Diagrammatic excitement

« previous post | next post »

An interesting Op-Ed in the NYT today by Kitty Burns Florey — "A Picture of Language", about the history of sentence diagramming:

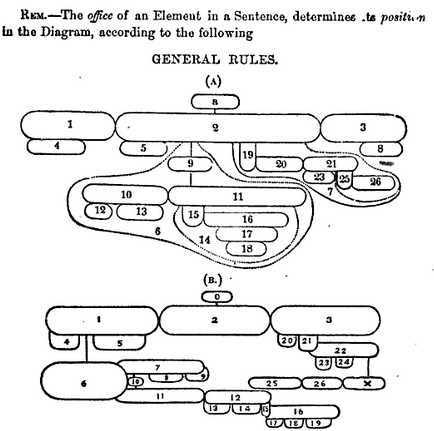

The curious art of diagramming sentences was invented 165 years ago by S.W. Clark, a schoolmaster in Homer, N.Y. His book, published in 1847, was called “A Practical Grammar: In which Words, Phrases, and Sentences Are Classified According to Their Offices and Their Various Relations to One Another.” His goal was to simplify the teaching of English grammar. It was more than 300 pages long, contained information on such things as unipersonal verbs and “rhetorico-grammatical figures,” and provided a long section on Prosody, which he defined as “that part of the Science of Language which treats of utterance.”

The 1863 edition is available here from Google Books. I haven't read it before now, but a quick skim confirms my previous impression that grammar-school children of the 19th century learned more about linguistic analysis than most graduate students in English departments do today. (See e.g. "The child or the savage orator…", 6/1/2004.

Almost eight years ago, Bill Poser and I noted with pleasure an earlier nostalgic essay by Ms. Florey ("Diagramming sentences", 10/11/2004; "Personal and intellectual history of sentence diagramming", 10/12/2004), though I don't think that any of us would go as far as Gertrude Stein, who famously remarked that "I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences".

Elin Edwards said,

March 27, 2012 @ 9:04 am

I agree with Ms. Stein.

I have often commented that diagramming sentences in Mrs. Docken's English class at least partly made up for the fact that my small town high school didn't offer fine arts classes.

Victor Mair said,

March 27, 2012 @ 9:22 am

I remember fondly diagramming sentences in junior high school and high school. It was probably the most fun that I had in my public school education. It was always a challenge, especially with complicated sentences, to make everything fit in a logical fashion, where everything had to be accounted for by a particular grammatical rule.

dw said,

March 27, 2012 @ 9:32 am

Interesting.

Being educated (up through college) in England, I'd never heard of diagramming sentences before I came to the US. It's still something of a mystery to me.

Coby Lubliner said,

March 27, 2012 @ 9:40 am

One thing I found interesting in Clark's book is the assertion that "Grammar is the science of Language." It means that as late as the mid-19th century 'grammar' had a far broader sense than it does to modern linguists, some of whom get quite bothered when non-linguists use it the old-fashioned way.

blahedo said,

March 27, 2012 @ 9:40 am

Most people under about 40 or so haven't heard of it even here. I was coming up through primary school in the 80s and I think when I learned sentence diagramming it was already mostly the domain of parochial (private) schools.

Mark Dunan said,

March 27, 2012 @ 9:52 am

I agree, Blahedo. I went to elementary school in the '80s too, and never saw a diagram until linguistics in college. And the tree-like diagrams of Linguistics 101 don't much resemble the one in the NYT article.

mike said,

March 27, 2012 @ 10:59 am

In case it's not evident, Florey has a book out about diagramming — "Sister Bernadette's Barking Dog: The Quirky History and Lost Art of Diagramming Sentences." It's good fun.

Linda said,

March 27, 2012 @ 11:05 am

I attended a girl's grammar school in England during the 60s. We were taught diagramming in English lessons in the IIIrd Form (what is now Year 7, age 11-12)

Arika Okrent said,

March 27, 2012 @ 11:33 am

Measuring emotional response to sentence diagramming tasks in children would be a good diagnostic tool for identifying future linguists. This would be followed up by a test for whether conjugation/declension tables give the warm fuzzies or the chills. We could get them younger and increase our tribe! I didn't discover linguistics until after college. When it was so clear all along!

Philip said,

March 27, 2012 @ 11:49 am

I graduated from a public high school in California in 1965 and spent lots of time diagramming sentences–but mostly in middle school. Dunno how much I "learned," though.

