Lawyers as linguists

« previous post | next post »

Alison Frankel, "Lexicographer (and Scalia co-author) joins plaintiffs’ team in Facebook TCPA case at SCOTUS", Reuters 10/20/2020:

Can a lexicographer fend off the combined forces of Facebook, the Justice Department and the entire U.S. business lobby at the U.S. Supreme Court?

What if said lexicographer is also the co-author, with Justice Antonin Scalia, of a landmark book about textualism that is cited multiple times in the other side’s briefs?

Bryan Garner – the Black’s Law Dictionary editor, legal writing consultant and, with Justice Scalia, author of Reading Law – has joined the Supreme Court team of Noah Duguid, a Montana man who sued Facebook in 2015 for violating the Telephone Consumer Protection Act. And though he’s only been working with Duguid’s other lawyers for a matter of weeks, Garner’s influence on Duguid’s just-filed merits brief is unmistakable. Who else could so boldly assert that the TCPA’s meaning depends on whether the statute’s “adverbial modifier” applies to just one or both “disjunctive verbs” with a “common object”?

Without taking anything away from the well-deserved kudos for Bryan Garner, I want to underline how odd it is to suggest that without his help, lawyers couldn't be expected to understand simple grammatical concepts like "adverbial modifier", "disjunctive verb", and "common object".

The summary of Facebook, Inc. v. Duguid at oyez.org:

Noah Duguid brought this lawsuit because Facebook sent him numerous automatic text messages without his consent. Duguid did not use Facebook, yet for approximately ten months, the social media company repeatedly alerted him by text message that someone was attempting to access his (nonexistent) Facebook account.

Duguid sued Facebook for violating a provision of the Telephone and Consumer Protection Act of 1991 that forbids calls placed using an automated telephone dialing system (“ATDS”), or autodialer. Facebook moved to dismiss Duguid’s claims for two alternate reasons. Of relevance here, Facebook argued that the equipment it used to send text messages to Duguid is not an ATDS within the meaning of the statute. The district court dismissed the claim, and a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed, finding Facebook’s equipment plausibly falls within the definition of an ATDS. TCPA defines an ATDS as a device with the capacity “to store or produce telephone numbers to be called, using a random or sequential number generator.” Ninth Circuit precedent further clarifies that an ATDS “need not be able to use a random or sequential generator to store numbers,” only that it “have the capacity to store numbers to be called and to dial such numbers automatically.”

The relevant section of Telephone Consumer Protection Act 47 U.S.C. § 227:

SEC. 227. [47 U.S.C. 227] RESTRICTIONS ON THE USE OF TELEPHONE EQUIPMENT

(a) DEFINITIONS.— As used in this section—

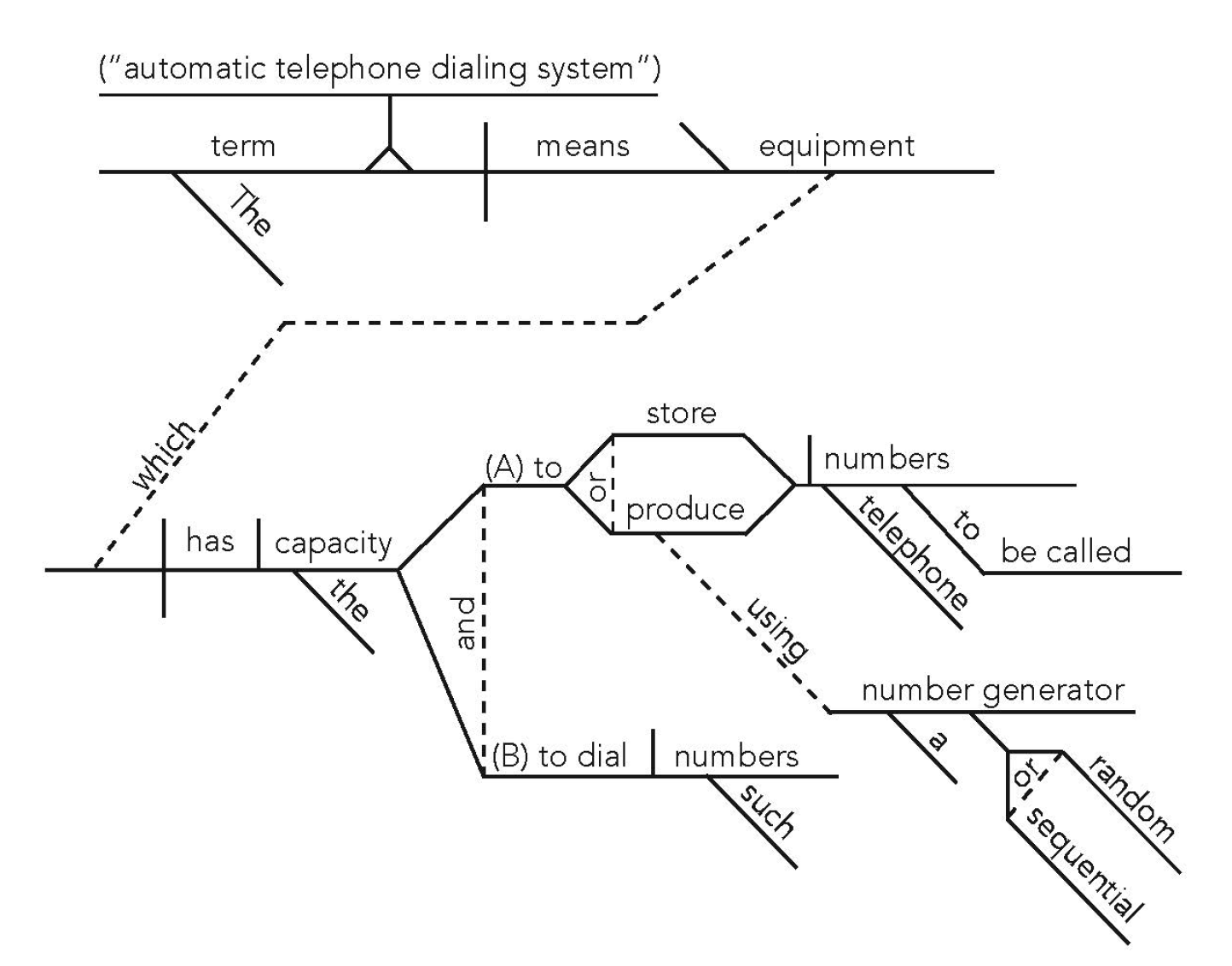

(1) The term “automatic telephone dialing system” means equipment which has the

capacity—

(A) to store or produce telephone numbers to be called, using a random or

sequential number generator; and

(B) to dial such numbers.

Noah Duguid's brief starts like this:

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the Telephone Consumer Protection Act’s definition of “automatic telephone dialing system,” 47 U.S.C. § 227(a)(1), encompasses a device that can store and automatically dial telephone numbers without using a random or sequential number generator.

Pages 16-22 of the brief deal argue that "The correct grammatical reading of the definition aligns with the semantic content of the words" — I invite you to read through the argument yourself. Here I'll just note that the brief presents this charmingly antique figure to express the structure of the sentence:

Diagrams of this particular kind were introduced in Alonzo Reed and Brainard Kellogg's 1878 work Higher Lessons in English ("A Work on English Grammar and Composition : in which the Science of the Language is Made Tributary to the Art of Expression : a Course of Practical Lessons Carefully Graded, and Adapted to Every Day Use in the School-room"), and were taught in American primary schools at least through the 1950s — although when I encountered them in (what was then still called) "Grammar School", my teachers made it clear that they didn't really understand the system at all, and I would be surprised to learn that many lawyers or judges today are in a much better position. These days, few American students are taught anything at all about grammatical analysis — but a Reed-Kellogg diagram strikes me as an odd way to bring grammatical analysis to bear on statutory interpretation in 2020, instead of a modern constituent structure or dependency structure diagram. (Though lawyers and judges are not any more likely to understand those, alas…)

(See "Diagrammatic Excitement" 3/27/2012 and "Sentence Diagramming" 1/1/2014 for some additional history.)

The full SCOTUS docket for this case is available from scotusblog.

