Canon covers issues in which there is ambiguity as to what word or phrase is the antecedent of “a pronoun, relative pronoun, or demonstrative adjective.” (Garner uses demonstrative adjective to refer to words such as this and that, which are referred to in the Cambridge Grammar of the English Language as “demonstrative determinatives.”)

Putting aside issues involving relative pronouns, the coverage of the Last Antecedent Canon won’t ordinarily (if ever) overlap with that of the Series Qualifier Canon. That covers issues involving modifiers, and it seems unlikely to me that nonrelative pronouns or demonstrative adjectives could act as modifiers. (And in any event my impression is that ambiguities involving nonrelative pronouns or demonstrative adjectives aren’t a frequent problem in statutory interpretation.)

But the situation is different as to relative pronouns. Relative pronouns introduce relative clauses, and restrictive relative clauses (integrated relative clauses, in CGEL’s terminology) function as modifiers. For example:

institutions and societies that are charitable in nature

a wall or fence that is solid

Because the relative clause in each of these phrases begins with that (which Reading Law classifies as a relative pronoun), each phrase is covered by the Last Antecedent Canon. But at the same time, the relative clause in each phrase immediately follows a series of nouns, so that the phrase is also covered by the Series Qualifier Canon. So in an interpretive dispute involving one of these phrases, Reading Law would provide two mutually inconsistent default rules.

This overlap in the coverage of Last Antecedent and Series Qualifier Canons goes unnoticed in Reading Law, despite being on display in plain view. The two phrases above (institutions and societies that are charitable in nature and a wall or fence that is solid) are taken from Reading Law (page 148), which offers them as examples of the Series Qualifier Canon in action. In both cases, the book says that the relative clause modifies both nouns. Yet three pages earlier, in the chapter on the Last Antecedent Canon, a series of verb phrases is offered as an illustration of that canon in action (boldfacing added, footnotes omitted):

In what has been called the “seminal authority” on the last-antecedent canon, Barnhart v. Thomas, the Supreme Court of the United States illustrated how the rule works. Let us say that parents warn a teenage son: “You will be punished if you throw a party or engage in any other activity that damages the house.” With this homey example, the Court said in a unanimous opinion: “If the son nevertheless throws a party and is caught, he should hardly be able to avoid punishment by arguing that the house was not damaged.” The relative pronoun that attaches only to other activity, not to party as well.

The relevant phrase in the parents’ instruction (throw a party or engage in any other activity) is probably within the Series Qualifier Canon’s scope. Although the phrase contains both nouns and verbs as well as words belonging to other parts of speech, and therefore arguably doesn’t satisfy a strictly literal reading of the canon’s scope (“a straightforward, parallel construction that involves all nouns or verbs in a series”), the fact is that Reading Law itself doesn’t take that description literally. That is clear from the book’s use of the following chunks of text as examples illustrating the application of the Series Qualifier Canon (pp. 149–151):

"infringement of copyright or improper or unlawful use of slogans in your advertising" [from Phoenix Control Systems v. Ins. Co. of America (Ariz. 1990)]

"marshals, sheriffs, prison or jail wardens, or their deputies, policemen or other duly appointed law-enforcement officers, or to members of the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps of the United States or of the National Guard when on duty" [from Pritchett v. United States (D.C. Cir. 1972)]

And in any event, Reading Law’s discussion of the parents’ instruction removes any possible doubt that the Last Antecedent Canon extends to relative clauses that serve as postpositive modifiers.

I WANT TO RETURN NOW to my statement that the Series Qualifier Canon represents a departure from established law. Although the canon is obviously inconsistent with the Rule of the Last Antecedent, that doesn’t rule out the possibility that there is some other basis in the caselaw on which it can be justified. So I’ll try to explain why I think that no such basis exists.

The obvious place to start is with the statement that I described as the canon’s precursor, from the 1920 Supreme Court decision Porto Rico Railway, Light & Power Co. v. Mor: “When several words are followed by a clause which is applicable as much to the first and other words as to the last, the natural construction of the language demands that the clause be read as applicable to all.”