Chomsky's famous pair of sentences–John is easy to please/John is eager to please–would be diagrammed identically, even though John is the object in one and the actor in the other.

If diagramming sentences doesn't show the grammatical relationships between the deep structure constituents in a sentence, then what's the point?

Bill Benzon said,

March 27, 2012 @ 1:06 pm

I too enjoyed diagramming sentences, in the 6th grade I believe. I thought of it as a species of puzzle-solving and I’d like to believe that the act of creating a visual representation of sentence structure was intellectually useful in some deep way, as though learning to go back and forth between visual and propositional modes of thought created a useful matrix in which later thinkng could take shape.

Alas, I fear Mark is right about English graduate students. Linguistic analysis isn't part of the training and probably hasn't been since the days when graduate study and research in English was organized around philology. That ground to a halt probably during the 1950s.

Michele Benyo said,

March 27, 2012 @ 3:51 pm

I, too, loved diagramming sentences and love grammar to this day! Like Victor, I enjoyed the challenge of complicated sentences, and, like Bill, I thought of it as puzzle-solving. To me grammar is the most delightful of puzzles!

Bill Walderman said,

March 27, 2012 @ 5:04 pm

"If diagramming sentences doesn't show the grammatical relationships between the deep structure constituents in a sentence, then what's the point?"

With that criterion, wouldn't any kind of grammatical analysis prior to 1957 be pointless? Diagramming may have reflected a more rudimentary grammatical analysis than present-day syntax, but it got students thinking about the structure of language, and, I think, helped many students become better writers. And, who knows? Maybe Chomsky himself started thinking about these things as a result of diagramming exercises in primary school.

Ellen K. said,

March 27, 2012 @ 6:05 pm

@Coby Lubliner:

The current broad use of "grammar" is not the same as grammar as "the science of language". People call spelling errors grammar errors. Science has nothing to do with that. Or are you are also proposing some alternative meaning of "science"?

Carl Offner said,

March 27, 2012 @ 9:36 pm

I wasn't bad at writing in junior high school, although of course I'm much better now. And I remember diagramming sentences. I found it easy, and I liked it. I have never done it since. A year or so ago, for some reason I tried to do it again. I failed completely. Of course I know what noun phrases and verb phrases are, and so on, at least in a non-technical sense. But I can't for the life of me diagram a sentence.

And yet in some sense, I think that diagramming sentences in junior high school served me well. I'm guessing that I probably write more coherently (well, at least at the level of sentence structure) because of it. But is this really true?

Bobbie said,

March 27, 2012 @ 10:27 pm

I can no longer diagram a sentence, but the lessons stuck with me forever. Because of Miss Foster, my 7th grade English teacher, I will NEVER use an incorrect pronoun as the object of the prepositional phrase! And I cringe when anyone else says "Between she and I".

Bobbie said,

March 27, 2012 @ 10:27 pm

I can no longer diagram a sentence, but the lessons stuck with me forever. Because of Miss Foster, my 7th grade English teacher, I will NEVER use an incorrect pronoun as the object of the prepositional phrase! And I cringe when anyone else says "Between she and I".

Chad Nilep said,

March 27, 2012 @ 10:40 pm

@Philip

"Chomsky's famous pair of sentences–John is easy to please/John is eager to please–would be diagrammed identically, even though John is the object in one and the actor in the other."

Interesting labels. In terms of overt syntax, both tokens of 'John' are subjects; in terms of information structure both might be called topics.

Discussions of the semantics of the pair often note that the first can be paraphrased to make 'John' the syntactic object ("It is easy to please John"). But using the terms 'object' versus 'actor' to describe the original sentences with identical surface order points out the ambiguity of those terms, which get used differently in different linguistic approaches. (I don't think either would be called an actor in terms of thematic role, but treatment and terminology may vary.)

Which, @Coby Lubliner, I suppose suggests why some scholars become very protective of their preferred terminology, even if it disagrees with popular usage or other scholars.

Dominik Lukeš said,

March 28, 2012 @ 2:56 am

I (and generations of Czechs) was taught a home-grown version of diagramming developed by a functionalist linguist. We mostly hated it and I doubt we learned all that much about language. I became a linguist despite it not because of it. But I do remember finding all the fuss about constituent analysis and even Chomsky's trees a bit puzzling. It seemed trivial (but I still had to learn it from scratch).