And the lower court opinion is here.

Gregory Kusnick said,

October 21, 2020 @ 10:24 am

I gather that Facebook argues that their system does not meet the definition of an ATDS because it does not "store

[…] telephone numbers […] using a random or sequential number generator".

But this claim is almost certainly false. If the telephone numbers are stored in a database table with a primary key, that key is almost certainly a unique number generated either randomly or sequentially.

[(myl) Excellent point, which hinges on the meaning of using rather than the relative scope of modifiers and disjunctions. Have you looked to see whether this point has come up in any of the arguments so far?]

chris said,

October 21, 2020 @ 11:12 am

Initially I thought that as the diagram shows, "using a random or sequential number generator" can only sensibly be applied to "generate" and not "store", but Gregory Kusnick's point that storage in fact *can* also use a random or sequential number generator is well taken.

It seems odd to me that the outcome of the case might hinge on the technical details of how Facebook's system stores phone numbers, but if the definition hasn't been updated in 29 years, I suppose that sort of thing might be expected.

However, the last sentence of the Oyez summary might make this issue irrelevant — I assume that it's not disputed that the equipment both stored and dialed Duguid's number, in the process proving that it was capable of doing so — unless of course Facebook is asking the SC to overturn the 9C precedent Oyez refers to.

Richard Hershberger said,

October 21, 2020 @ 11:13 am

My question is what does being a lexicographer, especially of a specialist dictionary, have to do with syntactic analysis? Sure, a lexicographer has to know a noun from a verb, but analyzing complex sentences isn't part of the job. Frankly, I wonder what Garner brings to this apart from his name, for which I assume he is being paid handsomely. Also, his using a comically outdated analytical scheme feels just so expected.

Jake Wildstrom said,

October 21, 2020 @ 12:08 pm

Surely just as Facebook's proposed definition of an ATDS is too narrow, Duguid's is too broad? Because every single telephone produced in the last 30 years or so "has the capacity to store numbers to be called and to dial such numbers".

It seems that what the authors of that passage wanted to restrict was systems which made calls without active human instruction to do so (and when the TCPS was passed, that activity aligned exactly with the use of a sequential or random telephone number generator), but "here's what they obviously meant to say" is not really a winning legal argument, I guess.

Gregory Kusnick said,

October 21, 2020 @ 12:19 pm

I don't see any reference to how numbers are stored in Duguid's brief, Facebook's brief, or the Ninth Circuit opinion. Facebook's somewhat convoluted explanation of what it means to "store numbers using a random or sequential number generator" seems to be to generate them (randomly or sequentially) and then store them for later use.

I agree with the Ninth Circuit's analysis that this would make the use of "store or produce" in the statute redundant, and therefore can't be what the legislators intended. Any sensible talk of storage ought to mean the collection and storage of numbers as distinct from their automatic generation.

D.O. said,

October 21, 2020 @ 12:57 pm

I disagree with Gregory Kusnick. First, it seems that legislators are in general inclined to use nearly synonymous terms just to be sure that they covered all relevant cases and high degree of overlap between "store" and "produce" is not the reason to think that the "store" part should be wholly distinct. Second, in my entirely non-telemarketing practice, I both stored random or sequentially generated numbers for future use and also produced them on the spot without storing as part of a larger calculation. They were not the telephone numbers though.

Jon W said,

October 21, 2020 @ 1:28 pm

Mrs. Silverstein (the assistant principal, who stepped in when our regular teacher left mid-year) taught my fifth-grade class how to diagram sentences this way in 1968-69. It seemed plain that we were learning arcane knowledge that had otherwise long passed off this earth.

Gregory Kusnick said,

October 21, 2020 @ 2:21 pm

I grant that legislation may often be unclear in intent and redundant in language. But the court's point is that it's not their job to copy-edit the statute to omit needless words. If it says "store or produce" rather than just "produce", the court has to assume that the legislature meant to draw some salient distinction.

Facebook's argument that the "plain meaning" of "store or produce" can only be "produce and then (optionally) store" strikes me as tendentious and disingenuous. I guess we'll see if SCOTUS agrees.