But that doesn’t provide a justification for the Series Qualifier Canon. Although the statement calls for the interpretive result as is called for by the canon’s default rule, its coverage—the set of issues for which it provides the relevant rule—is entirely different. Whereas the Series Qualifier Canon’s coverage is defined in syntactic terms, by specifying the relevant lexical categories, the statement from Porto Rico Railway is framed in terms of semantics (albeit utterly vacuous semantics).

According to the statement in Porto Rico Railway, the interpretive outcome it specifies is required “[w]hen several words are followed by a clause which is applicable as much to the first and other words as to the last.” But that statement is circular, giving no guidance at all. The question whether the clause is “equally applicable” to all the words is precisely the interpretive question that needs to be answered.

That is why I said that the statement from Porto Rico Railway was the inspiration for the Series Qualifier Canon, not the source from which it was derived. My assumption has been that Garner wanted Reading Law to include a canon based on Porto Rico Railway, but recognized that if he did so, the canon would have to specify some basis on which to know when to apply it and when not to.

While the second half of the last sentence represents speculation, my surmise that the canon is somehow connected with Porto Rico Railway has been confirmed by Garner himself. In my last post I pointed to a statement in Noah Duguid’s brief in the Facebook case, and the other day I updated that post to note something that had slipped my mind. Several years ago Garner sent me a draft revision of several chapters of Reading Law, asking for my comments. The chapters were intended for a planned second edition of the book (which never came to fruition), and one of them was on the Series Qualifier Canon. The first change to that chapter was the addition of this epigraph, just below the chapter title:

(For background, see the update at the end of this post.)

Given all of this, Porto Rico Railway’s status as the precursor of the Series Qualifier Canon seems to me to be pretty clear.

BUT THAT RAISES another question: Why?

What made Garner want to take what was essentially a tautology and convert it into a rule that actually had some determinate content? And why, having decided to do so, did he decide that the new canon should apply to issues involving “a straightforward, parallel construction that involves all nouns or verbs in a series”?

Unfortunately, I don’t have an answer to those questions. But there is one thing that I’m pretty sure of, and it’s that with respect to postpositive modifiers, the Series Qualifier Canon can’t be justified as accurately reflecting the state of the law as it existed when Reading Law was published.

We’ll start with what Reading Law says in its chapter on the Series Qualifier Canon. With regard to prepositive modifiers, six cases were cited in support of the canon; all of them adopted interpretations consistent with what the canon would require, and four of them justified their interpretations by invoking considerations of grammar. In contrast, only three cases were cited as to postpositive modification, two of which (United States v. Pritchett and Phoenix Control Systems v. Insurance Co. of North America) count as precedent against the Series Qualifier Canon, in that both cases applied the Rule of the Last Antecedent and followed its default interpretation. While the third case doesn’t present a similar conflict with the canon, and interpreted the statute consistently with what the SQC would require, the opinion gives no reason to think that that interpretation can be attributed to the grammatical factors specified by the Series Qualifier Canon.

Reading Law therefore provides readers with nothing (beyond the authors’ reputations) that would justify a belief that the substance of the Series Qualifier Canon (as it relates to postpositive modification) was then a part of U.S. law, or ever had been.

But rather than leave things at that, let’s look at whether there’s anything else in the case law that could give the Series Qualifier Canon (as applied to postpositive modification) a grounding in precedent.

There’s one data point that seems at first like it might offer some promise. Based on my review of maybe a third to a half of the cases that recited the statement from Porto Rico Railway, it looks like the text at issue would in most cases be within the scope of the Series Qualifier Canon. But for several reasons, I don’t think that can justify a conclusion that the canon reflects the preexisting caselaw.

First of all, there’s nothing I’ve seen in any case to suggest that the court’s reason for invoking Porto Rico Railway was that the text displayed the grammatical characteristics that were ultimately enshrined in the Series Qualifier Canon.