Andrew Dalke said,

March 28, 2012 @ 6:13 am

We learned sentence diagramming in Miami in 8th grade, so that would be 1983/4. The teacher loved the concept, and she talked about an ex-student who after becoming a lawyer came back to tell her that sentence diagrams really helped her understand some of the complicated sentences she was reading.

I, on the other hand, could make no sense of the rules. It didn't help that the first sentence of a test was "Have you ever seen a pilot fish?" The rest of the sentences were about pilot fish and sharks, but as my uncle, the United Airlines pilot, also fishes, I diagrammed a rather different structure than the teacher expected, and I thought they were just random sentences.

This was the same teacher who had us memorize (incomplete) lists of prepositions, conjunctions, and other parts of speech. "Aboard, about, above, across, after, against, along, among, around, at, …"

Coby Lubliner said,

March 28, 2012 @ 11:07 am

Ellen K.:

I daresay "science" was used more broadly in the 19th century than today — witness "Christian Science" etc.

As regards spelling being a part of grammar: Nebrija's Gramática de la lengua castellana, the first grammar of a living language, has Ortografía as one of its divisions.

peterv said,

March 28, 2012 @ 11:22 am

No doubt some of the pleasure (to those who enjoyed it) or pain (to those who did not) of this activity came from the use of both hemispheres of the brain. Ditto with the teaching of Euclidean geometry. How rarely do those of us with dominant visual hemispheres get to express ourselves under the text-hegemony of contemporary western education.

Philip said,

March 28, 2012 @ 11:45 am

@Chad: The labels (actor vs. agent) aren't particularly important. The point I was trying to make is that diagramming sentences shows only surface structure, not deep structure, relationships. "John is easy to please" and "John is eager to please" would be diagrammed identically, even though native speakers of English immediately recognize that in the first sentence John is being pleased, and in the second John is doing the pleasing.

Native speakers also recognize ambiguity–sentences with identical surface structures, but different deep structures. Ambiguous sentences ("Visiting relatives is boring" or "It's too hot to eat") are also diagrammed identically.

And, sure, diagramming sentences is useful in that students are identifying (and learning to manipulate) the constituent elements of English sentences. But spending hours and hours learning what native speakers already know (what the constituent elements of a sentence are) is counter-productive (at least in my opinion) because that time would be better spent doing something much more useful–like actual reading and writing.

I'm almost certainly singing to the choir here, but native speakers already know the grammar of their language. That's what "native speaker" means. A formal knowledge of syntax is not a precondition to being a good writer. Native speakers of English who are poor writers struggle in composition classes not because they don't know English grammar, but because they don't read much and they haven't spent much time writing.

So why spend time diagramming sentences?

Ken Brown said,

March 28, 2012 @ 12:26 pm

What Philip just said. If you needed to be taught this stuff to write well, then no English-educated writers would be any good (apart from the few that studied linguistics or philology post-school, or who spent some time in secondary schooling in the USA) because over here we very rarely study any sentence diagramming at school, and never did much.

But obviously many English writers are quite good at making up sentences. You don't need to learn formal descriptions of grammar and syntax in school to be able to do them properly in real life.

In fact that's the amazing thing about it. Most averagely competent first-language English speakers – and I assume the same is true for speakers of any other natural language – already know most of the rules for producing standard English sentences by the age of about 4 or 5. Long before school has had any significant input. They pick up most of the rest while still chidren, while at primary school – and if they get it from school they must absorb it by example from the teachers, the other kids, and reading material, because there is little formal teaching about English grammar at that age (there wasn't even when I went to school in the early 60s). By the time they get to secondary school and are exposed to descriptions of language such as subjects and objects and possessives (as we were taught to call them in English lessons when I was 12) and are taught to break sentences into phrases and clauses, they already know how to produce more or less arbitrarily complex English sentences, even using words they have never encountered before. And even if they can't analyse a sentence in any formal way they know what some utterances "feel" right and others don't – they can, I am sure, tell fluent native speech from non-standard or un-natural English.

That's pretty wonderful when you think about it.

Alex said,

March 28, 2012 @ 5:38 pm

When I did my undergraduate at Northwestern, I took "Formal Analysis of Words and Sentences" to fulfill half my distibution requirement in "formal studies." It dealt with phrase structure, diagramming, and phonetics. Every other class under "formal studies" was math, logic, or computer science.