Julian said,

October 21, 2020 @ 4:38 pm

Your linked post of 10 October on dependency grammar v. constituency grammar ends: 'But the various versions of the two formalisms lend themselves variously to various applications — more on this later.'

Looking forward to the next post on this, if I haven't missed it already. Thanks

Julian said,

October 21, 2020 @ 5:09 pm

Never learnt any sort of diagramming at school. But surfing the linked posts, I've now suddenly realised why I deeply, deeply don't get Reed Kellog.

It's because the order that words present to you eye in the diagram does not cue the constituent structure.

For example,at https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=9431 we have

'Our national resources are developed by an earnest culture of the arts of peace.'

I read the RK diagram from left to right as: resources our national are by developed culture earnest an of arts the of peace

In a tree diagram at least you can read the sentence at the bottom.

Haamu said,

October 21, 2020 @ 7:37 pm

After reading both briefs, I find that Facebook has the better of a purely syntactic argument, while Duguid wins if semantics, technical accuracy, and legislative purpose/intent are considered (which are somewhat dubious advantages before a Supreme Court that's becoming ever more textualist/originalist).

For me, on syntax alone, "using a random or sequential number generator" applies to both "store" and "produce" because their common direct object ("telephone numbers to be called") intervenes. But the crux of Garner's argument for Duguid is not purely syntactic: You only apply "using…" (or any adverbial) to the first verb if the result makes sense. The semantic component of this approach just highlights the fact that the diagram doesn't add a scintilla of clarity.

A few supporting examples are provided in Duguid's brief, the clearest being

Bad drafting aside, I buy this. Semantically, "using a random or sequential number generator" just doesn't apply sensibly to "to store." (I'm discounting Gregory Kusnick's observation about primary keys: I can't imagine a legislature that would understand, let alone intend, such a reading, and there are various plausible storage schemes that don't require such keys, which would invite literalist nitpicking.)

The problem with Garner/Duguid prevailing over Facebook's purely syntactic argument is that they have to depend on judges to get a mildly technical point about "to store," and many just won't.

It's too bad the drafters of the TCPA didn't choose "to retrieve" instead of "to store." That's the more salient idea, anyway. It's not necessary for an automated dialing system to generate or store its own numbers if it can just consult a list compiled by somebody else, which is probably the far more common scenario nowadays. Even if Facebook compiled the list itself, it could easily contend (and I'm surprised it didn't) that the number-storage capability was housed in a different system. The retrieval capability, however, could not be.

The biggest flaw in Duguid's case may be that he had to base it on the TCPA, when the central issues in his complaint have to do with data privacy and consent. Presumably, if he lived in California or the EU, he'd be in much better shape.

Orin K Hargraves said,

October 21, 2020 @ 8:30 pm

As a lexicographer I find this post particularly heartwarming. We find so little meaningful and engaging work these days.

I disagree with Mr. Hershberger's assertion in "what does being a lexicographer, especially of a specialist dictionary, have to do with syntactic analysis? Sure, a lexicographer has to know a noun from a verb, but analyzing complex sentences isn't part of the job."

In fact it is our job regularly parse and tag boatloads of complex sentences ably and quickly; otherwise we would not be able to arrive at workable sense divisions for polysemous words in the amount of time we have to do it.

Orbeiter said,

October 22, 2020 @ 2:17 am

Someone probably put in this man's number, at random, when signing up for an account and Facebook has no way of knowing that that happened–unless he were to tell them.

Now if Facebook continued to send messages after he told them to desist, he would have a case that they were being a nuisance. On the other hand, I find the naked allegation of "automatic dialling"–as a sheer accusation–absurd. Of course modern internet services have to automatically message their patrons, supposed or otherwise, from a list using computer automation. The thing that the Telephone Act is supposed to target is *deliberate* automated dialling of people who aren't already customers.

WA said,

October 22, 2020 @ 1:55 pm

Gregory Kusnick is correct.

As an attorney, I have been following this debate for over a year. I will note that many lawyers and judges in district and circuit courts around the country have analyzed the question of what constitutes an autodialer under the TCPA. This question has been analyzed dozens if not hundreds of times. Often those analyzing the question will comment in passing that they don't quite understand how a number could be "stored" using a random or sequential number generator, or what that would even mean, but they just proceed on.