To begin with, many of the cases citing Porto Rico Railway are inconsistent with Reading Law’s formulation of the Series Qualifier, Last Antecedent, and Nearest Reasonable Referent Canons as each covering a distinct set of issues, with no overlap (or at least none the authors were aware of). Many of the cases that cite Porto Rico Railway also cite and discuss the Rule of the Last Antecedent, and in all such cases I’m aware of, the focus wasn’t on coverage—i.e., on whether the case presented a linguistic issue of the kind that the Rule of the Last Antecedent could deal with. Rather, the focus was on whether to adopt the Rule’s default interpretation, or instead to override that interpretation based on factors specific to the case. In fact, some cases described Porto Rico Railway as an exception to the Rule of the Last Antecedent, which seems to me to be at odds with the Series Qualifier Canon’s narrow focus on grammar.

Now let’s expand our focus beyond the cases that cited Porto Rico Railway. As we’ll see, doing so presents further problems for any attempt to trace the Series Qualifier Canon back to existing caselaw. Although cases covered by the Series Qualifier Canon predominate among the cases citing Porto Rico Railway, those aren’t the only cases that were within the canon’s scope. In fact, I think it’s likely that they didn’t even account for the majority of cases to which the canon would have applied, had it existed.

I estimate (based on extrapolation from a sample of 86 cases, representing roughly 10% of the cases citing the Rule of the Last Antecedent) that cases invoking Porto Rico Railway were substantially outnumbered by those in which the Series Qualifier Canon would have applied but the court nevertheless cited the Rule of the Last Antecedent.

In some of those cases, the court adopted the interpretation prescribed by the Rule—a result inconsistent with the Series Qualifier Canon. But the other cases were also inconsistent with the canon even though they adopted the interpretation that the canon favors.

That’s because the court’s reasoning was inconsistent with the Series Qualifier Canon. Under the canon, it’s the grammatical characteristics of the text that determines the default interpretation. When those characteristics are present, therefore, consideration of a different default interpretation would, under Reading Law’s framework, be precluded. But in none of the cases I’m discussing did the court suggest that the grammatical characteristics of the relevant text render the Rule of the Last Antecedent irrelevant.

Given what I’ve laid out here, I see no reason to think that the Series Qualifier Canon (as it relates to postpositive modification) has any pedigree that goes back any further than the publication of Reading Law.

And consider this: Bryan Garner is aware of my argument about the Series Qualifier Canon (though not necessarily in all the detail I’ve provided here), and I’ve invited him more than once to respond if he thinks I’m mistaken. It’s reasonable to think that if Garner had any evidence supporting the canon’s validity, he would let me know about it. But except as to one point relating to prepositive modification (which led me to issue a correction), he’s had nothing to say.

That silence speaks volumes.

Under these circumstances, I don’t know how one can avoid the conclusion that the canon is to a large extent an exercise in creative writing.

Coming next: Facebook v. Duguid: The briefs, the oral argument, and my take.

Cross-posted on LAWnLinguistics.

Philip Taylor said,

December 20, 2020 @ 3:26 pm

In the example :

does the presence of "other" not significantly affect the interpretation ? Had the parents said “You will be punished if you throw a party or engage in any activity that damages the house", then the "that damages the house" would clearly apply only to "any activity". But the use of "other" means, to this reader at least, that "throw[ing] a party" is, in the eyes of the parents, "[an] activity that damages the house". I am surprised that the Supreme Court did not reach the same conclusion.

D.O. said,

December 20, 2020 @ 3:47 pm

IANAL, but I feel the quote from Porto Rico Railway [“when several words are followed by a clause which is applicable as much to the first and other words as to the last.”] is not a tautology. It says that when a qualifying phrase can be reasonably read as applying to all parallel terms, it should be read as indeed applying to all of them. This is a huge hole in the "last antecedent" rule, but that is what it says. If you look at the exact phrase in question in Porto Rico Railway

Said district court shall have jurisdiction of all controversies where all of the parties on either side of the controversy are citizens or subjects of a foreign State or States, or citizens of a State, Territory, or District of the United States not domiciled in Porto Rico, …

it is obvious that both parts of the condition ("citizens or subjects of a foreign State or States" and "citizens of a State, Territory, or District of the United States") are heavy, which usually, in ordinary language, would make high attachment of the qualifier less probable. If J. Brandeis felt that even this situation requires high attachment, there is really no place for the "last antecedent" rule.