That class was a lot of fun, especially the little puzzles where you were given sentences in an unfamiliar language and their translations, then asked to figure out how to make a new, grammatical sentence in that language. Until that class in college, I'd never had explicit instruction in the structure of my own language beyond categorizing words as parts of speech. In high school, I learned more about grammar from Spanish class than I ever did in English. I wonder why, since it used to be a standard part of English instruction. Maybe they just don't have enough K-12 teachers who can analyze English sentences?

Those skills have been useful to me in learning new languages, and in figuring out aspects of English that don't come intuitively to me. Figuring out where "who" or "whom" would be correct in formal English is a lot easier when you can reliably break down subordinate clauses.

Philip said,

March 28, 2012 @ 6:12 pm

@Alex: "I learned more about grammar from Spanish class than I ever did in English" is a pretty common experience.

It's because the formal study of English syntax got off to a terrible start. When people started writing the first English grammar books in the 17th century, they assumed that because Latin had a certain structure, English must, too. But English is a Germanic language, not a Latinate (aka Romance) language. Using the syntax of Latin as a model for English syntax is like forcing a square peg into a round hole.

When people begin to study Spanish or French in school, many of the things that didn't make sense when they studied English grammar, suddenly do–because Spanish and French are Latinate languages.

svanduym said,

March 28, 2012 @ 7:13 pm

Believe it or not, I diagrammed sentences in 7th grade in 1995 at a Louisiana public school. It was a "gifted" class with a very odd teacher, though.

dporpentine said,

March 29, 2012 @ 6:18 am

Just to pick up the "graduate students in English are amazingly ignorant of substantive ways of analyzing the grammar of the language they ostensibly study" theme: it should be noted that many graduate students in English go on to become English professors. Thus the frightening ignorance of so many English professors, and their receptiveness to nonsense theories that involve nonsense claims about All Language.

The one caveat is that there is, in general, a direct relationship between how much English professors know about language and the historical period they study. So people studying postmodern stuff *tend* to know the least and medievalists the most.

Philip said,

March 30, 2012 @ 12:29 pm

Dunno about postmodernists vs. medievalists, but, for sure, a degree in English means someone has studied the history of British and American literature. But the job an English major gets you usually involves teaching composition courses. There's absolutely no fit, no connection, between the job requirements and the background one needs to get the job in the first place.

I'd certainly agree that English teachers are as receptive to nonsense theories and nonsensens claims about language as anyone else.

Bill Benzon said,

March 30, 2012 @ 6:25 pm

Well, a medievalist is going to have to learn some old varieties of English, Latin for sure, and who knows what else, depending on specialization. So they're likely to spend more time with the nuts and bolts of language that anyone who specializes after the early modern period.

AJ Wilkinson said,

March 31, 2012 @ 4:06 pm

I remember diagramming sentences in the 6th and 7th grades (would have been about 1963-1965 or so), and remember asking myself–and the teachers, and my parents–what was the point? I already knew how to write and talk correctly–why did I have to diagram, or more pointedly memorize terms for sentence structure that I already knew instinctively? The only thing I can substantively remember from that is a cute definition of what a preposition is ("anyplace a little bug can go"–think about it). My ability to construct a sentence was not advanced by that knowledge, however, any more than the bug's.

Tom Hughes said,

March 31, 2012 @ 8:17 pm

I agree with A.J. I retired as a high school English teacher in 1996. A fellow English teacher who retired with me was the last of the diehard diagrammers. As a student I loved to diagaram, enjoying the challenge of more difficult sentences. I now wonder what the purpose was. It did not make me a better writer. In retrospect, I find it to have been largely a waste of time. (I hope that my fellow retiree doesn't see this; if so, I'll be sure to be chastised).

Tenney Naumer said,

April 1, 2012 @ 12:39 pm

I lived in Brazil for 14 years, and sometimes made a living as an English teacher.

Having diagrammed sentences in grade school was an enormous help in teaching the advanced students to write in English. And understanding that a sentence in English can be broken up into phrases was very important in teaching the up-and-down "flow" of speaking an English sentence, with tiny pauses between the phrases.

I don't know if I would have been able to do this if I had not diagrammed sentences in grade school.

Diagramming is one of the few activities I remember from grade school English.