However, I know some attorneys who have argued in their filings recently, in anticipation for how the Supreme Court might rule, that a common database will store records using a sequential number generator.

J.W. Brewer said,

October 22, 2020 @ 2:22 pm

The "antique" style of diagram is most likely to strike the reader as weird if the reader is already familiar with what "a modern constituent structure or dependency structure diagram" looks like. Since we are assuming the target audience here probably lacks that familiarity (and since there's still a Justice or two older than myl who might have had grammar-school exposure to the antique style), the diagram used seems fine in that sense. Of course what you might really want is two diagrams in the same style, each for one of the rival parsings of the same text, but maybe the side Garner is working with didn't think laying out the "wrong" interpretation in the same fashion would help them?

Garrett Wollman said,

October 22, 2020 @ 2:42 pm

I believe I'm at least 15 years younger than Mark and I definitely learned Reed-Kellogg diagramming in 5th or 6th grade. Of course it was a parochial school so one wouldn't necessarily assume the curriculum to be exactly /au courant/ but it's unquestionably the case that at least in Vermont in the early 1980s it was still being taught, so even younger lawyers, if they went to a particularly conservative or religious school would likely have learned this style. Even if they have since forgotten it, R-K will surely look familiar in a way that modern tree diagrams don't.

J.W. Brewer said,

October 22, 2020 @ 2:50 pm

I am intrigued by the footnote "See George O. Curme, A Grammar of the English Language:

Syntax 279 (1931) (explaining that with adverbials of manner, “the present participle is exceedingly frequent” as the lead-in word—here using)." I can't recall ever hearing of Curme or this work and even assuming it might have been a well-known reference in its day I'd be interested to learn if anyone here who is Justice Breyer's age or younger has ever read it.

This is particularly interesting because if true the point that seems to be being made, i.e. that the use of present participle is on a frequency-based analysis fully consistent with the parse that Garner's client is arguing for, seems exactly like the sort of thing more recent sources who have been able to do "big data" work in corpora would have something to say about. Unless perhaps the problem is that the Curme cite is being used to back up a claim phrased using Garner's own preferred analysis and/or terminology which is out of step with that used by the folks who've been doing recent corpus linguistics?

Richard Hershberger said,

October 22, 2020 @ 3:29 pm

@J.W. Brewer: I not only have read it (not, I admit, straight through), I own a copy of the two-volume 1978 edition. Why? Obsolete grammars is one of my more eccentric hobbies. Curme is interesting. He isn't a crank or an idiot by any means, but this was a transitional period. 19th century schoolbook grammar was showing cracks. 20th century analysis was making its appearance, but was at an early stage. The result is a 19th century foundation with the beginnings of 20th century analysis built on top. Going from memory, he talks about determiners pretty much like a modern linguist would, and has a sense that phrasal verbs exist but what exactly they are was not yet worked out. Then he sticks this onto 19th century analysis.

Michael Watts said,

October 22, 2020 @ 6:08 pm

I see it as turning on a different question: are we talking about the sequential or random generation of "[phone] numbers", or are we talking about the sequential or random generation of "[any] numbers"?

chris said,

October 22, 2020 @ 7:29 pm

Surely just as Facebook's proposed definition of an ATDS is too narrow, Duguid's is too broad? Because every single telephone produced in the last 30 years or so "has the capacity to store numbers to be called and to dial such numbers".

This seems like a sound *practical* point, but AFAIK (speaking as a non-lawyer) the mainstream judicial response would be "then the legislature ought to amend the statute". I think it's entirely plausible that the advance of technology has made it the case that millions of people are now carrying equipment that includes the capabilities of an ATDS in their pockets when that was not the case at the time of the Act's passage, but the statutory restrictions on how an ATDS can be used don't actually depend on how common ATDS's are.

As a thought experiment, if some decades-old statute defined a "high-speed motor vehicle" as one capable of exceeding forty miles per hour on level ground, and then placed tighter restrictions on who could own or operate "high-speed" vehicles compared to motor vehicles in general, the fact that nowadays almost *all* motor vehicles would qualify as "high-speed" under that definition might make it urgent to amend the statute, but I expect opinions might vary sharply on the propriety of turning a blind eye to it until then.