In reality IMHO there is no way to disambiguate between high and low attachment and follow the plain language practice because plain language practice is inconsistent. Courts have to either a) adopt hard and fast rule, which in some cases would lead to strange results or b) acknowledge the ambiguity and decide on a case by case basis on primarily non-linguistic grounds. Or they can engage in what seems to be a normal practice of doing (b) while pretending that they are doing (a), but changing the rule every time.

Gregory Kusnick said,

December 20, 2020 @ 9:03 pm

I agree with D.O. that the statement in question is not tautological.

I can't resist adding that Porto Rico Railway, Light & Power calls to mind the former name of the Western Washington electric utility, Puget Sound Power & Light. I was always tempted to insert a comma after "Sound".

Neal Goldfarb said,

December 20, 2020 @ 9:19 pm

In response to Phillip Taylor:

Phrases such as "other activity that damages the house" are ambiguous as to the scope of "other":

(1) [other activity] [that damages the house]

(2) [other] [activity that damages the house]

Reading (1) corresponds to the interpretation that is assumed in Scalia's hypothetical example: activity other than a party is prohibited only if it damage the house.

Reading (2) corresponds to something like "other house-damaging activity," and it generates a presupposition that a party would damage the house. That reading would ordinarily be dispreferred, but it can be forced by pronouncing the phrase (or hearing it inside your head, if you're reading it) with stress on "other."

On reading (2), the question arises as to whether the presupposition should be given legal effect by treating "that damages the house" as modifying not only "activity" but also "party."

Philip Taylor said,

December 21, 2020 @ 3:51 am

I agree that there are two possible interpretations ('bindings') of "other", but if the intended binding was '(1) [other activity] [that damages the house]' then "other" was redundant and should have been omitted. All that needed have been said was “You will be punished if you throw a party or engage in any activity that damages the house”. Since the "other" was not omitted, it must have been inserted for a reason, and I would argue that that reason was that '(2) [other] [activity that damages the house]' was the intended meaning.

Julian said,

December 21, 2020 @ 10:04 pm

Surely the procedure for parsing these attachment ambiguities is:

1. use common sense considering the meaning and context and legislative intent. Thus, ‘[men or women] [who are over 65] may apply for a senior’s card’ has high attachment. ‘[Men] or [women who are pregnant] may participate in the clinical trial’ has low attachment (contrary to the Series Qualifier Canon).

2. If 1. is not conclusive, apply some logical reasoning if available, such as the discussion in this thread of the party example The presence of ‘other’ implies high attachment (‘You will be punished if you [throw a party or engage in any other activity] [that damages the house’), because low attachment (… [throw a party] or [engage in any other activity that damages the house]) implies that a party will unavoidably damage the house, which is unwarranted. In general, ‘the legislators probably meant A, because if they meant B that would imply that they thought X, which is unlikely.’

3. If 1. and 2. are not conclusive, apply a grammatical rule such as the Garner/Scalia canons, as a last resort.

But if the only rule that you can frame with enough generality to be useful gives absurd results when you apply it to the examples that you’ve decided at 1. and 2, that’s not much use, is it?

To put it anouther way, if your rule at 3 has to be caveated with ‘where no contrary intention appears’ or ‘subject to the spirit of the entire writing’, you’re back where you started: using the meaning and context to try to decide whether a contrary intention appears. So why bother with the rule?

To put it a third way, if meaning, context and logic can’t decide the issue, then surely the grammatical rule is just a face-saving way of avoiding a coin toss. Unless there was some evidence that in general the rule corresponds to actual legislative intent (which would have to be discovered in some other way) to an extent usefully more than a coin toss.