P.S. Nearly all computer equipment includes an internal clock, and an electronic clock is a type of sequential number generator, so that brings us back to "using" — if the device doesn't function at all without its clock, does it follow that it is using its clock anytime it is doing anything at all? Clearly I am using my fingers to create this comment, but am I also using my heart and lungs?

AmyW said,

October 22, 2020 @ 8:26 pm

If we're talking about Reed-Kellogg diagrams, I definitely did at least a few in the 1990s in a public school in the US and have a few times been called upon as a tutor to help students with them within the last ten years. So they didn't completely disappear in the mid-twentieth century.

Michael Watts said,

October 23, 2020 @ 1:57 am

Well, the situation is a little worse than you describe. For one thing, you jump to cell phones, but an ordinary handset with speed dial is also equipment that can (1) store telephone numbers to be called, and (2) dial those numbers.

The issue is that if we agree that these are all automatic telephone dialing systems (they meet the definition!), then we must immediately conclude that everyone in the country, for the last couple of decades or so, has been in violation of the law every time they placed a phone call. (They may have dialed manually, but they did it on a device with automatic dialing capability.)

And at that point, Facebook has a strong argument that the law can't be enforced against them, either.

Philip Taylor said,

October 23, 2020 @ 2:16 am

"an ordinary handset with speed dial is also equipment that can (1) store telephone numbers to be called, and (2) dial those numbers" — why is "speed dial" required ? Is there any difference between requiring one push (speed dial) or 9/10/11/whatever pushes ? In both cases, human action is required before the device dials. I would therefore suggest to the Court that the device itself cannot "dial those numbers" and is therefore not covered by the Act.

Michael Watts said,

October 23, 2020 @ 9:55 am

This can't work; the test you propose would exclude everything, leaving the category "automatic telephone dialing systems" empty. Human action is always required before any device dials a telephone number.

You can distinguish speed dial from cell phones by saying that, with speed dial, a human must intervene once for every number dialed, whereas an automatic dialing system as conventionally understood can dial many numbers in a row without requiring human action mid-sequence. But this fails to distinguish cell phones from automatic dialing systems, and so doesn't address the problem at all.

David C. said,

October 23, 2020 @ 10:15 pm

After having skimmed Facebook's and Mr. Duguid's briefs to the Court, I am still at a loss how the texts that were received by Mr. Duguid were generated by equipment that has the capacity of "using a random or sequential number generator". Not knowing the details, I question why Facebook would normally even text or phone random numbers.

I am reminded of the whole controversy around the Second Amendment and the role of the modifier on the main clause.

The reality is that while the legislation was intended to combat robocalls, it is using terminology that is starting to show its age.

Under English law, the golden rule to statutory construction is that a literal interpretation should not be applied if it would lead to a manifest absurdity or to a result that is obnoxious to principles of public policy. This would have parallels with a purposive approach to interpretation under US Law.

U.S.C. §227(b)(1)(A)(iii) prohibits calls by ATDS or a prerecorded voice to, among other things, a cellular telephone service, with the note that it is part of a group of services that would incur a charge for the call.

Interestingly, §227(b)(1)(B) does not prohibit initiating an ATDS call to a residential telephone number, if it did not use an artificial or prerecorded voice. Presumably this is because the caller would be a live person and there would not be an additional charge for the residential phone line.

If we want to be strict about wording, then there's an argument to be made that it wasn't even a "call" that Facebook made, therefore not falling afoul of the prohibition.

Dave Wilton said,

October 25, 2020 @ 1:35 pm

As to whether or not a lexicographer is qualified to weigh in on matters of grammatical analysis, surely the primary value that Garner brings to the table is that he co-authored "Reading Law" with Antonin Scalia, a book that surely all the justices have read. His presence is there to convince Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Roberts that his side is the side of the sainted Scalia. (Presumably Barrett, since she authored a 7th Circuit opinion on exactly this point, will recuse herself.)

And, speaking for myself, I think Garner is well-qualified in terms of subject-matter expertise as well.